Clara Schumann was a colossus of the piano in the 19th century – technically brilliant, exquisite musically, and she became famous across Europe, including in Britain, where she performed often. She also knew how to deliver a world-class diss. Then, as now, the music business was fierce and Clara had rivals, one of whom was a fellow German called Friedrich Kalkbrenner. Like Clara, he was also a composer. She saw a piece of his being performed in Paris when she was 19, didn’t think much of it, so she wrote the following to her father: “A sextet of Kalkbrenner’s was played yesterday, which is miserably composed, so poor, so feeble, and so lacking in all imagination. Of course Kalkbrenner sat in the front row smiling sweetly, and highly satisfied with himself and his creation. He always looks as if he were saying, ‘Oh God, I and all mankind must thank Thee that Thou hast created a mind like mine.’”

Plenty of other musicians were given stick by Clara over her long and eventful life. When she was young, she admired Liszt – the first musical matinée idol – then she turned on him, writing, “Before Liszt, people used to play; after Liszt, they pounded or whispered. He has the decline of the piano on his conscience.” (She also once had a pop at his fans after a concert: “The women were, of course, mad about him – it was revolting.”) About Wagner’s 1845 opera Tannhäuser, she said he “wears himself out in atrocities” and she was even more brutal about a later work, Tristan und Isolde, calling it, “The most repugnant thing I have ever seen or heard in all my life… During the entire Second Act the two of them sleep and sing; through the entire last act – for fully 40 minutes – Tristan dies. They call that dramatic!!!” As for Bruckner’s Symphony No. 7: “A horrible piece.”

These burns were written in letters or in her diary, which were gorged upon by music historians after Clara’s death at 76 in 1896 – more, judging from reports at the time, for what they revealed about the male musicians she knew (her husband Robert Schumann, Brahms, Chopin, Liszt and Mendelssohn). Nonetheless, in the 20th century, as appetites to learn more about female musicians from the past grew, a fuller picture of Clara’s character emerged, often at odds with how she was perceived in her time. Liszt called her a “gentle suffering priestess”; another contemporary, the English novelist George Eliot, said she was a “melancholy, interesting creature”. And you can understand why. Anyone who bought a ticket to see her play after 1856 would have known that Robert – now considered to be one of the 19th century’s greatest composers (thanks, in no small part, to Clara’s promotion of his music) – had gone mad, tried to kill himself, and died in an asylum, aged 46 (Clara was 36 at the time). Their son Ludwig also ended up being, in Clara’s words, “buried alive” in a psychiatric ward, and she outlived three more of the eight children she had with Robert. (Catastrophe in the Schumann family continued long after her death. In researching this article, I stumbled upon a curious New York Times story from 1941 detailing how a grandson of Robert and Clara’s, Felix, had taken his own life in upstate New York because of “poor health and financial reverses”. He’d been working as a house-to-house lingerie salesman.)

Clara, who picked up an instinct for commerce from her dad, knew how to pull a crowd. When she was young, she combined virtuosic brilliance with a kind woe-is-me wistfulness, which added, Anna Beer writes in a recent book on women composers, Sounds And Sweet Airs, “frisson to her identity on the platform”. Later, she understood that being known as a tragic heroine was good for business, but she never faked it. In 1872, she wrote, “It often seemed to me – and still does – that when I played, my overburdened soul was relieved, as if I had truly cried myself out.” She’d perform, exorcise her demons, then get back to meticulously managing her off-stage affairs, which meant not just caring for her family but masterminding her own career. A child prodigy who achieved success young, she always worked, acted as her own agent and publicist after she fell out with her father, and she was canny with money, especially after Robert’s death. “She not only invested in securities herself; she also took care of the investments of her close friend Brahms,” writes Harold C. Schonberg in The Virtuosi. “Like all careful money managers, she invested only in triple-A securities, satisfied with a return of 4 to 6 per cent. She wrote to Brahms on 6 May, 1867: ‘I have bought for you three Rhineland Railway shares in Cologne for 750 thalers… I should like to have bought 1,000 thalers’ worth of securities for you, but I did not know whether you would like me to, as I should have to pay 12,000 thalers for them. They are now standing at 111 and in good times 120 and over, and pay 6.5 per cent.’”

It was a smart investment. The shares shot up, bagging Clara and Brahms a dividend increased to 10 per cent. (As I mentioned in a previous column on Brahms’s German Requiem, their relationship was the most significant of his life, although, as far as anyone knows, it was platonic.)

In a different book, The Great Pianists, Schonberg says that Clara was “the most important ‘classical’ pianist of the 19th century”, meaning she was the traditionalist to the century’s firebrands and progressives, like Liszt. But it wasn’t like she sat on old repertoire. Of the four composers she most favoured at the 1,300-odd concerts she performed in a 60-year career, three were contemporaries – Mendelssohn, Chopin and Schumann (the fourth was Beethoven, who died shortly after she was born) – and she’s credited with playing a major role in bringing their music, and Brahms’, to wider attention, changing the public’s taste in the meantime. And, in her own way, she was just as revolutionary a pianist as Liszt, pioneering two things we’ve long taken for granted in classical music – the solo recital and playing from memory.

“Although Liszt had been the first to give unaided solo recitals, it was Clara who even more than Liszt broke the 18th century format,” writes Schonberg. “Up to about 1835 the artists generally had to engage an orchestra, was expected to play his own music with it, had to arrange for guest artists to share the programme, had to vary his programme with short pieces, had to end with an improvisation. But by 1835 Clara was, for the most part, playing with just a few assisting artists, and moreover presenting nothing but the best.”

It was a Polish composer and professor called Theodor Leschetizky (1830-1915) who maintained that Clara was the first pianist in history to play without the music, a practice that only started to become standard from about the 1850s onwards. Previously, it was considered poor form, as if the pianist was disrespecting the works of great artists. Duly, Clara was criticised for being an upstart, including by a friend of Beethoven’s, Bettina von Arnim, who said she was “one of the most unendurable persons” she had ever met. “With what pretension she seats herself at the piano and plays without the notes!” But plenty of others only noticed her talent, including the writer Franz Grillparzer, who penned the oration for Beethoven’s funeral and referred to Clara as that “innocent child who unlocked the casket in which Beethoven buried his mighty heart”.

It’s hard, in retrospect, to think of Clara as being quite as innocent as commentators at the time – nearly always men – liked to believe. Her upbringing in Leipzig was financially comfortable, but tough. Her mother, Marianne Wieck (née Tromlitz) – a well-known singer – had an affair with a friend of her father’s and the couple divorced when Clara was five. She was left with her father, Friedrich – an unrelenting man who no doubt drove his wife to leave him – and it’s possible that his ferocious command over his household is the reason why it’s been recorded that Clara was mute until the age of four, and possibly also deaf.

Friedrich was a pianist of the old school, owner of a piano shop, a critic, and a teacher. He was arrogant and overpowering, and with his daughter he saw a chance to create a child prodigy. On the one hand, he thought there was nothing wrong with a woman musician having a professional career (unlike Abraham Mendelssohn, who encouraged his son Felix, but stamped on the fortunes of his equally talented big sister, Fanny), but his control over Clara when she was young was suffocating and creepy. All the early entries in her diary were written by Friedrich, and he never allowed her to read. By hook or crook, she would become a great German musician, and his masterplan paid off. Clara was his best student. By eight, she was playing concertos by Mozart; by 10, she was touring Germany; by 13, she had begun work on her own piano concerto; by 16, it had received a premiere in Leipzig, conducted by Felix Mendelssohn with Clara as soloist. But there was a cost. “I am a girl within my own armour,” she tellingly wrote of her teenage self, and by the time she was 20 she was experiencing blackouts on stage, chest pains and other physiological and psychological illness.

Clara’s Piano Concerto still gets performed today. Designed to show off virtuosity, it’s full of drama, youthful energy and interesting details, beginning in one key, changing in the second movement, then flipping back. “If the name of the female composer were not on the title one would never think it were written by a woman,” managed one typically obnoxious critic; another inexplicably thought the key changes were suggestive of female deviousness. And it was comments like that, Anna Beer writes, which “help explain Clara Wieck’s recurrent anxiety about the value of her own compositions”.

Robert Schumann bowled into the Wieck household when Clara was 8 and he was 18. One of Friedrich’s students, he took a brotherly interest in Clara when she was young, encouraging her to compose, and became interested in her romantically when she was in her mid-teens. By the time they first kissed, when she was 16 (“I thought I would faint,” she wrote), he had already contracted the syphilis that would eventually destroy his body and mind (it’s presumed that the infection laid dormant until his later years) and been engaged to another woman. But these two details have barely got in the way of what the Cambridge Companion To Schumann calls the “most feted romantic love story in the history of Western music”, which comes complete with its own Hollywood film, 1947’s Song Of Love, starring Katherine Hepburn and Paul Henreid.

That Friedrich opposed his daughter’s eventual marriage on the day before she turned 21, and went to court to try and prevent it, is hardly a surprise. Robert was an unorganised and impractical man, a drinker and a gambler, who had made little progress as a composer by the time he walked Clara, already a seasoned professional, down the aisle (he was better known as a critic). She loved him deeply, they clearly had a very vigorous sex life, but she was nonetheless exasperated by him living “in the realm of the imagination”, as he said of himself. “Listen, Robert,” she wrote to him in the early days of their marriage, “would you compose something brilliant, easy to understand, something that has no titles, but it is a complete continuing piece, not too long and not too short? I would like so much to have something of yours to play at concerts that is suited to a general audience. It’s humiliating for a genius, of course, but expedience demands it.”

The mention of “no titles” is a reference to Robert’s propensity for writing freewheeling pieces called things like Davidsbündlertänze, Arabeske and Carnaval, rather than more typical sonatas and what-have-you (although he did go on to write symphonies, concertos, string quartets and other pieces in established forms). “As if all mental pictures must be shaped to fit one or two forms!” he barked, decades ahead of his time, and it’s been posited that Robert’s proto-avant garde attitude might have thrown Clara off the scent of her own burgeoning career as a more traditional composer of concertos, romances, and polonaises that could be played at her recitals, published and sold. “I have a strange fear of showing you a composition of mine; I am always ashamed,” Clara wrote to Robert and she certainly found it harder to compose after she married – for practical reasons (motherhood, him hogging the piano), and she might also have felt musically betrayed by her husband, who always spoke of forming a creative union with his wife. “You complete me as a composer, just as I do you,” he said. “Each of your ideas comes from my soul, just as I owe of my music to you.” In reality, her ambitions to compose took second fiddle to his, and, ultimately, her confidence was smashed: “I once believed I had creative talent, but I have given up this idea; a woman must not wish to compose – there was never one to do it,” she wrote in 1839. “Am I intended to be one? It would be arrogant to believe that.”

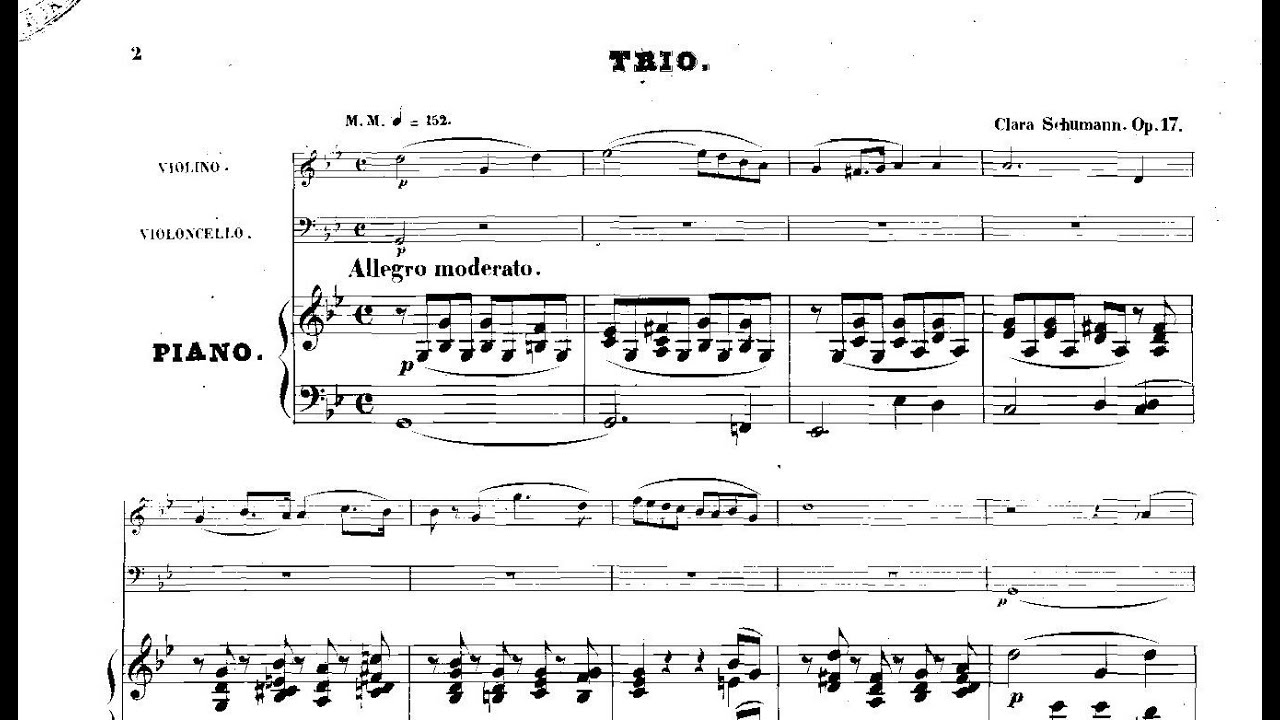

And yet, Clara Schumann did have creative talent – oodles of it – and she did deliver on the promise of her Piano Concerto with, particularly, her Piano Trio from 1846, which clocks in at around 30 minutes and makes up this A-side of this record, and her shorter piano works, including her Variations On A Theme By Robert Schumann (1854) and Preludes And Fugues (1845), which are on the B-side. All of those pieces were written after she said she had “given up”, but before Robert died, after which she quit composing completely.

Clara’s Piano Trio – described in the New Grove Dictionary Of Music as having “an autumnal, melancholy quality” and demonstrating “a mastery of sonata form and polyphonic techniques” – was written at a moment of turmoil in her life. Robert had had a mental breakdown in 1844, brought on, it’s thought, by him accompanying Clara on a relentless four-month tour, which including playing in Russia. (Clara survived the tour just fine and is recorded as playing five solo concerts in five days in Riga, with four different programmes.) The couple moved to from Leipzig to Dresden after Robert’s breakdown, with Clara heavily pregnant with their third child, Julie. Within a year of Julie’s birth, their first son was born (Emil, who died aged 16 months) and Clara also suffered a miscarriage on the island of Norderney, where the Schumanns spent the summer of 1846, because Robert’s health was barely improving in Dresden. It was in Norderney that Clara somehow managed to write her masterpiece, about which, in a rare moment of self-praise, she said: “There are some nice sections in the Trio, and I believe that its form is also rather well executed.” It was dedicated to Fanny Mendelssohn, who Clara believed was “undoubtedly the most distinguished [woman] musician of her time”. The two of them were becoming friends, but Fanny died suddenly in 1847 of a stroke, aged 41. Six months later her brother Felix, a supporter of Clara’s (she played “like a little devil” he said of her when she was young), was also claimed by a stroke, aged 38.

When a recording of Clara’s Piano Trio was released in America in 1952, the New York Times ran a review with the headline, “Clara Schumann: Wife of Robert was also a composer”, which tells us everything about how little her work was known until relatively recently. “He was the much stronger musical personality of the two,” the review said, but also, “We have been missing something by so consistently ignoring her music.” Since then, her music has been recorded and played with something approaching regularity and yet, as Anna Beer writes in Sounds And Sweet Airs, “the story of Clara Schumann, the composer, is far from a straightforward one. She may have been, as is claimed, a ‘creative partner’ to the men in her life, whether her father, husband or even Johannes Brahms, but these were creative partnerships in which some were more equal than others. Clara Schumann’s drive, determination and sheer energy were not, however, focussed on equality. She had other goals: she sustained her relationship with Robert Schumann, not only in defiance of her powerful father, but in defiance of Robert’s death; and she sustained her performing career, overcoming obstacles that would have blocked the path of a lesser woman. Powerful internal and external forces ensured that composition came a poor third to these great goals.”

Her instincts were always more personal than political, her obsession with making Robert’s music known her life’s fundamental goal. Was she also cheated by circumstance? She was honoured in her time, and continues to be today, but there could have been so much more of Clara Schumann’s own music, and that’s her tragedy as well as ours.