-"Doctor… why do you always show the greatest interest in the least important things?"

-"The least important things, sometimes, my dear boy, lead to the greatest discoveries."

Fifty years, then. Well – sort of.

Certainly, it’s fifty years since the 23rd of November, 1963, the day the very first episode of Doctor Who went out (the day after John F Kennedy, CS Lewis and Aldous Huxley died, a fact so perfectly, breathtakingly symbolic that I have to mention it here, but also one I’m going to skip over on account of my conviction that two of them were idiots).

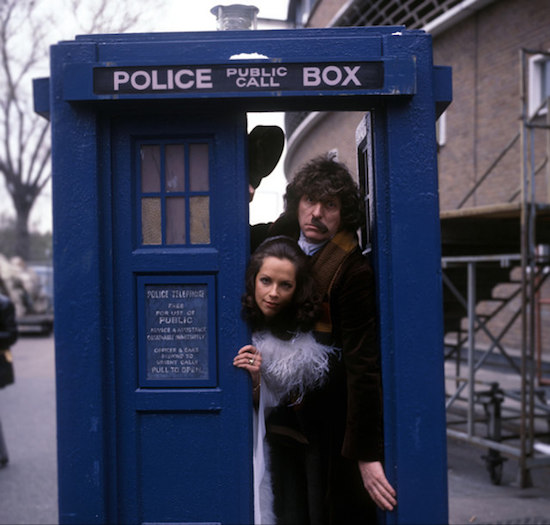

But it feels a little dishonest to do this, you know – "fifty glorious years" and all that. Because those years were not all glorious, because there weren’t really fifty of them (there were two whacking great gaps in the middle, one either side of that TV movie with Paul McGann in it which nobody liked) and also because Doctor Who is not in fact a continuum but a sequence of very different programmes, some of which have very little in common with the others except for the central character’s name – or lack of it – and the box where he lives. Arguably, the programme which has called itself Doctor Who since 2005 is something else entirely: a 21st century spectacle which doesn’t, and couldn’t, recapture the texture and tone of the original show in any of its incarnations, all of which now seem inextricably tied to a particular time, a particular world, a particular way of doing things. There’s no reason why you should like one version of Doctor Who, just because you liked another. (I suppose it’s childish to say that anyone who prefers the later incarnation of the show is an imbecile, so I shan’t, although it is what I think.)

Between 1963 and 1977, with Doctor Who at its lurid, improbable best, no one – no one in their right mind anyway, no one over the age of twelve – would have called it the greatest television programme ever made. Doctor Who? You’re joking, right? It’s a programme about a man who travels through time and space in a telephone box. The eight year olds enjoy it, but…

These days, now we’ve seen what happens when you undervalue certain things, those things to which old Doctor Who is inextricably tied, like generosity and human decency, a sense of endless possibility – now we know what we’ve lost – it doesn’t feel foolish to say it, or at least to say something like it.

The greatest television programme ever made? Perhaps.

‘An Unearthly Child’ (1963): Ian and Barbara, the first companions, encounter an undomesticated Doctor

When I say Doctor Who, I’m usually thinking of what’s now called "the classic series", which began with William Hartnell kidnapping teachers from a London junkyard and finally fizzled out, creatively, somewhere inbetween Peter Davison being attacked by a giant chicken and bubble-permed Colin Baker hurtling downhill on a runaway gurney, like some kind of cosmic Compo – yes, it was a slow and lingering death, and it’s hard to pinpoint exactly when the light went out. But this is the programme I’m here to praise, the one whose anniversary I’m trying to celebrate, even as it’s being pushed to the side of its own legend.

There are still a lot of people who turn up their noses at Doctor Who – this Doctor Who, the real Doctor Who – or worse, consider it some kind of quaint precursor to the modern show. Proper science fiction fans have never liked it much, what with its jolly disregard for what science fiction "should" be, and its stubborn refusal to be totally po-faced. Mention it in polite company and soon you’re smiling patiently at those fifty-year-old gags about Daleks and staircases, and of course they’ll assume you’re one of them, a Doctor Who fan, one of those long-scarved middle aged perverts who make Comic Book Guy from The Simpsons look like Jimi Hendrix at Monterey. It’s like most National Treasures, really: fondly remembered, as a bit of a joke.

This, I think, is the result of a misunderstanding of how popular culture works, and an even deeper misunderstanding of old Doctor Who. Old Doctor Who – the real Doctor Who – is beautiful, just the way it is. People imagine that you’re going to want to apologise for it, or try to pretend those monsters didn’t actually look that bad, and who knows, maybe there are alien planets that really do look like that. Well, no – that’s not the point. Doctor Who is like pop music: it’s cheap, loud and trashy. And, as with pop music, these are not flaws but strengths – adding power and immediacy, validating everything. Enabling, from time to time, a peculiar transcendence, a particular kind of truth.

And, as with pop music, trashiness is a hook, a way for Doctor Who to communicate big ideas without having to bore you; to encourage absolute mental freedom, with all those crazed audio-visual freakouts, all those mind-expanding trips into the abstract, and the absurd, and the extreme. If we are to accept that low culture can have genuine worth – and at this point, I’d say we have very little choice – then we must recognise Doctor Who, this Doctor Who, the real Doctor Who, a programme about a man who travels through time and space in a telephone box, in the same way that ‘Tutti Frutti’ is a nursery rhyme about fucking.

Old Doctor Who is rude. It’s gaudy and brutal, and instinctively hostile to any middlebrow notions of "good taste". Pick a few moments at random and see. Jon Pertwee is stranded on an abandoned sea fort, and a scaly Sea Devil peeps from behind a rusted girder; the analogue synth starts squealing like a dentists’ drill, and the camera crash-zooms into the monster’s trembling rubber face. Tom Baker wakes up on an operating table, and a surgeon brandishing an outsized syringe moves slowly towards him; scrambling clear, he hits a wall of smoke and machine-gun fire, from which emerge a soldier and his horse, both their faces hidden by gas masks. William Hartnell hobbles across the steel floor of the Dalek city, to the bleak shimmer of Tristram Cary’s atonal electronic score; a Dalek fires on its victim and the monochrome screen begins to flash, white to black, white to black, the living room erupting. This is raw, crude television – retina-scoring, eardrum-rending – and it is not easily ignored. Originally intended to educate children in history and science ("No bug-eyed monsters!" its chief creator Sydney Newman instructed, in vain), Doctor Who soon learned that you could also teach the kids a thing or two with flash and sensationalism; put over your points and your parables with noise and light and the power of full-on British weirdness. Stretch the imagination to breaking point and people will listen, and they won’t forget.

Unlike most mass-market sci-fi, old Doctor Who would rarely resort to soppiness or sanctimony; there was no need. But it was righteous all right. Just below the surface you’ll find pretty much everything that’s good about humanity, everything worth preserving from the latter half of the 20th century, with its half-forgotten ideas about equality and compassion. This is a programme about tolerance, morality, humanism and nonconformism, about the balance between responsibility and individualism… a programme about escape. It’s a celebration of the outsider, the trickster; a jibe at authoritarianism, militarism, patriotism and the cult of violence (all those sci-fi heroes with their ray-guns and their military titles, all those superheroes thumping people – Tom Baker used to call them "boneheads"). And somehow – as with pop music, eh? – none of these things are undermined by the fact that so much Doctor Who was hacked out under pressure by men with money on their minds. It’s not precious about things like that; it is what it is.

And at its worst, it’s like most things: it’s lousy. When leaning too far one way or the other, into simple silliness, or mirth-free nerd-service, it can really try your patience. And in those unfortunate moments when money, time and inspiration run out simultaneously, it really is just bollocks built from Bacofoil and B-movie clichés ("I’m qualified in space medicine," announces a dashing young rocketship pilot). When the lead role is played by Colin Baker (who’s simply a bad actor) or Sylvester McCoy (who’s not even that), it’s practically unwatchable.

In almost every story, though, there’s something. Something to make you laugh; something to startle or gently disturb. Something unselfconscious and thrilling. It’s not trying to sell you anything. It wants you to be scared, and then it wants you to be happy. And then it wants you to be free.

‘The Silurians’ (1970): The Silurian plague hits London – or Marylebone Station, at least

Doctor Who could probably only have been made by the BBC as it was in the 60s and early 70s; all its strengths and weaknesses seem to correspond to those of the Corporation in what were, and look increasingly likely to remain, its glory days.

Those strengths were only made possible by that amazing, never-to-be-repeated freedom in programme-making – one which included the freedom to make mistakes, the most important freedom of all. ("Make mistakes and confuse the enemy!" grins the Doctor, midway through a story which pits the Daleks against some rather disappointing-looking aliens in disco wigs.) And the weaknesses? Well, sometimes in the early days you do get the feeling that the Beeb’s falling back into bad old habits, broadcasting exclusively to the sons and daughters of the privately-educated classes… or maybe it just looks like that from a fifty-year distance, and what we’re really seeing here is only a refusal to dumb things down. Whatever, this is a programme which seems to take for granted that ten-year-old children are familiar with Catherine de’ Medici’s persecution of the Huguenots, or at least that they’ll want to sit there on a Saturday teatime and learn about it.

By the 1970s that slight stuffiness has gone, but Doctor Who makes one or two of the decade’s usual mistakes. It can be decidedly sexist, sometimes gleefully so. It’s passionately anti-racist, in theory – in practice it can be a bit… clumsy. ‘The Talons Of Weng-Chiang’ is one of the finest Doctor Who stories ever, a fabulously witty pastiche of Sax Rohmer and Conan Doyle, set in that foggy Victorian London of gaslamps, music halls and hansom cabs. It looks gorgeous, even today (apart from the giant rat, but let’s not worry about that for the moment). Every line of the script just sings; the cast are all superb. And, with depressing inevitability, its "inscrutable" Fu Manchu-like villain is a white bloke with the corners of his eyes pulled back with bits of sticky tape.

Also – let’s not beat around the bush – to the modern eye, old Doctor Who can look a little bit tatty. Exteriors on filthy 16mm film, interiors on videotape; mostly shot on three-sided sets which are draped with bubblewrap and lit like an autopsy. Very rarely, when watching Doctor Who, does it slip one’s mind that these are not in fact aliens on faraway planets, but real people in a real place. And yet, that place – post-war, pre-Thatcherite Britain – now seems more distant than Gallifrey or Skaro; a place where some things were more important than how much fucking money you’d spent.

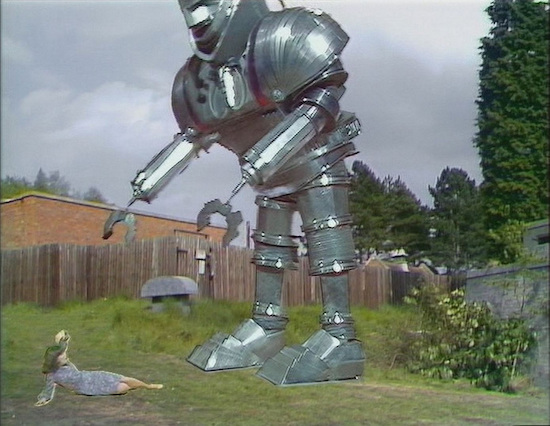

Anyway, Doctor Who doesn’t give a toss about your lack of imagination. The Doctor and Sarah Jane Smith get back from the Middle Ages, and find the streets of London deserted – the city is infested with dinosaurs. These have been summoned, so it transpires, by loopy eco-idealists bent on returning the Earth to its ‘Golden Age’ before the dawn of man. It’s a great idea, but it’s a great idea in which people are attacked by prehistoric lizards. Could the BBC’s visual effects department, in 1974, construct convincing animatronic dinosaurs on a Fingerbobs budget? Astonishingly, no. But hey, who cares – they made some unconvincing ones instead. It looks hilarious. But it doesn’t matter. ‘Invasion Of The Dinosaurs’ has real pizazz, and something to say, and it doesn’t treat you like an idiot. Yes, you’ll laugh at the special effects – but that’s just another way in which the story brings you pleasure.

Here’s a fact too often forgotten: you were never actually meant to look at a washing-up liquid bottle sprayed silver and confuse it with a real spaceship. Rather, you were meant to understand that this was a representation of a spaceship, to tell you that the following scene was going to be set on a spaceship. It’s probably impossible to get back to that way of thinking now, and if you ask me that’s a bit of a shame. If someone flips you a 50 pence piece and says "there’s your visual effects budget, mate" you’d better make sure that your story is good. If, on the other hand, CGI has dropped in price to the point where you can remake Jurassic Park on your mobile, there’s suddenly a strong temptation to slack, to think "sod it" and just make ‘Dinosaurs On A Spaceship’. If Chris Chibnall, author of that particularly noxious new-series no-no, had been informed that his story was going to be shot in a day in a studio the size of my kitchen, with three glove puppets and a packet of sparklers, he wouldn’t suddenly have turned into Dennis Potter (or even Malcolm Hulke). But who knows? Maybe he’d have tried a bit harder.

People worry too much about special effects – give me the fearlessness of old Who any day. There’s nothing to be embarrassed about; the brashness is part of the appeal. Even when this bold approach backfires – as in 1965’s ‘The Web Planet’, in which the Doctor lands on a world inhabited by various species of alien grub, a bizarre and elaborate allegory for communism, or cancer, or both – what ends up on the screen is always thrilling in its way. The battle scene at the end of episode four, in which men dressed as giant wasps swing back and forth on Kirby wires past two-dimensional scenery and a badly-painted backcloth may look like one of Ed Wood’s fever dreams, but soundtracked with electronic bleeps and the music of Les Structures Sonores, it is at least very intense television. Earlier in the story, a Zarbi – a man-sized ant with the legs of a man – comes charging round a corner and barrels straight into the camera: THUNK. Did they edit this out? They did not. (Until the DVD release in 2005, that is, on which the noise of the collision was muted: this bizarre masturbatory shame is one of the least appealing traits of the modern Doctor Who industry… of which, more later.)

I don’t want to mislead anyone. The average Doctor Who adventure is not a breathless white-knuckle ride. Most of them in fact progress at what you might call a leisurely pace; for what is ostensibly a children’s programme, there are an awful lot of scenes in which men in their forties stand around talking. The early black and whites, especially, are best watched in a kind of meditative state, tuned in to the atmosphere rather than waiting around for the action.

But make no mistake, those episodes are wonderful. The William Hartnell stories in particular have a marvellously eerie distance, and since the programme had not yet settled, it is at this point impossible to predict. Hartnell careens, seemingly at random, from experimental theatre weirdness (‘The Edge Of Destruction’) to comic-strip thrills (‘The Dalek Invasion Of Earth’); from pitch-black period drama (‘The Massacre’) to chortling Carry On-style farce (‘The Romans’, ‘The Myth Makers’, ‘The Gunfighters’).

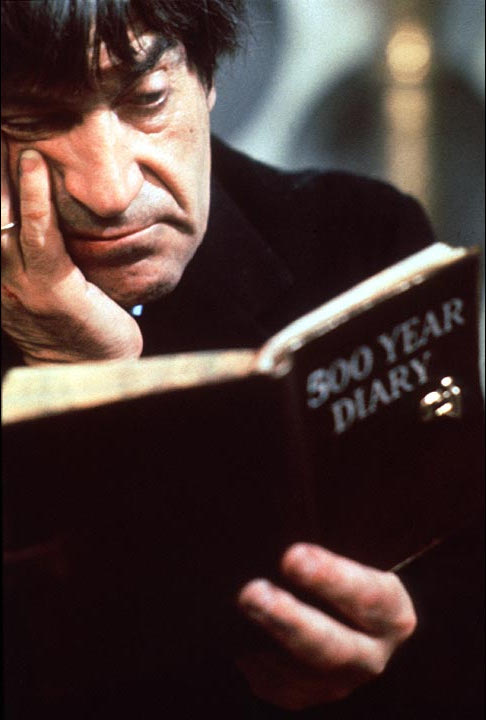

And then, the beguiling performance of Patrick Troughton, whose facial expressions alone give the character vertiginous depths not always present in that era’s scripts, in which he saves space-suited humans from monsters with ray-guns, week after week after week. Troughton is by quite some distance the best actor to play the role, and when given something he can really have a go at – an LSD fantasia by the creator of Crossroads, say, or a Dalek story pondering the nature of humanity – he’s absolutely bewitching.

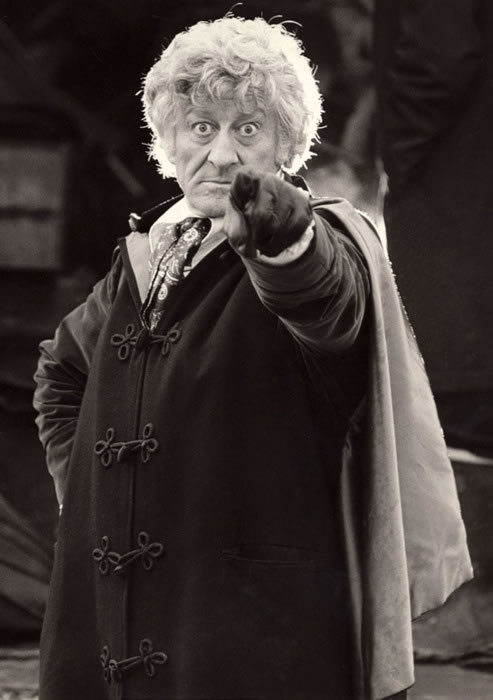

When we move into colour, with the lead role passing to Jon Pertwee – who comes over as a cosmic hybrid of Alvin Stardust and Margaret Rutherford – that’s when Doctor Who begins to push… and things start getting nasty. In ‘Spearhead From Space’ the evil and incorporeal Nestene Consciousness invades Earth via plastic, which it somehow inhabits and animates; in a department store on Ealing Broadway, the shop dummies twitch, stiffen and walk out into the street. ‘Terror Of The Autons’, a sequel from the following year, escalates these pulpy chills beyond all reason, and is wonderfully irresponsible. A man sits down in a plastic armchair; it swallows and asphyxiates him. An artificial daffodil spits a bolt of liquid plastic into the face of poor Jo Grant; it seals into a film over her nose and mouth, and she staggers round the room, suffocating. Rescued from malevolent circus folk, our heroes are riding in the back of a police car; suddenly suspicious, the Doctor leans forward and rips the skin from a bobby’s face, revealing a featureless plastic skull. Questions were asked in Parliament, or so the story goes. A few years later, with Tom Baker installed as the Doctor and ready to give it everything he’d got, the author of these modern nightmares – a genial, supremely talented hack named Robert Holmes, who said the secret of good Doctor Who was to walk the line between "Grand Guignol gothic horror on one side and Monty Python on the other" – took control of the programme’s scripts, and for several glorious years this is just what Doctor Who became: an exploration of the darkest corners of the pre-teen subconscious, an absurdist video nasty with your fish fingers and chips. Only through the tireless campaigning of Mary Whitehouse were Britain’s children finally freed from Holmes’ grasp, and again left to stumble towards adulthood, totally unprepared.

‘The Claws Of Axos’: It’s 1971, and if you turn on the telly at teatime, this is what you see

Most of the cleverest, funniest, most creative people I’ve ever known have turned out to be Doctor Who fans. I say "turned out to be", because often I’d only discover this some time after meeting them. Things were different in those days. We were like gay men in the 50s: we had to feel completely secure before we could risk being honest with each other.

(Crotchety. Roundel. Pseudo-historical. Base under siege. Cartmel Masterplan. Classic Holmesian double-act. Canary yellow Edwardian roadster. What? Oh, nothing. Don’t mind me.)

But the media, and most of the general public, have a very particular idea of what "Whovians" are like (and by the way, no British fan would ever refer to themselves as a "Whovian" – it’s an American term, generally considered a bit of an embarrassment even by people with pictures of themselves dressed as K-9 on their Facebook page). In fact, Doctor Who fan culture – "fandom", as you’re meant to call it – is quite a curious and complex thing. It’s still dominated by the worst people in the world, as the internet will confirm in short order, but that’s never been the whole story, and most of the stereotypes are badly out of date (since the new show changed the mood of fandom, the sourness, pedantry and psychotic lack of perspective have been overtaken by something almost as bad: a twee, complacent whimsy). But Doctor Who fans aren’t a homogenous group. Some of them have a sense of humour. These days, there are even some women.

The public image of Doctor Who fans may be only one rung up from that of vivisectionists, but the media give credit where credit’s due. It’s often said that the new series’ greatest strength is that it’s entirely the creation of lifelong Doctor Who fans who’ve gone on to work in television. And I’d say that’s its biggest problem.

Long before the programme’s return, longer still before he took charge of it, Steven Moffat gave a now-notorious fanzine interview in which he killed the thing he loved: Doctor Who was "shit," he said, and everyone responsible for making it should have been "clubbed to death". He was clearly on a wind-up – not insignificantly, the interview took place in a pub – but there’s no mistaking that peculiar shame which settled over so many otherwise intelligent and well-adjusted Doctor Who aficionados, back in what fans call "the wilderness years". Working in the airless world of television, in the 90s, nursing an unironic love of Doctor Who… it can’t have been easy. Were he to show this terrible old programme to "my friends in television", Moffat said… well, they’d laugh at him, like his mates used to. ("What I resented was having to go to school two days later, and my friends knew I watched this show. They’d go ‘Did you see the giant rat?!’ and I’d have to say I thought there was dramatic integrity elsewhere.")

However many awards they give you, this kind of shame is a lifelong condition. New fans won’t understand this at all, but those of us past a certain age can recognise it instantly – nothing will ever erase that stain. Which is the problem with entrusting this particular show to "fans who’ve gone on to work in television". Hopelessly devoted to the programme and its history, but still resentful of what it did to their early adult life, these are the lost generation of Doctor Who fans: middle-aged men with a beef.

So New Who is brimming with worshipful fan-wank – endless back-reference, monster supergroups, all that wish fulfillment crap – but strangely keen to distance itself from the programme it purports to be. Count the wearying post-modern jokes at the show’s own expense; witness the flipness. It’s as though its makers lack the courage of their own convictions, still feel some vestigial need to prove they’re cool to weans in Paisley, or television professionals of fifteen years ago. So they make the Doctor attractive to women, even allow him to cop off with them, because this is modern television (i.e. working to the agenda set by the advertising industry which has still managed to infect the BBC). They turn the programme into a joke, in order to prove they’re not humourless obsessives; fill it with gags about sex, in order to prove that they’re no longer virgins. It’s a bit peculiar, really. Then again, whenever fans have been allowed near Doctor Who, they’ve always made a mess of it.

Still, the general perception – certainly outside fandom, and to some extent within it – is that this new show is just inherently better than the old one, with its "wobbly sets" and its "running down corridors". Well now… aside from the fact that cheapo CGI is the wobbly set de nos jours, and aside from the fact that the new show features loads of running down corridors (it’s just that rather than being there to pad out stories which are much too long, corridor chases are now required for breathless info-dumps, because the stories are much too short)… aside from all this, when you actually sit and watch these programmes, you notice something quite surprising. The old series is objectively superior to the new one, on almost every count.

‘Tomb Of The Cybermen’ (1967) – The Cyber Controller Awakes. YOU BE-LONG TO UZZZZ. YOU SHALL BEEE LIKE UZZZZ.

The new show is unrecognisably slick by comparison, of course, but that’s to be expected. Things have moved on considerably since the days of multi-camera production, when Doctor Who was made in practically the same way as Top Of The Pops. But let’s not kid ourselves – it still looks cheap. Just because you can fashion an alien world on a laptop now, instead of having to spray-paint polystyrene, it doesn’t mean it looks like anything other than what it is. The monsters of today might not have zips down the back, but they don’t look any more "real" than the Yeti or the Taran wood beast.

What the old show had, most of the time, were stories which made some colour of sense, had something to say, and were given some space to breathe and develop (compare ‘The Silurians’ from 1970, creaky and slow as it seems today, to the torrent of tartrazine vomit that is ‘The Bells Of St John’ or ‘The Runaway Bride’). Characters who spoke like people, or at least dramatic representations of people, rather than refugees from a freshly-axed sitcom on BBC Three. That unearthly electronic music, which prised open so many millions of minds, instead of this tacky orchestral gloop; it’s striking, too, how much silence there was in old Doctor Who, something that’s now entirely forbidden, which is why, however hard it tries, New Who can never be tense. Even in terms of acting – not really Old Who’s strongest suit – the new show falls on its arse, really, once you get past those big-name guest stars. It’s as hammy as it ever was, it’s just that these days everything’s pseudo-naturalistic and soapy (sub-Shakespearian bluster having long since gone out of style). There are performances in the old series just as bad as those salvage men from ‘Journey To The Centre Of The Tardis’, yes… but only about four. Maybe three.

Worst of all, I think, is what’s happened to the character of the Doctor himself. He’s meant to be unlike anyone you’ve ever met – not the kind of hyperactive, squealing young prick you’d change pubs to avoid. All three new series Doctors have been played by decent actors; that’s not the problem. The problem is what they have to say, and how they’re expected to behave. There’s nothing to suggest that Peter Capaldi will be spared this identikit "new Doctor" dialogue; even regeneration, it seems, can’t stop this infinitely wise thousand-year-old alien talking like the wackiest fucking bastard in the union bar.

(Neither was the old Doctor a "lonely god", or "the oncoming storm". And never – not once – would he ever have dreamt of announcing "I’m the Doctor", as though it were meant to be some kind of threat. This is partly celebrity culture projected into the stars, and partly a kind of perverted machismo for geeks. Hi, what do you do? "Look me up.")

It’s strange. We’re always being told that Doctor Who, as it is right now, is clever and sophisticated – yet it breaks so many basic rules of drama, and doesn’t seem to be doing it deliberately. A universe in which things become possible just as soon as they become convenient. The ontological paradox: an answer to every question, and the question for every answer. All those central characters that don’t seem to have characters. I mean, they have characteristics; they have things that they do (you know, those things that they do). But they don’t seem to think or believe anything, and are kind of hard to pick out in a universe where everyone, but everyone, is preening, smart-arsed and a bit of a dick.

Dennis Wilson – ‘River Song’On balance, I’m glad New Who exists. If it didn’t, the space would only be filled by something worse. I just wish it wasn’t the way it is: superficial, sneering, flippant, sentimental, incoherent, irredeemably smug.

Why do I still watch it, then? Well, it is – or claims to be – Doctor Who, and God knows I’ve sat through some crap in my time, just because it called itself Doctor Who. And besides, you need only watch the first half-hour of ‘The Time Of Angels’ to see how brilliant Steven Moffat can be when he tries: it’s dense, involving, perfectly weighted, highly inventive, genuinely funny. It also features a staggering performance from Matt Smith, before whatever happened, happened (all the subtlety was battered out of him, or something went to his giant head). There’s always the chance that something like this will happen again, I suppose, just like there’s always the chance that the next Rolling Stones single will be as good as ‘Gimme Shelter’.

Nothing’s likely to change – not soon – because you don’t mess with a profitable formula, which this one still is. Besides, when the very same people who think of the old show as embarrassing kitsch are served up something like ‘Journey’s End’, or that "stirring" speech from ‘The Rings Of Akhaten’ with the big soupy music and the little girl singing – by some distance the kitschest moment in the history of Doctor Who – they seem to mistake it for King Lear at the National. I dunno… it’s like most things, I suppose. Certain that because it’s moving, it must therefore be moving forwards.

"It’s only Doctor Who," people say to me, rolling their eyes. "It’s a programme about a man who travels through time and space in a telephone box. As long as the eight year olds enjoy it, that’s fine. Why don’t you lighten up?" It’s not polite to tell these people they’re the reason this country is turning into a putrid swamp of philistinism and wilful ignorance, you know, so I usually just shrug and say that when Doctor Who is good, the eight year olds enjoy it but there’s something for the grown-ups too, and what’s more both of them can get something out of it, something surprising, something worthwhile. And I sound like one of those long-scarved perverts, so I shut up and I go away and I think about something else instead.

Anyway, in one sense Doctor Who is just what it always was: a reflection of its time. We grew up watching a hero who arsed around, but came through victorious because of his sheer generosity of spirit, and thrilled to a series which was threadbare and creaky but made us feel very, very alive. Now we sit and stare at a hero who acts like he’s trying to sell lager to wankers, alternately confused and depressed by a series which is – despite its good intentions – spiritually fucked. People say it’s just because we’re not kids any more, but I’m not so sure that it’s us who’ve grown old and cynical.

Old Doctor Who is still around, anyway – every story’s on DVD, and they’re still selling, modestly but steadily. And it’s still what it always was: vulgar and thrilling, thoughtful and shiny and creepy and silly and free. The kind of thing Britain used to do well. And, unless a lot of impossible things start happening soon, may never be able to do again. This is how I feel about Doctor Who at fifty: relief that it’s still around, but also sadness at what’s no longer possible. I suppose that’s what fiftieth birthdays are like.

And so, in another fifty years, if by some miracle our children are not preoccupied with resource wars or extinction events, or alien invasions – what will Doctor Who mean to anyone? Will it be remembered at all? Well, you know, I’d like to think so. Even if it’s only students of ancient history or primitive forms of communication sitting there watching that Dalek rise from the Thames by Hammersmith Bridge, or Davros trembling in his bunker, screaming about a power that would set him up above the gods, I’d like to think that they’ll still get something from it, that it might do more than simply make them laugh, that they might even notice what’s just below the surface: pretty much everything that’s good about humanity. Maybe, too, they’ll appreciate a glimpse of a very different time, when it didn’t matter how much money you spent, when you could arse around and come through victorious, when possibilities seemed endless. Then what will they think of Doctor Who?

The greatest television programme ever made, perhaps.