A lot happens on Twitter, most of it utterly inconsequential. My compulsive need to trawl down the feed absorbing microscopic packages of useless information knows no bounds. But occasionally I stumble across something which gives pause for thought. A couple of weeks ago, DJ Ben UFO, darling of the UK’s hesitantly-termed ‘post-dubstep’ scene, flagged up a comment made by music journalist Kristan Caryl. Caryl writes for DJ Mag, Mixmag and Resident Advisor, among others. He was replying to the following tweets from another figurehead of the dance music underground, Paul Rose aka Scuba:

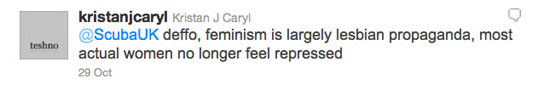

And Caryl’s even more objectionable response:

Now I should be clear that I’m no academic feminist. The more nuanced debates that surround issues of gender identity and equality are mostly lost on me. The internal differences which fall under the umbrella term ‘feminism’, the numerous gradations in ideology, are largely beyond the limits of my knowledge. Nor would I claim to speak for women – they do that themselves. But it’s important, when you see a wrong being done, to point it out. It seems to me that the criticism quoted by Rose is a tool of the backlash against feminism which is as old as the hills. It’s built on the assumption that gender inequality is non-existent, a thing of the past, and it stems from kneejerk defensiveness – feminism is equally as ‘controlling’, as prejudiced, as it claims dominant culture is towards women. In a nutshell: ‘you’re just as bad as us so you’ve no right to complain’.

Caryl’s response is more or less a framing of the same sentiment, albeit in terms that are rabid and misguided almost to the point of self-parody. The equation of feminists with lesbians is a stalwart of the repertoire. ‘Actual women’, one would assume, are women who agree with him.

I won’t go into too much depth as to why these comments are offensively incorrect, as I’m sure there are other people who could express it far more eloquently than me (and hopefully it’s self-evident). Put simply, it seems extraordinary that, in spite of plenty of structural evidence that women continue to be treated as secondary citizens, the view that feminism is a redundant ideology peddled by half-crazed lesbians still holds so much sway over mainstream discourse.

But why single out these tweets, and the sadly not-so-uncommon sentiments they express? Why go to the effort of plucking them out of the vast, turgid river of prejudice and abuse which flows past our computer screens on a daily basis? Caryl’s comment bothered me more than your usual online differing-of-opinion. Because although I’ve never met the guy or spoken to him, here was somebody deeply embedded in the underground dance music culture which I spend the vast majority of my time thinking, talking and writing about. I’ve got a lot invested in this culture – as have many others – and I like to think that it lends to its participants a shared, if loose, ideological framework. It was dismaying to find that an implicit disdain for women could sit comfortably alongside a love for underground dance music – because, although perhaps it’s not immediately obvious, the politics at the core of dance music culture lean the opposite way: towards an ethos of equality and inclusion which seems increasingly obscured or forgotten about.

In fact, when UK dance culture first exploded – with acid house and then rave in the late 80s and early 90s – its political charge was difficult to define. If anything, it seemed stubbornly a-political – a lifestyle built around mindless hedonism, an escapist creed for the disaffected youth of post-Thatcher Britain. From the outside, it’s easy to see why rave was often viewed as a negative phenomenon: not only because of our deeply ingrained distrust of bodily pleasure passed down to us from the Puritans, but also because these kids didn’t seem to stand for anything. Where 60s musical counterculture existed in symbiosis with the civil rights movement, and even the savage anti-establishment sentiments of punk had a clear political bent (albeit one which bordered on the nihilist), rave made no discernible statement. It had precious few coherent lyrics to build meaning around, and no outspoken scene figureheads. Its only direct friction with the authorities was over the 1994 Criminal Justice and Public Order Act – in other words, the only thing ravers deemed worth fighting for was the right to their own de-politicised spaces, where they could carry on undisturbed.

But to write dance music culture off as disengaged from its political surroundings is to miss the point. The DJ-led social-dancing model, germinated in David Mancuso’s Loft parties in early 70s New York, was a hugely important site for countercultural activity in the US. Throughout the heydays of disco, house and techno, clubs were places where working class, gay and ethnic minority groups could enjoy a freedom of expression denied to them in the ‘outside’ world.

In the UK, rave’s major contribution to the club dynamic was ecstasy. The highly erotically charged ‘togetherness’ of disco and house (legendary New York gay club The Saint featured a bespoke sex balcony) gave way to an almost totally sexless dancefloor vibe – E made ravers loved up, but not in that way. Loose-fitting, form-disguising clothes became the norm as ease of dancing in sweaty environs took priority over snaring a prospective partner. The ‘meat market’ often attributed to mainstream club culture, an environment structured for the male gaze and which tended to make women feel vulnerable and exposed, was totally undermined.

Theorists picked up on this aspect of rave. The dancefloor has been variously posited as a site of pre-oedipal Jouissance – its womb-like qualities of darkness, warmth and tactility allowing people to access a state prior to fixed gender roles – or as post-sexual, a mutually confirming assemblage of human and machine; a cyborg. The former is borne out in the dummies and other infantile imagery adopted by ravers; the latter in the post-Kraftwerk fetishization of technology (‘Man-Machine’) which runs through dance music culture like a binding glue. Either way, it became clear that the political value of the dancefloor was in the construction of a social space where the rigid divisions of dominant culture ceased to apply. Gender, sexuality, race – they were irrelevant when subjected to the carnival of sound, light and substances.

It’s not just a couple of offhand comments on Twitter which make this ideal seem pretty distant in 2011. It’s fairly common these days to see images of conventionally attractive women being used to promote music from a scene which is supposedly mistrustful of ‘image’ – either on record covers or, in an increasing trend, accompanying fan-uploaded radio rips on YouTube, where previously a shot of a white label record would have sufficed. Don’t get me wrong – I’m sure the perpetrators would turn their noses up at Page 3. This is soft porn with a sheen of arty respectability – what Ben UFO half-jokingly referred to as the ‘American Apparel-isation’ of the UK scene – a subtle but insidious objectification of women, drip-fed into the hipster milieu via topless photo shoots in VICE, which nonetheless treats mainstream ‘lad’ culture with disdain.

Elsewhere, in the higher stratosphere of commercial dance music, the recent DJ Mag top 100 failed to feature a single woman in amongst the David Guettas and Tiestos. Magazine editor and regular London Fashion Week DJ Hanna Hanra had a crack at the ‘boys’ club’ of international DJing in The Guardian, but shot herself in the foot with a ridiculous comment about women being unable to carry those heavy bags of vinyl – propagating the tired line of argument that women’s inalienable physical characteristics prevent them from participating in society on an equal footing with men.

Now clearly there are reasons, very deeply ingrained in our culture, why many more men than women choose to pursue a career in music – that’s a far larger issue than I could hope to tackle. But the association of the female form, tailored for the hetero-male gaze, with the music of a given scene – not to mention the mutual onanism of a male-dominated press – is clearly going to have an excluding effect on those to whom it’s not intended to appeal. As Ben points out, this is at odds with the ethos of much dance music – particularly the early house which is a touchstone for many current UK producers: “so many people are using early house music as a reference point, a movement with an important social and musical history geared towards creating a space for different lifestyles and different ways of living, and although the music is still essentially underground in terms of its sales and audience, the way it’s being presented and advertised now is closer to the mainstream than ever. If someone’s experience of dance music being released today is largely through YouTube rips, then the likelihood is that in a lot of cases they’re going to be listening to that music accompanied by imagery that wouldn’t look out of place in an American Apparel advertising campaign. To an extent I think it strips that music of the potential to speak to everyone, and that’s a huge shame given that inclusiveness has always been such a crucial part of this culture."

And this at a time when, I’d argue, we need the levelling power of the dancefloor more than ever. The fact is, we currently live in a society which is far more divided along lines of gender, sexuality, race, wealth and class than most people are willing to admit. We have the whitest, richest, most male-dominated cabinet we’ve had in years. And some large-scale sleight of hand gives comedians license to openly mock weaker members of society from behind a peeling veneer of irony. Somehow, the assumption that prejudice no longer exists, that we live in a near-mythically egalitarian society, has let that very prejudice sneak in through the back door – aided by the comfortable anonymity of online debate.

So what happened to rave utopia? This isn’t a simple case of decline, of a lost golden age. Every dance subculture the world over reaches its own compromise with dominant culture – is it fair to say that the ‘dress to impress’ ethos of UK Garage circa 2000 is inherently sexist? Or that Grime’s macho energy and testosterone-fuelled lyrical acrobatics should be dismissed as illegitimate because it appeals largely to young men? Obviously not. But there has been a visible trend, in the UK and elsewhere, away from the unprecedented sense of unity that the dancefloor can provide.

Perhaps it’s in line with the relentless onset of a Neoliberal ideology – set in motion by Thatcher and Reagan – which values the sanctity of the individual over any form of collective spirit. When there’s ‘no such thing as society’, where does that leave social dancing? Rave culture originally set itself up as the antithesis of this shift, but whether through co-option by commercial forces or a more general dispersal across the confused geography of contemporary culture, its boundaries have been eroded over the years, making the battle lines far less clear cut. It’s also harder and harder to find accessible urban spaces in which DJs and dancers can congregate to create this sense of togetherness – soaring property prices and the imperatives of real estate signalled an end to the illegal warehouse circuit which was rave’s backbone, in London and elsewhere.

The online infrastructure which has sprung up over the last decade – YouTube’s instant-access archive, the vastly accelerated hype-mechanism of the blogosphere, more novel innovations like the audiovisual spectacle of the Boiler Room – has the potential to liberate dance music from these constraints through connecting people in new ways, divorced from geography. But it can also cause harm. Ben voices a concern that music is now “so much less tied down to place, which fits comfortably with the prevailing attitude that music is ‘just music’ and that that’s its sole value – that the way it’s presented is of no importance if the musical content is the same." To embrace this is to deny the socio-political dimension of music – that which makes it 3D, gives it depth of meaning. Divorced from context and floating free in the ether, music is open to misinterpretation and misappropriation, whether malicious or simply misguided.

Now of course I’m not arguing that all fans of dance music undergo an epiphanic conversion to the cause of social change. I know as well as any the unpleasantly righteous fug which hangs over a lot of explicitly ‘political’ music – after all, it’s music that ultimately fascinates me, the actual sonic reality of it, not any attendant political cause which might be shackled to it after the fact, Live Aid-style. Music has political meaning woven into it the moment it is played, whether on a dancefloor or in a bedroom. And every act has political implications – whether it’s choosing what records to buy, which club to go out to, or how you dance when you get there. Having an awareness of the wider implications of the things we do – whether they might be ultimately harmful to the people around us and the scene we love – is surely no bad thing.

Sunday November 20th PLEASE NOTE: we’ve had to turn off the comments in this piece as for some reason they were crashing the page. This is NOT an attempt to end the very interesting debate that’s been going on, but a technical issue that we’re hoping to get resolved ASAP. Please feel free to use the Facebook comment function below. Many thanks.