Johannes Brahms is a funny one in the history of classical music. When you first hear his work it seems older than it is, like he should be further to the left on the following timeline, by birth date, of the Big Guns of Broadly Germanic Music that I mentioned in a previous column on Schubert: Bach > Haydn > Mozart > Beethoven > Schubert > Mendelssohn > Schumann > Liszt > Wagner > Bruckner > Brahms > Mahler > Strauss > Schoenberg > Weill > Kraftwerk.

Yet he lived to see the birth of recorded sound and in 1889, eight years before his death aged 63, he was visited in Vienna by Theo Wangemann, a representative of the inventor of the phonograph, Thomas Edison.

Two deteriorated recordings of Brahms playing piano have survived and you can hear him introducing himself at the beginning of one. He sounds thrilled, and that messes with the stereotype of Brahms as something of a stick-in-the-mud, resistant to change.

History wants him to be an irate grandad struggling with the TV remote control but he had a far clearer sense of the future than many of his contemporaries and he loved technology. Before he played his two pieces for Wangemann, he heard a phonograph recording and said, “It’s as though one is living in a fairy tale!” and he was acutely aware of how other advancements in his lifetime – the rail network, the electric light bulb, the Steinway piano – had benefitted his life and career.

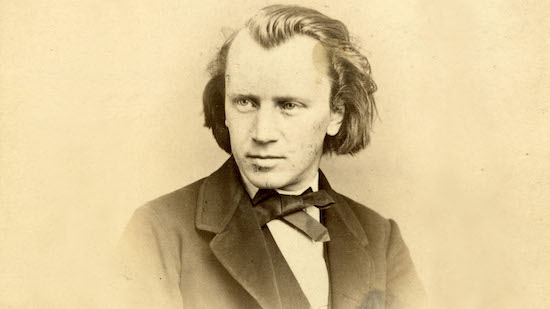

Brahms was a musical classicist who unashamedly looked back down the above timeline to the music of Schumann, Beethoven and Bach. In his time, he was pitched as an argument against the opulent futurism of Wagner, although he was the younger man by 20 years. “Everyone had to answer the question, ‘Brahmsianer oder Wagnerianer?’” writes Alex Ross in Listen To This. It was a culture war, but also a beef of sorts that Brahms deeply regretted participating in after he failed to land a punch that he’d thrown in 1860 when he was a dashing, clean-shaven upstart in his mid-20s.

With friends, including the violinist Joseph Joachim, he’d co-authored an attack on the so-called ‘New German School’, which included Liszt, the greatest pianist of his generation. A draft with just three signatures on it was leaked to the press and ridiculed, humiliating Brahms, who didn’t actually have much of a problem with Wagner’s music and later called himself “the best Wagnerian” because he studied his rival’s scores so intensely. His issue was more ideological – he thought the outright rejection of traditional forms was vain and arrogant, and resulted in “rank, miserable weeds growing from Liszt-like fantasias”.

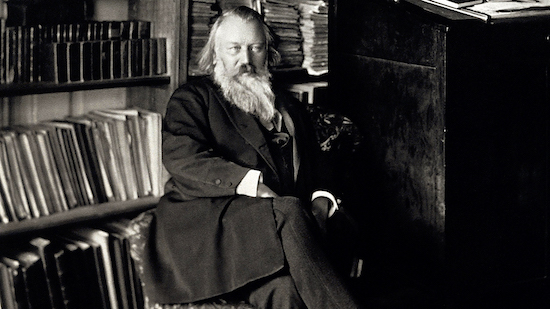

It’s possible that Brahms, an extreme perfectionist and intellectual of sound, thought of himself as a custodian of the grand traditions of Germanic music, or the last of a kind. The massive beard he grew in his mid-40s and his shabby clothing seemed to play up to that, like he was cultivating a wisened, professorial image. Apparently he even walked like Beethoven, bent forward with his arms clasped behind his back. Wagner, ever the megalomaniac, suggested his 1876 first symphony was essentially Beethoven’s 10th, and Mahler, also a progressive, had a pop too, once calling him “a puny little dwarf with a rather narrow chest”. It’s hard to imagine that Brahms would have minded. He knew and liked Mahler, and although he was capable of being very serious and a real grump, the abiding feeling about Brahms is that he was a soulful, generous man with a great sense of humour. “I am coming with a large beard!” he wrote to the conductor Bernhard Scholz. “Prepare your wife for a most awful sight.”

In the 20th century, Brahms was reappraised, most famously by arch-modernist Arnold Schoenberg, who in 1933 gave a talk crediting him with the advent of “unrestricted musical language”. And if it was Wagner’s intention to destroy all that he believed Brahms stood for musically, he failed. It’s too much to suggest that Schoenberg alone caused a new appreciation of his supposedly old-fashioned music after the Second World War (his talk, ‘Brahms The Progressive’, was updated in 1947 and published soon after), but it certainly got very popular again, and it remains so. Former New York Times critic Harold C. Schonberg wrote, “Brahms, in the 1960s, was elbowing Beethoven as the most popular of symphonic composers,” and it was noticeable at this year’s Proms that Brahms had five pieces performed to Wagner’s one. You could argue that Wagner is best-known as a writer of operas and the mainstays on the Proms’ programme are symphonies and concertos, but between the festival’s founding in 1895 and 1914 Wagner was by far the most-performed composer with 2,383 pieces to Beethoven’s 681 in second place and, way down the list, Brahms with 220.

“Cleary he had something very pertinent to say to future generations,” Schonberg added, and that’s absolutely the case with his magnificent German Requiem, a requiem for the living, not the dead, in which Brahms transposes lines from the Luther Bible to say: “You now have sadness, I will comfort you.” And that’s Brahms’s victory. We still look to his music because of its genius, but also because of the inherent decency of its message and the man who created it. Wagner was a rabid anti-Semite; conversely, Brahms exploded in rage when Karl Lueger of the Austrian Christian Social Party – a model for the Nazis – rose to power in Vienna at the end of Brahms’s life. “Anti-Semitism is insanity!” he said.

Brahms was never the kind of man to explain his work, but it seems certain that A German Requiem, written between 1865 and 1868 when Brahms was in his mid-30s, was largely inspired by the death of his mother in 1865. She was a seamstress, his father a jobbing musician, and early biographers suggested Brahms was raised in near-poverty in Hamburg, with his father having to perform in brothels to make ends meet. The claim was subsequently disputed as exaggeration; the Gängeviertel area of Hamburg, where he grew up, only became a slum long after Brahms had left, but he was certainly exposed to some aspects of the seamier side of life as a child, and they left a lasting impression – on his values, which were humane, and also his feelings towards women, which were nothing if not complex.

A German Requiem, which is a whopper at 70-odd minutes (Brahms’s longest composition), was written in stages, with the fifth of the seven movements being added after the official premiere. That movement includes the text, “As one whom he mother comforteth, so I will comfort you,” but it’s likely that the work was also influenced by the death of the composer Robert Schumann, his friend and hero, in 1856. Intriguingly, the extraordinary second movement – a funeral march and one of the most spine-tingling and powerful pieces of music Brahms ever wrote – uses material from an abandoned symphony that Brahms was writing when Schumann was dying. It’s like he’s weaving the memory of Schumann into the piece and he later admitted as much to Joseph Joachim, writing “how completely and inevitably such a work as the Requiem belonged to Schumann,” who Brahms later found out had coincidentally made plans to write a piece with the same name.

Brahms was 20 when he travelled to Düsseldorf to meet Schumann. It proved to be the most significant meeting of his early life, and not just because Schumann kick-started his professional career by writing a flattering article about him in a magazine he edited: “Hat’s off, gentleman, a genius!” When Brahms met Schumann he also met his wife, Clara, with whom he formed an intense relationship, especially after Schumann died. Just four months after he introduced Brahms to the music world in his magazine, Schumann tried to commit suicide by jumping off a bridge into the River Rhine and passed away two years later, aged 46, in an asylum, his madness caused – most likely – by contracting syphilis as a young man, which it’s assumed had remained latent for his married life. Clara, who was an exceptional pianist and composer in her own right, became a professional widow. It’s unlikely that she had a sexual relationship with Brahms, who never married, but, as Harold C. Schonberg writes, “They needed each other and they inspired each other. They also thought alike about music, had much the same ideals and aspirations, and were, intellectually and emotionally, much closer to each other than most husbands and wives.”

It’s thought that the opening of Brahms’s Piano Concerto No. 1, completed two years after Schumann died, is a musical depiction of his attempted suicide. That piece is now part of the standard repertoire, but it flopped at the time, buying Brahms time. A German Requiem became his breakthrough work. The ‘German’ in the title refers to the language of the text – it’s not in any way a nationalist piece (despite the second movement being bizarrely used as the theme tune for the BBC’s 1997 series The Nazis: A Warning From History) – and even calling it a ‘requiem’ is misleading. Not only are requiems traditionally sung in Latin, they’re associated with the Catholic Church and the fragments of text that Brahms used were taken from the Luther Bible, the key book of the Protestant Reformation. Also, Brahms, who was an agnostic, specifically avoids Christian dogma and mention of Christ, making A German Requiem feel non-liturgical and, as mentioned, it’s a requiem for the living – for those suffering grief – and not a mass for the dead. It’s non-judgemental in a literal and metaphoric sense, and it’s no surprise that Brahms later said he would gladly have called it A Human Requiem. There’s even a waltz in its fourth movement for those that fancy a dance, because, as the text in the fifth movement says: “Now you have sorrow, but your heart will rejoice again.”

“It is a truly tremendous piece of art which moves the entire being in a way little else does,” wrote Clara Schumann in a letter to Brahms. After the misfire of a partial premiere of its first three movements in Vienna in 1867 (the timpanist ballsed up and played ‘fortissimo’ in a quiet passage, drowning out the rest of the orchestra), it became a sensation and was played across the world in the years to come. Not everyone liked it. A performance by the New York Oratorio Society in March 1877, resulted in The New York Times saying, “It is exceedingly scholarly, but its length and monotonousness are such that it is scarcely likely to impress any but students,” which is a classic ‘don’t bore us, get to the chorus’ review and exactly the kind of thing Liam Gallagher might have come up with had he been around at the time. And Wagner, of course, hated it, believing it was bourgeois. “We will want no German Requiem to be played to our ashes,” he scoffed.

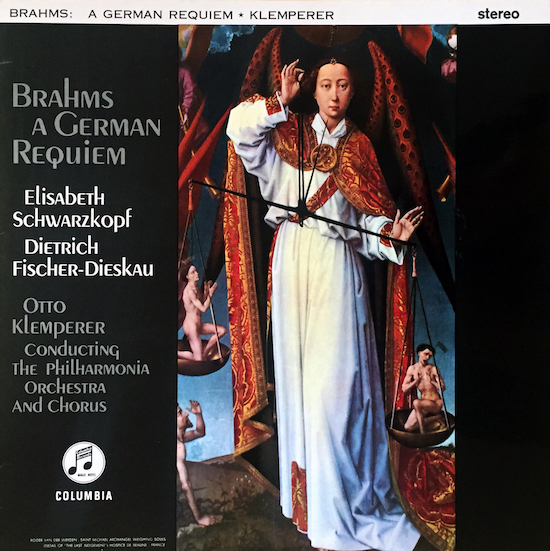

The recording I’ve chosen for this column is perhaps the most famous one – the uncompromising, German-born Otto Klemperer (above) conducting the Philharmonia Orchestra and Chorus for EMI’s Columbia Records in 1961. It’s heavy, thick, slow, and superb, and I also love it because it has such starry soloists – the soprano Elisabeth Schwarzkopf, who had caused a scandal by choosing seven of her own recordings (out of eight) when she was on Desert Island Discs three years previously, and Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, the heavy-smoking (at the time) baritone, who Schwarzkopf called “a born god who has it all”. Producing was Walter Legge, Schwarzkopf’s husband and a ruthless visionary in the history of the British classical music business. Legge got the crack Philharmonia Orchestra together specifically as a recording machine for EMI and he also had the foresight to sign the accident-prone Klemperer, who had a bad fall at Montreal airport in 1951, resulting in him having to conduct sitting down, and who later set himself on fire while smoking in bed. A left-wing Jew, he also survived the Nazis, who forced him to leave Germany for America in 1933, a brain tumour (the operation to remove it in 1939 left him partially paralysed) and periods of severe depression. With Legge at EMI in the 50s and 60s, he had a genuine Indian summer and we find him here at the peak of his late-career powers. He died in 1973, aged 88.

“He [Brahms] addresses us not in the godlike voice of Bach, nor in some Mozartian or Schubertian trance, but on roughly equal footing, as one troubled mind commiserating with another,” writes Alex Ross in Listen to This, and for all the intellectual rigour of Brahms’s music, it’s that deep-rooted universality that has helped it to not just survive, but thrive. Noticing that the 2016-17 New York concert season was more or less bookended by performances of A German Requiem, New York Times critic James R. Oestreich wrote in May that the piece “has become something of an anthem for our time, with grand social and political reverberations”. Brahms, you suspect, would love that, although it’s a highly personal piece without obvious political intent. He may have mined the past for inspiration, but he was also ultra-conscious of how he would be viewed in the future, long after his death. He destroyed works that he didn’t rate and tossed letters from Clara into the Rhine, hoping that the abstract, otherworldly compositional voice of the music he was proud of would talk for him in perpetuity. It does. He grows, just as Wagner is destined to slip away.