There’s a village in the Czech Republic called Loděnice, a 30-minute drive southwest of Prague. With a population of around 2,300 it might not get pinned on many tourists’ maps, but it is the home of a global powerhouse. Since it began production in 1951 as a state-owned company called Gramofonove Zavody Loděnice, supplying vinyl records and record players to neighbouring Soviet bloc nations, GZ Media has gradually become the world’s biggest manufacturer of vinyl records.

It’s had the same CEO for 32 years, Zdenek Pelc. He’s "the longest running CEO in the history of the Czech Republic", he tells me proudly (the Republic itself is only 46 years old) and with a payroll of around 2,000, the company he runs is nearly as populated as Loděnice itself. But the scope of GZ Media goes beyond the village. As well as a decades-long business in CD and DVD manufacturing (known in the industry as "replication"), and more recent branded packaging contracts with BlackBerry and Ikea, this pressing plant is working to come out – and stay – on top in what’s become a much-debated resurgence in vinyl sales.

Since much of digital music technology is helmed by a crop of multi-billion dollar companies, with millennial branding and self-styled demi-gods for CEOs, you’d be forgiven for thinking that the marketing strategies and modes of consumption for a medium like vinyl are concerns for a comparatively sluggish underground; a physical product that’s barely changed for generations, yet discussed on panels, in clubs, in record shops, on loop. The companies who supply them, too, must be similarly small-time affairs.

But the year-on-year growth of the market recently has been remarkable. The Official Chart Co. noted that 2014 was the first year since 1996 in which sales in the UK reached the one million mark and, according to Nielsen Music, sales in the US alone increased 52% on the year previous to hit an impressive 9.2 million in 2014. And just this past week, the Official Chart Co. also launched the weekly Official Vinyl Albums Chart and Official Vinyl Singles Chart, for the first time in the company’s history.

Such increases have sparked a variety of conversations, many of which fork out from issues surrounding Record Store Day; backlogs at pressing plants in the US, western Europe and the UK, often stalling independent label operations; the re-pressing of "classic" LPs as high price-point, special edition releases, creating a pseudo-luxury market that reinforces a stereotype of dad-rock collectors grasping onto the past; right down to the Discogs-dwelling multitudes who rip off artists, labels and buyers. But a simpler question seems to have passed by: who is actually making these millions of records? Since 13.7 million of them emerged from GZ Media’s plant in 2014 alone, it would appear that this company is a key player in the story.

After the drive into Loděnice, we’re ushered into GZ Media’s reception area, with wood-clad walls, cork noticeboards and entrance turnstiles. Walking through the narrow corridors and into the main hub of the plant, the sound, smell and heat of the machinery linger. There are around a dozen presses in action inside one large concrete room, the walls lined with metal containers holding thick paper bags of coloured dye fragments, spiral-hardened wax leftovers, copper-plated master discs and boxes of insert labels. The familiar graphics of The Rolling Stones, Black Sabbath, U2, The Sex Pistols and Disney’s runaway success story Frozen are plastered across the walls in intervals; visual references to the bleeding of the underground into the mass market.

The dozen or so workers on this daytime shift are mostly women. They wear sandals or light trainers, and a combination of cotton vest and shorts, or loose cotton dresses. The heat is cloying and when mixed with the faint chemical smell and thudding of pressing metal, the combination feels woolly. In a 12-hour day or night shift, each worker gets two thirty-minute breaks. Those manning the presses alternate between full-time and part-time working weeks each month – three to five days on some weeks, two to three days on others.

When asked how much they are paid, CEO Pelc shuffles in his seat slightly. It’s somewhere between 27,000 and 40,000 koruna per month, approximately £728 and £1078, which he quickly adds is more than the current national average. (For manufacturing work in the Czech Republic, the monthly wage between 2000 and 2014 averaged at around 24,989 koruna.) He adds that they "don’t have very much education – only an elementary one – and so we give them work. Here, in the Czech Republic, people are still willing to work."

What do you mean by that? "Well, we don’t have the problems that come with western Europe, like in France, or Switzerland. We can ask people to work Saturday and Sunday nights, and they will. I’m not sure they’re too happy to do it," he adds with a short laugh, "but there is a necessity to meet demand and we pay them well." The remark about the workers’ education is also an almost word-for-word echo of that of our guide earlier that day. Why the disparity between wages, if each worker operates the same presses for similar hours? It’s down to individual productivity, Pelc says. The more records they press in each shift, the more money they take home at the end of the month.

After the record number of 13.7 million pressed last year, he estimates that the employees of GZ Media will press "around 20 million" by the end of 2015, "- a huge increase, yes, but we can do it." GZ Media’s aim could well be realised: because of the demand in vinyl-buying habits in western Europe, the US and Japan, where regional pressing plants find themselves with regular and lengthy backlogs, the scarcity of the presses themselves is something GZ Media are trying to build a monopoly on.

"There are no manufacturers for new, mass-producing, vinyl-pressing technology anywhere, so this shortage means that we’ve developed our own presses and galvanics." These planned twelve new presses operate in much the same way as the older models, and the galvanic process employed is not dissimilar to that of other plants, either. (Through the process of direct metal mastering, copper-plated master discs are placed into a galvanic bath until plated with a layer of nickel, which is then peeled off and used to stamp the discs inside the presses.)

This investment is about renewal. They don’t intend to replace the still functioning, older presses, but to add to the growing arsenal of a technology they refused to retire decades ago. This has given them a comparatively serious advantage, and their operations schedule won’t be much of an obstacle, either: the plant is open 24 hours a day, seven days a week, 360 days per year.

Corporate talk aside, however, the plant doesn’t feel primed to accommodate such an expansion. There are large, unlit rooms, with doors open or removed, stuffed with abandoned, dust-covered machinery. Peeling stickers on pipes are dated from the late 1980s and early 1990s. It’s less apparent what these machines were for and why they’re no longer used, considering that the far older presses are almost never turned off. The contrast in what is and is not a useful machine appears uneven.

"We already have two of the new presses running," boasts Pelc, referring to a pair of large, blue-painted presses that sit at the head of the main room, far larger than the older, green-painted presses – "and by this April, we’ll have ten more. This is all of our own construction and production, with two companies in Czech Republic and Thailand supplying us directly. No other plant in the world has these machines – or any other new machines." Pelc says that while current US and western European pressing plants typically have an order turnaround rate of about "four to five months", GZ Media boasts a turnaround of "four to five weeks".

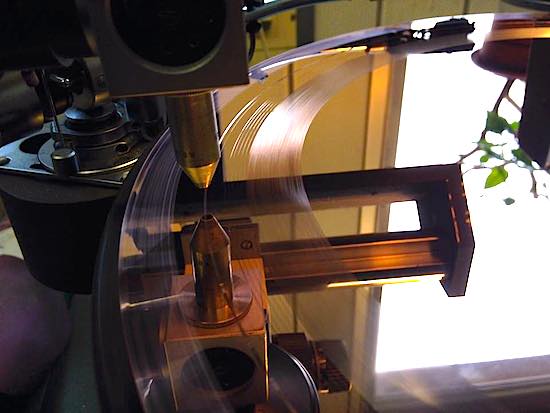

Although the loaded schedule is reinforced, vinyl pressing is not intended to become a quick-buck "replication", like the CD and DVD boom years. There’s still an artful process in play. After clients send in digital files of recordings to the in-house acoustics labs, the engineers cut each record to the copper-plated master discs with a diamond-tipped needle in real time. The effect of watching the grooves of an LP being cut as the music is played out in the lab, with low-level chatter from the engineers about how it’s sounding, lends itself to the labour-intensive mechanics of a format they refused to abandon – even when there was money to be made elsewhere.

"I noticed around 2001 and 2002 that the replication business was going to stop growing," insists Pelc. "Now, if you look at the current EU market, many of those who stuck mostly with [CD] replication are either in bankruptcy, or close to it. We’re the only replication company I know of that’s actually growing." Could this recent upsurge in vinyl consumption match up to the late 90s new technology boom, then? "No, it definitely won’t. At our peak, before the 2000s, we were replicating 150 million CDs and DVDs per year. We’ll be lucky in a few years time to be pressing 30 million vinyl. It’s not going to become a replacement for digital discs, but… some people just like their music to be touchable."

He notes that higher price-point, special edition vinyl products for major labels are big business: one Rolling Stones item, two large boxes of 33 individually-numbered LPs, were designed, pressed and sold directly to Rolling Stones fans clubs worldwide. "Vinyl is not just a product," he notes. "It’s a hobby, and people are willing to pay for it."

Taking the packaging side into account, 2014 saw vinyl become one third of GZ Media’s revenue, and around 25% of their 2.1 billion koruna – approximately £56.4 million – profit. That’s a lot of special edition LPs for Record Store Day, pressed 24 hours a day in a Czech village.

Back in London, and with the hype and criticism of Record Store Day building once again, the next step to bring records from pressing plant to record store is by the distributors and manufacturers. Keyproduction is one of the longest running and largest of its kind in the capital, specialising in CD and DVD replication and, importantly, vinyl and vinyl packaging manufacture. With the sound of the presses in mind, I asked, how have you seen the vinyl industry change in recent years? "We have been manufacturing vinyl for 25 years, and have always had a demand for it," insists Karen Emanuel, managing director and owner of Keyproduction.

"The demand slowed over time, because many factories closed. Over the past few years it has increased again, but without the same capacities to press records. The plants aren’t as flexible, and can dictate terms much more now than in the past. We work with four pressing plants on a regular basis, and it takes three to four months to turn around a release rather than the three to four weeks that it did in the past. We have to pre-book capacity and schedule very carefully in order to fulfil our clients’ requirements."

So, there is a definite issue of a lack of pressing plants, in creating these backlogs? "To give the plants their due, though, they have to schedule a lot of work and they don’t pick and choose the higher price-point releases," says Emanuel. "They have to work very closely with their clients (i.e. companies like us) to schedule ahead, and so on. I know I would say this, but it is often better for a record label to put their work through us, rather than go directly to a plant, as we will have planned ahead in terms of securing capacity."

Is it the case that the industry has made a concerted PR push to make vinyl a more mainstream medium? Or are companies, like your own, tapping into a more wide-reaching cultural shift towards vinyl as a fashionable product? "From our perspective, we work a lot with the independent sector of the industry who have always supported vinyl. I have definitely seen a cultural shift, though. Not that long ago, younger fans didn’t know what vinyl was. Now, they are all clamouring for it, and with sales of record players increasing."

Now, the elephant in the room: Record Story Day. How has the growth of the Record Store Day ‘project’, as it were, affected your work? "It has grown very quickly to be an important day in the calendar," Emanuel explains. "It does come with its problems, though, as we are trying to fulfil so many orders all for the same delivery date." So RSD does have a direct effect on labels? "There are pluses and minuses to the RSD project. The idea behind it is great, and it has bought peoples’ attention to independent record stores. The day itself is a lot of fun, and we’re really proud to have worked on some amazing pieces of product, but I’d say some of the criticisms are valid."

How do the demands of Record Store Day affect your day-to-day work, though? "Turnaround times do extend around this time of year, so we advise starting releases very early to ensure a timely delivery. We do try to pre-plan with our clients as much as possible to make it painless, but more complicated releases naturally take even longer. We might have to source particular items for inclusion in the product, and that adds time to order in special materials, time to send the finished product out for signing, and so on. Overall, though, I’d say that the recent surge in vinyl is not just for Record Store Day."

This week, independent labels and record stories across London are preparing for another Record Store Day. Some are booking all-day line-ups of DJs and stocking the shelves with exclusives, while others actively shun it: YAM Records in Peckham is forgoing the runs of exclusives for a concerted focus on independent South London labels, and experimental grime label Local Action have posted a FCKRSD promo code, for half-price vinyl. Record Store Day is becoming a more contentious issue throughout the industry – from factory workers and CEOs, to label owners and record buyers – but it’s also the easy face to pin on the dartboard of a wider, more nuanced and more interesting discussion about the growing popularity of vinyl; as a product, medium and lifestyle token. Take it as glib or sincerely as you like, but what Pelc said back in the Loděnice factory remains true: "Some people just like their music to be touchable."