English-speaking music fans don’t clumsily refer to "underground and progressive German music of the 70s", because we have a handy shorthand: Krautrock. No such luck if you’re looking to refer collectively to a body of work that is just as challenging and impressive overall: the French avant-garde/progressive underground of the same period.

Throughout the 70s, both French and German musicians made some astonishing music: progressive, avant-garde, often anti-capitalist and usually a fuck you to Anglo-American blues-rock. Though never massively popular in their own countries, a few bands made an impact, playing live in the UK and the USA: Can, Magma, Faust, Ange. Come the 80s, the French and German undergrounds largely dropped off the radar of music fans in the English-speaking world for the best part of two decades.

Then came Julian Cope’s Krautrocksampler and the Freeman Brothers’ Crack In The Cosmic Egg. A narrative emerged that helped us understand the context of this innovative music, later developed and fleshed out by the likes of David Stubbs and Rob Young. You’d never have to tell a tQ reader that Krautrock is the result of the children of Nazi-era parents wanting to create a music that was distinctly German, yet owed nothing to their musical tradition, nor to blues-rock. We recognise Can and Neu! as among the great originators, and have record collections bulging with Popol Vuh and Amon Düül II represses. But Heldon? Lard Free? Besombes-Rizet? Not so much. France is different.

The French underground has stayed, if not invisible, then glowing only faintly and intermittently. Sure, there has been some English-language writing about it, and some championing. Magma get a lot of coverage; even sceptics are aware of Steve Davis’s heroic boosting of them to anyone who’ll listen, and the Eurostar is always dotted with British fans when Magma play in Paris or Amsterdam. If you look, it’s not hard to find features on Heldon and Richard Pinhas over the years, going right back to Neumusik fanzine in the late 70s and through Audion magazine from the late 80s. But right now, I feel the same as Julian Cope did about German music when he published Krautrocksampler back in 1995: that this music needs defining. It’s about time.

Over the last few years, growing to love this music, I’ve yearned to understand it better, to get a fix on why the music sounds the way it does, and why it could never have been made anywhere else. A credible narrative brings enough legitimacy for this music to overcome our inclination to dismiss French music, and I think I now have enough to start to define it. It seems to me that three forces made the 70s French progressive underground possible, and gave it its colour: riots, concrete and science fiction.

Welcome to the story of the ‘French Krautrock’.

Riots

First, we need to dwell on the Paris riots of May 1968. If you’ve grown up in the UK or US, it’s almost impossible to appreciate what happened 50 years ago and its impact on France. This is how close the French came to overthrowing capitalism: for six hours, the French state stopped functioning. President De Gaulle fled the country thinking the game was up, only to be persuaded back hours later by the military before many had noticed, while his wife had started passing on the family silver to their children. On his return, less confrontational policing calmed the situation, and revolution was averted, but the intense four weeks preceding had changed France for good. Student protests had gathered the support of the more radical trades unions, leading to factory occupations and a general strike demanding not just better pay and conditions, but deep change: worker control. It seemed briefly that the state would be overturned by intellectuals and workers in unison. Within living memory, the British have nothing remotely analogous; in comparison, the Poll Tax riots were a little local difficulty.

Even the methods of the almost-revolution pointed to new ways of doing, thinking and organising. One method of communicating with fellow revolutionaries was through posters – designed and screen-printed overnight with the day’s key message or slogan, and pasted up around the city. But if the methods were those of self-sufficiency, the messages were about collectivism ("this concerns all of us"), freedom ("it’s forbidden to forbid") and distrust for the state and bourgeoisie ("bourgeois – you don’t understand").

Those involved felt that anything was possible and an entire generation of intellectuals, students and artists never lost this sense of possibility, whether or not they had been out throwing stones themselves. The feeling, the certainty that change was possible, the need to question and reinvent was much more significant than examples of art directly referencing the May 1968 events, though there are some in both music and cinema, as you’d expect. Henri Weber, the USSR-born French politician who was on the streets in 1968 says, "Sixty-eight was a big step forward for democracy and liberalism, in the political and cultural sense. We took on all forms of authoritarian exercise of power". Some of the future protagonists of the music underground, such as Heldon’s founder Richard Pinhas, were active both physically – throwing stones – and intellectually in 1968, while the others would benefit from the milieu they created.

In the mainstream, French chanson continued to prevail, and Anglo-Saxon rock was the bread and butter for most major record labels. The underground was to grow gradually, partly in reaction to this, rather than flourishing as a direct expression of the events of 1968.

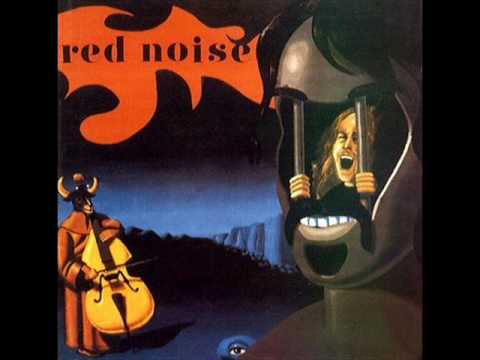

Music identified itself as underground by becoming increasingly strident and experimental, less familiar. Early indicators included Red Noise’s Sarcelles-Lochères (1970) full of scatological humour and musical skits. Magma were formed in 1969, by musicians with a jazz background and inspired by Coltrane’s abstraction. Moving Gelatine Plates formed in 1968, their debut album deliberately unsettling, even humorous, crafting something original with familiar rock and jazz instrumentation. This slow burn led to a creative peak between 1974 and 1979.

]Still, many underground French musicians of the 70s aren’t keen on citing May 1968 as much of a factor in their work, aside from occasional direct references such as ‘Ouais, Marchais Mieux Qu’en 68’, the retitled ‘Le Voyageur’ on Heldon’s debut, Electronique Guerilla . Their reluctance doesn’t alter the fact that the context is France at the time was very different to that in the UK.

Away from the creative side, you could also see the development of DIY approaches as distilling the spirit of May 1968: innovating well before UK and US indies were born, by taking control of every aspect of a release, from recording, through pressing to distribution, without the stifling embrace of a major label. ‘Le Voyageur’ (1972) and Electronique Guerilla (1974) were the first DIY single and album, released by Disjuncta Records years ahead of revered pioneers like New Hormones in the UK.

Concrete

The 70s underground was also drawing on a distinctly French tradition pre-dating 1968. By the late 60s, France had an established tradition of musique-concrète and experimental music from two very distinct sources.

It began with the birth of post-production, made possible by the invention of magnetic tape. The GRMC (Groupe de Recherche de Musique Concrète) was set up by Pierre Schaeffer and Pierre Henry in the 50s, working as part of public service broadcaster RDF. Superficially, it was the equivalent of the BBC Radiophonic Workshop, though more in method than in purpose. Theirs was art for its own sake: they looped, sped up, slowed down, used ‘natural sounds’, creating new compositions for broadcast without the need to focus on sound effects and TV themes. The GRMC evolved into Schaeffer’s GRM (dropping the "concrete" in their name) in 1958. In the context of the challenge posed by the subtitle of David Stubbs’s Fear Of Music: Why People Get Rothko But Don’t Get Stockhausen, this is worth dwelling on. The Groupe de Recherches Musicales was a government-funded national agency, not a group of hobbyists. Its music was at the cutting edge, and its influence firmly felt in the development of post-war music internationally, effectively birthing the use of ‘studio as instrument’ and redefining what can be meant by ‘music’. Again, it’s a struggle to understand this from a British perspective: GRM’s intellectual standing compared to the Radiophonic Workshop is telling.

Closer to the mainstream, France had recently seen an influx of African American avant-garde musicians. In Paris they got a fairer hearing and more respectful audience than in the USA, and free jazz was big news. Musicians referred to it as the "new thing" and it featured regularly in major national newspapers and weeklies such as Le Monde and Le Nouvel Observateur. This wasn’t just an intellectual pursuit; it was cool. The independent label BYG was set up to release music by these artists, and soon added French acts to their roster, including the underground Ame Son. So artists and, to an extent, the public were comfortable with abstraction and improvisation, which opened an irregularly shaped door that the progressive underground could step through. In the early 70s some French underground artists, such as Moving Gelatine Plates and Lard Free, were not far from free jazz territory.

The essential thing about experimental and avant-garde music has always been the emphasis on newness. The use of the latest technologies and new ideas about music creates a sense of possibility and, as the early 70s developed, a music emerged whose heritage and influences weren’t clear. The exemplar for this newness is the first Heldon album, Electronique Guerilla (1974). Every track except one variously uses repetition, processing, layers and loops to create something described by Adrian Sparks in Neumusik as "an aura of disquiet, yet peaceful". Released before Fripp & Eno’s (No Pussyfooting), it shares a passing resemblance to that album in places, though harder-edged, but sounds like nothing that had gone before.

Science fiction

If the post-war history of experimental music and the Paris riots helped create the environment in which the underground played out, then science fiction completes the trinity. It’s part of the grammar of this music, evident in song titles, imagery and concept. Magma devised an alien language (Kobaïan), then wrote and sang in it for decades, creating some of the most dramatic music you’ll ever hear, telling tales of invasion and redemption. And Bernard Szajner, as Zed, released a beautiful album of soundscapes, Visions Of Dune , inspired by Frank Herbert’s Dune , years before David Lynch and Toto got their hands on it.

And there was Heldon. The band name is taken from Norman Spinrad’s Iron Dream: it’s the fictional totalitarian analogue of Nazi Germany in the novel-within-the-novel written by an alternate-history Hitler. ‘Zind’, a track on their first album, is Heldon’s rival country, and ‘Zind Destruction’ features on a later album. Other Heldon work would include explicit references to Dune and Michel Jeury’s Chronolysis, and Heldon’s Richard Pinhas is on record about the influence of other new wave science fiction authors such as Philip K Dick. Beyond the many record sleeves in the French progressive underground with images inspired by SF, fantasy gets a look in too, with echoes of HP Lovecraft’s fiction. Nyl’s only album includes the track ‘Nyarlathotep’, named for a god in Lovecraft’s cosmic horror universe.

Again, the contrast with the 1970s UK and US is striking. In the English-speaking world, though much less the case now, cultural gatekeepers tended to see SF and fantasy as lowbrow, for teens and geeks, and comics – even when called ‘graphic novels’ – as throwaway. In France it couldn’t have been more different, where SF has always been a legitimate literary genre, and comics ("bandes dessinées") have enjoyed the same status as film, poetry, theatre and other literature for decades. The underground is a serious place, and these SF references are not trivial.

This science fiction backdrop does seem unique to France, and has no parallel in German music. Krautrock does, of course, revel in its own cosmic imagery: Tangerine Dream’s first few post-Schnitzler & Schulze album sleeves were beautiful things but, like their music, it’s a sense of space that’s being conveyed. Likewise, the sleeves of Schulze’s Irrlicht and Kraftwerk’s ‘Kometenmelodie’. And Cosmic Jokers’ Sci-Fi Party is tongue-in-cheek. German artists didn’t choose to convey modernity through SF.

Was there a French version of Krautrock?

If we agree that there is something coherent here, then it seems right to ask if there was a ‘scene’ as such, even one without a name? Well, yes and no. Similar to Germany, there was no named ‘French Krautrock’ scene, but there was no lack of musicians chopping and changing between bands, not to mention side-projects making far better albums than side-projects have any right to. Two examples, though there are many more: Magma’s Laurent Thibault went on to produce Weidorje, whose only album took the Zeuhl sound to new heights, as well as releasing a beguiling one-off solo album, Mais On Ne Peut Pas Rêver Tout Le Temps. Keyboardist Patrick Gauthier was a member of Magma, Heldon and its predecessor Schizo, who was also in Weidorje and later released his own solo album, Bébé Godzilla .

The closest this diverse music had to a hub was Heldon founder, Richard Pinhas. He set up Disjuncta Records, played with Lard Free and guested on albums for Patrick Gauthier and Pascal Comelade as well as his Heldon bandmates Georges Grünblatt and Alain Renaud. Read between the lines and he’s also, using aliases, the main player on 1980 modernist classic Ektakröm Killer by Video Liszt.

Scene or no scene, there’s a way of defining and understanding this innovative and compelling music. The narrative as it is – riots, concrete and SF – gives us a decent way to describe the terrain it occupies and some of its aural and visual grammar.

Maybe, in the end, we’ll decide that the 70s French underground is just not as good as its German contemporary. It’s certainly true that, in the French camp, we don’t have gateways in the form of tracks like ‘Vitamin C’ or ‘Hallogallo’, sampled in hip hop, featuring in film soundtracks, and cited as influential by numerous current artists. And neither is there a French Kraftwerk, a group beyond famous and uniquely associated with their homeland.

But I’m convinced that the quality of the best fifty or so albums more than matches what Germany had to offer during the same period. So I’ll keep banging the drum for this music, whether or not we find a better name for it than ‘French Krautrock’.