Vinyl racks at The Book And Record Bar

In 2013 I ran a successful crowdfunder to finance my band, Metamono’s debut album With The Compliments Of Nuclear Physics. All the members shared a strict aesthetic and environmental policy: all the sound had to be analogue and all the gear we recorded on recycled or handmade. Our first releases were cassette only, followed by a couple of 10” singles and for the album we planned a double on 180g vinyl in a gatefold sleeve. There was never any question that vinyl conformed with our values and even somehow demonstrated them. A classic product oozing the patina of yesteryear: vintage, up-cycled, analogue, DJ friendly.

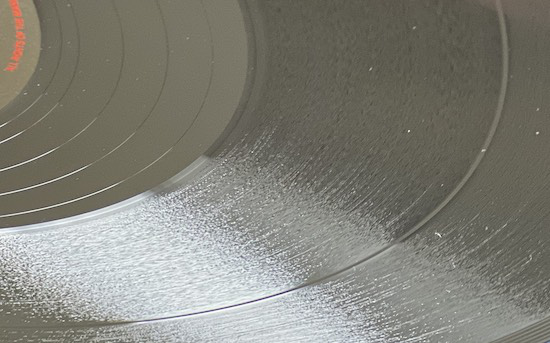

Once the cash was in from Kickstarter we ordered our vinyl, which was to be shipped from Holland. UK was still in the EU and the pressing plants were still accessible to independent labels with a prompt turnaround. An eagerly anticipated pallet arrived in Crystal Palace – but there was a problem. Clearly under time pressure, the freshly pressed vinyl had been put into the polythene bags still warm, producing catastrophic surface noise on every single one. 600 copies of a double album, 1200 discs, were useless. The manufacturer, bless them, took responsibility for their mistake and simply replaced the order; in a few weeks another 1200 12” 180 g slabs of vinyl arrived. To this day the unplayable ones languish in boxes stashed in the sheds, garages and building cavities of the band. That’s a lot of waste plastic, yet the implications didn’t quite dawn on us.

It was such a given that vinyl was virtuous, that even for the eco-conscious recyclers of SE19 the glamour had created a massive blind spot. The format itself was so beloved that it transcended the humdrum worldly considerations that would lead us to worry about putting our milk cartons in the correct bin, or revarnish a battered old table rather than nip to Ikea, or argue over whether a patch cable was recycled or not, all whilst enthusiastically having 432 kg of PVC shipped to our door. Nevertheless, to quote Paul Conboy from the band: “Our way was greener than most. Pre-sales to fans, sleeve locally printed. The damaged copies were unfortunate and there should have been some way to recycle them. It all pales though when you think how much Adele and Ed Sheeran will end up in landfill this year.”

Nine years on and for many music lovers, collectors and artists the blind spot of their addiction to plastic persists, but some are waking up to the materiality of the music business. The environmental cost of how we enjoy music, whether as a stream, download, CD or vinyl is beginning to be reckoned and slowly tackled.

Vinyl is made from the plastic Polyvinyl Chloride (PVC), which hails back to the early days of plastics. It’s a direct product of crude oil sourced largely from autocratic regimes in the Middle East. In its pure form PVC becomes unstable and produces the highly toxic gas hydrogen chloride when heated, so to be used to press records it needs to be mixed with other compounds to keep it stable. Although now being phased out these stabilisers have traditionally been either lead or cadmium, both extremely poisonous and harmful to the environment.

The PVC that goes in to records has to be of near perfect consistency to avoid unwanted surface noise, warping or instability. Any decrease in quality is immediately audible. Incidentally another additive to vinyl for records is carbon which not only makes the vinyl black, but acts as a conductor to reduce the static charge that builds up in the PVC attracting dust, which increases the wear on vinyl while playing.

Kyle Devine’s excellent and meticulously researched book Decomposed: The Political Ecology Of Music is packed with sobering facts concerning all formats from shellac through to streaming. Vinyl does not come off lightly. The book begins with a trip to Thailand to visit TPC, a sprawling petrochemical plant that produces 500 kilos per hour of the high-grade PVC granulate that records are made from.

“The polymerisation of polyvinyl chloride uses carcinogenic chemicals that can harm its handlers, while the operation produces toxic wastewater that the company has been known to pour into the Chao Phraya river… [Map Ta Phut, the area around the plant] is one of Thailand’s most toxic hot spots with pollution-related health impacts including cancer and birth deformities.”

The economic impact of World War Two drove manufacturers to look for an alternative to shellac, a format which has its own social and environmental issues. A number of vinyl resins had existed since the late 1920s “yet it wasn’t until after 1948, when Colombia Records introduced the long-playing record that the recording industry began to fully embrace – and propel – the plastic age”. PVC had endless applications from flooring to pipes to toys, but the exacting standards required to deliver high quality audio was a major driver in R&D: “Music is not simply a passive observer of the plastic age. It is an active contributor to petrocapitalism, an agent of petroculture.”

Records are not, sadly, immortal. Of the billions of vinyl records that have been pressed since the 1950s, the vast majority, despite the second hand market, will be sent to landfills where they disintegrate releasing their lead, cadmium and other toxic and carcinogenic chemicals into the ground. Others are sent to incinerators, where they become toxic smoke laced with hydrogen chloride. To give an idea of the scale of the issue: “At the height of worldwide sales — nearly a billion units worldwide in 1978 alone – the amount of PVC used to manufacture LPs weighed in at about 160 million kilograms.”

If we want to avert the climate crisis and leave a carcinogen free world for future generations, the question is whether we abandon vinyl entirely (heartbreaking and unconscionable for many) or make it clean and sustainable. Thankfully, there are a growing number of people who are attempting to do just that.

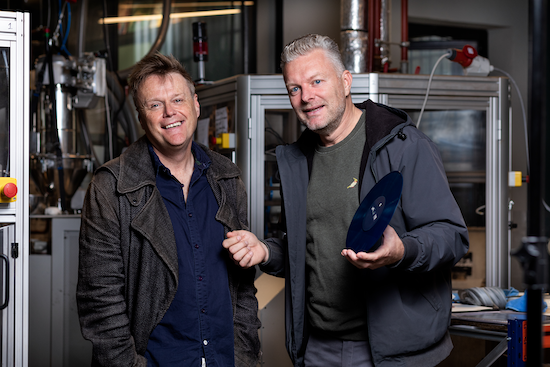

Rachel Lowe and Simon Parker of Naked Record Club

One such initiative is the Naked Record Club, a curated, vinyl-only subscription service due to be launched in June releasing a mix of re-issues and new acts on a monthly basis, all, they claim, on eco-friendly vinyl. Owners Rachel Lowe and Simon Parker, who ran the Vinyl Revolution record shops, told me: “When we started this we honestly didn’t know if it was possible to make records that were non-toxic and recyclable. We thought there’s got to be somebody out there doing something that’s better than the vinyl records we’ve been selling. We did some research and found DeepGrooves and started working with them. It was a pretty simple process but other people don’t seem to be asking the question. The awareness is so low.

”It’s quite funny really, Vinyl Revolution was a music store with other merchandise. All our clothing, our art, everything else we did, we sourced it all organic, ethnically, sustainably — we got abuse from customers for not providing plastic bags! We did all of this but by a million miles the biggest product we were selling was vinyl records.”

According to the DeepGrooves website they are “Europe’s greenest pressing plant” set up in 2017 by Chris Roorda. I asked Sales manger Ruben Planting, who has worked with Chris for eight years, how they manufacture sustainable records: “We use a very clean PVC. We do chemical testing with the University-based plastic scientists and they’ve established it’s the purest form there currently is.” Significantly, the PVC granulate that they heat up to make the records contains no heavy metals, but is based upon non-toxic calcium zinc stabilisers.

“We can recycle any left over excess or mis-presses back into our system. Some people think we recycle old records from the 70s, but because they are made from completely different types of material you can’t mix them. If you did it could clog up the machines or you’d get loads of clicks and crackles on the record… Therefore we recycle internally, but backstock and goods that we can’t recycle are being used for other PVC products. At the moment we ship to a company that are making drainpipes out of it, or other types of piping in new buildings.”

“We’re not making purely eco-products – we still use plastic and paper which makes a record – we’re just trying to be a green as possible with every step that we’re taking.”

Simon Parker and Chris Roorda at the DeepGrooves plant

With awareness of the toxicity of vinyl so low, I asked Ruben when he decided to change to green vinyl: “We didn’t change at all, it’s something we already did from the start! Right from 2017 we found it completely normal for whatever we were doing to have the backdrop of sustainability for the future. Without even telling our clients, all our packaging is FSC certified, the suppliers close nearby, the energy for the factory was already from solar panels on the roof and bio-mass. It wasn’t until the start of 2018 that clients told us that we were the only ones doing this, so we thought maybe we should make a statement. After that the bigger, older plants began to follow as well. I think now, for example [German manufacturer] Optimal is growing its own forest. It’s a huge compliment. Of course it’s not entirely due to us, but we are being watched and it’s something the industry needs to be doing.“

Tantalisingly, the search for an alternative for PVC is on, although shrouded in secrecy. The effect on audio quality is yet to be tested, new machinery needs to be developed and plants will need to be rebuilt again from the ground up, but it’s on the horizon.

So it seems records, despite their origins in crude oil, can be non-toxic and carbon neutral. Yet how can it possibly compare to streaming, the leading music format which has none of the physical issues that companies like DeepGrooves are wrestling with? The answer is: very favourably. The infrastructure needed to create the illusion of immateriality in “The Cloud” is vast and very, very hungry for energy and raw materials. At the consumer end we simply don’t see the enormous server farms (aka data centres), vast network of undersea and underground cables, millions of miles of PVC insulated copper, and power-guzzling air-conditioning.

One-to-one comparisons between formats can be misleading but can give us an idea: “Listening to an album via a streaming platform for just five hours is equal in terms of carbon to the plastic of a physical CD. The comparative time for a vinyl record is 17 hours.”

One of the reasons this can be misleading is due to the Jevons paradox which states that, “in the long term, an increase in efficiency in resource use will generate an increase in resource consumption rather than a decrease”. Streaming has made music consumption efficient and accessible to the point that it has pushed consumption to an unsustainable level, a level that would not be reached if it didn’t exist.

Simon Parker with DeepGrooves lead-free vinyl granulate

Whatever the comparison to other formats, the scale of the energy usage, and therefore carbon emissions, by the data centres that provide our streaming services is so great that it has an impact at a national level. Ireland, for example, opened up to data centres in 2000, but now, after suffering “brown-outs” due to the power demands of the servers, a bill intended “to restrict certain developments in fossil fuels infrastructure and high energy usage data centres …to ensure that regard be given to the State’s climate targets and commitments” is currently before Dáil Éireann, the Irish parliament. In short, the server farms are so hungry they’ve caused national energy insecurity, jeopardising Ireland’s Paris agreement commitments.

Music is a very different online product to many others. Unlike other media, the listener is encouraged to repeat the stream endlessly, deepening their enjoyment with each play. The result is that carbon emissions spiral out of control. Plus, as Ruben points out: “Even if you don’t stream the music it’s still on that server and it needs electricity to be available. If you have a record you don’t need any energy in order to just store it in your shelves. In my opinion, over a lifespan streaming is much more harmful and has more of an impact than the vinyl industry.”

So if we recoil from streaming and return wholeheartedly to vinyl, what’s the cost of going green?

Michael Johnson is the proprietor of South London’s excellent Book And Record Bar dealing with both new and second hand vinyl, so knows the market at the retail end. What’s the cost to the consumer of green vinyl?

“It’s not something that’s ever promoted! You never see on a press release or something from a distributor, saying this is green vinyl, this is a green as it gets, this is recycled from xyz – I’ve never seen that.”

Curious. So what’s the price of new vinyl anyway?

“Well, that’s the trouble. It goes all over the place. If you get a small independent label in the UK, for example Trunk or Castles In Space, their charge to me as a retailer is in the region of a tenner for an album. But if I’m getting something like Light In The Attic sent over from the States via a distributor here that could be over £20. So a massive difference from our point of view. Japanese labels have been reissuing ambient stuff and they are coming in at £28. I have to sell it at £36 to make any profit. And of course at lot of them are going 180g and 220g vinyl so they are actually using more PVC than was traditionally used in the 70s, 80s and 90s. But it is the majors who are pushing up the prices. Warners took over the Bowie catalogue and put the price of his albums up by over £20 retail. There’s no incentive for them to go green, they are not investing in new plants just maxing out the independent ones.”

As any audiophile should know, there is zero advantage to making a record any heavier than 140g. In fact the heavier they are the greater shipping costs and the more likely they are to damage their own packaging. It’s a snobbery that has developed out of some records being manufactured too thinly to save resources during the oil crises of the 70s.

The majors new commitment to vinyl continues: recent albums by ABBA, Elton John, Adele and Ed Sheeran alone add up to millions of new vinyl pressings. The impact of this on the independent record companies – the very labels who have kept the format alive for the last two and a half decades – is that the plants are running to capacity and there is little space for them. Turnaround times for independents start at eight months and stretch on pretty much for ever.

Greener grooves?

Enter Jack White, vinyl warrior, with a demand that the majors invest in new plant and free up space for independents: “The issue is, simply, we have ALL created an environment where the unprecedented demand for vinyl records cannot keep up with the rudimentary supply of them.”

Throughout his video and the accompanying text there isn’t a single mention of the environmental impact of all this new plastic, or the plants that will need to be built to produce it. Meanwhile, all the majors have sustainability on their corporate agendas and since December 2021 have signed up, along with a host of indies, to the Music Climate Pact.

Have DeepGrooves had had any dealings with the majors?

“Yes! They are very involved with the whole process. Their complete capacity of requirements is of course impossible for us to fulfil, but we are trying to work on those. We did a project with King Gizzard And The Lizard Wizard in which we used recycled cardboard which goes around the sleeve instead of shrink-wrapping, and those things are being ordered by major companies and the bands really want their records to be produced by us, so there’s a change going on. The majors are hiring sustainability managers to make every part of the process more sustainable. I can’t share any details, but almost all of the majors are involved in this process”.

I reached out to Sony, Universal and Warners hoping to speak to an enthusiastic sustainability manager who could give me the low down on the majors environmental commitments, but was met with a wall of silence. Why? Shouldn’t green credentials be trumpeted on high? After all, the majors have all now signed up to the Science Based Targets Initiative, who claim that “Companies report that adopting a science-based target: Boosts profitability/ Improves investor confidence/ Drives innovation/ Reduces regulatory uncertainty/ Strengthens brand reputation”.

Sounds like just the incentives they need and some damn fine PR. With some tenacity I did eventually manage to get through to someone very helpful at Sony. Initially a little horrified that I managed to track her down she pointed me in the right direction but said she was “not sure I will be able to get sign-off from corporate comms to provide answers to your questions”.

Looking at the numbers helps to understand the corporate reticence regarding their green efforts, which actually appear to outstrip many independents. IFPI’s Global Music Report for 2021 says there is “very strong revenue growth” in the vinyl market of 51.3% in 2021, up from 25.9% the previous year — the 14th year in a row of growth. As Simon puts it: “Where are we with recycling? Where are we with non-toxic vinyl? Where has it ever been mentioned in those 14 years? The industry has found itself another little golden goose and it doesn’t want to do anything about it!”

My feeling is that with profits swelling on that scale, with a product that seems to sustain continuous mark-ups, anything that rattles consumer confidence must be buried. Sustainability press-releases from the majors focus on live music without mentioning work behind the scenes with DeepGrooves among others. Demonstrating any interest in green vinyl or packaging would inevitably suggest an admission that their premium product is in fact, toxic and unsustainable. With revenue growth like 51.3% on the year, no-one taking a cut of those profits will risk tainting the virtuous lustre of virgin vinyl, so the golden goose lives on.

Compared to other industries, music is a minor player in terms of environmental damage. But, as we’ve seen from the 40s onwards, music leads technology and changes people’s minds in every sense across social boundaries. When musicians, record labels and manufacturers go green, truly green, then that will be an enormous motivator to bigger polluters to follow suit. It maybe too late for ABBA, but what if an artist that demanded a release on green vinyl won a Grammy? Despite the seemingly unassailable power of the majors, the future is up to us. To prove the point, if it wasn’t for the independent sector doggedly, perhaps irrationally, keeping vinyl alive for 25 years then the majors wouldn’t have their golden goose.

Ruben concludes: “It starts with the consumer being willing to buy specific type of product. Most of the time the artists will follow, the labels then need to follow, then the pressing plants will need to adapt.

This is a chance for the music business to make good on its role as “an agent of petroculture” in the last century. Music can now be the driver of clean plastics, or move beyond plastic entirely, creating sustainable data storage that will sound and look beautiful for a lifetime.

Thankfully some of us at least, are rising to the challenge.