I’m a sucker for a cult figure in music, and in classical music there’s barely a more cultish proposition than Carlos Kleiber. He was one of the greatest musicians of the 20th century, but you can’t go onto Spotify and hear him play or sing anything, nor did he write music. He was a conductor, and, on the surface at least, a lackadaisical one. In a career spanning half a century, he conducted less than 100 concerts and about 500 opera performances (no one’s quite sure), and he hardly ever recorded. His Wikipedia page lists a hotchpotch of 20-odd albums of orchestral works, operas and live recordings, about half of which were cobbled together against his wishes, or released without his approval. “For me, okaying a recording is normally a horror,” began the only sleeve notes he ever wrote.

There’s a thriving online trade in Kleiber bootleg recordings and the list of his performances is forever becoming more complete, but they don’t change the essential fact – his was a pittance of an output compared to other conductors of his stature. And yet when 100 maestros were polled by BBC Music Magazine in 2011, he came out on top. According to his peers in the 21st century, and many others besides, Carlos Kleiber – dead at 74 in 2004 – was the greatest conductor who ever lived.

He could have done a lot more. From the 1960s onwards, he was hot property, constantly in demand as a freelancer, capable of commanding enormous fees, and he was never short of offers for more permanent work. In 1959, he turned down a deal with Decca Records – the most progressive label in classical music at the time – and didn’t record for another 14 years, tragically leaving a vacuum in place of what could have become a run of classic albums to match those he did eventually release on the Deutsche Grammophon label in the 1970s. And although he had a reputation for being unpredictable to work with and capable of vanishing into thin air in the middle of a run of performances, in 1989 he was offered perhaps the highest-profile gig in classical music – to replace the monumental figure of Herbert von Karajan as the music director of the Berlin Philharmonic, the world’s most famous orchestra. He said no, and all but retired from concert life shortly afterwards. (Kleiber once told von Karajan that he only worked when his deep-freeze was nearing empty, which was a joke, but he did once agree to give a concert for Audi workers near his Munich home in exchange for an Audi A8 with all the trimmings, presumably because his then-current car had broken down.)

Why was he like that? Why, if you’re born with such an extraordinary talent for music, would you not share more of what you’re capable of giving? There are some things we do know – that he was ultra-sensitive, childlike, crippled by self-doubt and prone to making demands on concert promoters that were impeccably unrealistic – but there’s also much that remains unknown. It was thought that he never gave an interview (one has subsequently turned up online – a radio interview, in German, from 1960) and he only once allowed his legendarily long and tense rehearsals to be filmed (see below, although there’s meant to be another film out there somewhere). Recently, some of his eccentric, charming and very funny letters have been published (in a fascinating 2011 book, Corresponding With Carlos, by the conductor Charles Barber), but without much non-musical source material to work with biographers and music fans alike have been forced to speculate wildly about his personality, pouring kerosene onto his myth.

In Kleiber’s story, the overpowering and complex figure of his father Erich – also a highly respected conductor – certainly looms large and there are eerie similarities between the works both excelled in, as if Carlos was driven to outdo his father’s legacy (he died in 1956). “The problem with Carlos,” a record producer told music writer Norman Lebrecht, “is that once Erich was dead, he saw the entire musical world as a surrogate. When he cancels a concert, he is killing his father, when he conducts a great performance, he is identifying with him.”

That sounds like cod-psychology to me, but it’s an intriguing thought and others have gone further in their amateur evaluations of Kleiber, suggesting that he may have been a manic depressive or even something of a mystic. In a 2012 documentary, Traces To Nowhere (also the title of the second episode of the first series of Twin Peaks, Lynch fans), it’s revealed by his sister Veronika that Kleiber’s “bedside book” was the Zhuangzi, an ancient text written by Chinese philosopher Zhuang Zhou. He was particularly consumed by one phrase: “Leave no trace,” or, to quote the line in full, “The Perfect man leaves no traces of his conduct.” In the same film, German mezzo-soprano Brigitte Fassbaender says he gave her a book, probably written by an Indian guru (he’d intentionally ripped off the cover), throughout which he’d underlined many passages, including: “We all know the fearsome emptiness lurking behind the way we live. Convictions give life the content we desire. Work becomes an indispensable drug. For its sake we accept all the depravations and disadvantages, and every illusion is welcome.”

There’s lot to chew on in both of those quotes, especially the former – just being, if you will, and not leaving anything behind seems an increasingly seductive outsider philosophy in an age of overwhelming information – but perhaps the biggest clues to Kleiber lie in the simplest facts of his biography. He was born in Berlin in 1930 to an Austrian father and American mother, Ruth, moved to Argentina aged five, as his family escaped the Nazis (he changed his name from Karl to Carlos while there), made his name in Potsdam, Stuttgart and Munich after the war, became an Austrian citizen later in life (for reasons of practicality rather than nationalism), and died in Slovenia, where his wife Stanislava – a ballet dancer – was from.

Much like Stravinsky, who I wrote about in the last of these columns, there’s something of the international man of mystery about Kleiber. English was his first language, but he also spoke immaculate German and Spanish, and he was well-read in the literature of all three languages. His sister believes his fragile, self-critical character derived from the fact that they moved around so much when he was young, rather than from having an over-powering dad, and that seems perfectly likely. His experience of different cultures unquestionably influenced his music-making, and in his mastery of an orchestra you can hear both Germanic precision and Latin flamboyance. It’s an intoxicating combination.

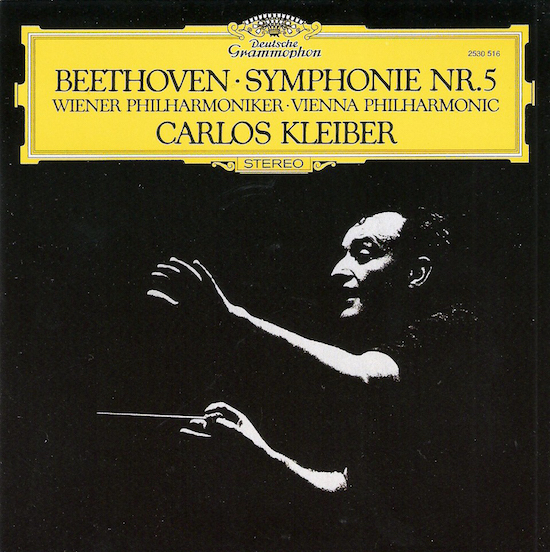

Kleiber devoted the bulk of his career to opera, especially in his early days, but he’s just as celebrated for his orchestral performances and albums – particularly his take on three Beethoven symphonies (the Fourth, Fifth and Seventh), Schubert’s Symphony No. 3 and Unfinished Symphony, and Brahms’s Symphony No. 4. New Yorker critic Alex Ross called his 1980 recording of the Brahms “one of the most potent symphonic recordings ever made”, and to people who know a lot more about classical music than I do the album I’ve picked for this column – Kleiber and the Vienna Philharmonic’s blistering 1975 charge through Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony is the greatest ever. “There truly does not exist a more thrillingly wondrous performance of this Beethoven double (and trust me, I’ve listened to a lot of them),” wrote Radio 3’s Clemency Burton-Hill about a twofer CD that also includes the Seventh Symphony. “I’m not alone: the consensus view is that these really are ‘definitive’.”

It’s the multitude of decisions conductors make – tiny and large – that define their art, and the ability to communicate with an orchestra on a transcendental level, before a performance or recording, and during. Kleiber prepared savagely ahead of a project (“When he was working on something, it was like a birth every time,” his sister says in Traces To Nowhere), ensuring that by the time he started rehearsals, as the Spanish tenor Plácido Domingo once said, “He has assimilated the score to such a degree that he can read through the notes to uncover all the drama and feeling of the music, everything the composer imagined. It seems so natural and simple, yet with all the preparation it sounds spontaneous.”

He was known for specialising in relatively few works, but privately he obsessed over the entire repertoire, and because he was also so well-read in literature, he explained himself to orchestras in a poetic manner that became storied – often using clean, simple phrases to convey his intentions (asking musicians to “play with nicotine” or to make their instruments “wink”), and occasionally by being more verbose. “Do you believe in ghosts?” he asks in the below 1970 film of him almost pulling his hair out trying to get the stiffest of orchestras, the Stuttgart Radio Symphony Orchestra, to meet his demands. “Excellent! It’s important for the overture. For the duration of the overture, I want you to believe in ghosts, alright?” And there are other great explanations in that rehearsal footage, including, “You have to win that long note, you have to fight for it,” and, “Not just notes! Flesh and blood!”

Kleiber’s playing instructions could be unorthodox, too. In a 2009 Radio 3 documentary, Who Was Carlos Kleiber?, the one-time director of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Peter Jonas, described how he’d get his violinists to bow in different directions – some up, others down – to create a seamless, flowing feel to a piece of music. He sometimes ordered orchestras to not come in at the same time, but at any time while he lowered his baton – giving the sense of a piece of music stealing its way into existence. And he also looked outside of classical music for inspiration, noticing how Duke Ellington would conduct his band. He stole a trick off The Duke and used it to bring in Beethoven’s Coriolan Overture, telling Charles Barber in a letter that it made the start of the piece sound like driving a Rolls-Royce into a wall at 60mph.

And then there was his aesthetic style on the podium – so different to his father’s. Erich Kleiber was undeniably a giant of classical music (some critics argue that he had the bigger career), but you wouldn’t necessarily spot his talents from watching him conduct. As Barber says, “Erich used a stick notable for its efficiency, clarity, and evidentiary purposes.” Conversely, “Carlos was an Aurora Borealis of light and transparency, all electric and surprising, and perfect in beauty… No one spoke more compellingly in every language of sound.”

We’d know much more about Kleiber’s relationship with his father if he’d spoken about it, but he very seldom did. Asked in the only interview that’s ever been unearthed whether Erich had encouraged him to become a conductor, he replies, “No, on the contrary, he opposed it somewhat,” and in that initial crackle of a disagreement over a choice of career (confirmed by Erich sending his son off to study chemistry in Switzerland), biographers have imagined a cataclysmic rift. Anybody who interacted with Carlos on a professional level was warned never to mention Erich, who was vain and capable of being brutally hubristic, and to top all of this off, there’s even a long-established rumour that Erich isn’t his father at all. Without a shred of evidence – just some cranks noticing facial similarities – it’s been suggested that Ruth Kleiber had received the baton of modernist composer Alban Berg, whose opera Wozzeck Erich had premiered in Berlin in 1925 (it later became a favourite of Carlos’s, too).

It wouldn’t be uncommon for the child of a famous and powerful man to struggle in his shadow, and it’s definitely tasty to think of Carlos forging a career-long war against the musical estate his father left him, constantly trying to better it. If he did, Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony was an obvious battlefield. In 1952, Erich recorded a taut and brilliant version with the Dutch Concertgebouw Orchesta for Decca – the same label that Carlos refused to sign to in 1959. According to music writer Norman Lebrecht, Carlos’s 1975 recording is a clear response, “filled with foreboding, rippling with an unnamed terror and manic wildness… He alternated in rehearsals between frustrated rage and personal concern, pushing players to their limits while cradling them with smiles and coffee-break conversation. By the end, they were prepared to give him their all. The result is a record that is universally revered, eclipsing the father, and unique to the prodigious son.”

That image of Carlos – ferocious, but also caring and gentle – sums up the contradictions in his character. He was famously reclusive, but he had a weakness for women (and fast cars, which helped him to get out of uncomfortable situations as quickly as possible). He had endless affairs throughout his long marriage, yet he adored his wife and died just seven months after her, distraught. Money never interested him, but he’d only work for astronomical sums, believing, as his sister said, that his fee was “a gauge of his own importance”. He never had a manager or agent, never signed contracts (until the job was done and it was time to get paid), and he despised any whiff of fame or celebrity – even the (public, at least) adoration of such huge figures as the American superstar conductor Leonard Bernstein. In his book, Charles Barber recounts a story of Bernstein slipping into a screening of a film of Kleiber conducting, bursting into tears because he was so moved, and exclaiming, “You’re a god, you’re a god!” to Kleiber’s intense embarrassment.

Not everything Kleiber did was universally praised. His propensity for walking away from projects with no warning, which became a kind of trademark of his later in life, pissed a lot of people off, and he did get some bad reviews, most memorably for a concert in London in the early-1980s that got up the noses of Britain’s notoriously stuffy reviewers (it was recorded for the BBC, but Kleiber demanded the tapes be destroyed). And there’s a real oddity in his catalogue of official albums, too – a surprisingly not-very-good 1976 recording of Dvořák’s Piano Concerto that featured the genius Russian pianist Sviatoslav Richter as soloist. It just doesn’t work, perhaps because Kleiber and Richter were kindred spirits – delicate, respectful beings.

They became friends, and Richter attended Kleiber’s last-ever performance at the Bayreuth Festival in Germany a year later. “I fear that as long as I live I shall never hear another Tristan [And Isolde, the Wagner opera] like this one,” he later said. “This was the real thing. Carlos Kleiber brought the music to a boiling point, and kept it there throughout the whole evening, unleashing an interminable ovation at the end. There’s no doubt he’s the greatest conductor of our day.” Richter went to find him backstage afterwards. “He seemed rather depressed and displeased with himself. I told him what I thought and he suddenly leapt into the air with joy, like a child. ‘Also wirklich gut?’ he asked. (‘So it was really good?’). Such a titan, and so unsure of himself.”