Bearing in mind that "we" never quite means "you and me" – what do we know about Pink Floyd?

That at first they were fierce: Syd Barrett’s trembling talent, a lifetime of wonder crushed into eighteen overlit months. Then, later, it was all The Wall and those puddingy stadium extravaganzas, a parody of profundity and a crashing bore. That seems fair enough, even if – like me – you have a soft spot for glue-thick gunge like Animals, or are happy to drift in the scented spaces of Wish You Were Here. But somehow, the period between 1968 and 1973 (when Dark Side Of The Moon changed everything) seems almost to have vanished from view. Cited by the obsessive or the contrarian, more commonly it’s left to rot, in the twin shadows of Dark Side and their work with Barrett – it didn’t outsell Jesus, and it isn’t The Piper At The Gates Of Dawn.

Listening to the albums, you may well conclude that there was a dead zone, stretching from Syd’s enforced removal up to ‘Echoes’ in 1971. A Saucerful Of Secrets is Carnaby Street psych, charged with some genuine experimentalism but still, for the most part, a Barrett hangover. More is a pleasantly dreamy movie soundtrack, but really just mood music; the studio disc of Ummagumma, hailed at the time as a masterpiece, now seems a laughable indulgence, and sounds like it was performed in boxing gloves.1970’s Atom Heart Mother is art-rock at its gawky, parping worst. Only on Meddle do the Floyd come into focus: ‘Echoes’ is everything British prog should have been, gliding through uncanny atmospheres and gigantic grooves, unearthy lulls and crescendos. You’d think it came out of nowhere. The consensus is clear – this was Pink Floyd’s fallow period.

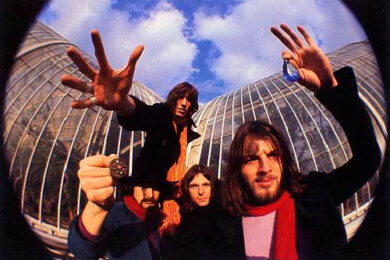

But as it turns out, on stage between ’68 and ’72 – right up to Dark Side, when the spontaneity was sucked from their act – they were something else. Pink Floyd in concert were almost unrecognisable from Pink Floyd on record: massive, crude and hypnotic, all power and effect. The live disc of Ummagumma hints at this, as does Pink Floyd Live At Pompeii, the atmospheric (and in the case of the in-studio interviews which punctuate the tracks, unwittingly hilarious) film from 1971, in which the Floyd freak out inside a ruined amphitheatre, and roam the foothills of Vesuvius with beards and satchels, like hippie hitchhikers wandered off course. But to experience the full weight of mid-period Floyd – and to dismantle preconceptions of the band as stuck-up, showboating dinosaurs (or at least, replace these with other objections) – you have to seek out those superior live shows, now available free of charge via the internet. Once a moneymaking scheme for unscrupulous non-music-fans, the ancient recordings are now passed around like joints, with strict orders not to make a profit, dusted and remastered by the Floyd "fan community" (which does contain – surprise! – its share of audiophile geeks). Listening to New Mown Grass, from San Diego in 1971, or Smoking Blues, from the 1970 Montreux Festival, Electric Factory from Philadelphia in the same year, or the roaring performance at the Paris Theatre for John Peel’s radio show in 1971, a different picture forms: Pink Floyd were for a time an astonishing, wildly exploratory rock band, ringing with forgotten promise.

Seven or eight songs, each lasting ten minutes or more. The set list barely changed for years. Appallingly complacent, of course – except that these "songs" were just vehicles for the Floyd’s chaotic, non-virtuoso improvisation, an edgy tumult far removed from a blues band’s formal jams, or the technical sterility of The Grateful Dead. The most durable numbers were the simplest to play, offering the widest scope for experimentation: ‘Set The Controls For The Heart Of The Sun’, a dense, repetitive mantra, which could be vague and ethereal or rumble up to peaks of punishing intensity, or the title track from A Saucerful Of Secrets, a sub-Stockhausen riot of battered cymbals and musique concrete (plus a juvenile finale of embarrassing choral pomp). Best of all, the show-stopping screamathon that was ‘Careful With That Axe, Eugene’, an extraordinary blend of minimalism and excess which scrapes chunks off the Floyd’s British contemporaries. Sometimes it sounds weightless and translucent, the tension understated; sometimes it’s unbearably oppressive, the shattering central section looming from the first note. Almost entirely improvisatory, ‘Axe’ is loosely but subtly structured, able to bear its own colossal weight – they almost never played it badly.

continues below

Pink Floyd – ‘Careful With That Axe, Eugene’, Live At Pompeii, 1971

From time to time, the Floyd would perform something more representative of their studio work – the potheaded frippery of ‘Alan’s Psychedelic Breakfast’, or Rick Wright’s ludicrous, plonking ‘Sysyphus’ – but they never stayed long in the set, because Pink Floyd live were all about sensation, and the cerebral scribble didn’t quite make it. They played the hell out of the rambling, progtastic ‘Atom Heart Mother’, but shorn of its aggravating orchestra and choir, it sounds like a different – and far better – piece of music. The ponderous grandiloquence might still raise a chuckle, but this stripped ‘Mother’ is a sequence of simple moments, swamped on record by Ron Geesin’s half-baked arrangement. Live, it sounds spacious and strong (though overlong), diversions through monk-rock and funkless funk notwithstanding.

These recordings highlight why Pink Floyd still have a right to be taken seriously, even as their peers are pariahs: the Floyd were at heart a rock ‘n’ roll band, stretching the form to its limit but never losing sight of its essential coarseness. For the most part British prog was, miserably and self-consciously, about music in the coldest sense: harmonic variation, time signatures, technical virtuosity. Pink Floyd didn’t, and couldn’t, match this cold craftsmanship – rather poor musicians by the standards of the day, unconcerned in any case with vulgar displays of technique, they survived and flourished by playing to their strengths. No other band bar Can had a better grasp of atmosphere and dynamics; only Faust so strongly favoured the thrill of sound itself over all other aspects of the form. The Floyd never did fit with the Brit-prog mainstream – their true contemporaries were that raft of German bands (on whom they were a primary influence), not trying to dress up small-band music in classical regalia, but to split it down the seams and unfold it like a paper chain. Before their work got bogged down with bombast and bungled attempts at depth, Pink Floyd live were truly progressive, with a small ‘p’. Expansive and often excessive, but unashamed of what they really were – a garage band floating in deep space.

In the end, Roger Waters’ crime was not so much his ill-tempered arrogance, but an ever-growing sense of himself as a "composer" (which he most certainly was not). So lacking as a natural musician that he couldn’t tune his own bass, Waters was at heart something of a musical primitive. You can hear it in his earliest songs (‘Take Up Thy Stethoscope And Walk’, from ‘Piper, a three-note assault which understands melody only as clutter; ‘Set The Controls’, a twelve-bar blues with the blues removed), and onstage it’s obvious. When not grimacing through those hippo-foot basslines, he’s making guttural noises with his mouth, battering hell out of a giant gong, clacking his bass strings off the pickup, shrieking into an echo box – anything other than being musical. It’s not so much ART as an attempt to infuse the Floyd’s drifting drama with some energy and aggression, a certain hardness of approach. Ringed with ornate noodling (Gilmour’s guitar sublimating the blues to vapour, Rick Wright’s haunted keyboard), the rhythm section is what keeps this music from floating, like smoke, into pure and meaningless indulgence. Replace Waters and Nick Mason with any bassist and drummer from the prog-rock pool, and Pink Floyd would be unbearable – at best, a frilly period piece. It’s Waters’ relentless brutalism and Mason’s ham-fisted, lolloping drums which root the Floyd (if distantly) in the music of Bo Diddley or Link Wray, roots which most Brit-prog did not so much transcend as shrink from, strangely ashamed. As though they knew better.

In the wake of _Dark Side’_s shattering success, Waters planned a follow-up called Household Objects, an anti-classicist pipe dream which would contain no musical instruments at all. The Floyd spent several months clinking glasses, ripping paper and twanging rubber bands before conceding this was never going to fly. Instead, they resorted to another LP of slow four-four tempos, misty keyboards and keening guitar solos; it was OK, but it killed them. Superstardom’s a funny thing – often it humbles those who were most hungry for it, while private, thoughtful types become monstrous. A semi-committed Communist, Waters’ initial response to success had been to move into a terraced house off Islington’s unlovely Essex Road, and give away as much money as he could. Now he was collecting Impressionist paintings, and drawing up tour contracts to ensure each five-star hotel was within easy reach of a golf course. The change ran parallel with Pink Floyd’s move into the mainstream, and the creeping arrival of a deep misanthropy. Out went his mordant wit, out went all sense of his own limitations. Waters became Pink Floyd’s haughty auteur, and the band were dragged behind, hitched to the caboose of rock’s most preposterous ego.

Like a lot of superstars, they turned to shit on stage. The first performances of Dark Side Of The Moon (at The Rainbow in 1972) sound uncommonly fresh, a band tackling a full set of new material for the first time in six years – we’re even spared ‘The Great Gig In The Sky’, its place still filled by a demonic tape collage of muttering vicars. By the time the album was out, the novelty had worn off, and playing the same songs every night with no room for improvisation, Pink Floyd became sloppy as hell. Pyrotechnics and ear-kicking volume were now used as misdirection; sludged-up with backing singers and hold-music saxophone (smeared over ‘Echoes’, in an act of outright vandalism), it’s possible to tell these shows apart only by their relative weariness. A new song from 1974 personifies the malaise: ‘Raving And Drooling’ is a juddering, bass-heavy squall which seems to observe the skinhead cult from a cautious but curious distance ("How does it feel to be empty and angry and spaced? / Split up the middle between the illusion of safety in numbers and a fist in your face") even as its blustering, megawatt riffs propel the band still further into private and privileged space. When it finally appeared, bloated and retitled, on 1977’s Animals, it spoke volumes – about how artistically constipated Pink Floyd had become, but also how muddled and muddy their aesthetic had grown: the lyrics had been rewritten as a tortuous social allegory about sheep.

continues below

Pink Floyd – ‘Mortality Sequence’, live at The Rainbow, 1972

The freedoms the Floyd had once allowed themselves were, at the time, a sign of resistance rather than complacency. Too smart (and far too middle-class) to chant revolution as a matter of course, the Floyd were a part of what was still called the counterculture, whether they liked it or not. Rather like those other well-spoken semi-rebels, Monty Python (whose Holy Grail was part-funded with profits from Dark Side), Pink Floyd were not overtly political in their work, and were in many ways extremely conventional people – yet they were all about flight from convention, buoyed on that wave of radical thought still moving through the West. With comfort came the rejection of chaos and spontaneity, and a slump back into some Victorian ideal of ‘the artist’. The newly-condescending Floyd, with their songs of pity for a failed society – well-rehearsed and utterly distant – were, in their dozy way, pure spectacle. For all their universalism, these albums about alienation are themselves oddly alienating. Out went the sense of adventure, displaced by ennui and glassy melancholia; the bleak, ghostly Wish You Were Here may be intermittently sublime, but reeks of defeat. The band’s new live show was a note-for-note recital of the album, followed by an equally rigid reading of Dark Side. Performing ‘Money’ for the four hundred and fiftieth time, in front of a film of weary commuters and sickly-grinning jet-setters, Pink Floyd were not unaware of the irony, but had lost the will (or the wherewithal) to change.

The 1977 tour to promote Animals (the ugliest-sounding platinum record ever) was more entertaining, if for non-musical reasons. Waters, by now sunk deep into millionaire’s gloom, is perpetually pissed – in at least one sense – and keeps lambasting the audience for their restlessness. "Stop letting off fireworks and shouting and screaming! I’m trying to sing a song!" It’s perhaps understandable that artists grown so very self-conscious might bristle at a crowd more interested in low explosives – but listening to the ground-in cynicism in Waters’ voice, it’s easy to imagine him screaming the same thing out of his bedroom window on Bonfire Night.

continues below

A collection of Roger Waters’ onstage tantrums, 1977

Famously, on the last night of the tour, he beckoned a fan to the front of the stage and spat in his face (though bearing in mind the reverence and docility of Floyd freaks by 1977, it’s possible that this fan never washed again – if, indeed, he had any plans to in the first place). The incident is ugly enough on its own terms, but it gets worse: a shame-faced Waters used it as inspiration for The Wall, an album so revolting on every level that it might be oddly compelling, were it possible to listen for more than ten minutes at a time. The Wall is the pinnacle of Waters’ conceit, not just for its unsparing inverted narcissism, but the lumbering grotesqueness of the music – like third-rate New Wave swollen to the size of a gas giant, a would-be symphony almost devoid of melodic invention. It spawned the least spontaneous live shows in history, choreographed and stage-managed, performed to a click-track to stay in sync with Gerald Scarfe’s hysterical cartoons. This is the Pink Floyd most people think of when you mention their name. It’s a terrible shame.

Those moments from 68-72, while never quite touching the beauty and invention of the Barrett years, are a universe away from this kind of clenched sterility. Unquestionably pompous and overindulgent, they can’t help but communicate a freedom (even a kind of optimism) which now seems… rather foreign. Too often, this band at this time are overlooked or undervalued, as an aimless whirl of pretention and exaggerated self-regard. Yet rather than nestling in the mouldy greatcoat of British prog, they fit into a post-psychedelic continuum that includes some of the strangest and most forward-thinking music of the age. Those crackly live recordings, sneaked out of town halls and sports arenas by the resourceful and the zonked, are their alternative history.