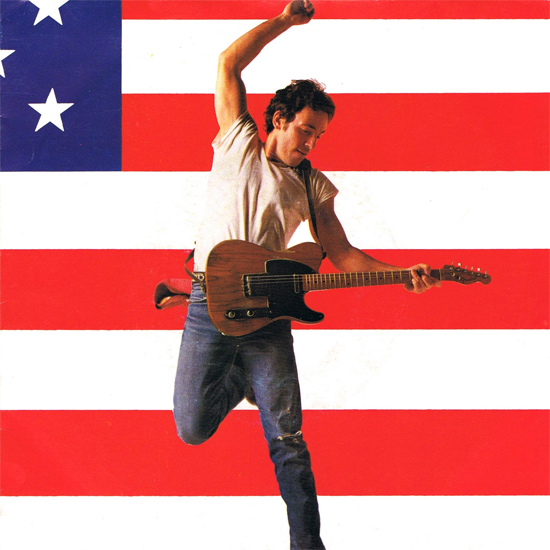

Sometimes you can tell just from a headline that you’re about to be made very, very angry. I dom’t know what possessed me to click through to an article entitled ‘Study suggests that listening to Bruce Springsteen could make you ‘racist” but I did, and now here we are.

Aside from the fact that the research in question, from the University of Minnesota, seems about as sociologically solid as a a cottage-cheese clipboard, its conclusions give malnourishing fodder to a lazy assumption that seems more and more prevalent. The equation of rockism, or just listening to mainstream rock, with racism is an extreme form of the common assumption in critical circles that rock music is ipso facto conservative in tendency.

The textbook anti-rockist article, Kelefa Sanneh’s Rap Against Rockism, asked: “Rockism isn’t unrelated to older, more familiar prejudices… could it really be a coincidence that rockist complaints often pit straight white men against the rest of the world?”. Many lesser critics than him have since picked up this idea and run with it, to the point that admitting a liking for the rock’n’roll canon essentially puts you on the side of the old and the oppressive.

Sanneh’s article, an elegant analysis of the way pop music has in the past been dismissed and belittled by old-school critics, made many valuable points. No doubt, there are many racist, sexist rock fans. There are also doubtless a lot of racist, sexist, hip-hop, dance and pop fans. There’s no need to look for something inherent in the nature of mainstream rock music that attracts or makes bigots because some idiots like it. The history of rock music, an older form than rap or dance, has historically been dominated by white men. But then, a lot of things have been historically dominated by white men. We’re getting there with that, you know, and there’s no need to throw the riffs out with the bathwater.

And yes, there are many closed-minded idiots preaching in the cause of rock who cling to false notions of authenticity. But, I’d argue, there are starting to be just as many annoying tits in the anti-rock camp who cling to an illusion of modernity. Pop or dance as the sound of the future, of youth, of shiny surface and Kylie driving her Kraftwerk-engineered car toward the neon boulevards made of synthpop, while Cro-Magnon guitar man screeches and smashes up his axe in frustration on the rocky hard-shoulder. There are critics wheeling out tired tropes on both sides of this false divide, and the most tired trope of all is the continued pitting of rock (whether you’re pro or anti) against other genres you perceive to be more progressive by their very nature.

As Sanneh also points out, the ideal here is not to defeat rock – it’s to get to a place where we don’t need to create such fake tribes. That’s not the way most of us listen to music. And it’s not like, if you actually look around you, rock is even a dominant form that needs to be overthrown any more. Example, Tinie Tempah, Ed Sheeran and Chase And Status rule the UK charts and live scene, and pop sales are on an equal footing with rock and on an upward trajectory. Far from disparaged from on high, pop is top of the critical pile, with guitar bands falling over themselves to identify themselves as pop fans and writers of pop music. Pop plays freely with rock’s regalia and poses, from Britney Spear’s ‘I Love Rock And Roll’ to the X-Factors omivorous cover pickings to Rihanna (and everyone else’s) declaration that “Ooh baby I’m a rock star” (This would be the same Rihanna, by-the-by, so beloved of poptimists, that just invited the man who beat her face bloody to guest on her new song. Progressive.)

In Jody Rosen’s equally excellent Slate article from 2006, The Perils Of Poptimism, he identifies himself as a pop lover, but says “Poptimism… is a pure product of the zeitgeist, and as such, it’s probably wise to keep an eye out for its perils, lest what began as a necessary corrective devolve into, as Sanneh wrote of rockism, a caricature used as a bludgeon against other music.” Rosen warned wisely against poptimism becoming a mere “glib exercise in pseudo-populism and in tweaking the boomers instead of a real effort to engage history and figure out what makes good music and why… Ideally, poptimism shouldn’t be about critics working through their daddy issues and straining to prove that they’re hipper than Greil Marcus,” he concluded. “It should be about openness to all kinds of music—including music that seems to embody rockist ideals… The rockist-poptimist polarity is often false, and even when it’s not, must we choose sides?”

It’s not a warning that many critics seem to be heeding. It’s become received form to have a sort of guilt about or scepticism towards bands who dared to consist of MEN playing GUITARS. The reformation of the Stone Roses was one recent bone of contention between rockist and poptimist camps, writers rushing to to their barricades. One of the greatest British guitar bands ever! Ladrock chancers! I wasn’t around so this means nothing to my flaming youth! Over in no-mans land, I wondered where I was supposed to stand if I was too young for them the first time round, liked Robyn but was actually quite excited because the Stone Roses wrote a lot of amazing songs? (I settled on ‘down the front, dancing’). You can automatically criticise, it seems, a band for being into the Roses, or Oasis, or the Jam, without needing further explanation as to why that indicates a stunted taste any more than if they cited Beefheart and Can or Aaliyah and J Dilla. Much as I’m not the biggest Vaccines fan, or the biggest Yuck fan, I do wonder what people are on about sometimes when the just as stylised and retro synthpop and industrial electronica of the likes of La Roux (who I love) or Zola Jesus (who I also love) get no such stick. They’re women, you see, with keyboards, so that means they’re from THE FUTURE. Are the likes of Client, with their haughty, I-am-a-sex-robot, Euro-froideur more modern because they wear PVC dresses and fetishise cold electronics rather than licks? Or are they pretty much Brother with a different, more critically acceptable set of references?

This assumption that electronic music is automatically more modern and progressive is an odd one. Guitars do not grow in clusters in Arcadian groves, dropping harmonics as they sway in the breeze. They too are meticulously designed machines in the strict sense of the word. That’s why the tuning pegs are also called machine heads. That’s why Woody Guthrie’s (yes, I’m going to talk about Woody fucking Guthrie, get over it) had a sticker on it that read ‘this machine kills fascists’. A guitar is no more natural or traditional than a Kaoss pad; the electric guitar and synthesiser were invented in the same decade, and yet guitar rock is routinely disparaged as stuck in the past.

And anyway, even if electronic music did have the future hardwired into it, the shock of the new that poptimists tend to crave is only one kind of shock, and the search for The New Sound can be a wild goose chase. As a younger form of criticism, when attempting to deconstruct pop and rock music, writers have often borrowed the tools or art and literary theory. Postmodernism of course, has much to do with the poptimist debunking of author-centred ‘authenticity’ and vaunting of commercial pop’s sparkly transience, its ironic revelling in itself as product. The bit of my my own undergraduate dabblings I always think of when I think about how songs work, though, is Russian Formalism (stay with me, the hamfisted academia bit doesn’t last long). That school of thought viewed literature as a series of devices, a machine for distorting everday language. By the way its form deviates from normal language, it focuses the reader’s attention both on the language and what it is saying. As Roman Jakobson put it, “organized violence committed on ordinary speech”. Similarly, the form’s deviation from itself, tiny tweaks of the unexpected in a familiar structure, can have a powerful effect. The form used and its antiquity aren’t really as important as how you choose to mess with it. Innovation within form is the source of artistic epiphany, not pure innovation, which of course, doesn’t exist. Similarly, the most hoary old blues can, by a sudden unexpected word or image, a blast of noise or a leftfield chord meander, slap you awake from its routine in a way that can be just as effective, if not more so, than scouring your ears in a bath of ‘progressive’ noise. In their survey of racist-makers, our friends in Minnesota also picked on Jack White, the man that more than any this past decade, has been a living example of that. Jack’s hero Billy Childish and his Stuckist friends also offer a useful counter to the notion that old methods can only produce tired content. You can still weave tomorrow’s trousers out of a frame loom.

But you shouldn’t have to go to such lengths to explain how brilliant ‘Let’s Shake Hands’ or ‘Atlantic City’ are. There shouldn’t be any shame involved in enjoying good mainstream rock music that walks the main road of blues and rock history; it’s not a guilty pleasure any more than chart pop is. To paraphrase Peaches on her witty guest spot on Chicks On Speed’s ‘We Don’t Play Guitars’, I listen to guitars, and love it. This does not make me a bad feminist, dim or limited, asinine or retrogressive in my taste. It most definitely does not make me a bit on the racist side. You can write open-minded, open-hearted music as well on a lute as you can an iPad. Or as the same Mr Bruce Springsteen put it in his wonderful, funny and firmly pro-pop SXSW keynote address: “The elements you’re using don’t matter. Purity of human expression and experience is not confined to guitars, to tubes, to turntables, to microchips. There is no right way, no pure way of doing it. There’s just doing it.” A good workman never blames his tools. And as Banarama once sang, it ain’t what you do, it’s the way that you do it. They didn’t play guitars either, but that wasn’t the point.