A man, fiftyish, walks into a record shop, accompanied by his daughter. While the young girl begins ravenously rifling through the bins, the man gazes around, slightly bemused. He approaches the clerk and begins telling a variation on a story the record store clerk has heard a hundred times: the man once owned thousands of LPs but liquidated them when he converted his collection to CDs. Unable to find anyone to take the crackly old LPs off his hands, he tossed the entire collection into a dumpster. "Boy, if I knew then what I know now!" he cries.

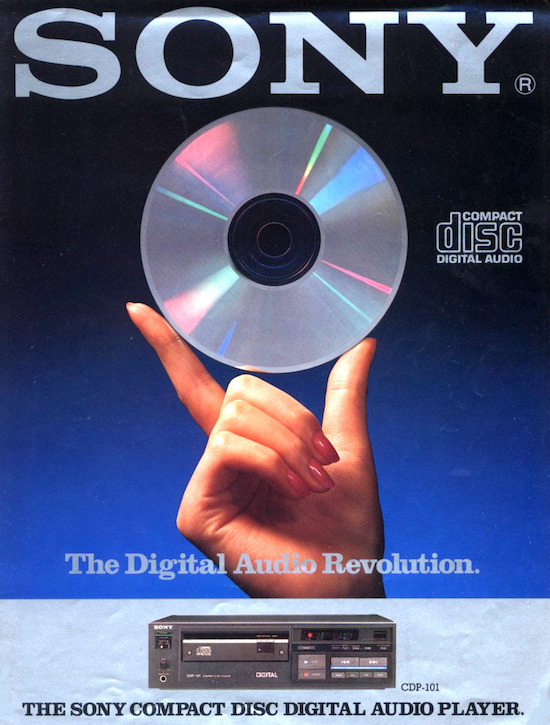

Indeed. In the early 80s, Sony and Phillips introduced the compact disc, a medium that promised the apex of crystalline sound, convenience, and veritable indestructability (or at least imperviousness to the rigors of the "breakfast time test"). Crucially, the CD was introduced not as vinyl’s alternative, but its executioner; early CD "longboxes" were even designed to fit into record store bins built to accommodate LPs, literally displacing them.

That was a long time ago. Now it is the CD that is being neglected, ridiculed, and jettisoned, as music streaming dominates the marketplace and vinyl enjoys something of a resurgence. Most new laptops no longer feature an optical drive with which to rip or burn the now-unfashionable CD. Since 2001, CD sales have dropped a startling 88%. US chain Best Buy recently announced that it will quit selling CDs; Target is likely to follow suit. In the UK, figures in January revealed that CD sales had dropped by a further 12%.Experts predict that by 2020 only a third of new cars being produced will come equipped with CD players, with most manufacturers phasing out the format as more drivers turn to music streaming services. But the decline of the CD feels sharp and sudden – and more than a little shocking to those of us who came of age as consumers alongside the rise of the format.

Much has been written about the relative merits and limitations of specific formats, and the discussions are as dull as they are complex. Zealots on either side of the CD / vinyl divide will breathlessly argue bit rates, dynamic range, and signal-to-noise ratio. I will not explore such minutiae here, as I do not intend to argue for the objective superiority of CDs over vinyl – or of any particular format over another, for that matter. My personal preference – all costs being equal – depends a lot on the kind of music I am listening to. An additional factor for me is price: when Neil Young, whose albums I have ritualistically purchased on their day of release since 1989, releases a new album on vinyl with a list price of $36.99 and a CD version for a quarter of that, because my primary interest is in Neil Young’s music and not in a specific format, and because I am not a Koch brother or even a Koch cousin, the decision is a no-brainer.

Your mileage may vary, and the truth is, the only arbiter lies in the ear of the beholder. There is no objective criteria or simple, one-size-fits-all consensus.

Yet the supposed obsolescence of the CD seems premature and suspiciously hasty. Does the format itself deserve its bad rap? The CD is still, to some of us, a thing worthy and precious enough to be stored in something called a ‘jewel case’.

The primary reason new technology replaces old technology is improvements in both convenience and quality: the new technology ostensibly renders the old obsolete. DVDs, like the clumsier Laserdiscs before them, offered far better quality sound and picture than the VHS and Betamax tapes they supplanted.

CDs, offering neither the more (some say) naturalistic sound quality of vinyl nor the convenience of streaming, would seem to offer little to entice a present-day music consumer. But let’s examine this.

Coexisting with Goliath: CDs vs streaming

Unlike other out-of-favour technologies, there is nothing inherently wrong with the way a CD functions; in fact, CDs still offer a more accurate representation of the music than that offered by most streaming services. Of the dominant streaming services, only relative underdog Tidal offers music in lossless CD quality. Spotify has been teasing a hi-resolution tier for years – going as far in March of 2017 as to create a short-lived beta version of something called Spotify Hi-Fi, presumably with the intent of determining price points – but as of yet, no such tier has been made available to subscribers.

It is in the best interest of corporations to accelerate the obsolescence of older technologies even as those technologies remain a viable alternative; what a company like Apple has to gain in hastening the demise of the CD is, I would think, fairly obvious. They’re counting on it not occurring to you that if you purchase a CD or record, you own it forever; if you’re willing to pay for monthly access to it, you’re paying for it forever.

I will concede that CDs win no points for style; aesthetically speaking, they are ghastly, especially when evaluated against the comparatively beautiful vinyl LP, or even the elegant and Korova Milk Bar-sleek iPhone. I recall helping an ex-girlfriend transfer her CD collection into convenient Case Logic binders and marveling at the pile of detritus left behind: the empty jewel cases, digipacks, and even box sets looked like nothing so much as a pile of plastic garbage. Even the discs themselves – which easily double, in a pinch, as both a compact makeup mirror and cocaine tray – subtly suggest the narcissism and excess we associate with the darkest aspects of 80s culture.

It’s true that for a certain type of listener, there are plenty of legitimate reasons to reject CDs in favor of streaming; it’s just that none of those reasons have anything whatsoever to do with the quality of the music on them, or their alleged inconvenience.

Ever Get The Feeling You’ve Been Cheated?: CDs vs vinyl

Unlike streaming, the vinyl record is inarguably less convenient than the CD and always has been, but its champions argue that the format’s true-analog sound is worth the trouble. Though I habitually collect vinyl and do agree that, for certain music, it is clearly a superior-sounding format, I harbor no romantic notions about the medium itself. I don’t find pops, hisses and crackles "part of the experience," but a thing that compromises the integrity of a great deal of the music I enjoy. Add to this the fact that much of today’s new vinyl is exorbitantly expensive, prone to issues of quality control due to overburdened pressing plants, and often digitally sourced – which means a new LP is basically a big, expensive CD with added vinyl noise – and, well, you could say I’m finding vinyl an increasingly tough sell.

It wasn’t long ago that the used rack at the record shop was overflowing with dirt-cheap copies of canonical albums by Pink Floyd, Led Zeppelin, Fleetwood Mac, and Jimi Hendrix. These same evergreen classics now routinely sell for upwards of $20 to $30 here in the US, and all that’s changed is the demand; there are still almost the same number of copies in the world. Boomers, seduced by the pristine sound of the new compact disc technology, once unloaded these records en masse, and the only reason they’re worth more now than they were twenty years ago is because customers are suddenly willing to pay premium prices for things that, not long ago, could be located in every third household in the United States.

Despite this, vinyl is – for the moment – quite collectable. CDs, on the other hand, are valueless to most, which means you can still find a "rare" CD almost anywhere.

There will always be those for whom the format remains as important – even more important – than the music itself, however. Once while working at a record store, I encountered a man in his twenties inquiring about an LP reissue of Hum’s 1995 album You’d Prefer an Astronaut. The album is one of those mostly forgotten 90s releases that has enjoyed an unlikely cult following among millennials and is desirable on vinyl. I pointed out that while the vinyl reissue he sought had already gone out of print, there were no fewer than three CD copies of You’d Prefer An Astronaut – and the band’s equally excellent follow-up, Downward Is Heavenward – in the used bin for about $3. Twentysomething wasn’t interested.

For all the talk of the internet leveling the playing field and helping to create a newly democratized music business, vinyl production – formerly the province of the budding punk bands and EDM producers who kept vinyl pressing plants in business during the CD-crazed 90s – is fast becoming the domain of the very wealthy and the very patient.

Here in the USA, to press 500 standard black LPs in printed sleeves can cost upwards of $3000; shop around a bit and you can produce the same number of CDs for less than a third of that price.

Most vinyl pressing plants estimate the turnaround for receiving finished LPs at around eight weeks (though in my experience as both an artist and label owner, it can take as many as eight months) and longer during busier times of the year; most CD duplication companies promise to have the same number of CDs on your doorstep inside of three weeks. To a young hardcore band embarking on their first tour, this differential can be crucial. One pressing plant I spoke with told me they’ve begun insisting on payment of balances in full – as opposed to the previous standard of requiring only a deposit – before they will cut a lacquer due to the increasing number of groups disbanding before receiving their records, leaving behind boxes of unclaimed, unwanted, and unpaid-for product.

Ironically, the format that Steve Albini once dismissed as "the rich man’s 8-track tape" might be the only alternative left for the working class artist or label who wishes to sell physical copies of their album online and at gigs. Getting fans in 2018 to actually buy a CD, of course, is another story.

A Preference for CDs? Surely You Jest!

There is a great deal of music for which CD is the superior format and for which vinyl is impractical: long-form drone music, blended DJ mixes, most classical pieces, and very quiet electro-acoustic compositions, to name just a few, all benefit from both the spatial and sonic advantages of the CD.

There also exists music that is compromised by the temporal limitations of a vinyl side. How do you determine where to place a side-break on Australian post-jazz trio The Necks’ seamless hour-long masterpiece Drive By, or on minimalist Eliane Radigue’s engulfing, brain chemistry-altering Trilogie De La Mort? What Deadhead can weather the buzzkill of having to flip a live Grateful Dead bootleg halfway through a ‘Dark Star’?

Then there are the tens of thousands of titles that have never been issued on any physical format but CD (some of which are unavailable even on Spotify). The majority of the extensive discographies of artists like Coil, John Zorn, and Matthew Shipp, for instance, has never been issued on vinyl. Ditto pretty much every jazz album released between, say, 1988 and 2002. And what about the numberless limited edition tour CDs and independently distributed CDRs? Entire "bonus" discs of exclusive alternate takes, outtakes, and b-sides? Is all of this music merely collateral damage, sacrificed on the altar of having instant access to almost everything? What gets erased, and what are the consequences?

CDs: The New Vinyl?

As rising prices threaten the so-called vinyl boom, we may begin to see the CD experience something of its own mini-resurgence. Recently, Pitchfork published two different pieces extolling the virtues of both the once-ubiquitous Case Logic CD binder and the Discman. Meanwhile, according to Discogs, CD sales are up, and a recent Buzzfeed piece claims that people in their 30s can’t stop hoarding CDs. What’s going on?

My friend Chaz Martenstein owns Bull City Records in Durham, NC. I asked him if he’s seen any recent trends toward increased CD sales. "I’ve definitely noticed a small interest in used CDs at the shop starting to rise again," he says. "It’s been enough to cause me to rethink my buying habits for the medium."

Martenstein attributes this spike to many millennials beginning to inherit their first cars: family hand-me-downs with dashboard CD players intact. He also cites the increasing scarcity of certain CD titles as a potential lure for older collectors. "There was a long period where a lot of us told hopeful sellers that no one was really buying CDs anymore, which probably led to a good amount being tossed out or destroyed," he says. "As the pool of available copies of one title shrinks, the more people want it."

While Martenstein admits that his customers still prefer vinyl by "about 90%," on the day I spoke to him, one of his regulars had just purchased "a stack of 24 used CDs."

It took a road trip with his Case Logic binder to reaffirm for Pitchfork writer Grayson Currin

"the supremacy of the compact disc when it comes to deep, dedicated listening." "CDs," he argues, "[give] you the mobility and clarity of a digital file while giving you an object to grasp, to study, to treasure." In other words, a CD represents the best of both worlds. Not a bad deal for something that, on the current secondhand market, costs less than a scone.

Veteran record collectors are also catching on. My friend Jeffrey Lewis is a renowned illustrator, author, and songwriter, and a life-long record fiend. He recently debuted a new song called "The Disease." The song deals with the familiar rite of passage of discovering records or, as he puts it, contracting the "disease for LPs." Then, for the final chorus, a very Jeffrey Lewis-y twist:

But nowadays it’s mostly CDs

No one wants to keep ‘em so there’s plen-ty

Folk and punk and private press and rap and indie!

Bonus tracks and liner notes or just emp-ty

As long as I can still make a good discovery

I’ve still got the music hunger disease

Crate-diggers like Jeff are realizing that the passion for collecting physical media doesn’t have to end just because it’s no longer fun, in a world of Pawn Stars and Storage Wars, to compete with flippers, prospectors and speculators for whom vintage vinyl is merely the latest exploitable fad. Good discoveries remain available for pennies on the dollar; you just need to open your mind to an unfashionable, unsexy format.

Will CDs ultimately enjoy the collectability of vinyl? Probably not. Despite the optimistic assurance printed in early CD booklets that the discs will "provide a lifetime of pure listening enjoyment," CDs have proven to be more ephemeral than initially suspected, prone to oxidization, ultraviolet light damage, and the dreaded disc rot.

Because of these and other factors, I by no means believe that CDs will ever become collectable; in fact, they are probably worth as much today as they will ever be. Like the VHS and 8-track tapes of yore, you can expect to find them choking the bins at charity shops until the end of time alongside Mills & Boon paperbacks, Breville toasters, and Primark cardigans. But while there would seem to be no reasonable argument for collecting CDs for their monetary value, collecting them for their intrinsic value – for the music contained on them – remains a worthy endeavor. It is my sincere belief that an instant collection of music will always be worth a trip to a Goodwill, a scour of a yard sale, or even a climb into a rubbish bin to rescue a neglected format from oblivion and give it a good home.

Just imagine if you had done that in 1988.