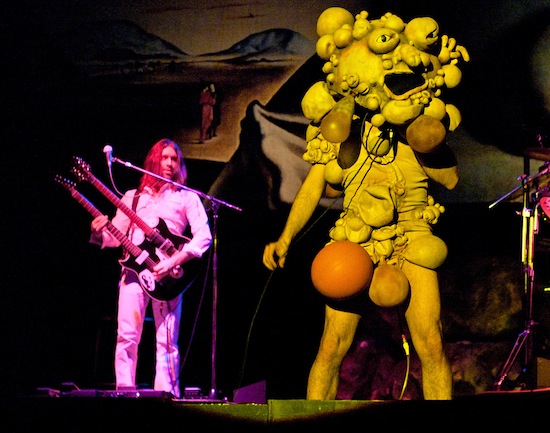

I’d been living in Paris no more than a couple of days when I noticed the poster advertising a live performance of The Lamb Lies Down On Broadway just near my house. Peter Gabriel left Genesis way back in 1975 and the band are now defunct, so such an extraordinary claim piqued my interest: a group from Quebec calling themselves The Musical Box would apparently pass through town and perform the prog five-piece’s cumbersome double concept album in its entirety at Le Bataclan on Boulevard Voltaire. I decided I should be there.

A cursory internet search revealed they’d be re-enacting the show from start to finish as it was in 1974, down to the costumes, the choreography (the show was less spontaneous gig than scripted rock opera so most moves were choreographed) and with the original slideshow arranged on stage in a triptych projected across the backdrop throughout. The slides were thought to have been lost forever until they were located at Genesis’ The Farm studios in Surrey by the Musical Box themselves. But even with the projected images recovered, it wouldn’t be easy. The original show was never filmed – meaning there would be scant reference material to work from. Genesis reportedly suffered technical glitches throughout a world tour blighted by poor ticket sales, and Gabriel terminated his position at the helm of the group at its conclusion in order to spend time with his family.

The motivation to re-enact a concert that so famously floundered is unusual enough to grab one’s attention, but then the mind boggles when you start to consider the complete immersion required, the effort researching equipment and learning the parts and the untold hours spent assiduously perfecting what is essentially an illusion. The players in The Musical Box would have had no memory of the show on account of being too young to have seen it, so any charge of sentimental yearning for halcyon days must surely be a false one.

Pop culture, we’re forever being told, is becoming more and more reliant on its heritage, and if the music industry is milking nostalgia then we’re only too happy to suckle at its bosom. Mainstream festival lineups now more resemble a best of the 90s than a showcase for thriving new talent and it’ll be harder to determine what year it was in the future just by looking at a vintage poster. Venerated albums of 20 years ago get repackaged and written about all over again, while 2013’s hottest song, Daft Punk’s ‘Get Lucky’, brazenly plunders 70s funk and disco with the help of Nile Rodgers. Music can so often be the sum of its parts, the homogenisation of its influences and little more, but what about when the protagonists reach back into the past to gather up just one source alone, and then set out to systematically copy every detail, from the stage props to the analogue equipment that manufacturers stopped making decades ago. Björn Again this ain’t.

The re-enactment is nothing new. In 1973, the Egyptian army invaded Sinai in a bid to reclaim land, and the onslaught against the Israelis was so successful that they decided to restage it a year later for posterity, given that cameras had been banned from the initial attack by Egyptian authorities (two of their own soldiers were killed in the ensuing re-staging). In 1998 Gus Van Sant attempted a shot-for-shot colour remake of Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho complete with the same soundtrack, much to the consternation of critics. In art, the reenactment became extremely popular between 1996 and 2006, and the latter half of this flurry of activity coincided with Vivienne Gaskin’s directorship at the ICA in London where she commissioned no less than seven re-enactments. Jeremy Deller is probably still better known for his 2001 reenactment of the Battle of Orgreave – a 1984 clash between miners and police – than he is for the work that won him the Turner Prize in 2004 [the film Memory Bucket].

In music, regurgitation is very much in vogue, though an album being replayed again live, years after the fact, does not constitute a re-enactment in its purest form. Most musical reenactments in the art world – like, say, The Cramps 1978 show at the Napa Mental Institute restaged under the tutelage of Iain Forsyth and Jane Pollard at the ICA – are one-off installations mimicking the event they seek to represent in detail and duration, so they will attempt to conclude when the other concluded. The Musical Box are less a tribute act, more an anomaly; they stand alone as persistent offenders, taking their shows around the world and restaging them night after night after night.

"I hate saying this but nobody’s doing anything anywhere close to what we do," says Sébastien Lamothe, musical director of The Musical Box and Mike Rutherford impersonator, when I meet him before the show in Oberkampf. "It’s really about the respect we have for what Genesis created and our sincere intention to try to offer the audience something as real and authentic as we can. In every possible way. You wouldn’t believe the lengths we go to get the littlest pieces of equipment."

I wondered if Sébastien has any duality issues, where he’s started to believe he is the Genesis guitarist.

"We’re not trying to imitate [Genesis] physically," he tells me. "Obviously we’ll try and dress appropriately and have a certain persona on stage for people to relate to so it doesn’t break the illusion, because that’s what we’re trying to create, a reenactment and an illusion. I’m not Michael Rutherford! I am as a musician extremely sensitive and very interested in trying to incorporate and understand how he wrote those songs."

Sébastien says that on some level they do become the players on stage though. "We’re actually putting ourselves in the exact same position they were at and using the same vintage equipment – so in some ways, yes [we do become them]."

Do their personalities correspond with the personalities in Genesis?

"I took the role of Michael Rutherford in the band because sometimes I’m doing the rhythmic part of the songs, the structural part, so I kind of lead a bit from the back, which means I’m very concentrated and serious on stage. I play all these pedals on the floor, I have all these guitars with open tuning, so I’m forced to become him for about two hours every performance.

"Our Phil Collins is very flamboyant in his physical performance, because he has to be with this massive drum kit. And he’s a bit goofy on stage, it just comes naturally. So in some ways we are forced to become those roles."

Sébastien rejects the notion The Musical Box are a tribute act.

"We’ve been fighting this image of a tribute or homage or covers band," he says. "We don’t mean it in a pretentious way, but we really, really research this stuff and the reenactment is certainly accurate. It’s an ongoing process and it’s not something we’re going to stop doing ever".

A few nights previous, Lamothe says a former drum tech of Phil Collins came to their show in Zurich, and it was an opportunity for the counterfeit Phil to pick his brains and glean information about equipment. If knowledge is power where the Musical Box are concerned, then for Iain and Jane’s Ziggy Stardust reenactment at the ICA – A Rock and Roll Suicide – fandom was actually a hindrance. They auditioned dozens of musicians to play the role of David Bowie’s alterego.

"Those who approached the role primarily as super-fans were the first to be rejected," they told me, "precisely because their obsession got in the way. A super-fan looks at an artist in a different way, and we found that performers coming from that perspective found it impossible to ‘forget’ the knowledge they had accumulated, so you’d see someone for an audition who would be singing a track from the 1973 set and they’d be throwing in all these gestures and moves that were incredibly Bowie, but post-1973 Bowie. They ‘knew’ things about Bowie that Bowie himself didn’t know at the time he last performed his Ziggy Stardust creation."

Mythology is clearly an enemy to the conceptual artist. This is something Jo Michell discovered when she attempted to recreate Einsturzende Neubauten’s 1984 Concerto For Voice & Machinery at the ICA, an event which quickly descended into chaos and acts of random violence just 20 minutes into the performance. Mitchell spent a year researching the event, speaking to eyewitnesses, reading about it and quizzing the likes of Blixa Bargeld. As it transpired, although Bargeld said he thought it was a "charming idea", he didn’t remember much from the event, and while it has passed into Neubauten folklore, it was actually scored by Mark Chung and featured guests Genesis P. Orridge, Stevo and Fad Gadget. So not technically a Neubauten show at all, although there were electric drills and cement mixers.

"As a pure reenactment it was doomed to failure," Jo told me. "There was a relationship between the two [events]… but the more I found out the more I felt justified doing it. Because I wasn’t there at the original performance I didn’t have any romantic or nostalgic attachment, and I’m certain I wouldn’t have done it had I been at the ICA in 1984."

I wonder if a reenactment somehow keeps the original moment alive in some way.

"I’m not sure about that," says Jo. "I don’t think it does. It raises questions around authenticity and the lived experience, memory and collective memory, but keeping the experience alive? That didn’t happen."

"We’d say it depends on the project," say Iain and Jane, "but we can only really speak for ourselves, and for us our projects were always separate events – not entirely separate perhaps – but certainly something that needs to be considered on its own terms unlike, say, a theatrical tribute show which serves only to keep the past moment alive in memory. Our focus is on contemporary culture and how overlaying or superimposing an event from the past onto the present affects the audience."

What about Vivienne Gaskin who commissioned so many of the pieces, did she think it kept the moment alive? Jo Mitchell certainly alluded to the fact that she did during our conversation, having shared a round table with her around the time of the second event.

"Musical reenactments fill a void," she told me, "a need created by the cultural capital traded after an iconic pop moment. The few who saw it together with the critics, footage and PR, create the historical moment. To recreate this moment is to harness these accounts together in a new live moment, in which the audiences are complicit, and are agreeing that the moment be brought to life."

So it’s not a separate event then? Is it in a sense a continuation?

"The cultural moment has to be alive," she says, "by which I mean relevant or vital to the now, not consigned to historical anecdote in order for the re-enacted version to be critical. It is however a separate event which has proven to create its own histories independent to the authentic act."

Given the amount of preparation a restaging takes (Jo Mitchell said she worked on the Neubauten ICA event for a year), does Vivienne think a reenactment is more about fastidiousness than art?

"The artists I have had the privilege to work with on reenactments are the most obsessive in nature I have ever met. It requires that kind of personality, obsessive researching, obsessive powers of persuasion, obsessive collecting to make it work. I’m not certain if it is more fastidiousness than art – but the personality of the artist requires that quality to create the most overwhelming acts of art."

"For us, no," reply Iain and Jane to the same question, "we always knew that it was important to get the details right – but our ends were best served by getting the spirit right, rather than the fastidiousness of getting every last geeky detail right, but forgetting about the beating heart and soul of the live experience."

Simon Reynolds covers art reenactments of musical events in his book Retromania, and rather sniffily he concludes that "no matter how much research and preparation goes into reenactment, it is doomed to be an absurd ghost, a travesty of the original". And yet the motivation of the conceptual artists themselves doesn’t appear to be about nostalgia at all. The ultimate goal is surely failure, because the attempt to recreate a carbon copy of an event is – and will always be – a futile one. Perhaps it’s akin to a person striving for perfection, an unattainable ambition, but that’ll hardly stop us trying.

If we have become consumers of nothing but re-packaged goods, then what does the re-enactment – the sincerest form of flattery – say about the state of our culture? Is the fact that re-enactments are being made in the first place an indicator that we’ve run out of ideas?

"I severely hope not," retorts Jo Mitchell, sounding slightly annoyed at the mere suggestion. "I don’t think we have at all. Influence has always been there. Re-enactment is kind of a question of originality. Neubauten weren’t completely original working in that area of industrial music, and when I was looking into it, people were saying, ‘God that was a lightweight gig’… We might think of it now as amazingly original but it wasn’t. So no way, not in anyway could we be running out of ideas anymore than people were in the 1980s. It would take me a long time to try and confirm or justify that but I simply don’t believe that."

"The idea that we’re running out of ideas isn’t a particularly new idea," say Iain and Jane. "We’re only a generation or two away from a time where the older generation – our parents and grandparents – didn’t have a youth culture to be nostalgic for. Our own grandparents grew up in a world before teenagers, before rock & roll, before television. But increasingly that’s not the case, and as generations with disposable income become interested in recapturing their own youth and the culture that was important to them in their formative years, it’s no surprise at all that our cultural past is constantly resurrected. Does that mean we’re running out of ideas? We’d say it doesn’t."

Vivienne doesn’t agree either: "This is a sweeping statement which is true of genuine acts of nostalgia (bands reforming to wheel out old tracks etc…) Re-enactment has nothing in common with nostalgia, it wasn’t a longing for the glory of the past but a pure live experience devised and created in the here and now. The fact that the major re-enactments have created their own histories or nostalgic memories in themselves is perhaps the most convincing arguments in support of this."

So it has nothing to do with nostalgia then?

"Nostalgia was never really important to us," say Iain and Jane, who have moved away from reenactment but are still working within the realm of pop culture, working with the likes of Scott Walker and Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds on various projects. "You can’t make the sort of work we have and claim to not be interested in nostalgia, but it was never a motivating force in the work, we were interested in the here and now, trying to say something about the present through the past. Nostalgia might be a point of access, but it was never the point of the work."

The Musical Box admit that when they started out in the 1990s, a lot of the fans who came to see them were reliving the records they loved from the 70s, though now large sections of their audiences weren’t alive when the original records came out. So if the audiences aren’t there for nostalgia, and they’re not there because of nostalgia, then why is Sébastien still dressing up as Mike Rutherford every night 20 years later?

"To be honest with you, we’re questioning ourselves all the time," he admits. "Is this relevant? Why are we doing this? And in the end the answer is always pretty much the same. We’re the frontline. If we don’t do this then this doesn’t exist. And it’s a lot of fun, and it’s worthwhile for us."

Finally I email Jeremy Deller, who responds before I’ve had time to put the kettle on. His answers are brief, but revealing nonetheless. I put the same questions to him as I had to Vivienne and to Jo and to Iain and Jane. Does a reenactment keep a moment in history alive or is it an entirely separate event? "It jogs the memory," he says. Is reenactment more about fastidiousness than art? "Not for me," he replies.

Have we run out of ideas? "No." What’s the purpose of a musical re-enactment? Is our past catching up with us? "No. It’s getting historicised," he says. And finally, he was 18 in 1984 when the original Battle of Orgreave took place. Was there any element of nostalgia in his motivation?

"No," he replies, "nostalgia suggests enjoyment and happiness."