There are plenty of classical music boffins who put Claude Debussy right up there – not above Bach, but in the mix with Beethoven and Mozart. He’s certainly France’s most significant composer – the stand-out in a crowded field that includes Hector Berlioz, Camille Saint-Saëns, Gabriel Fauré, Maurice Ravel, Lili Boulanger and Olivier Messiaen.

Like all great composers he transcended nationhood, although he called himself a musicien français. He was influenced as much by the writings of Edgar Allan Poe and the paintings of Turner as he was by music, and he liked music from all over – Russia, Indonesia, Vietnam. His own works were a new dawn – pioneering, highly original, and they had an enormous impact on what came after him, in classical music and beyond. Debussy is weaved into the fabric of jazz, pop, soundtrack and electronic music, and many greats over the decades have doffed their cap to this curious little Frenchman, from Duke Ellington to Steve Reich, John Williams to George Michael. There’s even a bonkers drum & bass mashup/concept album out there, The Seduction Of Claude Debussy, created in 1999 by Trevor Horn and Paul Morley’s synth-pop group Art of Noise, complete with a rap by Rakim and narration by John Hurt: “Eventually, Claude Debussy was recognised as one of the greatest composers of his time. Today he is more than that – he is considered not only the greatest French composer who ever lived; he is considered the revolutionary who set 20th century music… [dramatic pause] on its way.”

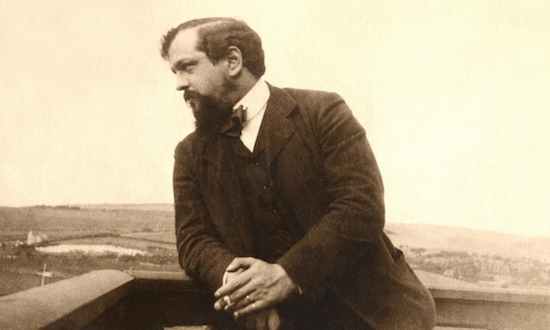

It’s true that his position in music has grown since he died 100 years ago on 25 March, 1918, of cancer, aged 55. His death – admittedly on the Monday after a weekend of Paris being battered from air and ground in the Spring Offensive – went largely unnoticed, with France still unsure about how good he actually was. We understand his brilliance now, but Debussy, the man, remains a tricky proposition. He was complicated, and contradictory. His radical music required new ears of its listeners, but it was instantly appealing and popular. He shunned the strictures of the conservatoire, but he was among the most musically educated of composers in history. His works are sensual and alluring, but in person he could be abhorrent and he was a shit to women. Two of his exes shot themselves, more of which later.

Here’s how Harold C. Schonberg describes Debussy in his excellent book, The Lives Of The Great Composers: “He always was abnormally touchy – quick to take offence, sensitive to the point of mania, uncomfortable with people he did not know. Naturally he hated to appear in public, hated to conduct, hated to play the piano at concerts. He preferred cats to people, and was never without one or more Siamese cats. Perhaps he saw reflected in cats the reserve, independence, and lack of morality of his own nature. Debussy did have the habits and morals of a tomcat, and there was something feline about the character of the man, though there was nothing feline about his physique. He was short, plump, flabby, pale, and indolent; he had heavily lidded eyes under his huge bulging forehead; he wore a beard that reminded many of Christ in Italian renaissance paintings. He trained his hair to hide the bulges, but it did not work, and he was called ‘Le Christ hydrocéphalique.’”

But Schonberg adds: “He was also born a genius with two of the most sensitive ears any musician ever had. No composer ever had a more infallible instinct for the one chord that would supply exactly the right touch of colour… From his exquisitely sharpened sensibilities came a new vocabulary. His was not the grand-themed music of Bach or Beethoven, and some of it is even precious. But in its taste, colour, and fragrance there has never been anything like it.”

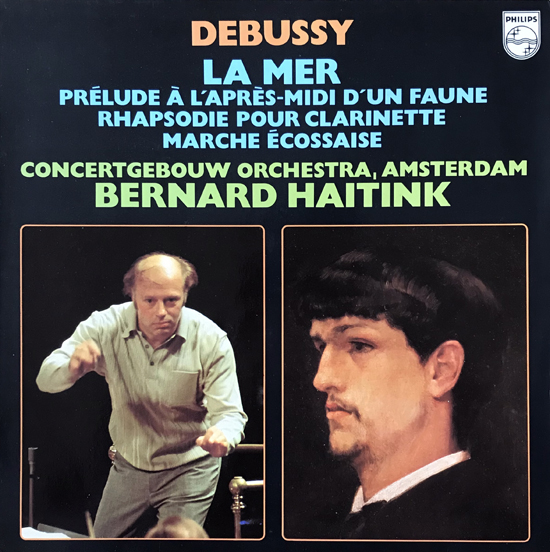

This famous record from 1977 finds Dutch conductor Bernard Haitink and the Concertgebouw Orchestra of Amsterdam playing Debussy’s breakthrough composition, 1894’s Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune, the symphonic La mer, and a couple of lesser-known pieces. It’s as good an introduction to Debussy as any, although you might equally start with Walter Gieseking playing his solo piano pieces (the two books of Préludes, Images, Estampes and Études). The piano was Debussy’s instrument, and he excelled at it from a young age. The eldest of five children, he was born near Paris in 1862, the son of a seamstress and china shop owner, began piano lessons at 7 and by the staggeringly young age of 10 had earned a place at France’s best music school, the Paris Conservatory, where he stayed for the next 12 years.

Debussy was a precocious youngster from a poor background and he felt strangled by the formality of the education at the Paris Conservatory (before which he’d been home-schooled). Against his parents’ wishes, he favoured composition above training to become a concert pianist – the more secure job – and although he showed immediate talent, he pissed about in class, refusing to fall in line. Nonetheless, he won prizes and towards the end of his time at the conservatory he conformed enough to win, aged 22, the most coveted prize of all, the Prix de Rome – a scholarship, essentially, to further study composition in Italy. Winning didn’t make him happy. “I can assure you my heart sank,” he wrote in a letter. “I saw clearly the anxieties, the tedium that the least official recognition fatally entails.”

Duly, he hated his time in Rome, complained about the other students, the weather (“frightful”), the food, the villa he was staying in (“abominable”), and also how impossible it was for him to follow his own creative urges. "I am sure the Institute would not approve, for naturally it regards the path which it ordains as the only right one,” he said. “But there is no help for it! I am too enamoured of my freedom, too fond of my own ideas!"

A professor at the Paris Conservatory once asked Debussy, “What rules do you follow?” He replied, “Mon plaisir,” meaning ‘what I feel’, and that applied to his private life, too. Aged 18, he started what became an eight-year-long affair with a much-older married woman, Marie-Blanche Vasnier (a singer), and before and after he went to Rome, he sucked up as much culture as he could in Paris, and beyond. According to Alex Ross’s book The Rest Is Noise, “Debussy sampled the wares of Paris’s avant-garde scenes, browsed in bookshops stocked with occult and Oriental lore and, at the Bayreuth festivals of 1888 and 1889, fell under the spell of [Wagner’s opera] Parsifal. He attended [symbolist poet] Stéphane Mallarmé’s elite Tuesday gatherings from around 1892 on, and also delved into more obscure regions – cultish Catholic societies such as the Kabbalistic Order of the Rose-Cross and the Order of the Rose-Cross of the Temple and Graal.”

We hear in Debussy’s first orchestral piece of note, Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune (Prelude To The Afternoon Of A Faun), an assimilation of the breadth of his interests and ambitions. It’s loosely based on an erotic poem by Mallarmé about a faun and his fantasies of two nymphs; it couples Asiatic moods with the materials of Western music (minor chords, suspensions, romantic harmonic language); and it also smashes through conventions of composition that had been standard for 100 years or more. A flute comes in, echoing the one that the faun plays in the poem, repeats its melody, and then, in contrast to what might happen in a piece of Germanic music from the era or before, the theme isn’t developed. The piece evolves in an unusual, free-flowing manner to create a dizzying and gorgeous kaleidoscope of sound more akin, as Alex Ross has it, “to Indian ragas than to Wagner or Strauss. It is the music of physical release, even of sexual orgasm.”

Debussy meticulously sculpted the ten-minute-long Faun between 1892 and 1894, by which time he’d shaken off the influence of the bombastic Wagner. He had become far more interested in the maverick works of Russian composer Modest Mussorgsky, who was self-taught and broke with every compositional tradition because of it, and his friend, the equally radical and eccentric Erik Satie. In fact, Satie had beaten Debussy to creating a new feeling for music with his perennially popular Gymnopédies from 1888. This piece achieved potency through simplicity and, along with Faun, did for classical music what punk managed to do for rock – uncluttered it and called time on pompous grandiosity (Wagner and prog rock respectively). This new music ensured, as the 20th century approached, that none of the old rules applied.

Harold C. Schonberg thinks the Faun has a place in music history comparable to Beethoven’s Eroica symphony. French composer Pierre Boulez said, “All of Wagner’s heavy heritage was discarded… The Debussy reality excludes all academism.” There were more revelations to come. In 1889, he had attended the World’s Fair in Paris, which marked the centenary of the French Revolution (the Eiffel Tower was built for it), and became transfixed by, first, the music of a Vietnamese theatre troupe, and then a performance of an Indonesian gamelan group at the event’s Javanese Village. Six years later, he wrote to the poet Pierre Louÿs and said: “Do you remember the Javanese music, able to express every shade of meaning, even unmentionable shades… which make our tonic and dominant seem like ghosts? Their conservatoire is the eternal rhythms of the sea, the wind among the leaves, and the thousand sounds of nature, which they understand without consulting an arbitrary treatise.”

Hearing gamelan music – an otherworldly percussive sound played on xylophones, bamboo flutes, gongs, bells and other instruments – had a profound effect on Debussy and he sought ways to incorporate it into his own music. As Howard Goodall explains in The Story Of Music, he did two things: made copious use of the pentatonic scale (the five notes that are common to all the world’s musical systems – found, most easily, by playing just the black notes on a keyboard) and he also “allowed his chords to hang over each other, overlapping and ricocheting from one to the next, rather in the way the different tones of bell-ringing overlap one another". The results, best exemplified by two short piano pieces – 1903’s ‘Pagodes’ (‘Pagodas’) and ‘Voiles’ (‘Sails’) from 1909 – were stunning.

Debussy’s piano works nearly always have descriptive titles, like ‘Sails’ or ‘The Girl With The Flaxen Hair’, and in no small part led to his music being called impressionism, as if he was creating the musical equivalent of a Monet or Renoir painting. He despised the term, and best explained what he was trying to achieve – something nearer to symbolism – when referring to Beethoven’s Pastoral symphony: “Certain of the old master’s pages contain expression more profound than the beauty of a landscape. Why? Simply because there is no attempt at direct imitation, but rather at capturing the invisible sentiments of nature. Does one render the mystery of the forest by recording the height of the trees? It is more a process where the limitless depths of the forest give free rein to the imagination.” He believed that pieces of his labelled as impressionism had a good deal more to say than being mere musical descriptions of whatever was mentioned in the title, and he was right. They can be transcendental – an experience in their own right – and that’s absolutely the case with La mer, which flopped on premiere in 1905, but it now considered to be one of his greatest (and most popular) works.

La mer is the closest thing to a symphony that Debussy wrote. Exhausted by Germanic music (Beethoven bored him, despite the above quote, and he had little truck with Schumann, Mendelssohn and Brahms), he declared that the symphony was dead, but he did make some concessions with La mer, calling it “three symphonic sketches for orchestra”. It’s a magnificent experience (and Haitink’s recording is thought by many to be the best) that begins with a movement titled ‘From dawn to noon on the sea’ and ends with ‘A dialogue of the wind and the sea’. Those are Debussy’s descriptions, and he also chose to have the famous woodcut The Great Wave Off Kanagawa by Japanese artist Hokusai printed on the cover of the score. But is La mer actually an impression of the sea? If you want it to be, sure, but it’s entirely abstract and perhaps as telling of its composer’s inner life as it is of any aspect of the natural world.

Debussy’s affair with Marie-Blanche Vasnier ended when he moved to Rome. When he returned to Paris he lived with a woman called Gabrielle Dupont (Gaby) for ten years, but he was unfaithful, firstly with a singer called Thérèse Roger, to whom he was briefly engaged, and then with a friend of Gaby’s, Rosalie Texier (Lilly) a fashion model. “I’ve had some troublesome business in which Gaby, with her steely eyes, found a letter in my pocket which left no doubt as to the advanced state of a love affair with all the romantic trappings to move the most hardened heart,” he wrote. “Whereupon, tears, drama, a real revolver and a report in the Petit Journal. It was all barbarous, useless and will change absolutely nothing.”

Gaby had shot herself, survived, and a similarly awful occurrence happened with Lilly when he left her for his second wife, Emma Bardac (a singer, intellectual and former love interest of Fauré’s), who was also married when they met. Lilly was devastated, shot herself in the chest while standing in the Place de la Concorde, lived, but the bullet remained lodged in her vertebrae for the rest of her life.

The second shooting, which took place in 1904, caused a scandal. Debussy became alienated from his friends and wider Parisian society. The couple fled to England, via Jersey, resulting in La mer being completed in Eastbourne, of all places, in summer 1905. While there, living for a month at the Grand Hotel, his divorce came through.

How much of this turmoil in his private life did Debussy inject into La mer? Impossible to say, but he cherished the unconscious mind’s power to drive creativity and he loved Edgar Allan Poe, not because he read him as a horror story writer, but because he saw him as delving into something beyond reality by using symbols – cats, dungeons, masquerade, rooms decorated black – of an unconscious life. Preternatural things certainly seem to happen in La mer’s third movement. “The freedom of Debussy’s music takes over, so it’s not the onomatopoeia of the music that counts, but the elements that are producing their own effects of reality,” said Radio 3’s Tom Service in a recent episode of The Listening Service. “The reality of this music is pitiless, terrifying, and what’s terrifying about it is that these uncanny swells and surges of musical material are unnatural. They’re being wielded by the composer. They don’t make shapes as predictable as a wave or a gust of wind – this music obeys its own logic; it makes its own rules. It’s a musical storm, not a maritime one, and that’s why it opens up new kinds of feeling for us listening.”

Despite the scandal, and the initial indifference that met La mer (the two things might have been related), Debussy’s career recovered. But he never made a great income. It’s been speculated that although Emma was a good match for him, and he doted on their daughter, he married for money. If he did, his plan backfired – Emma’s wealthy uncle cut the couple off, forcing Debussy to work as a (barbarous, of course) music critic as well as a composer. Many masterpieces followed La mer, especially his 1912 ballet Jeux, and he shocked his followers at the end of his life by writing six pieces (only three were completed) in an entirely traditional style – sonata form.

It’s crazy to think that when rectal cancer claimed him in 1918 he was poor and not yet thought to be a titan for the ages. That would happen as music in the 20th century took off down many different paths, profoundly influenced by his contribution. But perhaps Debussy knew something others didn’t, allowing him to see into the future with clarity. A fan of cabaret life as much as so-called high art, he picked a 20-year-old Charlie Chaplin out of an ensemble cast at a show in Paris and demanded to meet him, simply to say: “You are instinctively a musician and a dancer.” And although, in more recent times, he’s been accused of orientalism, equally he’s been praised for being, as Howard Goodall says, “part of a healing process that would gradually reunite all of the world’s musical cultures into one multitudinous (or dangerously homogenised, as some believe) mainstream.” That’s the reality of the 21st century and it may be that right now – 100 years after his death – we’re finally catching up with this impossible, visionary man.