Sometime in the early 1980s, Elton John bought a tram. On a downer after a multi-day bender, he sought solace in buying the carriage, which had to be shipped over from Melbourne and manoeuvred into his back garden by two helicopters.

It’s tempting to treat Elton John’s 1976 purchase of Watford football club as similarly ridiculous; the folly of a rich, lonely man with a major substance abuse problem, endlessly searching for something, anything, to fill the void within. And yes, he was certainly seeking comfort through involving himself in the club (his only positive childhood memories of his father were of standing with him on the terraces of Watford), but it ended up being the most remarkable thing he ever did.

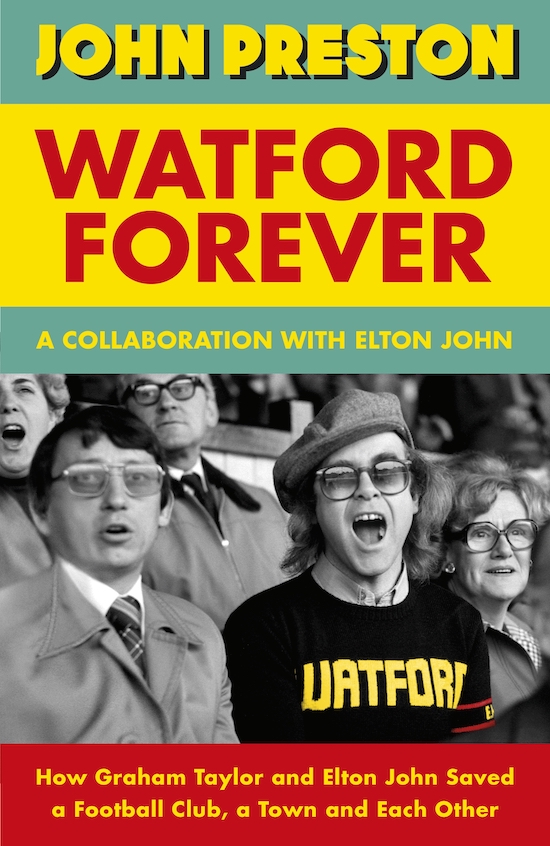

John Preston’s book Watford Forever, a collaboration with Elton himself, is the first to tell this story in any depth. It’s partly the story of the extraordinary friendship between Elton and Graham Taylor, whom he brought in to manage the club in 1977. Within four seasons they took a broken-down, unloved and nearly bankrupt club from the bottom end of the old Fourth Division to second place in the old First Division. Watford played in Europe, reached the FA Cup Final and, by the time Taylor and Elton stepped down in 1987, were a well-run club on a sound financial footing with pioneering facilities for families and deep connections with the local community.

It’s not a story that makes much sense today. It was barely believable at the time. As Preston shows, Elton didn’t simply get out his chequebook and buy success. Taylor actually underspent the £1m budget for players that he’d agreed with his chairman would be the minimum required to take the club into the First Division. Four of his players stayed with them for the entire journey. Much of the money Elton John put in went on improving the Vicarage Road ground and building a proper management set. Viewed from the vantage point of an era of mega-clubs owned by billionaires and sovereign wealth funds, all of this seems like a story from another age, when a millionaire could take a team to the top without making too much of a dent in his fortune.

This was success done the right way. Elton John put in the hours: Backing his manager, chairing board meetings, reaching out to potential players in the transfer market, attending game after game in unlovely lower-league stadiums (often facing homophobic abuse for his pains), dialling into local hospital radio match commentary whilst on tour. In return, Elton got community, familiar routines and in Graham Taylor, a friend who wasn’t impressed by showbiz glamour. An unhappy, lonely, drug-addled mess for most of his chairmanship, Watford was the one fixed point in his life. Elton claims in the book that it was Taylor who, in telling him to his face that he had a problem, started him on the road to eventual rehab and recovery.

In reading Watford Forever I was struck by how little of this story had been told before. As a lifelong Watford fan who had the privilege of having a season ticket through most of the John/Taylor years, I knew at the time that I’d witnessed something very special. But when I have met football fans or Elton John fans outside the UK (now or at the time) it’s always surprised me how little the story resonates. The otherwise excellent 2019 biopic Rocketman doesn’t go into it at all. Me, his hugely entertaining autobiography of the same year, does tell some of the story, but he soft-pedals the extent of his involvement and the sheer number of hours he put in at the club

The story of Elton John at Watford doesn’t really fit. What would have fitted would have been a flamboyant celebrity adding glamour and razzmatazz to a terminally unfashionable club. Everyone can understand that story; like Michael Jackson’s visit to Exeter FC or Ryan Reynolds and Rob McElhenney buying Wrexham, and the performative celebrity football fans in the Britpop era.

Elton’s involvement with Watford was not a rich man’s dalliance. True, he has played concerts at the ground a few times over the years, but these were benefit gigs for the club. He was serious. He didn’t bring famous friends to the ground; he didn’t take the mic and try and lead supporters in chants, he never recorded a novelty football song (even when Watford got to the FA Cup Final), he eventually learned to dress down, he went to Rochdale and held his tongue when he overheard the club’s directors muttering homophobic slurs. I remember him just being at the ground, a normal presence; I once got his autograph but it wasn’t a bit deal.

Watford didn’t even help Elton John’s musical career. His collaboration with Graham Taylor wasn’t based on music; Taylor’s favourite artist was Vera Lynn. While Elton had some big hits during his time as Watford chair, by the end of it he was creatively exhausted (in his autobiography he acknowledges that 1986’s Leather Jackets was a creative nadir).

Watford Forever is more of a football book than a music book. While that’s inevitable, it’s also a pity as there are important lessons here for anyone who is concerned with the culture of the music industry.

While I was reading the book, I kept thinking about Bodies Ian Winwood’s memoir from last year. Winwood castigates the sickness within the music industry; the lack of care that all too often leads to burnout and abusive behaviour. In exploring what Elton John found at his club, Watford Forever implicitly shows what he couldn’t find in the music world: Community, care, friendship, lack of pretension, purpose, self-discipline and home truths. In Graham Taylor, he found a friend who could and would say no to him; he returned the favour with unwavering support.

As a Watford supporter I am pleased he found all this at my club, but as someone who cares about music, I am sad that the industry couldn’t provide it. And in any case, while Watford did provide a refuge from the sickness of the music industry and help plant the seeds of a better life, he was only a part-timer in the real world, he still spent months each year mired in drug abuse, touring within the belly of the beast.

Working out how the music industry could provide a structure that cares is easier said than done. But part of the answer – or at least the diagnosis of the problem – may lie in the ways that musicians do or do not involve themselves in management and administration. Elton John, who had never worked in an office, had to learn how to chair meetings while at Watford. He had to worry about budgets and the difficulties in managing a bunch of young men. It’s not that musicians never do this stuff; many have ‘day jobs’ that require attention to the mundane. And underground musicians inevitably end up as their own administrators. In some music scenes, such as extreme metal, being dependable and well-organised is respected and esteemed.

Mega-stardom removes musicians from all of that. Once you have ‘people’ doing everything for you, then making music becomes all you do; that doesn’t just leave plenty of time to get up to mischief, it’s all too easy to become unanchored from the world, from the comforts of everyday routines.

At Watford, Graham Taylor insisted that the club didn’t refer to ‘fans’ but to ‘supporters’. He wanted to acknowledge the necessity of supporters to the club and the symbiotic relationship between those in the stands and those on the pitch. What would happen if musicians referred to their supporters rather than their fans? We do have some models for this, particularly when artists crowdfund releases, but once again it tends to be on the commercial margins of music. Maybe Lady Gaga’s Little Monsters, Taylor Swift’s Swifties or other communities built around stars do feel a close bond with the musicians they love, but what practical consequences does this have for the artists themselves?

I was struck by this passage in Watford Forever:

Although Graham tried to be as supportive as he could, it was his wife, Rita, who worked out what Elton needed above all – a sense of peace, of normality. After their experience at Rotherham, she suggested that Graham should invite Elton round to Mandeville Place for a family supper. It was an invitation he was a bit nervous about delivering, but which turned out to be gratefully received. There was only one rule, Rita told the two of them: they could talk about anything they wanted as long as it wasn’t football. Soon these suppers became a regular occurrence. Every few weeks, Elton would join the Taylors at their dining-room table – he was particularly fond of Rita’s shepherd’s pie, ideally followed by her rhubarb crumble.

We should see shepherd’s pie as a kind of metonym of the pleasures of everyday existence. It’s the least sexy food imaginable (and rhubarb crumble isn’t much sexier) and the Taylor’s were similarly stodgy in character. I don’t know where Elton John gets his shepherd’s pie now, although sobriety, marriage and children may mean he doesn’t need to leave home to get his fix.

Maybe this is what the music industry needs; to ask ‘the shepherd’s pie question’. If a star isn’t current getting their shepherd’s pie, their management and entourage need to consider where they might get it. They might even get it at a football club.

Watford Forever is out now via Penguin / Random House – find out more here