The idea of rock & roll being the devil’s music seems quaint now. The ‘Prince of Darkness’ recently passed away as a beloved uncle figure, and Satanic panic is distant in the rear-view mirror. It may be a sign of the cynicism of our age or the duplicity of earlier times but it’s music from before rock & roll that now seems uncanny, too innocent and smooth, and thus indicative of things not being what they seem, perhaps even secretly monstrous. This feeling has been put to fine use by David Lynch, Pina Bausch, The Caretaker and others. One figure that continually reoccurs in this regard is Al Bowlly. A suave 1930s crooner, who sang at the Raffles in Singapore, and was ultimately killed in the Blitz, is now invoked as a phantom to bestow eeriness upon all manner of projects. When Momus wanted to drag his heartbroken wretch to hell in the song ‘Core’ he did so via the Bowlly song, ‘Guilty’. When Kubrick wanted to bring a sense of infernal damnation to the Overlook Hotel in The Shining, he did so with Bowlly’s song ‘Midnight With The Stars And You’. Travel so deeply into schmaltz, magnificent as Bowlly’s version of it is, and things turn very weird, as captured by Hilary Lloyd’s sublime Dennis Potter-inspired contemporary exhibition Very High Frequency at Studio Voltaire, London, until the 11 January next year.

“Potter works best late at night” Gordon Burn noted, “with the radio on or, better still, a selection of old Al Bowlly records playing quietly in the background. More than once, he says, odd phrases picked up from those songs have triggered off ideas used in his writing.” The psychopomp is an ancient idea in art, the ghost who leads the hero through the underworld. Bowlly is not, however, the psychopomp in this relationship but rather it is Potter who guides Bowlly, a shade from an earlier age, through so many of his plays (Moonlight On The Highway, Rain On The Roof etc.) and in doing so through the purgatory of the modern age.

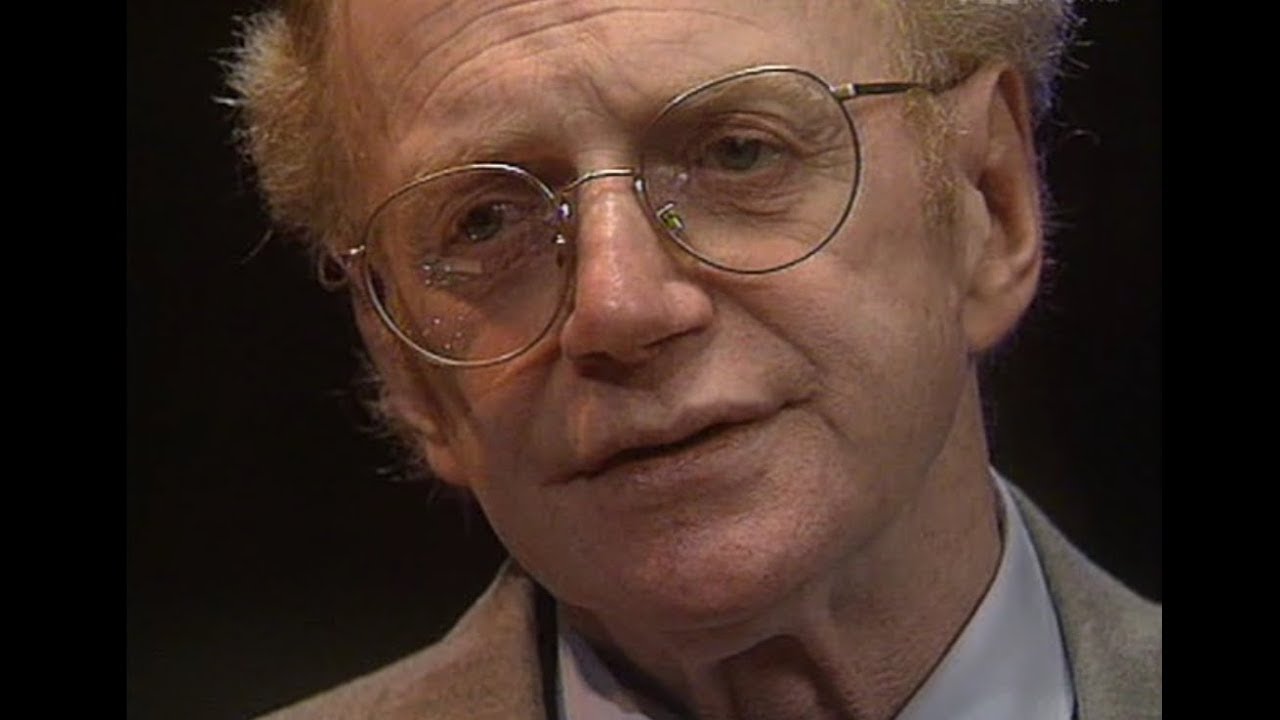

Hailing from the coal mining territory of the Forest of Dean, Dennis Potter faced the classic problem of the working class artist – its necessity and impossibility. To move beyond the land and its trades, regardless of the encouragement of kith and kin, was and remains a form of betrayal. Or so it is often perceived. Potter made it to New College, Oxford (“one of the darkest places in England”), where he was interviewed for BBC documentary Does Class Matter. There’s a tragedy to his observation then that “it’s not the social gulf between the classes that’s interesting, so much as the way the gulf is narrowing” given the chasm it is now, to the detriment of everything. The reality is that the proletarian would-be artist enters a social hierarchy with its own passive aggressive language, mores, sacrileges and gatekeepers, where they will be perceived as, at best, a fleeting novelty and, at worst, a threat.

The resulting condition is one of exile, between worlds; an advantageous perch for a writer but a tricky one for a human being of any sensitivity. This might partially explain the attraction Potter had to uneasy or suspect outsiders in his work – the father of mesmerism Franz Anton Mesmer, Casanova, the poet Edmund Gosse, the painter Graham Sutherland, Christabel Bielenberg, Charles Dodgson aka Lewis Carroll. He was able to speak through them on matters like faith and doubt, innocence and guilt. The surrealistic non-naturalistic quality of Potter’s writing, merging stark psychological realism and staid domesticity with fantasy sequences, noir, music hall, dreams, pastiche, flashbacks, science fiction, sinister supernatural undercurrents, collage, Brechtian alienation effects, was a huge and acknowledged influence on David Lynch and Mark Frost, as evidenced in Twin Peaks. This was a conscious decision, to avoid being corralled into the ‘grim up north’ (or rather ‘grim out west) ‘sell your trauma lifelike and lifeless’ trap that working class writers are forced into. There’s as much anger in this work as summoned by any angry young man (or Shelagh Delaney, Andrea Dunbar and co.) but Potter refused to be boxed in to the establishment’s view of what working class art could or should look like. Potter mocks the idea of a box, playing with it at times, but only to goad those with reductive impositions and expectations into a false sense of security. Those insisting on trauma porn should have been careful what they wished for, given Potter hit hard with both and rarely in an expected way. I used to think of Dennis Potter as a kind of escape artist, exploding the box in innumerable directions, but he’s more interesting than that. He’s already outside, already an outsider, examining the box from without, thinking, ‘Well, isn’t that quaint? I could do something with that’ and then reconfiguring it into shapes and combinations hitherto unheard of and unprepared for.

There is more realness in Potter’s weirdness than in the majority of overwrought series striving for authenticity – all those one-word ‘issues’ melodramas with their muted palettes and actors staring morosely from clifftops or tower blocks. Consider, by contrast, Potter’s Blue Remembered Hills (1979), where adult actors recreated the Forest Of Dean he knew as an infant, albeit with a terrible fiery twist. Subjectivity doesn’t just matter, Potter suggests, it is inescapable, especially when recreating the objective. Memory is an unreliable narrator and it’s best to embrace the artifice/distortion (we are built of such things) and utilise the possibilities therein. Certainty, by contrast, is a lie; a comfort at best and deception at worst, “They be funny things, words.”

One of the dirty secrets of writing is that is no such thing as non-fiction and no such thing as fiction; not in any kind of absolute or pure sense. Both are contained within and vital to the other. A fresh-faced young Potter started with a direct empirical approach, creating Between Two Rivers (1960) a documentary on the Forest Of Dean. It is insightful, loyal and soulful (“the green forest has a deep black heart”) and it was rewarded with ferocious hostility by many, “The bulk of the people in the Forest of Dean loathed a television documentary I wrote about the place, where, quite honestly, I thought they would be sort of proud of me for what I said in it.” It was a devastating response but one that forged, painfully, the wisdom and impish qualities of the writer to come. (And who’s to say the people of the Forest of Dean were not justified in being suspicious of the attentions of the intellectual class?) Potter was forced somewhere more interesting than sincerity: “I am beginning to acknowledge a perverse element of self-dramatisation in all this.” There is no containing whatever mercurial quality Potter possessed but he came close to pointing out the north and south he was navigating by: “I once said you should always look back on your past with tender contempt. Tender is important.”

Experience in politics liberated him from polemic. Desiring “to close the gaps between the governed and the controllers at all levels”, he stood for Labour in the 1964 General Election, but lost to the Tory candidate, lacking the self-confidence to cast a vote for himself. Parliament’s loss was television’s gain, with the experience providing plentiful material for Stand Up, Nigel Barton and Vote, Vote, Vote for Nigel Barton (1965). It led too, indirectly, to works like Traitor (1971), which explore the entanglements that lie beneath dogma and which fuel treachery. Potter mined the period when he was employed as a Russian language clerk in Cold War-era Whitehall for this piece and others like Lipstick On Your Collar (1993), Lay Down Your Arms (1970), Gorky Park (1983), and Blade On The Feather (1980). Politics can be the alibi for ego-driven cruelty, disloyalty and deception, and is where broken hearts contend with dead bodies.

Potter never ventured too far, or at least for too long, from the Forest Of Dean no matter how bizarre the subject matter. Occasionally he would even relocate stories to his native locale or dialect. When he looked the place in the eye, the result was filled with that tender contempt. A Beast With Two Backs (1968) examines the fear of the ‘other’, via a true case where a French circus troupe, with dancing bears, were attacked by a mob after a local girl was ravaged. Similarly, Blue Remembered Hills (1979) is not overburdened with nostalgia or at the very least its nostalgia is carried on a chill wind. Its title comes from A.E. Housman’s ‘A Shropshire Lad’: “Into my heart an air that kills / from yon far country blows”, which bears the seeds of its own negation, loss and palpable menace. “What are those blue remembered hills / What spires, what farms are those? / That is the land of lost content, / I see it shining plain, / The happy highways where I went / And cannot come again.”

The guiding principle of the BBC was “Inform, educate and entertain”, as set out by Lord Reith. While this sounds like public service, it also reveals an old school top-down paternalism and even social engineering. Potter was more of a bottom-up democrat claiming, “Television is the only medium that relay counts for me. It’s the one that all people watch in all sorts of situations. Television is the biggest platform and you should kick and fight and bite your way on to it. It’s true that television is endemically a trivialising medium, but it doesn’t follow that it has to be. Television is the true national theatre.” From his televisual play days onwards, Potter not only embodied what was possible in a largely disregarded medium but pushed way beyond its bounds, crucially because of his faith, correct as it happened, that the audience would accompany him. There was no condescending sense with Potter – all too present today as then – that the public were idiots who needed to be intellectually housetrained, by their enlightened ‘betters’. In challenging this, Potter ran into problems not just with censors but amongst institutional philistinism with The Confidence Course (1965) and Message for Posterity (1967) being lost or recorded over. Television was not treated as a particularly serious medium, something Potter upended not by performing ‘seriousness’ but by bringing out the possibilities few had believed it contained. It was, after all, stranger than assumed – a box of light in the corner of a room that hypnotised people by showing them other people’s lives, a portal that was partly surreal from its inception with that flickering image of the ventriloquist dummy Stooky Bill on John Logie Baird’s first transmission.

The prophetic quality of Potter’s work was amplified by his lack of patrician ‘how the world should be’ television as tonic. Deception is a major recurring theme, as it is in life. Potter could spot bullshit a mile away, hence the early exposure of shyster lifestyle gurus in The Confidence Course (“We can give you the confidence which gets you places!”). The damage wrought by tabloids on the collective consciousness is predicted by the increasingly demoralised and unhinged protagonist of Paper Roses (1971), with Potter being clever and meta enough to have it all watched over by a disdainful critic: “Last night’s TV play, Paper Roses, gave us about as true a picture of popular newspapers as a funfair distorting mirror.” Even when horrors are unleashed, the blob manages to absorb and recycle them while denying all culpability. America’s surpassing of Britain is there in The Bonegrinder (1968). By Visitors (1987), it’s a corporate eclipsing. There’s a western-obsessed proto-incel in Where The Buffalo Roam (1966), a reminder that marginalisation does not equate to sainthood for all. When Potter revels in visual fantasias, bringing John Tenniel’s illustrations to life in Alice (1965) and Dreamchild (1985), it is still anchored in the children’s tale as a shadowy psychological exploration of its creator. In Follow The Yellow Brick Road (1972), the toxicity of consumerism accelerates an actor into mental illness.

God, and his absence, is often present. Joe’s Ark (1974) is a critique of faith told via the dying daughter of a bible-bashing pet shop owner. There is a sense throughout Potter’s body of work of being bereft from God, without even the comfort of atheism but instead subject to just more uncertainty. In Son Of Man (1969), he has Jesus lament to a cross, “You should have stayed a tree, and I should have stayed a carpenter.” St Paul’s Epistles recur several times throughout his work, haunting and mocking him and us, always just out of reach. Even in the most secular of places, the Soviet betrayal dramas, religion is in the air and silences. Potter specialised in a form of visitation play, whereby demons or angels (sometimes indistinguishable) would interrupt suburban lives and sow havoc. They seem all the more remarkable now because they suggest evil exists, something of a heresy in our age, despite being surrounded by ample evidence of it. In Schmoedipus (1974), conventional life is thrown into disarray by the arrival of a seductively demonic figure, from the darkest reaches of Freudian psyche, in the perfect form of a young Tim Curry. This was something of a mirror piece to the earlier Angels Are So Few (1970) but it was a device Potter would use again and again – Shaggy Dog (1968), Track 29 (1987) etc. – allowing him to explore issues such as class, chance, desire, revenge, victimhood and so on. So powerful and disturbing was the visitation of 1976’s Brimstone And Treacle (the title a subversive spin on the benevolent visitation of Mary Poppins) that the BBC banned it.

Dennis Potter may have left religion behind, but it never left him. His dramas with angels and demons were not just studies of our worst and best selves, the two almost impossible to neatly segregate, but a battle forced upon him by chronic illness. His puckishness in his work masked, or was a weapon against, the cruelty of the psoriatic arthropathy that beset him in waves for years, forcing him at times to stop writing or to do so with a pen lashed in his bleeding fist. Like Proust or Bousquet, what else was there to do but write? Television was a portal not primarily towards for Potter, as it is to us viewers, but outwards. He was not afraid to address the societal stigma, and degree of reclusiveness, that came with a disfiguring debilitating illness (this was not a condition that bolsters your C.V.), using this to powerful effect in The Singing Detective. Just as he heard the angelic Psalms of David in the old Bowlly records that served as his writing soundtrack, he struggled with a lingering sense of being inflicted with a Biblical Job-esque curse, which he bore with extraordinary prolific fortitude. It led him to a profound form of sympathy, tinged with the caustic, “I recall writing (and the words now make me shudder) that the only meaningful sacrament left to human beings was for them to gather in the streets in order to be sick together, splashing vomit on the paving stones as the final and most eloquent plea to an apparently deaf, dumb and blind God.”

Pennies From Heaven (1978), The Singing Detective (1986), Lipstick On Your Collar (1993) and others are, rightly, celebrated as his masterpieces, though unfairly overshadowing an entire career full of genius plays and moments, however fragmentary. Named after a Bowlly track, Double Dare (1976) begins with the Potter trope of the screenwriter with writer’s block fantasising an illicit life, leading the viewer to wonder where it ends and its creator begins. The playwright enjoyed playing these meta games and they are an integral part of a puzzle that ends in an exquisite, disturbing and genuinely astonishing twist. In many cases, you can visualise Potter writing in your mind’s eye, constricted by space and illness, and the resultant plays, films, novels and episodes being a tour of the inside of his head and the mechanics of storytelling itself, with conceits like characters turning against their authors or plays within plays. It’s easy to overstate Potter as an imprisoned recluse – he was after all a devoted family man – but there is something noble and incredibly imaginative in the ways he defied containment, “To see a world in a grain of sand” as another working class hero put it.

Naturally, this approach stirred up ire, as did his taste, or rather life’s taste, for the explicit. Blackeyes (1989) faced a pincer attack from his traditional conservative adversaries and liberals who took umbrage with its supposed misogyny, marking the beginnings of a dumbing down of culture and absurd literalist misreadings and misrepresentations that blights us still. “It alienated every fucking person who ever saw it!” Potter later remarked. The author certainly knew he was operating in dangerous territory, “Recollections of abuse – my god – they’re hard to deal with – even though I try… There are times when the pen in your hand becomes… becomes – yes – a knife in someone else’s.” Yet he could scarcely have imagined that society would become so disapproving towards the examination of issues like predation in fiction that it would conspire to hide their real-life existence. Etiquette became a tool of erasure that Potter’s most infernal visitors could only have dreamt of with relish.

“The art of living well and dying well are one” Epicurus claimed. By the time of Cold Lazarus (1996), Potter knew he was dying of pancreatic cancer. He named his tumour after Rupert Murdoch and noted, in a compelling final interview with Melvyn Bragg, with typical mischievous sparkle, that the diagnosis was a Valentine’s Day gift (“a little kiss from somebody”). There is so much within the dystopian production of Cold Lazarus (and its predecessor Karaoke) that it feels like he, and we, were robbed of so much unwritten work. Yet the subject of Cold Lazarus was very different, even antithetical, to what might be expected from someone whose time was coming to so premature an end. We need only look at the political/economic gerontocracy or tech bros trying to live forever to begin to learn the wisdom of Potter’s final prophecy. You pay the debt of life off by dying. Anything else is cheating the Gods and its rewards would be its punishment. To live forever would be the curse of all curses. Instead, there was in Potter’s last days, dignity, wit, generosity and a quiet heroism, not a raging against dying of the light but an examination of it, as it fades down to a white dot, the screen-burned ghost image of what was once alive, and the sound of Al Bowlly from another room or another place entirely.