Richard Wagner’s utterly preposterous The Ring Of The Nibelung is a cycle of four operas ranging in length from two-and-a-half hours (opener Das Rheingold) to five (Götterdämmerung, its final part) and totalling 15. It features characters from Norse mythology – gods, water-nymphs, giants and dwarfs – and it’s intended to be staged on consecutive nights, which has always proved to be a test of endurance for listeners. Tchaikovsky scored tickets for the 1867 premiere at the opera house Wagner built especially for it in Bayreuth, Bavaria, and later wrote: “After the last notes of Götterdämmerung, I felt as though I had been let out of prison.” Parts of it bored him and he thought some of the music was “too complicated and artificial”, but he was nonetheless impressed, noting that it contained “many passages of extraordinary beauty” and was “an epoch-making work of art”. That combination of views is pretty much how all but the most hardcore Wagnerians think of The Ring today.

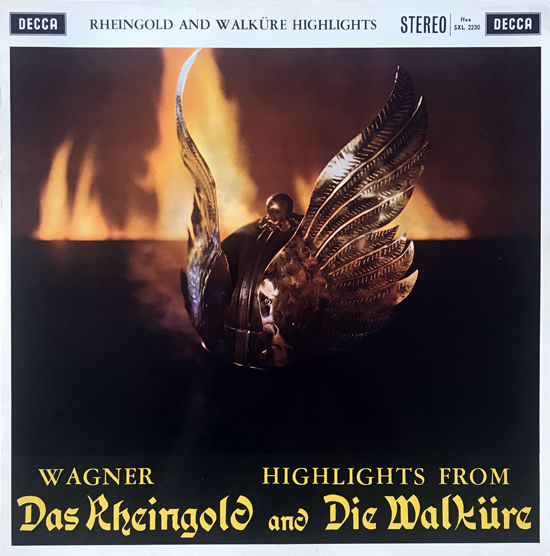

If the prospect of listening to even one part of the cycle feels intimidating, imagine what it takes to record the work in full. No one had attempted to do so before British label Decca began the arduous process in Vienna in 1958. There had been live recordings of all 15 hours and a couple of radio broadcasts, but no meticulously crafted, studio version that respected every eccentricity in the 2,000-page score and made trailblazing use of the then-new technology of stereophonic sound to boot. By the time the producer of the project, John Culshaw, had captured the final notes on tape it was 1965. He hadn’t been working on The Ring exclusively, but it was still the most ambitious and risky experiment in the history of the record business at the time. It birthed 38 sides of vinyl split into four boxsets (one for each of the operas, released sporadically across the seven years), as well as single-vinyl highlights albums, like the one at the top of this article, of excerpts from Das Rheingold and Die Walküre.

Culshaw must have wondered what was going on in the world when he finally came up for air. In 1958, Vera Lynn was the biggest act on Decca; by 1965, it was The Rolling Stones. A revolution in culture had taken place, leaving, you’d imagine, appetites for bombastic 19th century German opera severely diminished. Not so. Culshaw’s gamble – which featured a little-known Hungarian called George Solti (pictured below, left, with Culshaw) conducting an orchestra initially unfamiliar to him, the Vienna Philharmonic, and a lead soprano, Kirsten Flagstad, who had to be lured out of retirement – sold like a pop record. According to Norman Lebrecht’s 2007 book, Maestros, Masterpieces & Madness: The Secret Life & Shameful Death Of The Classical Record Industry, it shifted 18m copies (a figure that presumably collects together sales of each of the four operas over the seven years), making it the best-selling classical album of all time. Others dispute that figure, saying that 1990’s Carreras Domingo Pavarotti In Concert (re-released as The Three Tenors In Concert) did better, but you get the point – not only was Culshaw’s The Ring a triumph of art (it’s twice been voted the greatest classical recording ever made, in polls for Gramophone and BBC Music Magazine), it also ended up in the homes of millions of people who had never considered buying tickets for opera, or couldn’t afford them. That was Culshaw’s dream. “The sickness of opera is that it is a very expensive and exclusive closed shop,” he wrote in a book about the recording.

And there’s another story here, too, of how The Ring made Decca’s name as a classical music label. Or, more specifically, how it raised a middle finger – in a very British fashion, mind – to arch competitor EMI, and particularly their own in-house super-producer, Walter Legge, the self-proclaimed ‘Pope of Recording’ who made a jaw-dropping 3,500 recordings for EMI and, as people used to say, a similar number of foes.

In 1962, producer George Martin signed The Beatles to EMI. Famously, Decca had already turned them down, but they bagged The Rolling Stones instead, creating in the public imagination a rivalry between the two companies. It certainly existed. George Martin’s approximate opposite number at Decca, Hugh Mendl, once said of EMI that they had “all of the arrogance of the BBC without any of the education”, although he was friends with Martin and initially wanted to work for EMI. The bitchiness extended to classical music. On the night before sessions for The Ring began, Legge bumped into Culshaw in Vienna and asked him what he was working on. “Very nice. Very interesting,” Legge said. “But of course you won’t sell any.”

These days, both EMI and Decca have been sucked up into gargantuan uber-record company, Universal Music Group, but rewind to the 1950s and the two companies had distinct personalities, attracting different types of staff. “EMI was conservative, Decca radical; one British bulldog, the other slinky Siamese,” wrote Lebrecht. “EMI occupied a mansion in St John’s Wood [Abbey Road Studios]. Decca’s studios were eight bus stops north in Broadhurst Gardens, West Hampstead, an area thick with continental immigrants.”

The companies had been founded two years apart – Decca in 1929, EMI in 1931 – but EMI grew to become the bigger enterprise. Under its umbrella in the 1950s were three separate powerhouse labels – Parlophone, HMV and Columbia – and, by the end of the decade, it had acquired Capitol Records as its North American subsidiary. Decca, on the other hand, although a major player, was run by a single man, Edward Lewis, for an astonishing 51 years, from the establishment of the company until 1980, when it was sold to PolyGram days before his death. It had more of the feel of an independent label, but nevertheless made huge inroads into the American market, first under the name Decca (Lewis sold off his American arm in 1937), then with a new label, London, which Lewis launched in 1947 to sell British Decca records in the US, and also to license American music for the UK. (To complicate matters more, Decca also had sub-labels and other lucrative licensing agreements, but let’s try and keep this simple.)

Walter Legge, above, was born in 1906, left school at 16 and started out at EMI’s HMV in 1927 as a writer – of sleeve notes and for the company’s monthly magazine. A natural musician, although he never wished to be one, he moved into record production, moonlighted as a critic for The Manchester Guardian, and also showed an aptitude for business. In the 1930s, with the entire industry taking a hit after the Wall Street Crash, he successfully pioneered ‘subscription’ recordings – proto-crowdsourcing, essentially, that ensured upfront funds were available to make records, and also brought in considerable profits.

He had brilliant ears, but terrible eyesight, and it prevented him from serving during the war. Cannily, he spent it directing the classical music side of the Entertainments National Service Association (ENSA), which put on concerts and programmed broadcasts for the troops. It was desk job, but one that allowed him to keep track of the exact whereabouts of Britain’s best orchestral musicians (many of whom were in the safe haven of the RAF’s symphony orchestra) and monitor their progress during the war years. Then, in one of music’s great land grabs, and by “investing every penny I’d ever saved or inherited”, he offered the cream of these musicians jobs in his own, new orchestra, the Philharmonia, which he founded in 1945 primarily as a recording outfit – a symphonic-sized, classical music version of The Wrecking Crew, if you like, or The Swampers, Muscle Shoals’s house band.

This was quite a ruse. Because Legge owned the orchestra, EMI would have to pay him royalties on records they appeared on, and he’d also been promoted to run the Columbia arm of EMI’s operation, meaning he could commission his own players. But he wasn’t done yet. To sell records, he needed famous conductors and singers, and suspecting – correctly – that there would be rich pickings of German and Austrian stars floating around in post-war Vienna lacking reliable work, he shot off to the still-occupied city in early 1946, this time to spend EMI’s cash. Incredibly, he signed Wilhelm Furtwängler, conductor of the Berlin Philharmonic between 1922 and 1945, his young rival, the fast-rising Herbert von Karajan, and a dozen quality vocalists, including the bombshell German soprano Elisabeth Schwarzkopf.

All three were controversial characters. Schwarzkopf and Karajan had been members of the Nazi Party; Furtwängler never joined, hated them, but had stained his reputation by conducting concerts for their top brass. Legge, a Germanophile who liked to shock, didn’t care. When Karajan started at EMI he was still banned from performing publically, so Legge argued – successfully – that studio work was a private business affair. Karajan and Furtwängler were subsequently cleared by tribunal; Schwarzkopf, below, became Legge’s second wife and a British citizen in 1953.

Effectively, Legge took extreme advantage of the chaos thrown up by the conflict to assemble an elite squad of musicians, ready to be guided by his supreme gift for production. He fully intended to dominate classical music recording in Britain for decades to come and, instincts sharpened by a penchant for benzedrine, he quickly proved to be a fierce competitor, even with EMI’s other labels. As George Martin recalled in his 1979 book, All You Need Is Ears, if Legge heard that Parlophone were about to record a piece he believed might sell, he’d bullshit them, say, “Awfully sorry, old chap – I did that last month,” and quickly summon Columbia’s team.

He can’t have imagined much of a challenger in Decca, the only other UK label to survive the war in decent shape. They had shown some chops for classical music in the 20s and 30s, releasing pioneering works by contemporary British composers like Frederick Delius and William Walton, but their core business was pop. When a 22-year-old John Culshaw first got a job at Decca in 1946, they had pianist Clifford Curzon, contralto singer Kathleen Ferrier and the composer Benjamin Britten on their books – all huge talents – but lacked a full roster of bankable stars and even an orchestra that could compete with Legge’s crack Philharmonia. So, like EMI, they went on a signing frenzy, called up their éminence grise in Zurich, Maurice Rosengarten (nicknamed Uncle Mo, and something of a Walter Legge figure himself), and told him to get to work. He delivered in spades, securing the services of three orchestras – the expensive-but-superb Vienna Philharmonic, Amsterdam’s Concertgebouw and Swiss conductor Ernest Ansermet’s Orchestre de la Suisse Romande – as well as promising individuals, including a pianist with aspirations to conduct, George Solti.

In a very different way to Legge, Decca also had a productive war. Highly capable sound engineers from the label had served in the Royal Navy as technicians tasked with creating equipment that could detect and catalogue German submarines by their signature engine noise. They brought their expertise in what amounted to high fidelity back to Decca’s studio, invented what became a trademark – full frequency range recording, or FFRR in short – and started releasing 78s that were miles ahead of the curve in terms of how good a record could sound. In the late-40s, they were quick off the mark to embrace the long-playing record; 10 years later they jumped on stereo. And this aptitude for, and love of, technology undoubtedly helped Decca to steal a march on EMI.

Not only was Legge a technophobe, he worked for a company that was afraid of seizing the future. They were late on the LP, late on stereo, and they never learned their lesson, completely underestimating the massive financial opportunity that the CD offered record companies when it turned up on the market in 1982. It was a stuffy, hierarchical organisation, where, as you’ll know from photographs of George Martin in the 60s, producers wore suits and most people worked banker’s hours. Decca was different. The boss, Edward Lewis, had Catholic tastes, but under him there was a democratic, family atmosphere, leading to the staff base being dubbed ‘the Decca boys’.

“‘The boys’ is how musicians talked about Decca – whether for its practical mechanics, its puerile idealism, or its preponderance of homosexual men at a time when gay love dared not speak its name,” said Lebrecht. “Discretion was the norm for gay men in the arts, but Decca was a safe house, as out as it was possible to be. Gordon Parry [engineer on The Ring and countless other records], pink-blond and perpetually on the prowl, was flagrantly bisexual. In the Decca apartment above the Sofiensaal [where The Ring was recorded], he went pounding on bedroom doors at night crying, ‘Come on beau! It’s only a bit of mutual masturbation!’” (Legge, on the other hand, used to call gay men ‘175ers’ – a Nazi-favoured reference to Paragraph 175 of the German criminal code, which made homosexuality a crime.)

There are a couple of pre-stereo Decca recordings that have gone down in legend – the Orchestre de la Suisse Romande playing Stravinsky’s Petrushka in the late-40s, and a 1955 album of the Vienna Philharmonic (and singers) performing Mozart’s The Marriage of Figaro conducted by Erich Kleiber, father of Carlos, who I covered in a previous Junk Shop Classical column. They must have taken Legge by surprise, but he was also on top of his game at this period in time. Furtwängler said of their landmark 1952 recording of Wagner’s Tristan And Isolde with the Philharmonia, “My name will be remembered for this, but yours should be,” and, just last year, The New York Times posited that a 1953, Legge-produced double LP of another of his star signees, the Greek-American soprano Maria Callas, singing in Puccini’s Tosca at La Scala in Italy was “the best opera recording ever”, not John Culshaw’s The Ring.

Culshaw’s era of excellence at Decca began after he returned to the label from a two-year sojourn at Capitol Records between 1953 and 1955. He’s best-known for The Ring, but believed his greatest achievement was a 1963 recording of Britten’s War Requiem, also a massive-seller. He clearly had a job for life at Decca, but he became irritated with the company in the mid-60s, concerned that it was losing its cavalier spirit, and went to work at the BBC in 1967 as its head of music programmes. He died in 1980, aged 55, of hepatitis. “To meet John Culshaw for the first time, quiet, charming, sharp-eyed but with no signs of aggressiveness about him, was to marvel that here was one of the two great dictators of recording art,” wrote Gramophone magazine in their obituary. “He transformed the whole concept of recording.”

The other dictator was Legge, and although the two men have been remembered as wildly different characters, they actually have much in common. Both started out as writers (Culshaw published two novels in the early-50s) and either might have said, as Legge did, “I thought of myself as a man determined to achieve certain standards, and not to be deflected by anything, or anybody, from those standards.” Legge also warred with his label, and in 1964 he sensationally tried to disband the Philharmonia. There was a stand-off with its music director, Otto Klemperer (Hebert von Karajan had left for German label Deutsche Grammophon in 1960), which Legge lost, so he resigned and left in his memoirs the following searing assessment of corporate culture in the record business: “I am convinced that in the arts, committees are useless. What is necessary are people like Karajan, Culshaw and me; we know not only how to achieve the best artistic results but how to attract the public and carry out the whole operation with carefully chosen collaborators. Democracy is fatal for the arts; it leads only to chaos or the achievement of new and lower common denominators of quality.”

He must have expected a big job after his reign at EMI – head of the Arts Council, perhaps, or running The Royal Opera House – but he didn’t get one, nor was he ever formally honoured for his significant contribution to culture in the UK. Culshaw wasn’t either, but Legge’s wife Elisabeth Schwarzkopf became a dame in 1976, despite her Nazi past. She would constantly say that her husband – a self-made man – was stiffed by the British establishment, and EMI. They got their revenge on the latter, at least. Just before Legge died in 1979, he produced Schwarzkopf’s final recordings, which were released in 1981 as To My Friends, an album on Decca Records.