Twa Books on a Bed

Friday July 15, 2022

Dear Reader,

I love corrugated iron.

One of the things that I love most about corrugated iron is that it does not love me. Or even give a shit about me.

When I was a child, we had a corrugated iron shed around the back of the house.

It was painted grey.

But it being painted grey did not stop it from being rusty as well.

There was nothing in this shed other than a lawnmower.

And an empty sack.

This corrugated iron shed did not have a window.

Some days I would go around the back of the house and sit in the shed with the door closed. This was the closest I could get to total blackness. Back then I did not know about aspiring to things, I did not know there were things in the world that we were supposed to aspire to. But if I had, I would have said, “I aspire to total blackness.”

Sometimes I would climb into the empty hessian sack and pretend that I was a stowaway on a ship going to far off lands.

The floor of this corrugated iron shed was concrete. In this concrete floor were three wandering cracks. These three wandering cracks all came together. Where they came together there was a very small hole. This small hole was just about big enough for me to put the middle finger of my right hand into. I used to try and imagine that this was the entrance to another world.

One day there appeared in the wall of this corrugated iron shed a small hole. I didn’t know how or why. But what I did know was that through this small hole the light came in. I did not want the light to come in. I wanted the total blackness. So I put the middle finger of my right hand into this small hole and it stopped the light coming in. This was good. But what was better was the feeling of the torn iron around the edge of this small hole scratching the sides of the middle finger of my right hand, as I pushed my finger into the hole. Sometime after tea, I would go out to the back of the house, so that I could be in there alone and put the middle finger of my right hand into this hole and feel the skin on my finger being scratched, while the blackness closed in around me.

Some days I would sit there on the floor of the corrugated iron shed, not being able to make up my mind which hole I should put the middle finger of my right hand into. I wanted to do the one on the floor that led to the other world, but if I did that, the light of this world still came through the hole in the wall of the corrugated iron shed. But if I put my finger in the hole in the wall of the corrugated iron shed, I did not feel close to the other world underneath this one.

Sometimes, when I was sitting in my corrugated iron shed, with the door closed, in the total blackness, with the middle finger of my right hand in the small hole, it would begin to rain. Nothing has ever sounded better than the rain on a corrugated iron roof. Nothing more threatening, exhilarating, life giving and life taking all at the same time.

This was in the late 1950s when I was about seven.

By the time I turned nine in 1962, I had learnt that there were things in the world we were supposed to aspire to. Josie Nicholson’s dad, who owned the Cree Mills, also owned a pale green Bentley. I was told by Angus McKey that this Bentley was one of the things in the world we should aspire to. I didn’t know why Angus McKey thought this.

Now that I was ten, I was bigger and had learnt how to climb. And what climbing was for. I could go around the back of this corrugated iron shed, where there was a very steep bank. And I could pull myself up between the bank and the back of the corrugated iron shed and then haul myself up onto the steep apex of the roof of the corrugated iron shed. And there I would sit, looking out at the world. It was while I was sitting up there staring out at the world that I discovered what I would aspire to in this world. And that was…

When I grew up, I would live in a house made of corrugated iron. And I could either sit on the concrete floor inside my house in total darkness listening to the rain, or I could sit on the apex of its roof and stare out at the world.

But…

One day I wanted more from life than just sitting up there staring out at the world. I wanted to be part of that world, like the rooks who had the rookery in the woods across the road from our house. So, I decided I would slide down the corrugated roof and over the edge. And then I would fly. I already knew I could fly, because I flew in my dreams. It just needed me to slide down this roof and off the edge to get me to fly in the world that was not in my dreams.

On this day that I was going to fly for the first time in the world that was not in my dreams, I was wearing my brown corduroy trousers. They had been made for me by one of the old ladies in the Kirk. I liked my brown corduroy trousers.

I started to slide. The parallel ridges in the corrugated iron were perfect for sliding down. But just as I was getting to the edge of the roof of the corrugated iron shed and about to start flying, a turned-up corner of one of the sheets of the corrugated iron caught my brown corduroy trousers.

The next thing I knew was, I was hanging upside down from the edge of the roof of the corrugated iron shed. Bellow me, several feet away, was the ground. Above me were the flock of rooks heading home to roost. And I could hear my brown corduroy trousers begin to tear. And the turned-up corner of this sheet of corrugated iron also began to tear into the inside of my left thigh. And it may have taken hours, or it may have taken seconds. Or maybe even just fractions of a second, but I was not flying, I was falling, and the ground smashed into me. And I lay there on the ground in silence. All I could hear were the rooks gathering for the night. And I put my right hand between my thighs, and the middle finger of my right hand between the tear of my brown corduroy trousers and into the tear in the inside of my left thigh. And I could feel the blood begin to flow. And this felt good. Almost better than flying.

Bill Drummond, photo by Tracey Moberly

I am lying in bed now. It is almost sixty years later. I am not flying. I never did learn to fly. Even though sometimes I still fly in my dreams. But the same middle finger of my same right hand is under the covers feeling the scar down the inside of my left thigh. I can hear the first drops of rain hitting the roof above me, as in the roof of our loft conversion. Outside, I can hear the chuckle of a pair of jackdaws. Sadly, the roof is not made from corrugated iron and there are no rooks in this part of suburban north London, but the jackdaws do just fine. I never got that corrugated iron house that I aspired to.

This rain sounds good, as do the chuckling jackdaws, but none of it sounds as good as the far off rain on corrugated iron and rooks gathering for the night.

And…

With the wisdom of those almost sixty years and counting, I have decided that that moment early on the Friday evening of October 5, 1962, when I was hanging upside down but before the beginning of my fall, was the very moment when the sixties began.

It was also the moment that my relationship with corrugated iron was sealed for life.

Right now, my mind and my body are being battered by Covid for the first time. I thought I was immune. I thought I was above it. I thought it was for others. But as I lie in bed, with the middle finger of my right hand under the covers touching the scar, as in that very mark in the universe where the sixties began, I am also thinking about where it ended.

As in…

We all know where the sixties ended. And why it ended. It ended in Hyde Park on the July 5, 1969. And it ended because a cabbage white butterfly landed on my left thigh, and I used the middle finger of my right hand to squash this cabbage white butterfly dead. And if the camera were to pull back, you would see that I was one of tens of thousands of young people sitting in Hyde Park watching Mick Jagger of The Rolling Stones, dressed in what looked like a white dress, emptying a box of cabbage white butterflies after reading those lines from Shelley for Brian Jones, who had died the day before the day before, but before Charlie Watts counted the band in and Keith Richards hit the opening chord to whatever their opening song was to be.

It, as in the sixties, ended there and then because I killed that butterfly. And The Rolling Stones were dull and boring and over and done with. And I walked away before they finished their set. But while I walked away, what was playing in my head was ‘21st Century Schizoid Man’ by King Crimson. For me, this was the first song of the beginning of the 1970s. As I was leaving Hyde Park, I saw a newspaper lying on the ground. I picked it up. It was called The International Times. I thought it must be like The Times, that the men in bowler hats read. But it wasn’t.

Over the following two years my relationship with corrugated iron was renewed and became more intense. Mid-to-late teens is a good period in life to have intense relationships. And corrugated iron is almost the perfect match to have a one-way intense relationship with. I feel sorry for the kids today that don’t seem to have corrugated iron, or even hessian sacks to hide in. Just TikTok. Nothing tears you like corrugated iron.

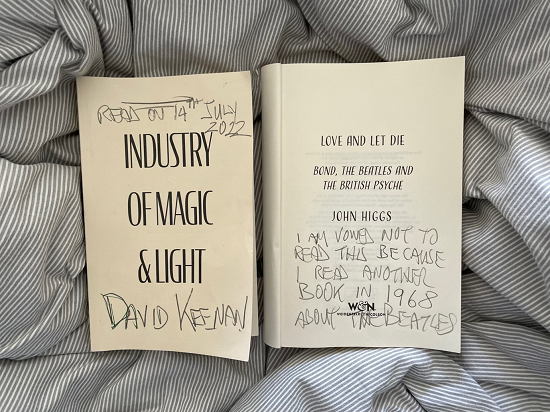

And if the camera were to pull back to show me lying on my bed on this July day in 2022, you would see beside me a copy of Industry Of Magic & Light by David Keenan. And a copy of Love And Let Die by John Higgs.

Both of these books have been posted to me separately by their separate editors, but both have been sent from the same publishing house to this house that I am living in that is not made from corrugated iron. And both these books arrived in the post yesterday, as the jackdaws chuckled.

David Keenan by Heather Leigh

This letter to you, dear reader, is not a commentary on these books, let alone any sort of review. This letter to you is my response to them lying on my bed while my body is being battered by the Covid.

In September 1968 I read Hunter Davis’ biography of The Beatles. After reading it, I signed an oath to never read another book about The Beatles ever again. I may have broken many other oaths, but I have never broken that one. That Hunter Davis book, along with On The Road and of course The Bible, are the trilogy of books that have had more influence on my life than any others. And that will not change. That book on The Beatles by Hunter Davis was the beginning of the end of The Beatles for me and the beginning of a whole new ocean of possibilities.

Also…

There is too much of my own lived 1960s in my head for me to cope with reading other people’s versions of what happened through those years. My brain filters are stained enough as it is.

As for the other proclaimed subject matter of the Love And Let Die book – James Bond. I hate James Bond and I hate franchised films and I hate fast cars and I hate Bond Girls. And who the fuck would want to have as an icon a man who chooses to wear a wig? Okay, a toupee.

Anyway, James Bond never drove an Aston Martin, he drove a pale green Bentley like Josie Nicholson’s father did.

These two books lying on my bed, and the Covid that is battering my head and body have triggered me into writing what I have written above.

I might not be able to read Love And Let Die, but I have read John Higgs’ ode to Watling Street. It is a great book. Reading books about roads and being on them is something I have always been drawn to, be it the many roads out of Corby, or the road to Damascus, which I seem to have spent most of my life on, waiting for that moment.

Before I started writing this letter to you an hour or so ago, I had spent the sporadic waking hours of the last 24 reading Industry Of Magic & Light by David Keenan.

My mind might have been in no condition to be taking anything in, let alone attempt to read a David Keenan novel, which by its very definition would have no comfortable narrative to hold your hand as you read the lines and turned the pages.

But the words in this book were taking me back to a dark period in my life, back to when I was 16 going on 17, back to 1969 into 1970 and on into 1971. Back to being on the road and back to corrugated iron .

Industry Of Magic & Light, or at least the first half of it, is set in a Scottish town called Airdrie. Airdrie has much in common with the Scottish town that I was living in from 1969 to 1971. Except my Scottish town was called Corby and was in the middle of the English Midlands, even if 85 per cent of the population were Scottish and we were all steeped in the worst and maybe some of the best of what passed for Scottish culture at the time.

But…

Industry of Magic & Light, or at least the first half of it, is not actually set in that period, as in 1969 through to 1971. But it does explore the rubbish and remnants left in a discarded caravan. And these remnants and rubbish reflect so much of the life that I was living or attempting to live or rejecting in that period of time. It was as if this book had been written for me about a time that I am not aware that other people have written about before. This black hole. That even the middle finger of my right hand could not fill. Not even my whole arm could fill. Nor my whole body. I tried climbing through the hole, but I did not have the strength to do so. I blame Covid.

By the end of Saturday July 5, 1969, having got the train back from Saint Pancras station to Kettering and then the 254 bus to Corby, and having read The International Times from cover to cover, I knew the sixties was over. All that Kinks singing ‘Waterloo Sunset’ and Small Faces singing ‘Itchycoo Park’ and Beatles singing ‘Penny Lane’ were done, gone… Along with Carnaby Street, miniskirts, Twiggy, kaftans and The Stones themselves. All that Swinging London 1966 to 1968. All that watching rainbows. And watching The Avengers on TV.

DEAD!

London itself was dead.

I never wanted to go back to London in my life.

There was nothing there.

I wanted corrugated iron.

I wanted blackness.

I wanted to put not just the middle finger of my right hand into the hole, I wanted to put my whole fist into it.

I wanted intensity.

And I wasn’t getting it.

Or not the right sort.

Each generation has its voice.

The sixties had many voices.

Bob Dylan was only one of them.

Ray Davies was only one of them.

Mick Jagger was only one of them.

John Lennon was only one of them.

But there was no voice for this black hole that I wanted to put my fist into.

So, over a period of no more than two years, I went looking for it. I took myself off to festivals. I would hitch hike to them. Each one on a different road out of Corby. The first was the 1969 Isle of Wight one. The one with Bob Dylan.

But it wasn’t Bob Dylan or any of the other bands or singers up there on the stage wanting our attention and money and love that caught me, it was the corrugated iron fences that surrounded us all. The corrugated iron fences that kept us in and others out. This is when my relationship with corrugated iron came raging back.

The first thing I did was look through a small hole in the fence. I saw people outside wanting to look in. Then I put the middle finger of my right hand through the small hole in this corrugated iron fence, so I could feel it tearing my skin. Then I got my cock out and pished against this corrugated iron fence. Then I realised I was not the only one pishing on the fence. We were many. And when we stopped pishing on the fence we began to tear it down. And there were those on the outside tearing down the corrugated iron fence. And we ripped it down. And of course we cut ourselves while ripping it down. There has to be blood. There always has to be blood. What is the point if there is no blood?

And then I hitch hiked back across the roads of England to Corby.

The next year I hitch hiked on another road out of Corby. Then hitched North West across England on Watling Street to the Hollywood Festival up near Stoke. This was in May. The Grateful Dead were playing. I knew nothing about The Grateful Dead other than that they were the Kings of the Californian Underground. Well, they were boring, they were rubbish. California could keep their kings of their underground. They were living in another era, all that Woodstock shite. All that We are stardust, we are golden. And we’ve got to get ourselves back to the garden shite from last year, from the 1960s.

A new band called Black Sabbath were playing, they were something different. You could tell they had that black hole that needed filling with a fist. It didn’t matter that they were dull. They had the darkness that I was in need of.

What is this that stands before me?

Figure in black that points at me

Turn round quick and start to run

Find out that I’m the chosen one

Also, and this gets sort of strange, also on the bill was Screaming Lord Sutch. You might know Screaming Lord Sutch from the Monster Raving Loony Party that used to stand in all the by-elections. But before all that. Before The Beatles. Before The Stones. Screaming Lord Sutch had been an English rock and roll singer. His only ever hit was a version of ‘Jack The Ripper’. This record had been produced by Joe Meek. That Joe Meek. The ‘Telstar’ Joe Meek. The Joe Meek that was my first producer as hero. The Joe Meek who shot and killed his landlady where I used to catch the 393 on Holloway Road back in 2019, as in before I had my first brain seizure and I started to transform into being The Elderly Gentleman and yeah, Covid stopped me catching the 393 even if the brain seizures didn’t.

But…

Even though Screaming Lord Sutch only had one hit, he toured and toured the country and he never stopped. Fashions would come and fashion would go but like that art school dance, Screaming Lord Sutch was still there. Nothing could stop him. And he was always dressed up in something different. Sometime outrageous. Sometimes strange. Something desperate.

A rumour spread across those of us there at this Hollywood Festival, that was near Stoke and nowhere near Sunset Strip. The rumour was that Eric Clapton and John Lennon were going to turn up and play with Screaming Lord Sutch. Of course they didn’t.

But…

In David Keenan’s Industry Of Magic & Light there is a small local free festival. And on the bill of this small local free festival is this fictitious singer called Sinew Singer. Sinew Singer had been a rock and roll singer back before The Beatles and The Stones. He had made a few records in the early ‘60s but then nothing for years. But this Sinew Singer turns up dressed in the most strange and weird and creative and alarming stage outfit and does a set with some of the new and happening musicians from the then underground Airdrie and Coatbridge scene.

And in my Covid head this is Screaming Lord Sutch and I am back at Hollywood near Stoke, not near the Whisky A Go Go, and I’m wondering if John Lennon is going to come on stage in this book that I am reading. He doesn’t. And he didn’t. So, I went and found that hole in the corrugated iron fence to put the middle finger of my right hand in, then pish on, then we ripped the fence down, while Ginger Baker’s Airforce were playing. But José Feliciano was good. I always liked his version of ‘Light My Fire’ better than The Doors’.

Then I hitch hiked back down Watling Street, across England, back to Corby.

Next I hitch hiked out of Corby and then down Fosse Way, in a south westerly direction, back across England to the Bath Festival in June. The Floyd were playing. I loved their Ummagumma LP. It was the perfect soundtrack to me lying on the floor of my bedroom in Corby, with its curtains closed and its walls painted black. Watching them playing ‘Set The Controls For The Heart of The Sun’ was the ultimate. And what was even better, you could not see the individuals of the band on the stage. All you could see was their liquid light show swirling around the stage.

But then it was Led Zeppelin…

Led Zeppelin represented everything I was beginning to hate. I hated rockstars. I hated their poses. I hated the way they held the microphones. And I hated the wind in their hair. I hated their guitar solos. I hated their snakeskin boots with Cuban heels. I hated their belts with those buckles. I hated their silk scarves. I hated their crushed velvet flared trousers. And I hated their ‘chicks’ standing at the side of the stage.

This… this was not why I had bought, and read from cover to cover, every copy of The International Times that I came across.

So, I went and found the corrugated iron fence. And found a hole in it. And then I got my cock out and I pished on the fence. Then we tore the fence down. And then I walked away while Led Zeppelin were still playing. I hit the road and hitch hiked back up the Fosse Way, across England to Corby.

And then I hitch hiked from Corby across England to the next Isle of Wight Festival in August 1970. And Jimi Hendrix was playing, and he was shite. And The Doors were playing, and they were shite. So I pished on the corrugated iron fence, and we ripped it down. And then Jimi Hendrix and Jim Morrison died. They were dead. Had I killed them? Had we killed them?

And then I hitch hiked from the Isle of Wight back across England to Corby.

I hitch hiked on another different road out of Corby and up Ermine Street to one last festival. It was outside Lincoln. It was in July 1971, The Byrds were playing. This was a mistake. This was rubbish. They didn’t even have any corrugated iron fences for me to tear the skin on my middle finger of my right hand, or to pish on, or to rip down.

It was over.

But while it lasted, we had no real voices.

We had Edgar Broughton singing ‘Out Demons Out.’

We had The Plastic Ono Band singing ‘Revolution, Evolution, Masturbation, Flagellation.’

We had Ozzy singing whatever he sang on the first Sabbath album.

We had ‘21st Century Schizoid Man’ by King Crimson.

But none of it really worked.

None of it filled that black hole that my fist could no longer fill.

As for The Pink Fairies and all that London shite, they were just faking it in their loon pants and smoking dope in Ladbroke Grove squats.

We didn’t have a war in Vietnam to rage about.

We weren’t Black Panthers with a slave heritage.

We weren’t the kids on the Paris streets ripping up the cobbles in ’68.

We weren’t living under Franco in Spain.

We weren’t living under the Fascists in Portugal.

We weren’t living under the Junta in Greece.

We weren’t living under the shadow of the Soviet Union.

We had it easy.

We had the dole.

We could get jobs down the Corby steel works.

We could hitch hike where the fuck we wanted.

We could speak English.

We could go to art school.

We could pretend to be artists.

We could read The Lord Of The Rings.

We could choose to be vegetarians.

We could choose to grow our hair long.

We could form bands and play rock music and the world would listen.

We were the over-entitled ones, however much we put our fist into the black hole, however much we cut ourselves on the corners of the corrugated iron.

We had it easy.

We had – or at least I had – Van Der Graaf Generator but they were not enough, not loud enough, or violent enough. Or maybe not even dark enough.

All I could do was read On The Road and quit art school.

And dump the whole notion of rock music having any value.

As for rock stars, they were now worse than the aristocracy that I thought had been thrown overboard ten years earlier.

And over the years and the decades and the even more years, my loathing of what music festivals represented in my head has only grown. That wholesale commodification of counterculture. Especially when it came to Glastonbury. In my head Glastonbury grew out of what I was reacting against. And last week knowing that Paul McCartney was there singing those songs and those three hundred thousand people were there singing along with him, I could not understand how any of this had been allowed to happen. No one had thought to make a citizen’s arrest of Michael Eavis or Paul McCartney himself.

But then things got even worse or was it just more bizarre…

On Tuesday evening on the news, I’m watching this Penny Mordaunt, who I am told will soon be the front runner to be the new leader of the Tory Party, thus the new Prime Minister. And this Penny Mordaunt is telling us that Boris Johnson was like Paul McCartney at Glastonbury, singing his new songs that no one wanted to hear, because we all wanted to hear all the old Tory songs that everyone knew the words to like ‘Cut Taxes’ and ‘Small Government’ and ‘Less Immigration’.

Maybe this is what John Higgs’ book was going to be about.

Maybe this is the British Psyche.

But back…

Back to 1970…

Back through that darkness.

Back to my quest for total blackness…

There had been glimpses of something else…

Glimpses of something achievable that was better…

Glimpses of that light coming through the hole in our grey corrugated iron shed.

And I don’t just mean faking support for the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia.

Or having a Che Guevara poster on your wall.

I mean glimpses of something, here.

Actually in Corby.

Or at least near Corby.

It can be glimpsed in the first half of David Keenan’s book that I have just read.

In the debris found in the caravan in Airdrie, that had belonged to the Industry of Magic & Light, an underground performance art group who used a liquid light show and mirrors and projections and sound.

For me, this light was Principal Edwards’ Magic Theatre who were based on a farm just outside Corby.

Principal Edwards’ Magic Theatre were what we would now call a performance art collective, but then would have dismissed as a hippy commune. There must have been over 20 of these hippies living on this farm outside Corby. And they put on shows that used lights and film and dance and projections and music and noise. And I had never seen anything like it before. The influence of their shows has stayed with me and influenced me down the decades. And they were hardly any older than me at the time. Four years at most. But they did it. And they weren’t doing it in London. They weren’t sitting in a squat in Ladbroke Grove smoking dope. They were out here near Corby. If they could do it, I should be able do whatever it is anywhere. Fuck London.

Maybe I should make a film about Principal Edwards’ Magic Theatre. A dramatisation of their story, not the reality. Like this is a dramatisation of my story. More Love Island meets Ken Kesey. “You are either in The Theatre or out The Theatre.” You know, Furthur and all that. That is once I have the Poppies In The Field film made.

But then there is the second half of Industry Of Magic & Light by David Keenan. Reading this in the early hours of this morning as the full moon stared at me through the open window triggered another whole tirade of twisted emotions.

In the second half of the 1960s in Corby, I had two close friends.

One was called Donald Anderson. His family had come to Corby from Moffat in Dumfriesshire in 1961. It was Donald who had first introduced me to Jimi Hendrix in 1967. It was Donald who explained to me how Jimi Hendrix had fucked every one of the women posing naked on the gatefold sleeve of his album Electric Ladyland. It was Donald who asked me to do the window-cleaning round with him on Saturday mornings, which meant I earned enough money to buy the tickets to go to the festivals that I went to, so that I could tear down the corrugated iron fences.

The other friend was called Pete Calderbank. His family had not moved down from Scotland. His family had moved down from Barrow-in-Furness in 1962.

We, the Drummonds had moved down from our rural town in Galloway, Scotland in 1964.

It was Pete that I went fishing with and collected birds’ eggs with and hitch hiked to Barrow-in-Furness with. It was also Pete that showed me how to play my first chords on the guitar. It was Pete that told me about the book about The Beatles by Hunter Davis. It was Pete that I first drank a whole bottle of Strongbow cider with. And Pete showed me how to drive a car when we were not old enough to drive cars. And Pete went to art school with me in Northampton. But then after two days at art school, Pete had a car accident and he quit art school.

The next thing I heard was, Donald and Pete were driving from Corby to Australia, in a second-hand Land Rover that they bought with money from working at the steel works. But they only got as far as the Pakistan / India border. And they were not allowed to go any further. So, they drove back to Afghanistan and stayed there and did things there. Things that you could do then but not do now. Then they drove back further. But when they got as far as Amsterdam, Donald didn’t want to go any further. Donald did not want to go home to Corby. Donald has lived in Amsterdam ever since. Donald has made his living through trading in the “goods”. Pete came back to Corby, then Pete flew to Australia. Pete has lived in Perth, Australia ever since. Working in the building trade.

Pete Calderbank sitting on bumper. Donald Anderson standing next to him, in Afghanistan in 1970s

The last time I saw Donald was early in 1977, when I was over in Amsterdam with Ken Campbell and the Illuminatus play that I had done the stage sets for. I see Pete about every five or ten years when he is back over in the UK.

Their extended sojourn in Afghanistan has always held a place in my imagination. What they did there. The things they saw there. The food they ate there. The people they met there. And the thing is, that is where much of the second half of David Keenan’s Industry Of Magic & Light is set. At the very same time that Donald & Pete were there. As I turned the pages of David Keenan’s book, I kept hoping that Donald & Pete would turn up in it. But they didn’t.

But what did happen, is a Land Rover got stolen. I used to have a beat-up Land Rover. Had it for about 15 years. It defined so much of what I was doing in those years. Last night I had a dream where my Land Rover was stolen, not in Afghanistan but in some far-off land that only exists in dreams. And in this dream, I am driving around in my Land Rover looking for my stolen Land Rover. Then I turn up in Amsterdam at the flat where I last met Donald back in 1977. And then I wake up it is the middle of Wednesday night as in the very early hours of Thursday morning, as in yesterday. And looking back at me through my open window is the full moon. And it’s a huge orange supermoon, shining straight at me.

It was Donald & Pete’s journey to the East that shifted everything up a few gears, that and reading all of Kerouac, and Kesey and The Electric Kool Aid Acid Test, and Fear & Loathing, and all of Henry Miller, and Jack London, and Play Power, and The Female Eunuch, and all those other books that had to be read, if you lived in Corby. And hitch hiking from Corby to Portugal to join the Carnation Revolution, only to find it was all over by the time I got there.

There is another whole subplot in David Keenan’s Industry Of Magic & Light novel to do with a young man who boxes and takes amphetamines and is living in Tito’s Yugoslavia and then in West Berlin. As of now, I have not found myself in these pages. Maybe my life as an aspiring boxer in West Berlin is yet to happen.

*

I emailed all of this to David Keenan about twenty minutes ago, he texted me back within ten minutes. He had read the lot. He had issues or at least questions about the paragraph that you have just read where I said, “I have not found myself in these pages”. He said, what about the first page of Chapter 16 where Adam the aspiring boxer is taken swimming…

And I quote from the book:

We must learn to swim in the cold filthy rivers, he said as he led me down beneath a concrete flyover where someone had written the words Die Welt. Today is Die Welt Day. Pony said to me, and I said, what, and he said, nothing, then he ordered me to strip off and to dive in. There were splinters of wood floating in the water and glass bottles and plastic bags and God knows what else. I think there might even have been syringes on the ground. Get in it, he said. It stinks, I said, I’ll probably catch something from it, and he said to me, you have to pierce the veil, he said. The veil of what? I asked him. The veil of yourself, he said, and he shrugged, as if it was obvious, and I took a look at that brown dirty water, who knows what lies beneath, and I closed my eyes, and I held my breath, and I jumped in. And I never touched the bottom.

And David Keenan is saying to me in the text that he just sent ten minutes ago “isn’t that what you do or did in that Best Before Death film. Are you not seen submerging into the dirtiest, broken glass, rat infested waters under Spaghetti Junction with your graffiti on the wall behind you?” And David Keenan is right. But I wasn’t expecting this direct identification. And yes, I do think it is easy to go wild swimming in a crystal-clear mountain stream, but in life you have to submerge yourself into the shittiest grime, with the broken glass and plastic bags and drowned rats and with the thundering traffic above you. With complete uncertainty as to the outcome. And if you are not willing to do that, there is no point. Even though I was doing it in reality just to make some symbolic gesture. And I realised that these characters, as in this Adam, the boxer, and his trainer Pony, and his manager Coy are all somehow aspects of me. Or at least versions of me that I aspire to be. Anyway, enough of this divergence and back to the letter that I was writing to you before I had to cut in with this near future edit…

*

It is now the middle of Friday night. The moon is no longer full or super. I am drained, I can’t tell if it is the Covid hanging on in there, or I have just been doing too much writing and thinking and allowing corroded memories to batter me. But I can’t stop myself. Earlier this year I went to Galloway, to the town of my childhood in Scotland, as in not Corby where I spent my teenage years, but the one where I hung upside down. Under the cover of an early dawn, I snuck into the garden of our old family home. And I crept around the back. The shed was not there. It had gone. To a better life I hoped but…

I have just put “Corrugated Iron Shed” into Google. I don’t know if I am looking for one to buy and build for my garden up here in suburban North London, so that I can go and sit in it in the dark. Or maybe sit on its roof. Or maybe even slide down from the top of the roof to see whether, at this late stage in life, I still have a chance of flying. It seems there are all sorts of corrugated iron sheds that I could buy, but they all look too modern, and they all have windows and look too comfortable. But then I see a photo of an old rusty one. And I know that is the perfect one for me. But will I do any more than just copy and paste the photograph of it, to go at the bottom of this letter to you?

I don’t know.

We will see.

Yours Sincerely,

The Elderly Gentleman

Post Script:

In the opening salvo of this letter to you, Dear Reader, I claim that the day I was hanging upside down from the edge of the roof of our grey and rusting corrugated iron shed, was Friday October 5, 1962. Now, I know it was in 1962 but I have no idea which actual day of the week or month of the year it happened. I just used that date because that was the date on the back cover of John Higgs’ book Love And Let Die. The date he states that the first record by The Beatles and the first James Bond film were released. Thus, a good date, I thought, to hang the beginning of the sixties on. And it is.

But…

My sixties, in reality, did not begin for almost another eleven months. It began on my first day back at school in early September of 1963. We, the Drummond family, had been out of the country for three months, we had been living in a small town in North Carolina. While there we had been totally cut off from what was happening back in our Newton Stewart in Galloway, in rural South West Scotland.

What the ten-year-old me learnt on that first day back at school in early September 1963 from my best friend Sam Funia, was…

That there was this new thing called The Beatles, and they were bigger than Elvis, bigger than Celtic or Rangers, bigger than John Wayne, bigger than the Second World War, even bigger than Bannockburn. And all the girls in the world screamed at them. And all the newspapers in the world put them on their front covers. And even Akela at the Cubs loved them. Even Mr Gutcher our Headmaster warned us about them. And I had no idea what Sam Funia was talking about, but I believed him. That was the day that, for me, the sixties began.

Thus, not quite…

Between the end of the "Chatterley" ban

And the Beatles’ first LP.

My Ideal Home

David Keenan’s Industry Of Magic & Light is published on August 25 via White Rabbit. John Higgs’ Love And Let Die is published on September 15 via Orion.