In Daphne du Maurier’s The Birds, first published in 1952, our feathered friends stop singing and start killing. In the short story, which inspired Alfred Hitchcock’s 1963 film of the same name, du Maurier depicts a vivid soundscape where the gulls and jackdaws have gone ominously quiet. At the height of the avian assault, farm worker Nat and his wife and children huddle around the wireless waiting for updates on the unfolding calamity, getting unnerved when the radio offers a blast of dance tunes in lieu of a news bulletin. In a tale dominated by birds, there are virtually no descriptions of their vocalisations. Set in a bleak winter on the Cornish coast, wings flap and beat en masse. Beaks tap, peck and hammer, but rarely chatter, chirp or sing. When Nat and family venture outside, they are met with a dread filled scene of birds silently staring at them. The main song in the story comes from a human, Nat singing to himself as he nervously tries to reinforce his house.

The bird’s attack goes hand-in-hand with climate disturbance. The weather is out of whack, the winter unusually brutal. Things seem “unnatural, queer” and Nat speculates it has something to do with the Arctic Circle. While there are references to the Blitz, likening the bird attacks to air raids, there’s also a sense that it’s describing the season’s going rogue.

When you read Du Maurier’s short story, birds seem inseparable from something deeper going awry. Their actions are a measure of whether everything’s in balance and the seasonal cycles are in sync. If they stop singing, and start pecking and flapping, things get terrifying. Her story brings home how significant the sounds birds make are for placing ourselves in the world, for understanding our environment and the moment. Those same themes come up when bird sounds enter human music, from quotations in classical compositions to peculiar chirping automatons.

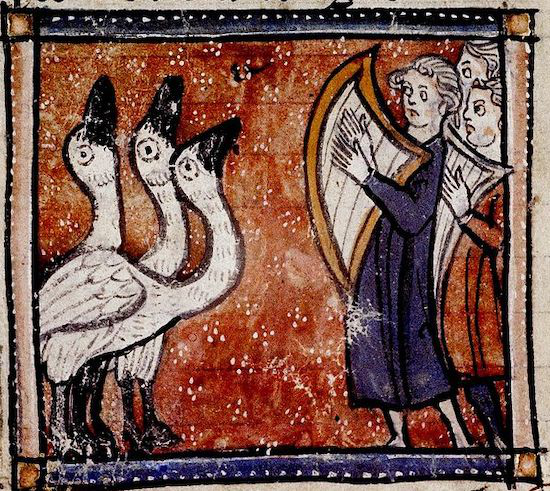

Just how tied bird song is to our understanding of the world can be brought home by turning to folkier traditions. Dating to the thirteenth century, ‘Sumer Is Icumen In’ is one of the oldest English songs documented. It has two sets of lyrics, in Latin and Middle English. The latter document the coming of summer (although there may also be a bawdier subtext around adultery). The song describes the sounds of animals as the seasons change, and whether it’s about a cuckhold or a cuckoo, it’s clear the song’s maddeningly catchy chorus mimics the song of the latter.

A bird song provides the material for the song’s evocation of summer’s arrival. But we can hear more when listening to birds than to calendrical analysis. Bird songs aren’t immutable. Research published in the US in 2010 detected a gradual increase in the frequencies of sparrow songs around urban areas over the course of thirty years, the birds starting to sing higher to be heard in noisier environments. Meanwhile, soundscaping is increasingly used to measure an ecosystem’s health. Birds are part of that – if you hear fewer birds singing, something’s going wrong. In other words, there’s a two-way process. Birds get put into human songs, but human actions are also affecting bird songs.

What we hear when we listen to birds tells us something about the birds, but also about ourselves and the world, and the same goes for how we record bird songs. Two new records, Synthetic Bird Music, a compilation from the Slovakia-based Mappa label, and the latest record from London-based sound artist Kate Carr, A Field Guide To Phantasmic Birds reinforce the point. Neither is purely a field recording collection (despite the title of Carr’s album referencing that tradition). They’re evocations, imitations, approximations. They mark the changing ways birds are documented and responded to, and the different messages humans pass on when working with avian communication.

Of course, the presence of bird song as a texture in electronic music is a much derided cliché, so how are these two releases different? Part of the answer is that the bird sounds used are anything but benign or tranquil. They aren’t scenery but lead actors. Carr’s album feels parallel to the ominous soundscape in du Maurier’s story. Where the latter evokes a world marked by the birds turning silent, Carr seems to ask what if we could find a space where all birds are equal and all can sing unencumbered. The avian sounds come from a selection of bird horns, as well as dawn chorus field recordings taken from South Africa, Australia and the UK. They’re played through arrangements that are more lunar than terrestrial. Stark yet euphonious textures encase bird vocalisations which go beyond generic chirps into a rich tableau of clicks and croaks.

Carr’s record evokes a hermetically sealed space for avian flourishing, as if these bird’s voices have been deposited in a safe haven where they can truly thrive. There’s a juxtaposition between the vibrancy of the bird sounds and mournful ascent of the electronics. A sadness imbues these four tracks, perhaps an awareness that the Field Guide she’s created can only ever be fictional. Carr’s album doesn’t strive for authenticity but, as the title suggests, an ideal.

Synthetic Bird Music is more jovial in tone, but it sits in a similarly fantastic register. From synthesizers to strings, percussion and, in Rie Nakajima’s case, a bag and a whistle, we hear artists mimicking the sounds of birds. What unfurls is a collection of strange rhythms and unexpected melodies. It shows that, if you really follow what the birds sing, you’re going land in some radical sounding music.

At a time when human actions and climate crisis have put 49% of bird species in decline, and one in eight under threat of extinction, context means both Carr’s album and the Mappa compilation can’t help but carry a melancholic edge. They have an urgency beyond mere curiosity. Where du Maurier shows how terrifying things get when the birds stop singing, Carr and the artists who’ve contributed to Synthetic Bird Music show how tragic it would be. Both records explore a perplexing range of bird vocalisations (and imitations). And this embracing of diversity is a powerful statement in itself when biodiversity is in decline.

But there’s more to these releases than a lament. The sheer variety of sounds suggests a distinct way of listening to nature. An acknowledgment of the complexity of the subject. A sense that there’s something more going on in birds’ brains than singing to each other. This becomes clearer by taking a longer look at some of the ways birds and human music have tangled together.

Avian inspiration on human music has deep historical roots far too broad and complex to fully cover here. Bird melodies have inspired composers for centuries. Bird calls are quoted in ornate orchestrations in the second movement of Handel’s ‘The Cuckoo And The Nightingale’. They influenced the flurries of violins in Vivaldi’s ‘Violin Concerto In A Major’.

Jump forward a few centuries, and two works from French composer Olivier Messiaen, Oiseaux exotiques and Catalogue d’Oiseaux go further. Messiaen was fascinated by birds, going to great lengths to catalogue and notate their songs. The former work focused on composing from birds found around France. The latter is more global, Messiaen notating the cries of 38 different birds, mostly from North America but also Asia. He included the full list of birds quoted in the score’s preface, while the song of each individual bird is also marked in the score. It’s a hopping, jaunty, bewilderingly dynamic piece, where the pianist gets twisted into all manner of unpredictable melodies and wind and percussion instruments bring in rich colour and movement.

With this history, why are the Mappa and Carr album’s so fascinating? To my ears, neither seems interested in squeezing bird songs into the constraints of human made compositions. They don’t gravitate to the obviously musical songs of cuckoos and nightingales. They’re closer to Messiaen than Handel and Vivaldi, but they still feel separate. They’re as much about maintaining a sense of otherness as they are about reconciling birds with human music.

It’s a nuance which gets at a subtle shift in the different ways birds are heard. In 1904, the artist F. Schuyler Mathews wrote Field Book Of Wild Bird And Their Music, Mathews’ book went deep into the bird songs of the Eastern United States. Part of his project was to transcribe bird songs to piano scores. Reading this book, you see Mathews getting overwhelmed with the complexity of his subject. “No! never does Nature repeat herself; it is not one vast mediocre chorus, it is an endless variety of soloists whose voices filled with tone-colour, redundant in melody, replete with expression, and strong in individuality, make up the orchestra which performs every year the glad spring symphony.”

However, as you read his attempts at the perilous game of trying to notate birdsongs, there’s a sense he’s only hearing birds through the lens of conventional human music. It’s an approach that both Carr’s album and Synthetic Bird Music feel distanced from, and that’s a pertinent distinction at a time of growing awareness about the complexity of bird communication and intelligence.

Irene Pepperberg, a US psychologist, spent years working with a grey parrot named Alex. She found that beyond mimicking words, Alex could identify certain objects, colours and even count. According to Pepperberg, the last words he said before dying were, “You be good. I love you.” It’s not just parrots, recent research found that Japanese great tits use compositional syntax, that is, they combine the ten different calls in their vocal repertoire to convey different meanings, in ways similar to how humans would make sentences.

In other words, the sense in du Maurier’s avian uprising that an ungraspable intelligence is governing birds has something behind it, but it should be a source of wonder rather than terror. It makes sense, then, that contemporary explorers of bird sound might look beyond what we can easily recognise as songs. This isn’t something limited to Carr’s album and Mappa’s compilation. Ute Wassermann is a German vocal improvisor whose sets are bewildering displays of extended vocal technique, her voice dialoguing with a series of weird and wonderful bird whistles. Her approach isn’t about finding the songs in the bird’s vocalisations. For this listener, Wassermann’s music is about embracing difference as much as familiarity between humans and birds. She might bridge the distance with her performances, but she doesn’t try to reduce it.

This gets at another history that Synthetic Bird Music and A Field Guide To Phantasmic Birds sit in, that of humans mimicking the sounds of birds through their own voice, or technology, but not necessarily trying to incorporate them into music. This goes deep into human history. Earlier this year in Israel, bones from tiny prehistoric birds with holes bored into them were identified as flutes. The theory is that they were used to assist with hunting, mimicking the sounds of birds of prey to startle smaller birds and make them easier to hunt.

But mimicking birds wasn’t just about ways to lure them to death or captivity. There’s been a trend, since the onset of industrialization at least, of people wanting to bring bird sounds into their homes. To hear their songs without having to, or perhaps being unable to, go out into the wild. In the nineteenth century, inventors such as Pierre Jaquet-Droz and Blaise Bontems built businesses developing and selling clock-work singing automatons. In the early years of the recording industry, it wasn’t possible or practical to make wildlife recordings. Instead, human imitators, virtuosic vocal artists capable of mimicking the sounds of wildlife, were brought into the studio. The most well-known descendent of this tradition, for a British audience at least, is perhaps Percy Edwards, but he was just one in a long, globe-spanning history of animal impersonators.

Synthetic Bird Music is as tied to this history as it is Handel and Vivaldi. It’s in how so many of these tracks sound artificial. They don’t disguise the fact they’re imitations but embrace it. Jonáš Gruska’s ‘Svitanie’, Vic Bang’s ‘Whizz’ and Ursula Sereghy’s ‘Kolibřík’ don’t hide the electricity and circuits behind their creation. On Ecka Mordecai and Malvern Brume’s ‘Pigeon Tones For Eggflute’, you can hear the human breath, and a passing car, underneath the coos and wooden warbles.

Audio recordings of wildlife have been made since the nineteenth century, and from Ludwig Koch’s recordings in the 1930s, recordings of birds and other wildlife have been commercially available. There’s a wealth of recordings available of a whole host of wildlife. Synthetic versions should surely be unnecessary if this is only about hearing authentic bird sounds, yet they persist. Why is that, and why does it matter?

This is not just a peculiarity of the Mappa compilation. A similar thread runs through Laura Cannell’s recorder-led reinterpretations of bird song on last year’s Antiphony Of The Trees. Significantly, they avoid questions about the ethics of wildlife field recording, and just how non-invasive you can be when you’re sticking microphones in front of unsuspecting animals. Synthesising the songs of birds is perhaps a fairer way of appreciating their complexity, and in a way, perhaps also a more direct way of highlighting difference and similarity to musician and listener alike. In Carr’s album meanwhile, we get artificial sounds dancing among real birds, seemingly recorded at a distance. A strange tableau which brings home just how fascinating, and how utterly unhuman our feathered friends truly are.

A Field Guide To Phantasmic Birds and Synthetic Bird Music point to different ways of hearing the natural world. They’re compositions which draw attention to the things we might not notice, the things that might get missed when we think about bird sounds. They encapsulate ways of hearing birds which embrace a richness beyond what neatly settles into our own ideas of musicality. They’re a celebration of complexity and what’s unknowable, the richness of terrestrial creatures which at points are capable of sounding utterly extra-terrestrial. A way of listening to birds that feels tethered to an awareness that their diversity is as fragile as it is brilliant.