For this feature, we set our writers a brief: write about the most disturbing music you own, or have ever heard. The responses were varied. ‘Disturbing’ is a broad term, and the resulting 40 pieces of music, compiled below, plumb all manner of darkness.

Some, like David Bennun’s childhood terror at the hands of The Beatles, or John Doran’s tales of driving round Bristol in a van, on the edge of a Residents-induced breakdown, are darkly comedic stories. To be clear, however, there is subject matter below that is genuinely upsetting. Some of the disturbances are specific to the writer, a break-up, a bad trip, the loss of a relative or worse. Others tackle some of the most profoundly awful truths of our society and history and the subject matter does not make for easy reading.

Aaliyah – Age Ain’t Nothing But A Number

If Jimmy Savile has taught us anything, it’s that sometimes abusers hide in plain sight. Nothing has been proven about R Kelly, who wrote and produced Aaliyah’s first album in 1994, when she was just 14. But it’s impossible to read more allegations against him (Jerhronda Pace being just the latest) and not make some pretty gruesome connections regarding this album’s subject matter. On the surface, Age Ain’t Nothing But A Number is all sparse yet bouncy 90s R&B: New Jack Swing for your jeep, just like the intro says. But by the eponymous track 4, as the teenage Aaliyah tells in her diary that yes, age is just a number, we have to be concerned.

These lyrics were written by Kelly, for the woman who would become his child bride when he married her illegally in August 1994. Her parents soon found out and it was annulled by 1995. Afterwards, according to the Chicago Sun Times, she wouldn’t even say his name. She moved on to greater success in both music and film, before dying in a plane crash in 2001. If she’d lived, she might have had a lot to say about R Kelly’s recently recurring legal problems.

Manu Ekanayake

Alternative TV – Vibing Up The Senile Man

The year is 2015. Dwindling coalition. My relationship is on the rocks. The nagging sense that work and romance are about to crush me like rush hour crowds. The Reginald ‘fuck it all I’ve just about had enough” Perrin vibes. Total fucking brain disturbance.

Chatting over Facebook:

“I ordered that ATV rekkid after you posted that grimm song”

“Suffer the agoneeee diiieee”

“Cunt full of 5 watts which powers nothing at all”

“Negative wattage in reality”

“This needs to be played very loud so that the hair on your neck stands up”

The terror is in your radio….oh oh… it’s like if the Doors lived in Deptford and ONLY took acid and speed. Blank descriptions of romance hitting the tracks. If there was a romance. It’s the ramblings of some paranoid, possessive, therefore normal bloke stunned into his armchair. His shitty, lonely pointless armchair. What rhymes with armchair? Despair.

Facebook again:

“It’s playing I’m not crying

“But I am deeeaad inside”

“Dead flowers, dead mini aubergine cunts.”

The day that followed was traumatic. A man collapsed after staggering through the A&E entrance. He turned a frightening shade of darkening blue. Everyone arrived. CPR on the floor. A mixture of emotion swept through the waiting room, nonplussed to impatience. “Is it going to be much of a wait?” Just me, the arsehole, deciding who gets priority. Later in the pub a turgid phone break up. Next day a vodka bender, playing this record to anyone I could trap.

Lisa Lavery

The Beatles – ‘I Am The Walrus’

I wasn’t the first child to be obsessed with The Beatles, I should think; not by a long chalk. But there can’t have been that many ten-year-olds fixated on the minutiae of the ‘Paul Is Dead’ myth, which I had read about in a cheap paperback biography of the band. I took it very seriously indeed. It superseded all other, more traditional ghost stories.

The Beatle Death Clues led me inevitably to ‘I Am The Walrus’. It had always spooked the Bejesus out of me anyway, with its sliding strings, sinister funhouse backing vocals, surrealist (in the true sense) imagery and wordplay, and all-round atmosphere of dis-ease. Added to that for me was the sense that it was a doorway into horror. “Oh, untimely death” exclaims one voice in that long, pulsating climax to the song, amid the eerie chants and whoops “Bury my body” gasps another. Both quoting Shakespeare, I now know, but I didn’t then.

The Blue Album was frequently on the family record player; I would sometimes flee the room when side one ended, before the disc was flipped. Over time I steeled myself to stay. And listen.

Guess what my favourite Beatles song is now. It still creeps me out. It’s terrifying. It’s magnificent. I barely hear the “clues” any longer. I do hear the ingenuity and the humour. It was my first lesson in how great pop doesn’t always make you feel good things. And how sometimes it refines, exquisitely, the awful ones.

David Bennun

Beherit – Drawing Down The Moon

The preposterous spawn of three Finnish men with silly names and a plague-cart full of powerful hallucinogenic mushrooms, Drawing Down The Moon might be considered too preposterous to be anything close to disturbing. And yet Beherit’s second album sounds like what would happen if man and plant started mating and it scares the fuck out of me. The work of musicians that have taken so many drugs they’ve basically turned into separate life-forms, Drawing Down The Moon has a bare wire of stark madness crackling and swaying over it throughout and a desperate and unstable grandeur that constantly threatens to collapse into mulch. It’s music made by men who have come back from somewhere a long way away and have come back altered. And it’s embrace of the fungal and post-human disgusts and fascinates me.

Mat Colegate

Butthole Surfers – ’22 Going On 23′

Soundtracking the dawning of your first acid trip with your first listen to Locust Abortion Technician is a bit like starting an English literature course with Finnegan’s Wake. While it’s definitely worth going there, you should probably build up to it. But I was a daft teenager in someone else’s room at university. Everyone else seemed to be enjoying it and I didn’t understand what we were getting into until it was too late.

The climax of my increasingly eviscerating descent into distress and discombobulation was the final track, ’22 Going on 23′. Its combination of thunderous drumming, arcing, howling guitars, mooing cows and a recording of a phone-in in which a woman describes being sexually assaulted REALLY freaked me out. Was the call real? If so, were we supposed to find it funny? I didn’t have the psychological equipment to deal with my surroundings. Off down a long, dark tunnel I went. Meanwhile, my fellow psychonauts decided to listen to Big Black, the fucking idiots. It was time to go.

The rest of the night wasn’t much more fun – how could it have been after that start? It was one of those terrifying trips where you genuinely aren’t sure you’re coming back. And maybe I didn’t. Soon, I became markedly more enthusiastic about both LSD (no subsequent experiences were remotely as harrowing) and Locust Abortion Technician (it’s one of my all-time favourite albums). But I have wondered about the extent to which – rather than my perception of the music and the drugs changing – the music and the drugs changed me.

Phil Harrison

Carl Orff – Carmina Burana

The exact truth of Carl Orff’s relationship with the Third Reich will never really be fully known, and it’s probably best to side with the Canadian historian Michael Kater and see him as existing in a “grey zone” rather than in black (collaborator) or white (resistance fighter) terms. I see it as a pretty dark shade of grey though. Even if he didn’t work directly for the Nazis – and there are enough people with enough evidence who claim he did – he was definitely quick enough to write new music to replace (the Jewish composer) Mendelhsson’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream score with a more Aryan-friendly piece of music. And he was quick enough to switch back when it was all over. His claim during post-war denazification processes in America to have been a founding member of the White Rose Movement has been thoroughly debunked. In fact it seems likely that he could have intervened in his friend (and actual WRM founder) Kurt Huber’s execution in 1943 but instead begged Huber’s wife to leave his name out of it lest it harm him.

Orff, who had a Jewish paternal grandfather, had the luxury of abdication of certain moral issues by the fact Carmina Burana, his astounding cantata first performed in 1937 won the extreme affection of just enough high ranking Nazis to essentially make him ‘one of them’. And then he proceeded to cut his creative cloth accordingly, whether essentially pro-Nazi during the war or essentially anti-Nazi after. One can’t help but presume it is nothing more than fashion that has seen Richard Wagner become the go-to Nazi composer for pub bores to hate and not Orff, Richard Strauss or many others besides. I don’t find Carmina Burana disturbing because of ‘O Fortuna’ and its association with cinematic horror. (Like many people I’ve grown up assuming that I first heard this track when watching The Omen only to find out as an adult it actually doesn’t feature anywhere in the film. Also like many other people I was appalled rather than disturbed by that scene in Oliver Stone’s The Doors).

Likewise any terror it once held over me as a pre-teen because of all of its thunderous warning of the madness of adulthood to come (yeah, thanks Old Spice) has faded completely. I find this music disturbing because it reminds me that no matter how good it is, art (and by extension life itself) is most often mired in compromise while serving as a reminder that few among us can truthfully claim that we would have the mettle to do the right thing were we unfortunate enough to be in the same situation.

John Doran

Circuit Des Yeux – ‘Paper Bag’

Circuit Des Yeux’s ‘Paper Bag’ is named after a line from the peerless Joan Didion, in her 1961 essay ‘On Self Respect’‘: “It was once suggested to me that, as an antidote to crying, I put my head in a paper bag.” Haley Fohr’s music, among other things, explores the danger of erasing yourself and your feelings. As Didion warns, if you’re not careful, you’ll disappear entirely: “One runs away to find oneself, and finds no one at home.”

Anna Wood

Coil – ‘The Dreamer Is Still Asleep’

Coil’s Musick To Play In The Dark is arguably their most transcendental record, with sonambulant delicacy in the production giving a meditative, prayerlike atmosphere. Most of all though this is carried through dreamlike LP closer ‘The Dreamer Is Still Asleep’. Four seconds shy of ten minutes of whooshing sonics and eery piano, it manages to be at once sparkling and murkily languid, Machen meets Baudelaire in the sunlit ripples of an English chalk stream that leads to the deathly gurlges of a weir. Most of all though it’s Jhon Balance’s sung vocals that give the song such power. It’s one of my most listened to songs of recent years, and each time seems to have a different resonance with my mood. There’s something about his poetry here (especially likes like "In ten years’ time / Who’ll care? Who’ll even remember?") and the way it breathes its way through headphones on a dark night with an altered mind that can feel like a taunt, an instruction, a warning.

Luke Turner

Current 93 – ‘Twilight Twilight Nihil Nihil’

Much is made of the supposed disturbing nature of the music of David Tibet and Current 93, no doubt due to the esoteric and sometimes bizarre lyrical preoccupations of the project (the apocalypse, menstrual blood, cats etc.). Yet when you get down to the actual music contained on their most celebrated albums – namely the trilogy of Thunder Perfect Mind, Of Ruine and Some Blazing Starre and All The Pretty Little Horses – one sees that much of it is tender and gently psychedelic: a ‘90s take on acid folk. Not so with this track from the latter album.

Producer Stephen Stapleton goes all out for impact on this track, opening with a bowel-rattling bowed drone that recalls the work of his sometime collaborator David Jackman of Organum, and laying the discordant squall of his sinfonie (a kind of proto-hurdy gurdy) on thick. And that’s saying nothing of the spoken word passages that are laced throughout, a nightmarish exposition of guilt, spiritual dread and, of course, nihilism. This is delivered by Coil’s John Balance and antiquarian bookseller Timothy d’Arch Smith, whose haughty, upper-class register is the perfect vehicle for the words: the anguished ravings of a spiritual seeker who has found nothing at the end of their journey.

Danny Riley

Diamanda Galas – ‘This Is The Law Of The Plague’

First lets get things straight: it’s not Diamanda Galas’ astonishing voice that makes this music disturbing. It is not, as her detractors would have it, a witchy, horrorful voice – instead, I’ve found it to be a liberating, euphoric experience to hear Galas sing live. It’s this transportive power of an encounter with a voice that to ears worn down by the anodyne and conventional does not seem to be of this earth that makes it such a vehicle for radical dissections of the horrendous capabilities of human beings.

So this track, which begins with monastic chanting and Galas reciting/appropriating the heinous, shaming commands of Leviticus, is her violent excoriation of the hatred, homophobia and fear with which society met the AIDS crisis in the 1980s. As the piece passes through spoken word, snide, tickling electronics, Galas’ lungs and throat and tongue and mouth creates a sound that rises in a scream of both rage on behalf of, and tribute to, those who were lost, and whose own voices were never heard.

Luke Turner

Earl Sweatshirt – ‘Grief’

It sounds like a finished mind. In its sludgily limbed defeat; its inability to take the bedcovers from over its head; to look at anything at all. Eyes gloopy with sleep, staring at no one in a defiance too exhausted to even be on nodding terms with anger.

Mat Colegate

Eminem – The Marshall Mathers LP

“You’re rapping about homosexuals and vicodin: I can’t sell this shit.” Riding on the wave of controversial breakthrough Slim Shady LP, Eminem’s second major label album found him dealing with the pressures of newfound fame – though it’s hard to say how restricting the industry was actually being, given there are chainsaws, misogynistic death threats and Oedipal images of raping his own mother within the first five minutes. For eight-year-old me and my friends, these songs were comical caricatures with brazen swearing: cartoony tunes with silly lines about celebrities we liked. Whether it was literal or goading (“I say that shit just clownin’”), the reality of the album’s content is undoubtedly bleak and perverse – the shrieking, abusive relationship of ‘Kim’ is especially caustic – and I find it surreal now thinking of how little we understood when we were soaking up his insidious homophobia and singing along to the masterpiece of rap-storytelling ‘Stan’. For all it is chilling, the Marshall Mathers LP is still one of the most fascinating hip hop albums of its time.

Tara Joshi

Gnaw Their Tongues – Teeth That Leer Like Open Graves

This album was probably where Mories de Jong’s particular take on all things decaying and unsettling in his Gnaw Their Tongues guise really broke through to a wider audience than those sombrely clad folk for whom such unwholesome sounds have long been grist to the meatgrinder. The title is unsettling on its own, while the cover and inner-sleeve illustrations of BDSM and butchery are collaged with animal heads replacing those of the active participants, adding to the grim mood set up for the listener’s disturbed delectation.

Merging black metal’s brutal intensity with blisteringly epic Grand Guignol orchestrations from the howling void are bleak enough, but it’s the relentless feeling of misanthropic disgust for humanity at its worst that makes this record stand out among a catalogue of heavyweight misery that stares unflinchingly into the abyss. As with the notoriously macabre Nekromantik films of Jörg Buttgereit, it’s never entirely certain if Mories’s source material is real or constructed – but this album’s bleakest moment is the murder confession on ‘Teeth That Leer Like Open Graves’, where there’s no doubt that it’s all too real, made dreadful and still darker by de Jong’s equally distressing brand of lurching doom and shudderingly visceral electronic noisemongering.

Richard Fontenoy

György Ligeti – Requiem

Composer György Ligeti is one of the few artists to even come close to getting a glimpse of what a possible image of the absolute could be. Having in his youth experienced the horrors of the Nazi death camps and the brutal totalitarianism of Soviet-backed Hungary, he was ready to push the boundaries of what we call music beyond any accepted boundaries, systems, or ideologies to try and find a musical riposte to the horrors of the 20th century. His most profound statement was with Requiem.

Most people know of Requiem from its inclusion in Stanley Kubrick’s film 2001 during scenes such as the discovery of the ominous Monoliths, interstellar gateways whose blackness hints at the infinitesimal vastness of the cosmos. And with good reason; Requiem is disturbing music writ cosmic. The whole piece from beginning to end is utterly inhuman. Starting off with notes and drones so low they’re almost at the threshold of human hearing, before the voices of the two choirs build in intensity.

There are no notes, tonal melodies or prevalent structure. Using the idea of "micro-polyphony", Ligeti piles up the voices and sounds in such a way that music comes at you like a physical mass of abysmal terror hinting at a force that is fully immanent, but never taking on a defined form or presence that we can conceptualise. It is almost the absolute life force of interstellar nothingness coming at you all at once but because we are finite creatures who can’t physically comprehend or experience the universe in absolute terms, you can’t latch onto anything. Play this alone in the dark at night and tell me you won’t feel a hard shudder go up your spine.

Bob Cluness

Jandek – Ready For The House

There’s something uniquely chilling about Jandek’s music (and this eerie debut album in particular) that I’ve never been able to put my finger on. His wavering, hauntingly calm voice and discordant guitar tunings have a deeply unsettling vibe in and of themselves, but there’s more to it than that – much like the album’s curiously sinister cover, Ready For The House’s more mundane qualities and bare-bones aesthetic only barely mask the palpable, frightening sense of decay and malaise that lies beneath. When artists in more bombastic, sonically heavy fields (say, doom metal, industrial, or certain strains of noisy, moody hip-hop) focus on themes like depression and alienation, they can often make these emotions feel like a tangible, physical force through the sheer weight of the music itself.

There’s something very cathartic and comforting about that, as it helps you view your depression as something outside of yourself, as some oppressive external force that can be fought against and perhaps, with the right amount of will power, conquered. Jandek affords the listener no such luxuries; to listen to these bleak, atonal dirges is to stare deep into the cold, dark void within yourself and watch in silent horror as it gradually devours you. There are no peaks and troughs here, no reprise, no hopeful sentiment, no romantic spin on isolation and certainly no inclination that any of your emotions are significant enough to dwell on in the first place; instead, there is only this hollow, uncaring ache that looms over you with terrifying, dogged persistence. Not the best LP to break the ice with at parties, it has to be said.

Kez Whelan

John Zorn – Kristallnacht

Representing the opening chapter of the worst event in human history, John Zorn’s Kristallnacht is an almost absurdly overwhelming musical document of the antisemitic massacre and looting of November 9, carried out across Germany by the Nazi’s SA paramilitary. Minus any Hollywood sheen and minus any sympathetic central characters to tell the story, Zorn deploys multiple techniques and genres over the record, naturally including klezmer melodies and instrumentation, but also weaving in free-jazz fire, concrete collage, and the harshest of possible noise.

Opener ‘Shtetl (Ghetto Life)’ plays passages of angry Hitler speeches over anxious (and beautifully executed) klezmer to represent the quiet before the storm, only to be followed by one of the harshest tracks in existence. ‘Never Again’ spends 11-minutes showering your ears with piercing tones (the original liner notes warned of side-effects including nausea) and endless layers of smashed glass sounds, representing the countless smashes shop windows and destroyed synagogues, and above all the anger, violence, and hatred of evil. The following musical chapters dwell on the event with a mixture or mournful chamber music sadness and naive hope. The knowledge not only that this is all true, but of what happened next, makes Kristallnacht truly disturbing.

As Zorn himself put it: “Every Jew has to come to grips with the holocaust in some kind of way and that was my statement – that’s how I did it. I do not need to do it again.”

Tristan Bath

Kate Bush – ‘The Infant Kiss’

Kate Bush has never been an artist to steer away from the provocative – just listen to The Dreaming, one of the most complex and brilliant albums of the early eighties, and you will understand that she has never played by the rules.

Without the background knowledge for ‘The Infant Kiss’, it can make for a very very uncomfortable listen. On face value, it seems that Bush is writing about being sexually attracted to a young boy. However in 1980 when it was released, the subject of the song was somewhat swept under the carpet. Bush also tended to tell stories from another person’s perspective and inspired by literary greats.

The song is actually based on the 1961 gothic horror film, The Innocents, which in turn was inspired by Henry James’ Turn of The Screw. A young governess looks after two children, one of which is haunted by the ghost of her ex lover – hence the blur between what is deemed appropriate behaviour and the desire she is feeling.

Despite the explanation for the song, one cannot help but feel a sickening chill when listening to the lyrics – but that is perhaps what Bush intended

Lisa Jenkins

Khanate – Clean Hands Go Foul

With a crunch of distorted bass and a mind-shredding shriek, the air is sucked out of the room: this is the effect of Khanate, a doom metal supergroup who could have reinvented metal completely but for whom sadly Clean Hands Go Foul would be the last official release. From that opening blast of ice-cold horror delivered by bassist James Plotkin and supreme vocalist Alan Dubin on ‘Wings from Spine’ to the closing thirty-two minutes of ‘Every God Damn Thing’, Clean Hands Go Foul takes the already bleak nature of the quartet’s two previous albums, Khanate and Things Viral and dissects it to the barest of bones, ratcheting up the unease factor upmteen notches in the process.

Despite sharing the stage and studio with metal luminaries Plotkin (OLD, also a noted producer) and guitarist Stephen O’Malley of SUNN O))), Alan Dubin was the dominant force in Khanate. His vocals are extreme even by metal standards, as he forgoes the cartoonish growl of your average black metal singer in favour of a clear, unhinged howl that sounds like he’s tearing his vocal chords out as he sings. “It’s a sad life/when angels/break/so easily” he screams on ‘Wings from Spine’, his delivery faltering and unpredictable. His is the voice of a man at the edge of his wits, terrified and alone as he contemplates the void of reality. Dubin is aided in his exhausting endeavours by his bandmates, who slowly, unhurriedly carve out wide spaces for him to fill with his blackened poetry. The four pieces on Clean Hands Go Foul are spacious, punctuated by near-silences. Drummer Tim Wyskida is particularly expert in this regard, his unfussy but supple and heavy-where-necessary crashes and fills never overwhelming the space for Dubin.

If listeners more used to pop or mainstream rock will find much to unnerve them when assaulted by Khanate’s unflinchingly austere and lyrically despondent music, Clean Hands Go Foul is also a challenge for metal fans. There’s a lot here that owes a debt to jazz as much it does to metal, in Wyskida’s shifting drum patterns and O’Malley’s brittle guitar explorations, with only Plotkin maintaining anything like a regular nod to bass playing as it’s understood. As the apocalyptic ‘Every God Damn Thing’ emerges slowly, almost ambiently, from the speakers to mutate into a sinister musique concrète outing with Dubin a demonic, susurrating guide, it’s clear this is unlike anything else in metal. Like the gorgeous artwork that adorns it, Clean Hands Go Foul is what you get when you peel the veneer off even doom’s surface to reveal the insane and diseased insides lurking within.

Joseph Burnett

Leonard Cohen – ‘The Future’

Along with ‘First We Take Manhattan’, ‘The Future’ is one of the most illustrative and potent of Leonard Cohen’s brilliant mid-period albums when he managed to combine superficially cheery production values with prescient lyrics of humanity out of sorts with itself – or as he so brilliantly put it, "the blizzard of the world has crossed the threshold / and overturned the order of the soul". All you really need to do to point out why this is one of the most chillingly disturbing songs of all time is to read the lyrics in one browser tab and the day’s news in another. Leonard Cohen saw what was coming. Leonard Cohen was right.

Luke Turner

The Magnetic Fields – ‘I Thought You Were My Boyfriend’

"Your vulnerability is really freaking me out right now" – the best line in The Departed and a reasonable reaction to a lot of Stephin Merritt’s songs. They’re funny too, but then humour is defence, and they’re beautiful songs, which is how they get right into your brain and heart. Disturbing because you relate to the pain, reassuring because you think, ‘Ah, not just me then’.

Anna Wood

Manic Street Preachers – ‘This Is Yesterday’

The darkness of the lyrical themes on The Manic Street Preachers’ The Holy Bible are much-discussed. Richey Edwards, their songwriter along with Nicky Wire, was embroiled in mental collapse, suffering from anorexia and self harm, and would disappear without a trace not long after the record’s release. The album covers these themes, as well as the holocaust, addiction and genital mutilation, and the music is jagged and brutalist to match.

However, for me the most disturbing, affecting piece of music on the record is ‘This Is Yesterday’, which is Wire-dominated lyrically comparably soft. Elsewhere on the record there’s rage, fire and battle to the darkness, but ‘This Is Yesterday’ sounds more like heart-breaking resignation. "I repent, I’m sorry, everything is falling apart," sings James Dean Bradfield, the lyrics stripped of their brilliant poetry to leave nothing but utter, all-encompassing despair.

Patrick Clarke

M.B. (Maurizio Bianchi) – Symphony For A Genocide

An incalculably influential album on the power electronics/harsh noise scene, with tracks entitled ‘Treblinka’, ‘Auschwitz’ and ‘Maidenek’ would probably have you expecting the work of some balaclava wearing atrocity fetishist. But there’s no sheet metal scrapings or impotent rage-letting here. Symphony For A Genocide is insistent, wheedling music, reeling round and round in circles like a horrid toy soldier on a battered trike. Senselessly repetitive, more than a little pathetic, and possessed of mesmeric and unnerving power, Maurizio Bianchi here has made a hideous testament to man’s unerring stupidity and arrogance.

Mat Colegate

Nina Simone – ‘Strange Fruit’

One of the most important songs in the jazz canon and also one of the most impactful songs in American history, ‘Strange Fruit’ carries emotional scars and leaves just as many in its wake. The song’s extended metaphor compares the hanging bodies of tragically lynched African-Americans to strange fruit, their blood fresh on the leaves but also soaked deep down to the roots of the American south. And while the song was written by poet Abel Meeropol and made famous by Billie Holiday, the inimitable smoky growls and pained reaches of Nina Simone truly radiate the disturbing power of the song grown full life. After all, Eunice Kathleen Waymon took on the stage name Nina Simone so she could adopt a new persona and disguise herself from her preacher father and family members who denigrated her music down to the “devil”.

She wound up doing god’s work by addressing inequality and inhumanity here. The imagery is stark, bleak (“Here is fruit for the crows to pluck”), and Simone’s equally unflinching recitation reiterated the endless struggle of black Americans decades after the abolition of slavery and yet in the throes of the civil rights movement. Her voice is a meditation on the way one can capture time, her irresistible rhythmic technique allowing her to sink behind the melody and uproot it from below. For Holiday and Simone, the song was met with protest, outrage, and riot, showing even further its necessity as protest song. The sound reflects the roots of her work and how she’s able to grow within such devastating occurrences. ‘Strange Fruit’ remains disturbing in its harsh reality and eerie orchestration – and tragically for the fact that its ability to put listeners in the shoes of a heartbroken yet defiant black American is just as needed today as the 1960s or 1930s.

Lior Phillips

Nurse With Wound – Homotopy To Marie

Recorded between 6pm and midnight in a Shepherd’s Bush basement studio every Friday for an entire year, Homotopy To Marie is an overwrought work of surreal horror, spliced and edited with malicious intent by NWW’s lead man Steven Stapleton. The sheer amount of empty space in the music is imbued with a constant sense of threat, perhaps never more so than in the gong hits, mumbled voices, and gently scraped strings of the lengthy title track. Unnecessarily piercing tones are also added throughout to maintain discomfort (and I suppose to keep any accidentally pleasant ASMR or Zen-like side-effects of the mood at bay).

Almost all of side two comprises ‘The Schmürz (Unsullied by Suckling)’, the least brooding and most varied track, summoning a mood that’s less paranoid and more sonically violent. A wider variety of rough noises, with snatches of all kinds of instrument, plus a multitude of speaking and screaming voices (including that of JG Thirlwell) get brought into the long and uncomfortable collage, periodically making the listener jump slasher-movie style. Horror mood aside, it’s also a hell of a masterpiece of analogue editing by Stapleton, seemingly capturing the brink of madness right down onto tape.

Tristan Bath

Public Image Limited – ‘Death Disco’

Despite its awful inevitability, the death of one’s mother is undoubtedly the most profound event that any of us will experience. And probably more so when it’s the result of a long and tortuous illness that slowly, methodically and painfully eats away from the inside the person that conceived, carried and nurtured you to leave little more than a sunken and crumpled shell.

That profundity increases to almost unbearable levels thanks to an impotence that didn’t allow you to stop the disease or the feeling of shame that follows that sigh of relief when the suffering ends with her terminal breath. And that feeling of cold fear and cosmic loneliness as the realization hits that that one source of unquestioning shelter is no longer here to protect and sooth washes over you with the unyielding force of freezing cold waves.

‘Death Disco’ is precisely all that with even more confusing emotions and an endless howl of rage to a universe that refuses to listen to you thrown in for good measure. It disturbs because it reminds not just of that event but also your own shortcomings as you’re left to measure up to what you think her standards might have been. ‘Death Disco’ is the naked truth and that’s what’s so disturbing about it.

Julian Marszalek

The Residents – Duck Stab

The closest I’ve ever come to having a nervous breakdown primarily because of the intense unpleasantness of a piece of music, was while driving round Bristol in a van, helplessly lost while listening to Duck Stab at full volume. If anxiety has a natural soundtrack, this is it. I know The Residents are important because of art and music and eyeballs and blah, blah, blah but if I had the technological ability I would round up all copies of this record, including the master tapes, nail them to a missile and fire it straight into the heard of the sun. Especially the song ‘Constantinople’. That can properly fuck right off.

John Doran

Rhoda Dakar With The Special AKA – ‘The Boiler’

At 14 years old I received my first record player. While charity-shopping for something to play on it, I came across a compilation album of singles from 2 Tone – at the time one of my favourite record labels. At the end of Side B, after the expected hits from The Specials, Madness and The Beat, as well as some jaunty trombone instrumentals from Rico, came ‘The Boiler’, in which Rhoda Dakar narrates a story of being raped.

Educated at the time in the hyper-masculine environment of an all-boys school and sheltered from many of life’s darkest realities, The Boiler was the first time this taboo had been breached. Rape and sexual assault was simply not discussed in this environment – it was an abstract concept, and occasionally the punchline to the vulgar jokes of the most crass classmates. Rhoda Dakar’s story, so uncompromising and matter-of-fact in its delivery as it builds towards a final, chilling end, left me dismayed and overwhelmed with stark, bleak reality. It was one of my first glimpses at the grim world beyond my privileged ignorance.

Patrick Clarke

Richard Dawson – ‘Poor Old Horse’

Witnessing the Newcastle born musician Richard Dawson tackle his a capella song ‘Poor Old Horse’ live is always something of a joy to experience. Not only does he seem to physically transform during the performance (from jocular saloon bar cove to worrying ursine shapeshifter) but such is the power of the delivery the audience themselves seem to shift in nature somehow. I can’t think of any other situation where so many people would join in so enthusiastically, singing along full pelt to a song about animal cruelty let alone regarding drunks trying brutally and haphazardly to kill a horse. Weirder still is how hilarious most people (myself most definitely included) find the lyrics and delivery.

There is something slapstick about the sheer cack-handedness of Bill, Ned and the foreman admittedly but it doesn’t account for the scenes of near giddy hysteria I’ve seen during some renditions. But the laughter often masks the point at which the real disquietude starts seeping out from the lyrics. (“Now each he goes his separate path/ For a cup full of ale or a nice hot bath/ A kiss on the lips of a wife newly wed/ Or a look at the baby sleeping in bed.”) Is the song even about what it seems? Dawson often plays the role of a seer horrified at what he’s envisaged – in this case the senseless violence of men, and how this in turn affects their families and is passed down like bad genetic code from each generation to the next.

John Doran

Scott Walker – ‘The Escape’

“It’s quiet… a little too quiet”.

A phrase used so many times as to make it a cliché. But not without reason. When the birds stop chirping, ancestral man knows that danger is present.

‘Prey moves, predator moves’.

When the horror music dies down, that’s when hackles raise highest and knuckles grip tightest to armchairs.

‘Windblown hair in a windowless room’.

‘The Escape’ lurches at a black-leather pace, Scott’s trademark creep-tic imagery oiling in-and-out of sense; strings stalking and ebbing. Inertia juxtaposed with intensity.

‘Look into its eyes’ I’d really rather not…

‘It will look into your eyes’

And then the abyss. A perfectly-timed eternity of near-silence save for the highest, most wavering violin note. And then… Well, I’ll let you find out for yourself. Sublime, ridiculous and enough of a jump-scare to almost throw me off my bike into oncoming traffic that one time. ‘The man behind the dumpster’ of musical moments.

Charlie Frame

Shirley Collins – Lodestar

Even in her 60s and 70s heyday, with her English rose image and Arcadian depictions of pre-industrial Britain, Shirley Collins was wont to explore the darker side of human existence as revealed by folk song. Yet this exploration was never so stated as in the opening salvo of Lodestar, her comeback album after 38 years of relative silence. You’ve got ‘Awake, Awake’, a fire-and-brimstone exhortation promising rotting bones and melting flesh to sinners,’“The Banks of Green Willow’, in which a young woman and her baby are drowned, and then – perhaps most disturbing of all – the gory murder ballad ‘Cruel Lincoln’.

It’s the major key of the song, along with Collins’ unadorned, emotionally muted delivery that gives lines such as “There was blood in the kitchen, there was blood in the hall” such a vividly disquieting quality. Later, we have “Death and the Lady”, a dramatic rendering of humanity’s relationship with mortality, proving that existentialism wasn’t invented by Left Bank intellectuals, but was part of the daily lives of the ordinary people who sung such songs before the advent of modernity. Folksong is often admired for the perennialism of its themes, and songs such as those sung by Collins on Lodestar are a constant reminder that the darkness will always be with us.

Danny Riley

SoulFly – ‘Tree Of Pain’

I’m not the only father who would give his life if it meant that his offspring would be safe. I’m sure I’m also not the only father whose love for his kids surpasses explanation, because I’m a dad first and everything else second. I’m saying all this parenty stuff because it explains the impact that Soulfly’s 2002 song ‘Tree Of Pain’ always has on me.

Soulfly are a metal band from Arizona, led by my friend Max Cavalera, previously of Sepultura. You may or may not like either band, it really doesn’t matter. Max wrote this song – and others before it – about his stepson Dana Wells, who died in a car crash in 1996. The police concluded that it was an accident; Dana’s family maintain that it was murder. There’s been little closure over the years, hence the sickening anguish in this song. Musically, it’s genius: after a sweet ballad intro, ‘Tree Of Pain’ suddenly becomes a very fast hardcore tune with a massive breakdown in the middle. Dana’s younger brother Richie does a guest vocal and, even though he was just a kid at the time of recording, forces so much enraged hurt into the song that it brings tears to my eyes every time I hear it.

Joel McIver

Sounds & Silence – ‘The Lyke Wake Dirge’

A lyke is a corpse. A wake is a vigil to hold for a corpse as the soul begins its journey. A dirge is a lament for the corpse. So far, so eerie this passage of words, so heavy with darkness, with the passage of time.

This ancient song was first woken in the 1960s by folk band The Young Tradition, before being popularised by Pentangle on their top ten folk-rock album, Basket Of Light, its lyrics taken from a 17th century manuscript by the English folklorist John Aubrey. It documents in medieval dialect from the North of England the obstacles one could face after death. A “whinny-moor” of gorse that could prick your shoeless feet to the bone. A “brig [bridge] o’dread” carrying you over the rivers of hell. “Purgatory fire” that could “burn thee to the bare bane [bone]”. Now imagine a slow, low drone. Out of nowhere, the pouring of water. The dopplering shivers of a gong. A two-note, slow, repetitive minor-key figure on the lower notes of a piano. Then the sound of a young girl trembling and shivering, then whispering: “This ae night/this ae night/Every night and alle/Fire and fleet and candle-lighte then Christ receive my saule”. An older, croakier voice joins her, a faceless phantom from the deep, and the volume gets louder and louder, before they all die away.

This version was made by a school class, recorded by John Paynter (a working-class progressive composer who became a professor at York University) and Peter Aston (who Benjamin Britten chose to lead the music department at the University of East Anglia), for their 1970 Sounds of Silence LP, liberated and featured on Jonny Trunk’s 2013 compilation album, Classroom Projects. Every time I listen to it, or even think of it, I am chilled to the bone.

Jude Rogers

Stalaggh – Pure Misanthropa

All the vocals on this album are allegedly the work of mental patients recorded by a member of Stalaggh who works in a psychiatric hospital. You find yourself listening intently for clues – is this genuinely the work of the mentally disturbed or just a particularly animated bunch of performance artists? Every so often a scream cuts through the sludge like a chainsaw through wool and you are totally convinced that it’s not the work of a rational mind. You find yourself really hoping that the story isn’t true – why shouldn’t it be? It’s not beyond the realms of belief, is it? – and horrified that part of you enjoying the music hopes that it is.

Mat Colegate

Suicide – ‘Frankie Teardrop’

Announcing their self-titled arrival in a spurt of spilled blood and a name calculated to prick even at the sleazy, nihilistic heart of New York’s punk scene, Martin Rev and Alan Vega extracted themselves from guitar-bass-drum template and established the angry singer and laconic keyboardist paradigm on the way. Sneering and snarling, Vega took Elvis’s swagger and made it mean something new; shades-clad Rev swayed behind keys and drum machines grinding out the minimal garage groove, and together they provoked riots and ruckus.

‘Frankie Teardrop’ opened side B of Suicide’s self-titled début LP, Rev laying the still-uncanny groundwork for Vega’s heartfelt rendering of a tale of the ill-fated titular anti-hero ‘who just can’t make it’ in a menacing haze of pulsating electrical hiss and a moody drone melody ideal for listening to when the lights are low and entirely strung out.

Getting evicted, starving, his fall into heroin laid out like an inevitable consequence of poverty and desperation and with infanticide on his mind, Suicide pull no sucker-punches here. Vega’s visceral shrieks pulverise any shred of hope or semblance of escape for Frankie in gathering clouds of crumbling, shattering echoes and mordantly fragile organ stabs that speak volumes of despair and abject misery like few had done before – or since.

Richard Fontenoy

Third Ear Band – Music From Macbeth

If you’ve not listened to the Third Ear Band, everything you’ve heard about them is wrong. As with some of their more bucolic contemporaries, words like “hypnotic”, “drone” and “medieval” are thrown around a lot. So, when I picked up a copy of their soundtrack to Roman Polanski’s Macbeth in a Totnes Oxfam (where else?) I was, perhaps naively, expecting tranced-out acoustic jams in the vein of Forest, Incredible String Band et al.

How wrong I was. From the unsettling “Overture”, with its queasy clarinet and scraping viola vying for ground in an atonal improvisation, right down to the wheezing reeds of album closer ‘Wicca Way’, it’s a bleak and disquieting work that offers little reward to even the most obstinate listeners. In short, it’s the kind of music you’d imagine a tribe of goblins would play as they gleefully pull your intestines out. Hippies beware.

Danny Riley

Today Is The Day – Sadness Will Prevail

If it’s disturbing, violent and uncomfortable music you’re after, you could take your pick of Today Is The Day’s back catalogue, but for me, this double-disc opus still stands as their most uncompromising and troubling record. Following an album as immediate and visceral as 1999’s In The Eyes Of God with a sprawling two-and-a-half-hour-long exploration into isolation and deep-seated self-loathing was a polarising move, but the diverse Sadness Will Prevail uses the extra space to its advantage, painting with an extremely broad emotional palette that makes it bleaker moments seem all the more disturbing by contrast.

Akin to the frenzied, disorganised mind of a schizophrenic, the first disc alternates between some of their heaviest, most aggressive material and moments of stark, vulnerable introversion (check out the way ‘Crooked’s rabid bark is followed by the scattered, damaged psychedelia of ‘Butterflies’, or how the Swans-esque clatter of ‘The Descent’ segues uneasily into the dramatic piano-led ballad ‘Death Requiem’).

On any ordinary record, the tortured honesty of the title track would have made a fitting finale; here, it works as the album’s heartbreaking centre-piece, closing disc one and signalling the descent into even more depraved and hopeless terrain on disc two, like the abrasive, disfigured noise of ‘Spaceship’, desperate ode to self-medicating ‘Breadwinner’ or the 23-minute mental-breakdown-in-musical-form that is ‘Never Answer The Phone’.

You could argue that Sadness Will Prevail is overlong, self-indulgent and pretentious, and to some extent, you’d be right – but it’s also one of the most scarily compelling depictions of deteriorating mental health that extreme metal has ever produced, and for that reason alone, it’s worth investing the time in. Just don’t expect to feel the same once you come out the other side…

Kez Whelan

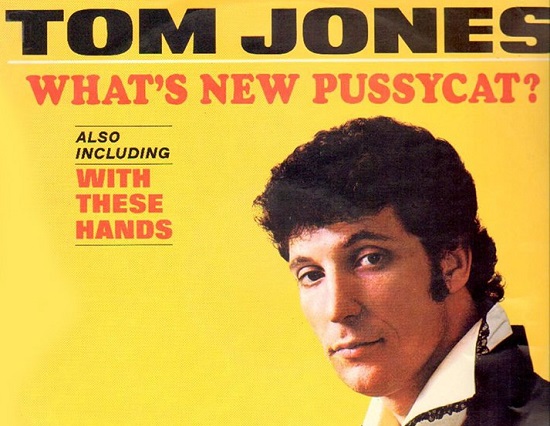

Tom Jones – ‘What’s New Pussycat?’

I first heard ‘What’s New Pussycat?’ a couple months ago, when some sick bastard played it two or three times in a row on the jukebox at the local.* I sat there in shock, mouth agape, horrified at the thought that this might never end.

When I listened to the way that Bacharach’s inane, lolloping, singsong melodies colored Hal David’s infantilizing, casually sexist lyrics, it became skin-crawlingly creepy. I was struck by the image of a foul, corpulent banker, pathetically besotted with a much younger mistress, chasing the poor girl around an expensively furnished apartment that he pays for.

And the real horror is that all of this is supposed to be ‘hip’: Here is base lechery dressed up with debonair flair. This is the song of the “man in the grey flannel suit” preparing for a night on the town in Swinging London, or of the London swinger who is exactly the same kind of drooling scumbag as the suit he disdains. When I read that this was first recorded for a movie written by Woody Allen, it all made sense.

*In what my sister tells me was homage to someone named John Mulaney.

Pavel Godfrey

V/VM – ‘The Lady In Red (Is Dancing With Meat)’

I have always hated Chris de Burgh’s original. A real sleazebag of a record. A Daily Mail version of romantic. The sort of record you’d imagine coming top in a UKIP poll. Chris de Burgh looked like he’d been plucked from an eternal Pebble Mill and shoved into a shiny suit, yet still had the allure and charm of out-of-date ready meal. Even in the context of 1986 pop – quite a gruelling year – he manages to make Phil Collins look like Morrissey with his naffness.

I first heard V/VM’s mangling of it years ago, on an album where he’d done the same to a variety of eighties power ballads. The sort of disbelief, and initial amazement, at it all appealed to me. It was the dawn of the era of sharing and discovering a new thing every 30 minutes on the likes of myspace, and finding something not many other people may have heard was a bit cool. I was quite interested in it from a musician point of view. I’d always quite like sitting through something like extreme that would make other people wince. But the novelty was enough. I’d stick this on a CD compilation to freak a friend out, and it was her playing it again a few months later, decompressing from a night out and having a last smoke before bed, where it gave me the fear.

Sitting in her kitchen, as it played, is about the nearest to the horrors I’ve probably ever approached. It started making me feel really ill, queasy and nauseous. I can’t fully describe it. It felt like de Burgh was actually there. Melting like the seaside waxwork he is as he sang his hit. I’d compare to something out of Hellraiser tbh.

Since then, even happening upon the original on the radio, it’s this version that bleeds through instead. It’s what I imagine being cremated in a branch of next feels like. No offence to V/VM whatsoever, they’ve been behind some great stuff, and even this is amazing, in some way, but also genuinely horrible.

Ian Wade

White Noise – An Electric Storm

An Electric Storm, by the Delia Derbyshire and Brian Hodgson project White Noise, has gone down in the history books of electronic music as a revolution. Released in 1968, it is quite genuinely one of the most pioneering records ever recorded.

It’s also one of the most downright terrifying, eerie, proto-Broadcast sing-song vocals about swarms of fleas juxtaposed with manic effect, most notably the the distorted sounds of some kind of twisted orgy. There have been many musical visions of the underworld, but this album’s final climax ‘Black Mass: An Electric Storm In Hell’, is up there with the most utterly petrifying.