October 20, 1973, was a mercilessly windy day. The Queen was officially opening the Sydney Opera House and struggling to hold onto her speech notes. Grasping the pages with both hands, she said, “Every great imaginative venture has had to be tempered by the fire of controversy.”

The Queen was referring to chronic problems in the construction process and how in 1966 – two years after the originally scheduled completion date – the building’s Danish architect, Jørn Utzon, walked from the project calling his confrontations with politicians “malice in blunderland”. But you wonder whether she may also have been obliquely acknowledging the founding father of the Sydney Opera House, an English conductor and composer called Sir Eugene Goossens.

She’d met Goossens. In October 1955, he flew from Sydney to London to be knighted for services to Australian music, eight years after he moved to the country to become director of both the Sydney Symphony Orchestra and Sydney Conservatorium of Music. The newspapers were aghast that his salary exceeded the then-prime minister’s, but he came with impeccable experience and status. Goossens’s father and grandfather were also celebrated conductors, and his siblings were distinguished musicians, too. His career began after World War I in London, where he conducted the British concert premiere of Stravinsky’s Rite Of Spring, and took off in America between 1923 and 1946, where he became the chief conductor of the Rochester Philharmonic and Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra. Bringing him to Sydney was considered to be a coup, and he was handsomely rewarded – with money, fame, and power.

Four months after receiving his knighthood from the Queen, Goossens got caught up in a scandal that demolished his career and threatened to derail his dream to build an opera house for Sydney. Utzon was a year away from winning the international design competition that would lead to the marvel on the harbour. It was still in planning stages, with Goossens leading the charge and lobbying hard.

“If you’ve been to Sydney, you’ll know the Conservatorium sits on a hill overlooking the city on the one side and on the other side the harbour,” says Dr Drew Crawford, an Australian musicologist based at Southampton University. “Between those two views is this little promontory. When Goossens was employed as the director of the Conservatorium, he looked out of his office at this view and between these two points were some tram sheds. He said, ‘We need a performing arts centre, we need an opera theatre, and that’s where it should go.’ There were very few people who could have that vision, articulate that vision, and also have the ear of the politicians; to be able to talk to people to get it going. So, really, there would be no opera house, certainly not as we know it, without Eugene Goossens.”

I spoke to Crawford while making a documentary on Goossens for Radio 4 and there was much else he told me. He said that Australia felt it was clever to persuade this “orphic figure to come down under to bring us the gift of music”, but actually he’d become persona-non-grata in America. He’d slept, Crawford said, “with almost every woman that had anything to do with the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra”. He was a debonair sort, already onto his third wife when he arrived in Sydney, but he was also reserved – in person and in his conducting style. His niece, Jennie Goossens, an actor last seen in Ted Lasso, told me: “He was quiet, and very gentle, and sweet. He had a very sweet nature.”

The Australia that Goossens landed in was the one that Barry Humphries, Clive James and Germaine Greer – all kids in the 1940s and 1950s – ran away from. It was conservative and still looking to Europe for a sense of cultural identity. Goossens slipped in deliciously. His profile became such that it took me three full days to trawl through many thousands of mentions of him in the Australian newspaper archives. He turned the Sydney Symphony Orchestra into a top-ranking outfit, but there was never a sense that he wanted to keep classical music for the elites. He toured the orchestra relentlessly and played free outdoor concerts to 25,000 people. After one concert, it was reported that he was “mobbed by girls”, although he was in his 50s. It was a pre-rock & roll, pre-teenager era. Without pop idols, Goossens became a celebrity as we understand one now, and he was a canny operator to boot. He would follow successes with very public pleas for improvements to Sydney’s musical infrastructure, including his grand trophy – building an opera house where those tram sheds were on Bennelong Point.

Eugene Goossens

The trip Goossens took to Europe in October 1955 to pick up his knighthood and guest-conduct concerts was an unusually long one – five months. He had time off and, in those moments, he had no clue that he was being followed. When he came through Sydney’s Mascot airport at 8am on the morning of 9 March 1956, he expected to be waved through customs as usual. But he was stopped. He was taken to a small annexe and interviewed. Six bags and his briefcase were seized. In them, were 1,166 pornographic images, pornographic films, sex books, incense, literature relating to the occult, and several rubber masks. The images were hidden in brown paper envelopes marked Beethoven and Brahms, as if they contained musical scores.

It took ten weeks for Goossens to leave Australia, never to return. He resigned from his posts at the Sydney Symphony Orchestra and Conservatorium, shortly before he was inevitably sacked, and accepted a maximum fine of £100 for importing prohibited goods. During those last weeks in Sydney, he must have winced reading headlines like, “Big Names in Devil Rite Probe,” and, “Participants in Black Magic sex orgies in Sydney have been blackmailed over their activities.” But he’d hardly helped his own cause. It was Goossens, via his lawyer, who claimed that he’d brought the material in “under duress”. Even as he flew back to Europe on 25 May, he was circuitously referring to “persistent menaces” sealing his fate.

In a 1988 book, The Strange Case Of Eugene Goossens, the former press secretary of the Sydney Opera House, Ava Hubble, wrote, “The pornography case that ruined him remains one of the country’s most puzzling mysteries.” She ran through the theories of what happened, each more succulent than the last. I posited them to Drew Crawford to gauge his opinion. Was Goossens being blackmailed, as he claimed? “No.” Was he being set up by a rival conductor, Bernard Heinz, who possibly had an eye on his job? “No.” Could he have been stitched up by rival politicians keen to scupper plans for the Sydney Opera House? “No.” Was he sold out by his third wife, Marjorie, either because she wanted to have an affair, or because she was jealous that her husband was having an affair? “Marjorie was already having many affairs of her own, no.” Was Goossens the fall guy to protect an Eyes Wide Shut-style, high-society scene of occultism and fetishism? “Not that I’ve seen, no.”

Rosaleen Norton

In the early 1950s, Goossens found a book by a local artist, Rosaleen Norton, in a Sydney gallery. The Art of Rosaleen Norton featured paintings like ‘Black Magic’ and ‘Rites Of Baron Samedi’, and poems by her bisexual lover Gavin Greenlees. They had titles like ‘The Angel Of Twizzari’ and ‘Esoteric Study’. Impressed by the book, Goossens got in touch and met the pair for tea at their flat in the run-down, bohemian quarter of Sydney, Kings Cross. It was near the Sydney Symphony Orchestra’s rehearsal space and he became more than a regular visitor. He became infatuated with Norton, with whom he was soon practising rituals of sex magic.

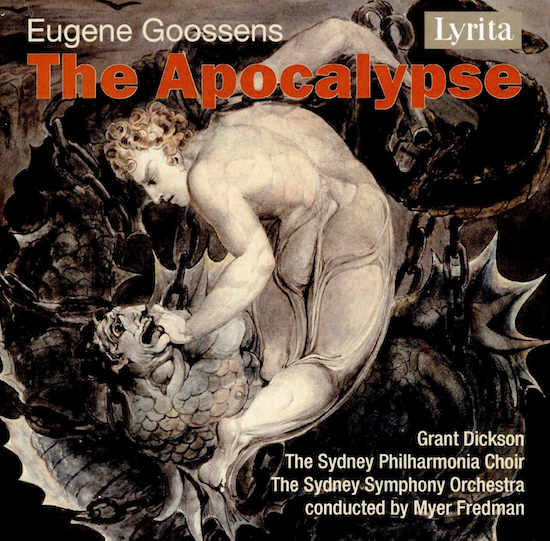

There’s long been a misogynistic theory that Norton, a Pan worshiper known as the Witch of Kings Cross, malevolently drew Goossens into her dark web of intrigue and subsequently ruined his career. It’s not true. Goossens’s interest in the occult went back to England in the 1910s and his friendships with fellow composers and occultists Cyril Scott and Peter Warlock. In Norton and Greenlees, he identified two like-minded practitioners and he was far from embarrassed by forming a strong bond with the couple. He gave them free seats for the opera. Norton also became a key inspiration for the Satanic scenes in a vast-scale oratorio, The Apocalypse, which Goossens premiered at Sydney Town Hall in 1954. He considered the work to be the apogee of his composing career. It’s clumsy and constantly teetering on the hammy, but it’s audacious and it has been recorded, most notably by the Sydney Symphony Orchestra conducted by Myer Fredman.

For years before Norton met Goossens, her art had fallen foul of Australia’s ruthlessly tight obscenity laws. She was on the Vice Squad’s radar, and also ripe for exploitation by bad actors on the make. Two such opportunists, Francis Honer and Raymond Ager, infiltrated her coven in 1955 and stole a roll of film. They developed it and discovered photographs of Norton and Greenlees enacting a ritual of sex magic. “She’s lying on her back, tied to a table covered in a picnic blanket,” Crawford told me. “Gavin is standing over her in robes. They’re both wearing masks. He’s brandishing a ritual dagger and inserting coins into her vagina.”

Honer and Ager tried to sell the images, but no newspaper in the Australia of the 1950s would risk publishing them. Instead, the editor of the tabloid The Sun turned the two men over to the Vice Squad. In exchange, the Vice Squad allowed a crime reporter from The Sun to accompany detectives on a raid of Norton’s flat. It produced gold – a bundle of letter signed ‘Gene’ or ‘Genie’ tucked behind a sofa. They were from Goossens. “Contemplating your hermaphroditic organs in the picture nearly made me desert my evening’s work and fly to you by first aerial coven,” he wrote in one. “But, as promised, you came to me early this morning (about 1.45) and when a suddenly flapping window blind announced your arrival, I realised by a delicious orificial tingling that you were about to make your presence felt.”

The detectives were smarter than Honer and Ager. They realised that the prize was Goossens, not Norton or Greenlees. They’d been speculating since the premiere of The Apocalypse whether the most famous cultural figure in Australia was somehow tied up in an underground scene of witchcraft and sex magic, and now they had proof. Crusaders against what they considered to be filth, the Vice Squad placed Goossens firmly in their crosshairs and waited for him to slip up.

Goossens had explicitly told Norton to get rid of his letters. She didn’t. The raid made the papers, after which Goossens destroyed his collection of pornography, ritual garb, and esoterica – mostly bought in Europe, where such material was more readily available. But he wasn’t raided. On that trip to London to pick up his knighthood, he was replenishing his stash, blissfully unaware that the Vice Squad had eyes on him. They had no resources to send detectives to London, so they paid local journalists to follow him. The drama at Sydney airport on 9 March 1956 was a sting. They had their man.

We don’t know how explicit the 1,166 pornographic images or the films were, because the Vice Squad destroyed them. Sex books seized had titles like Sharing Their Pleasures, Continental, and Flossie And Nancy’s Love Life. They sound tame and it makes you wonder whether the pornography was too. The police reports made for awkward reading, but they don’t suggest that Goossens’s rituals of sex magic with Norton and Greenlees involved much more than mystical cunnilingus. “We undressed and sat on the floor in a circle,” he told detectives. “Miss Norton conducted the verbal part of the Rite. I then performed the sex stimulation on her. I placed my tongue in her sexual organ and kept moving it until I stimulated her.”

Significantly, the police took no further action against Goossens. A sub-drama played out in the papers over the next few days about whether he could survive contravening a customs charge, but he couldn’t. In the 1950s, and until 2007, the Sydney Symphony Orchestra was run by the Australian Broadcasting Corporation. For the documentary, I spoke to the current chairperson of the ABC, Ita Buttrose, and she suggested that Goossens would probably still be sacked today. “He had a wide range of interests,” his niece Jennie told me with wonderful understatement. They were enough to blow up his career.

The Goossens scandal was caused by a possibly ill-advised but perfectly consensual affair between a classical music titan and an artistic witch. But rumours do persist. Goossens’s claim that “persistent menaces” forced him to import the material hinted a bigger conspiracy and there are loose ends in this story. The chairperson of the ABC in the 1950s was Sir Charles Moses and he was tipped off about the bust at the airport by a man called George Dovaston, about whom I have found out exactly nothing. Moses thought it was a crank call. Also, Drew Crawford told me, “Very, very wealthy media baron Frank Packer paid off Rosaleen Norton’s legal bills when she was being sued for obscenity. But that could also be interpreted as being someone wanting to change the censorship laws in their own favour, to further their political ends.”

What bothers me is that those I spoke to who knew and loved Goossens remain convinced that other forces were at play. Jennie said, “No one talked about it, certainly not in public. But I know pretty well that it was a setup and that people in very high places would have been involved.” The conductor Richard Bonynge, widower of Australia’s most famous soprano Joan Sutherland, said, “He was a wonderful, wonderful man. I spent over two years in classes with him at the Conservatorium and he was kind, and he was extremely knowledgeable and helpful, and what he did for Sydney cannot be thought of. He put Sydney on the map, musically. It’s a disgrace the way Australia treated him. I don’t believe it was anything more than a setup. Somebody was out to get him.”

Goossens died in 1962, aged 69, six years after the scandal. Bonynge and Sutherland visited him after he left Australia, only to discover a broken man. He did work again, releasing a series of explosive albums with the London Symphony Orchestra in 1959 and 1960, but he died not knowing whether the Sydney Opera House would ever be completed, let alone that it would become a UNESCO World Heritage Site. However, we do know that he admired Utzon’s spectacular shell design. After the Dane won the 1957 architecture competition, Goossens wrote to the Sydney Morning Herald to congratulate the judges on their “courage and vision”. He thought Utzon’s design was “a magnificent conception”, adding: “If this building really goes up on the Harbour, I shall be proud of having been associated with its conception.”

His comments were printed on the front page. In disgrace, he still had clout, but it didn’t last. He wasn’t mentioned in speeches by politicians at the opening of the Opera House, nor did calls by musicians to name a hall after him come to anything. There is a bronze bust of Goossens in the halls of the Opera House, erected in the 1980s, but he’s a largely forgotten figure, unlike Rosaleen Norton. Greenlees died in 1983 after multiple, lengthy admissions to psychiatric hospitals. Norton died in 1979 and has rightly found herself recast in the 21st century as a feminist icon and proto-counter cultural hero. “She riding a wave,” Marguerite Johnson, a cultural historian, told me. “People are more interested in her, the outcast of Australian cultural history, than they are in Eugene. I think that’s a monumental mistake. He was a giant, and he occupies such a pivotal role in the cultural history of Australia. My goodness the gravitas of that man. He needs to be written into our history books asap.”

Listen to A Very Australian Scandal on BBC Sounds from October 3