I don’t think I realised that the water in the toilet could freeze. Such a thing seemed impossible. But there was my older brother, in the flat he was squatting while he waited for council accommodation to come through, holding the wrong end of a toilet brush, breaking the ice. I was only ten, but I can still remember the intensity of the cold.

These moments in which the natural world intrudes on the facade of civility once the money runs dry are common absurdities of everyday life in the middle of every wealthy city in the world. Yet music about being poor, or at least hardly making ends meet, tends not to really capture small, brutal details like these.

Of course, this is due in no small part to the fact that the people who wind up in situations like this almost never get recording contracts at all. “The music industry is 80 per cent, 90 per cent privately educated”, said Sam Fender in a recent interview, and he’s right. Sam Fender is an eloquent man, but his music doesn’t exactly capture the underlying dread of life lived on the edge of destitution either. Let’s be honest, it just sounds like a Springsteen pastiche, filtered through five decades of Springsteen pastiches.

Fender’s style, the heartland rock sound so often associated with working class music, is half a century old, and representative of a completely different time, when working class people toiled predominantly in industry or were just beginning to be abandoned by it. The characters in ‘Allentown’ do not really reflect what it means to be poor today, where life persists under the threat of frostbite or a fiery death. Where is the music which represents that? Well, it does exist, of course, but you won’t see it on the BRIT Awards.

In the mid-2010s, something amazing began to happen in American hip hop. Much of this is charted in my new book, Songs In The Key Of MP3; specifically in the Earl Sweatshirt chapter, because Earl was the artist around whom much of it coalesced. He began rapping as a teenager, part of a group of kids called Odd Future, a collective who gained notoriety rapping about cartoon violence over Neptunes-worshipping beats. As he entered his early twenties though, the darkness of Earl’s music began to feel lived-in and true.

Earl spent most of 2014 hardly eating. He lost nearly three stone and, at his lowest, weighed only eight in total. He cancelled the final leg of his first solo tour out of concern for his health and the doctors told him to stay inside. He obeyed, embarking on a period of hermitic recovery. After three weeks of straight sleeping, he finally left the house to skateboard and immediately tore his meniscus. That made his leg atrophy, and he was confined to his bed again. It was there, dosed up on Vicodin, that he made his second album.

If 2015’s I Don’t Like Shit, I Don’t Go Outside sounds like a blur then that’s because it was made in one.The beats of tracks like ‘Grief’ trudge rather than knock; dense samples lingering like a waking thought. Earl’s voice, drawling and despondent, seems to drown in the density. The music feels heavy, literally heavy, like you’re being dragged backwards through the fog, and his rhymes spoke of resolute isolation: “I don’t know who house to call home lately / I hope my phone break, let it ring”.

Earl Sweatshirt pushed the headiness of that album further on his next: 2018’s Some Rap Songs. No other rap record sounds quite like it. At less than twenty-five minutes in length, Thebe and his collaborators sought to capture the sound of a waking dream. There are flashes of traditional tunes, but those snatches are so brief they sound like you’ve caught them while flicking between radio stations. Any recognisable instruments are looped into delirium, snakes eating their own tale. This is a hip-hop album – a genre dependent on language more than any other – and yet sometimes you can hardly hear what the rapper is saying. The one overriding sonic trait is the lingering hiss of white noise.

In the same period, Detroit rapper Danny Brown released Atrocity Exhibition, an album which filtered a similar mind state through a different narcotic. Rather than weed, its creator was on ecstasy when he made it, but the album contains nothing like the glorious mind-orgasm depicted in Kanye’s ‘Blood On The Leaves’. Instead, the album sees him alone in a bedroom which turns into a pit. “I’m sweating like I’m in a rave” he raps, “been in this room for three days / think I’m hearing voices / paranoid and think I’m seeing ghost-es”.

Across fifteen songs, Atrocity Exhibition veers between unvarnished mania and clattering chaos. On ‘Ain’t It Funny’ a squealing horn sample jump-starts an entire, spasming circus carnival and Danny somehow finds a pocket among it, rapping in a voice which sounds like the yelp Tom emits when Jerry steps on his tail. The album’s subject matter veers between trauma and the means he chose to deal with it. It feels like civility slipping, leaving Brown floating amid the cold waters of depression.

Some Rap Songs and Atrocity Exhibition are psychedelic music, just not as we tend to know it. Their styles seek to capture their creators’ mental states in song: Earl stoned on Vicodin in bed, Danny tripping on MDMA with the phone lines cut. Hip hop has engaged in psychedelia for almost as long as it’s existed. The Beastie Boys sampled a bunch of Beatles songs on ‘The Sounds Of Science’. In the 1990s Gravediggaz’ ‘Defective Trip (Trippin)’, Digable Planets’ ‘Time & Space (A New Refutation Of)’ and OutKast’s ‘Synthesizer’ all dealt in the consciousness-broadening effects of psychotropic drugs. After a couple of decades at the periphery, the 2010s saw a new generation of rappers engage in psychedelic culture. There was A$AP Rocky’s ‘L$D’, Chance the Rapper’s Acid Rap and, perhaps most obviously, Travis Scott, who hit the peak of commercial success creating paeans to the psychedelic on 2018’s Astroworld and 2023’s UTOPIA.

60s psychedelia is one of the most significant countercultural periods in modern history. The imagery of flower power and Ken Kesey’s Acid Tests are as prevalent today as they ever have been. But time has also worn away at the sheen of that specific, Californian moment. The hippy wave morphed into the rabid individualism of Silicon Valley, and the CIA’s role in the foundation of the movement has brought its very raison d’etre into question. The aesthetics of 60s psychedelic acts like The Zombies and the Grateful Dead are as popular as ever but, when listening to the music of a Kevin Parker or a Travis Scott, it’s hard to shake the feeling that they’re not really making psychedelic music at all. These new artists espouse aesthetic choices, first and foremost. Like Fender’s music, they are an emulation of an emulation.

From Woodstock to paganism, psychedelia has also long carried connotations of the pastoral: of rolling fields and flower chains and open skies. In films like Ari Aster’s Midsommar, it’s a connection which persists. Danny Brown loves that music (his favourite album is Love’s Forever Changes) and Atrocity Exhibition certainly contains many of the tenets of music as played by The Flaming Lips, from the back-tracked vocals to the swirling synths. What he and Earl Sweatshirt were engaging in, though, was of a different breed: psychedelia of the city. If psychedelic rock was born from trips taken in Bay Area mountains, these doom-laden records are instead inspired by the mind-altering, body-numbing effects of urban spaces.

This distinctly 21st century music is born of a type of lifestyle a great many of us are intimately familiar with. In 1960 30 per cent of the world’s population lived in cities. Now, more than double that do. In the mid-2010s, Earl and Danny began to subsume the things that kind of living entails: both the psychic stress of close confinement and the anxious retreat, an acute isolation only possible in a time when we’re constantly surrounded by people. Sure, the wooziness and mania of these albums were fuelled by weed and ecstasy, but they’re as much about falling low as getting high. Anyone who’s lived broke in a big city can also attest to the discombobulating stress of noise pollution or the stench of black mould. Depression and trauma are their own kind of out-of-body experiences too.

In Danny Brown’s early music, the derelict buildings of post-industrial Detroit were the stage his songs unfolded against. On XXX’s ‘Scrap Or Die’ he twists the chorus of Jeezy’s ‘Trap Or Die’ into a story about breaking into houses and stripping them of scrap metal to sell for cash. ‘Rolling Stone’ is a trip but, across the course of the song, Danny doesn’t move beyond the white glare of his phone: late nights on the Internet forging surreal networks of the lonely.

Around the same time those albums were released, FX debuted Atlanta, a TV show also masterminded by a rapper. With an ambition to be a Black Twin Peaks, the early seasons often depicted the surrealness of being poor and Black while trying desperately to make it out through rap. In the final scene of the first season, Donald Glover’s Earn – having spent the entire episode helping his cousin Paperboi flex on social media – retires to sleep in a storage unit. Across its seasons the show became increasingly bizarre, placing images of the surreal within the everyday.

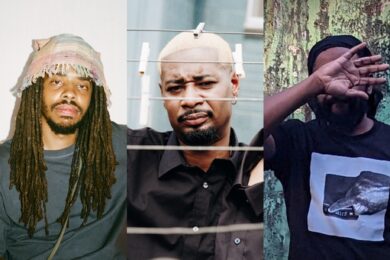

Earl Sweatshirt helped to craft the aesthetic of Some Rap Songs with teenagers like Adé Hakim and MIKE, the latter of whom channeled the headiness of that music into his own compelling records. While those artists baked surrealness into their production, other MCs channeled it into their lyrics. In the music of Billy Woods, for example, colonialism and liberal racism linger like ghouls, and his writing makes cosmic jokes about daily life in a society where power imbalances are a fact of living.

In 2019 Woods released Hiding Places. The album feels like a stroll through the rooms of a haunted mansion; the beats twitch and creak and Wood’s words turn violence, personal grievances and scenes of drug addiction into bizarre, fantastical dreams. On ‘A Day In A Week In A Year’ there’s a sense not of a higher power at work, but the lack of one: where fate doesn’t reside within the hands of the living but sheer, dumb luck. It’s a feeling we all know but the poor know most of all, and Woods captures it with a vignette of himself stood in an arcade, dropping cents into a machine. “Dollar movie theater, dingy foyer, little kid, not a penny to my name / fuckin’ with the joystick / pretendin’ I was really playin’”. Even the photograph on the album’s cover – a real red-brick mansion in Detroit – looks like something conjured by the Brothers Grimm. Urban decay, turned into a fairy tale.

What this wave of psychedelia and surrealism did was deploy the psychedelic and surreal to reflect a strange reality. After all, here’s young MC AKAI SOLO talking about a changing New York: “You always feel like you’re on acid when you’re walking down a block”, he told Okayplayer in 2021. “You have this side-by-side, split vision when you walk through places you grew up in that’ve been hit with the influx of gentrification… to watch it happen around you is a type of a slow push with the knife in the side.”

The presence of artists who can articulate such strange sensations is a reminder of what an outlier hip hop has always been. So much of the art people consume is made by the same section of the population, to an almost comical degree. EastEnders is written by middle-class people. The Sun is written by middle-class people. Often those people come from the same towns, sometimes the same schools. Not all of these artists are working class, but some of the biggest names in rap – Lil Wayne, Westside Gunn, Tyler, The Creator – began their lives poor. Hip hop itself, after all, was started in a project house rec room; a fundraiser so that DJ Kool Herc’s sister could afford the clothes for school. It’s no wonder this music alone has risen to the challenge of capturing a surrealistic reality.

Liam Inscoe-Jones is the author of Songs In The Key Of Mp3: The New Icons Of The Internet Age, which is out now via White Rabbit