Three Album Run is a series of tQ essays where we explore the best unbroken run of LPs in different genres. We’ve already looked at Krautrock but if you want to suggest a genre for a future essay please email John@theQuietus.com under the heading Three Album Run. The full rules are at the foot of this feature.

Once upon a time, during what was not so much a “golden age” as an ejaculatory age of denim and leather (and occasionally lace), there was no higher human aspiration than to “rock”.

Teenagers – a recently invented term for a class that had previously been a source of cheap farm labour, whose numbers were determined by luck, vermin, and a Papal workaround known as the rhythm method – were, all of a sudden, the judge, jury, and executioners of culture. For most of recorded history the earliest “gangs” or “crews” of these proto-persons were subsidised by their families, if only as a hedge against consumption and/or the Somme, but the combination of post-war prosperity and Frank Sinatra-induced horniness had resulted in a “boom” of these cretins. So they were given a name, allowed to keep whatever they earned at the malt shop, and set loose on the world. With this newly acknowledged population – simultaneously hated, pampered, used as both tastemaker and cannon fodder, plus altogether eroticised to an ooky degree – came “the 60s”. Which was exhausting, but was happily followed by the 1970s, where things got awesome. Because the 1970s was when the counterculture of the 1960s; the counterculture of the 1980s (which is given the arbitrary start date of 1977, but actually started a decade earlier); and a vague, deracinated misremembering of the 1950s all converged, like an episode of Dr. Who, but with tighter pants.

The result was an endless panoply of teen-dream marketed art, where volume was an inherent virtue, ass and grass were codified as commodities rather than communal properties, and rock songs were easily identifiable by both their surly attitude and their having “rock” in their titles. If, in the 50s and 60s, rocking and rolling was a metaphor for fucking, the teenagers of the 70s were comfortable saying “fuck”, so rocking became a metaphor for itself, with the transcendent state of rocking achieved via itself; a zen and tautological journey from rocking to rocking. This journey had many sherpas, and just as many frozen bodies left behind. It was, to coin a phrase, a long way to the top.

AC/DC started in 1973 as a quasi-family band. Two brothers, Angus and Malcolm Young, whose brother, George, served as both mentor, producer, and occasional bassist. George Young had already forged a successful music career, having written ‘Friday On My Mind’. But he’d failed to achieve the international success he craved and he’d seen his band, The Easybeats, fall apart because of compromise and a failure to rock. All three brothers set it in their minds to not repeat that mistake.

What followed was a rotating cast of bassists, and drummers, all prone to being let go at a (literal) moment’s notice. By the middle of the decade, the band was almost famous, an Australian rock band who were regionally popular in some of America’s greasiest secondary markets and who were being called “punk” by the UK press a year before the first Sex Pistols album came out. They were mainly known for their two frontmen; one a virtuoso guitarist who dressed like a school boy and played brutalist squalls of post-blues while spinning on his back like a centipede, and the other being Bon Scott, a singer with painted on pants, the voice of an asphyxiated Rod Stewart, and the face of a young Eugene Levy.

It’s generally agreed that AC/DC solidified with 1977’s Let There Be Rock. As if to bolster that future claim, the album’s title track is a propulsive, if chronologically iffy, recounting of rock & roll’s history, framed in the language of Genesis (the book, not the band). The same song also serves to illustrate how AC/DC was not quite at their peak, suffering as it does for making the uncharacteristically subtle mistake of having Bon Scott shout, “Let there be guitars!” and then allowing a full four seconds to elapse before the guitars kick in. (Three years later, on ‘Juke Box Hero’, Foreigner would not make the same mistake.) As the critic Mosi Reeves has pointed out, ‘Let There Be Rock’ was also an unfortunate example of a white band delineating an artificial line between heavy guitar music made by Black musicians and heavy guitar music made by white musicians, with the – unintentional – result being that AC/DC gave credence to rock radio’s thoroughly racist policy of designating the boogie-fied ruckus made by bands like AC/DC as more “rock” than, say, what Mandrill or Funkadelic was up to at the time.

Despite the continuing condescension thrown at their Aussie-ness, from 1978 to 1980, AC/DC were an Australian band consisting of a solitary Australian (though one so Australian that he was in Coloured Balls), one English journeyman, three Scots (one so much a True Scotsman that he took a not exactly truncated derivation of ‘Bonny Scott’ as his moniker) and – after said Bonny Scott met his not so bonny end – yet another Brit (one so British that he’d been in a band called Geordie and dressed like Andy Capp).

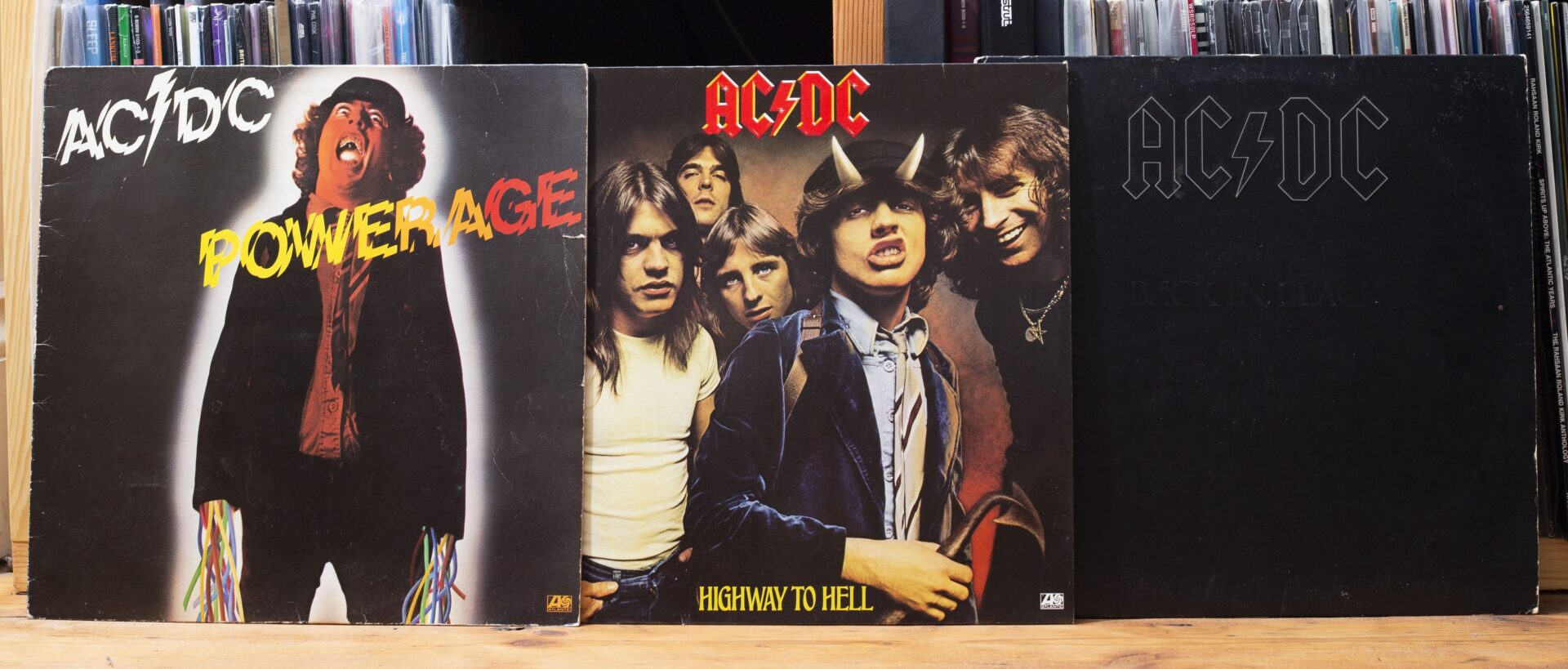

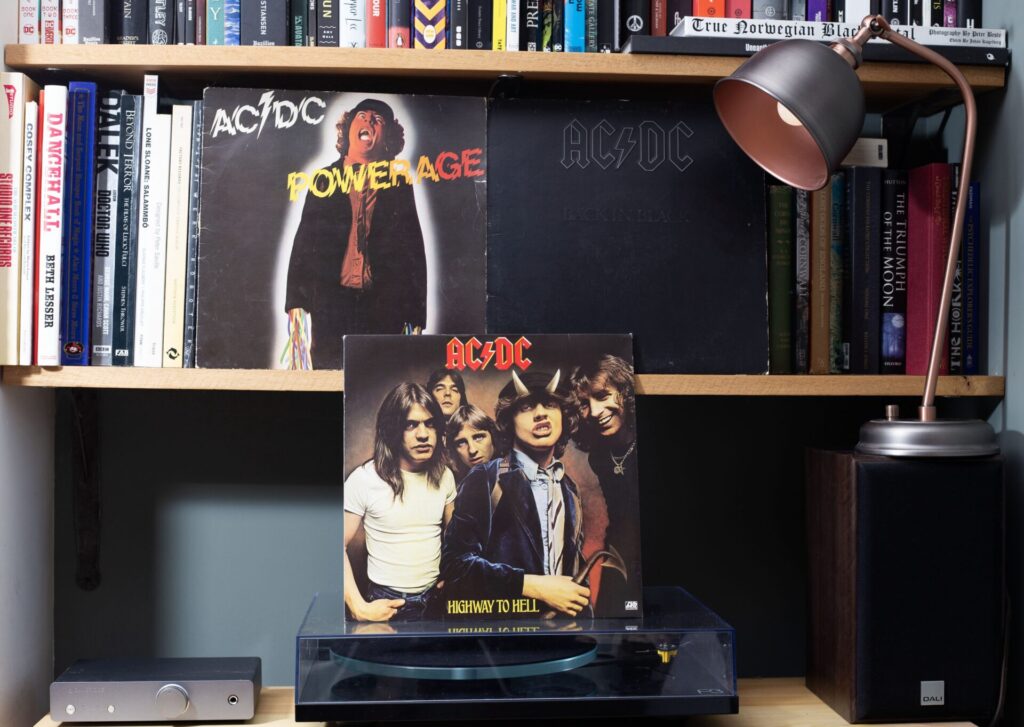

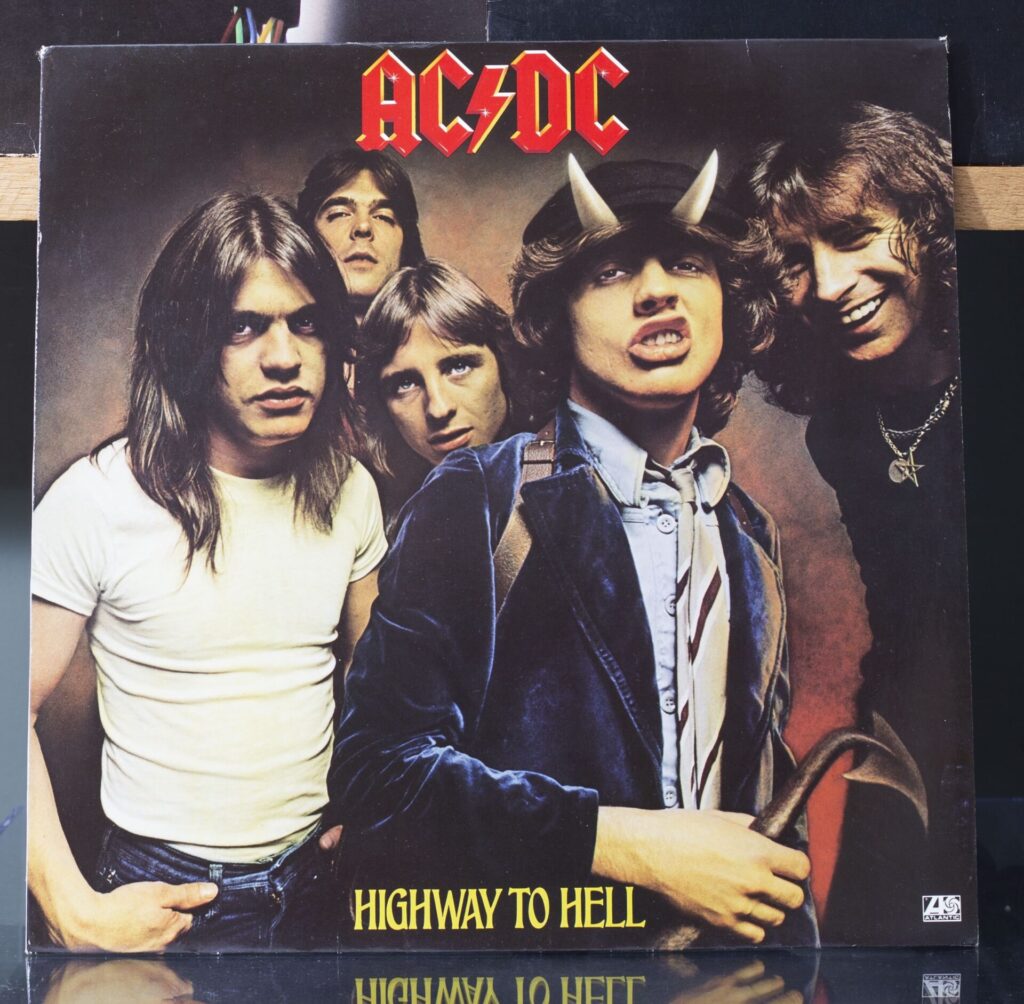

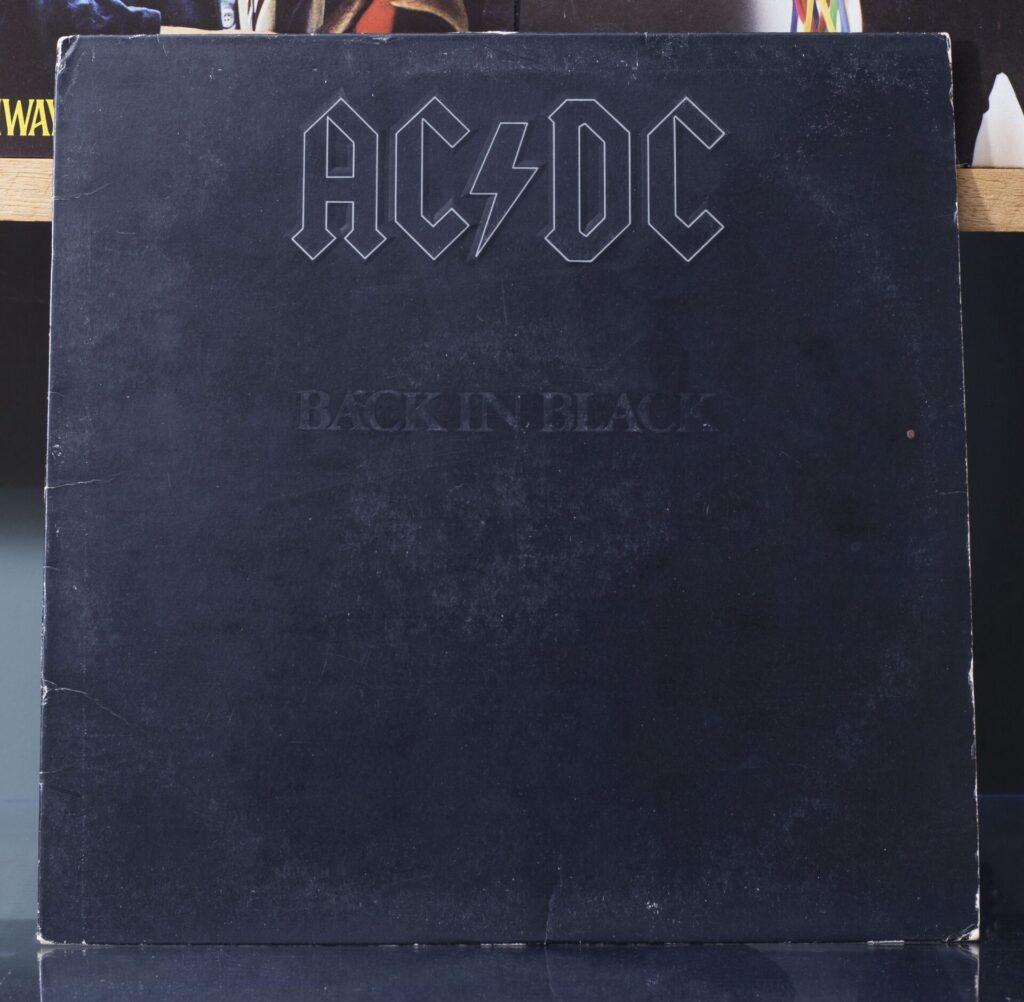

In this same three year period, this gang of refugees and townie last-chancers would produce a three album run (Powerage, Highway To Hell, Back In Black) that together make up the pinnacle three-LP run in all of 20th Century rock. If, within that category, those three albums are ever surpassed in the 21st Century, it’ll only be on account of some sort of reverse-Rapture scenario, where Hell is empty and all the rockers are here.

To avoid confusion, we should make clear that, when discussing the oeuvre and/or genius of Bon Scott, Malcolm and Angus Young, Phil Rudd, Cliff Williams and (from 1980 on) Brian Johnson, the omission of “& roll” is intentional. Further, and perhaps most importantly, the term ”rock”, in this context is pronounced “rawk”. As in: the kind of rock that fits in no other subgenres, no other subcultures, and to which no “post-” could ever be reasonably applied. The kind of music – blues-based, booze-dependent, heroically-puerile (and vice versa) heavy guitar pop – that inspires teenage dirtbags to grow their hair to their shoulders and write a band’s name in an elaborate font on their jeans and sneakers. You know. Rock.

Also, for the purposes of this discussion, the 20th Century begins in 1970. Like they say at the zoo: everything up to then was just tuning up. (For those who might argue against a seemingly arbitrary distinction which conveniently rules out the Beatles and Stones, please consult the speech, regarding the 1960s, made by the Terry Valentine character in The Limey for precedent: ”It was just 66 and early 67. That’s all there was.”)

All the above qualifications might seem excessive, or even counterintuitive. But despite their own claims and not un-strenuous efforts to prove otherwise, AC/DC is a complicated band. The joke, bolstered by the band’s own statements, is that every song sounds the same. Malcolm Young used to respond to the critique with, “Yeah, it’s the same band.” Over the years, lead guitarist Angus has told (and retold) an anecdote where some effete and impudent critic tells him that AC/DC has just remade the same album twelve times and he responds with, “That’s a dirty lie! We’ve remade the same album fourteen times!” The exact number of redone albums goes up as AC/DC persists, with the current anecdotal claim-to-truth ratio standing at 16 to 18. With all due respect to the Young Brothers’ self-effacement, the claim is provably false. If every AC/DC album sounded the same, AC/DC would have more great albums. Nor can the varying quality of the band’s catalogue be reduced to anything so simple as “is Phil Rudd playing drums on it,” at least not while ‘Thunderstruck’ exists.

Conceding that, within the confines of Bon Scott and Brian Johnson’s vocal range and Angus Young’s dogmatic attention to both guitar tone and fan expectation, and conceding further that the bloozehammer workouts and assorted dross which makes up a fair amount of the band’s catalogue can indeed blur together, I’d argue that every good AC/DC album is different. Ineffably maybe, but just as often quite tangibly to anyone who can, say, tell the difference between Slayer and Metallica LPs. Whether it’s the bagpipe dirge attached to the song which put AC/DC on the map in Australia, the proto-Oi! of Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap, or the bullying and steely gloss of the, ‘We still got some juice’ albums (1990’s The Razors Edge and their most recent, post-Malcolm, album) each with its own individual charm, sad-sleazeball concerns, and highway star power.

AC/DC’s diversity is nowhere more apparent than on the band’s three greatest achievements. If there’s an overriding unity to Powerage, Highway To Hell, and Back In Black, it’s in how all three signify a band that – inadvertently, temporarily – have gone from being cheeky traditionalists to being modernist in a way that Warhol would appreciate (if he could get past the t-shirts) and that a band like DEVO could only approximate when their songs started playing in Target ads.

Bon Scott’s voice, while overrated by Brian Johnson haters, was severely underrated when he was alive. In a direct line from John Fogerty, Rod Stewart, Family’s Roger Chapman (who he was negatively compared to in the States), and the various Australian acts who approximate the same, Scott was of the post-blues school of high-gruff authenticity mongering; what the wife calls “real-setto”. Love it, hate it, the little girls understood. That said, when people describe Bon Scott’s vocals, the term “vulnerable” doesn’t come up a lot. Yes, in various bios, the man himself is often described as having a raw sensitivity. But to be honest, these stories are usually very much in the “tell not show” category, following invariably as they do some story of the man being a complete fuckhead to one woman or another. Still, the stories are all told by those same women so there had to be something there. And that something is almost on display on Powerage.

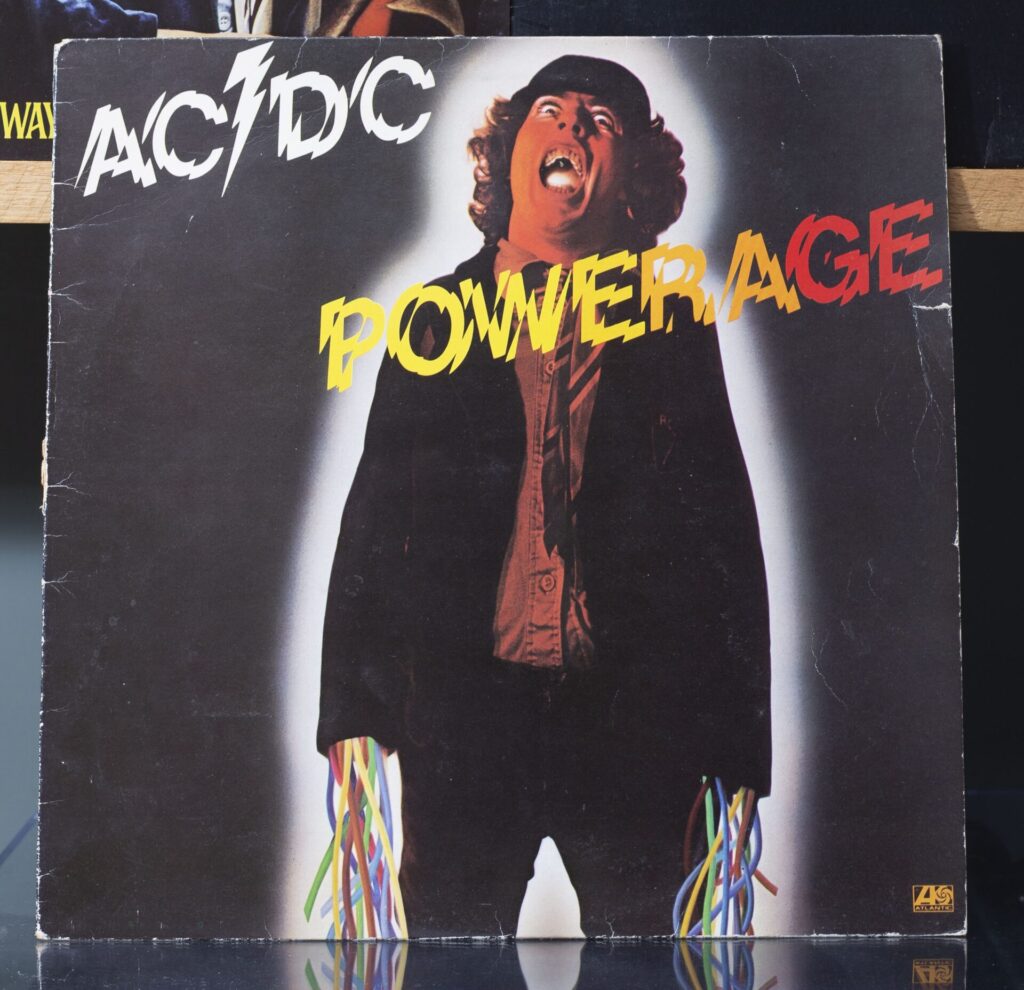

The album, the last one of the 1970s that would be produced by George Young, has no “hits” and peaked at #133 on the American charts. The album that hipsters, poseurs, and rock critics swear by, correctly. It’s the album where Bon Scott sounds the least cartoonish, the least tethered to blues traditions, the least tethered to anything really. On ‘Rock And Roll Damnation’, ‘Down Payment Blues’, and ‘Sin City’, he sounds so much like a man trapped within rock’s underbelly and hard rockin’ circumstances, hellbent on getting through (as opposed to be The Hardest Rocker Who Ever Rocked) that he’s practically a Mekons lyric.

It’s no mystery that Powerage is also beloved by skinheads, who always saw AC/DC as part of the Oi! lineage, both for the band’s working class bonafides and by dint of the band members being at least skinhead adjacent when they were sharpie tweens. Having a song like ‘Kicked In The Teeth’ is almost gilding the lily in that regard, but AC/DC were always both self-aggrandising in the violence they were willing to get into (the biographies are positively exhausting about it) and also more truthful than most tuff bands in how they made the violence prosaic, in the way they made taking a punch something so everyday that metaphors of violence were no different than catching a social disease or falling in and out of something akin to love.

Keith Richards, a man guilty of being hip if nothing else, is a noted Powerage fan as well. The album came out in 1978, just a couple months too late to have any influence on the Stones album which came out a few months later. So that explains why Some Girls isn’t as good as Powerage. Keef just hasn’t heard it yet. But then, the question lingers: what does Keith Richards hear that he loves enough to listen to while he’s mixing Stones albums? If he hears what we hear, why doesn’t he… do that? The wavering, breaking-on-the-shore riff of ‘What’s Next To The Moon’ could be the backbone of an Archers Of Loaf song. It could be a chorus on Immortal’s Heart Of Winter. How the fuck does the guy who’s written some of the finest music of the last 1,000 years hear that riff and go, “You know what, me matey? I think I’ll make Steel Wheels.”

The title track of Highway To Hell is a rewrite of ‘Hard Road’, a song which George Young wrote for the singer of the Easybeats solo album (which Malcolm Young played on), but when it came to the production job, the elder Young (along with his partner Harry Vanda) was still given the shaft in favour of Shania Twain’s future ex-husband anyways. Insisted upon by Atlantic Records but (grudgingly) agreed to by Malcolm and Angus, that kind of fraternal loyalty might be why “friends” is the first word on the record that Bon Scott bothers enunciating, like he’s manifesting camaraderie and putting out an open invitation at the same time. Richard Ramirez took the album’s closer, ‘Night Prowler’, as an instruction pamphlet, further illustrating one of the dangers of assuming everyone is on the same page. The band’s sixth studio LP is the first AC/DC album without a single song with a variation of “rock” in its title. Even without the signage, it got AC/DC to the top. Released the same week as Chic’s Risqué, scientists would designate those seven days as the horniest that the Earth’s surface had ever been, noting that it was a wonder that anyone made it to the end of July alive.

Joe Bonomo calls the album “rock and roll platonism”, which is a great line which would be true if anything else before or after sounded quite like it. Let’s be honest, ‘Drift Away’ is the platonic rock sound: sentimental, sloshing, unwilling to ever shut the fuck up about itself. This, thank God, ain’t that. Instead, for good or ill, thanks in part to a need for a hit and the ensuing Mutt Lange production, thanks in part to the crystallised distalization of all the previous albums’ cartoon venom (each song taking its own mean time without ever dragging), and thanks in part to ten tracks of the kind of Lego-perfect guitar architecture which left The Clash with no direction to go but roots and Led Zeppelin no choice but to give up entirely, Highway To Hell is the platonic AC/DC album.

For proof of the album’s singularity, look no further than the number of attempts there have been to cover the title track, with a failure rate of 100%. AC/DC covers are always iffy, with the smart move being to just winkingly paraphrase their whole thing (a la the Upper Crust) or taking The KLF’s advice and trying your best to sound like your heroes, hopefully ending up your own thing through failing (KIX, Dangerous Toys, The Godfathers etc). Once you decide to attempt an actual cover version, you’re on your own. Of all the ‘Highway To Hell’ renditions, Springsteen comes closest, on two versions, and neither gets within spitting distance of good. With the E Street Band, live in Australia, he performs the track like the least anonymous one-name band on any given 1980s teen sex comedy. When he chants “Australia” like it’s pronounced “get higher, baby,” you can picture Rodney Dangerfield tugging at his collar in bemused appreciation. The version with Eddie Vedder and Tom Morello is fun mainly as a nice illustration of just how hard it is to pull off Angus Young riffs and not sound like you’re using a 90s metalcore preset. As you can imagine, Vedder and Springsteen singing together, aping Bon Scott, sounds like two clams sucking on the same pearl.

I’m not trying to be cruel. Good on the whippersnappers for trying. But it’s not like “I tell you, folks, it’s harder than it looks” wasn’t on the syllabus.

It’d be cute, at this juncture, to say something about Bon Scott achieving his final form, or accomplishing what he’d set out to, or some such bullshit. But he was a human being, no more full of life than anyone else, but indubitably alive, wild, addicted to alcohol, and special. Again, maybe no more than anyone is but, if we are going to imagine art as something different than data entry (or, say, art criticism), the math is in his favour. That said, it’d have been better if he’d not made a masterpiece and lived. But what can you do?

Bores (of both the classic rock and alt variety) will smugly claim that when Bon Scott died (from something… opinions vary) on 19 February 1980, the band lost its soul. Rick Rubin, the Beastie Boys, and multiple generations of gum-chewing back-sassers, smoking Camel Lights in high school bathrooms all over the world would beg to differ.

Of course, depending on whether one subscribes to the theory that an amount of Back In Black was derived from notebooks of lyrics that Bon Scott left behind, the point may be moot. Without wading too deep into that controversy, I’ll simply say that I believe that every human being has a “she was a fast machine, she kept her motor clean” inside of them, most single cell organisms could have written the lyrics (if not the hook) to ‘Rock And Roll Ain’t Noise Pollution’, and if it’s hard to parse that the same person who wrote ‘Back In Black’ wrote a song as infinitely moronic as ‘Night Of The Long Knives’ just a year later, well, sometimes it takes a few years for thunder to strike twice. What matters is that, against all odds (regardless of the individual contributions), Back In Black happened. And teenage sass would never be the same.

If Bon Scott – poured into his jeans and wailing his auto-asphyxiated odes to desire and frustration – paved the way for artists ranging from Axl Rose to Blood Brothers (and Fugazi’s Guy Picciotto, if we grant the lasting impact that his first concert, AC/DC opening for KISS, may have had on him, and if we consider the timbre of his voice and think of a basketball hoop as essentially the same as a pair of tight pants), then what Brian Johnson paved the way for was everybody else. As with all the great supposed everyman arts, Johnson’s charm is making something very difficult to do (well) look easy, with the “well” part paved over in the invitation to sing along. If Brian Johnson was just a journeyman who lucked into the gig of a lifetime (and then kept the gig by doing what Malcolm Young told him to do), that would only serve to make his performance on Back In Black that much more remarkable. Like one of those moms who lift up a car to save their kid; at worst a tool as necessary as Angus’ Gibson (or a freakin’ howitzer on D-Day). But in reality, the fact that Johnson was able to step into a dead man’s shoes, not pretend otherwise, and do so in such a way that was not only seamless, not only knowing and affectionate, and not just boisterous but lovable (in a way that made a band, not previously known for being lovable, the same), proved the new belter to be less a tool than a superhero. (Of course, if Captain America lifting Thor’s hammer was delightful in the comic books, it became significantly less so as spectacle. But that came later.)

This is not to imply that Back In Black is sentimental art. It was indeed morbid, tough and caustic, and occasionally cruel, and the notion that this brand of sexism would seem a bit quaint thirty five years later probably wouldn’t have been much comfort for the women turning on the radio in 1980 to hear their genitalia described in terms of auto repair. One shouldn’t retcon Brian Johnson into the role of hard rockin’ teddy bear just because in 2025 the lyrical default for most popular male singers is monstrousness.

In this, and without falling for the sucker’s gambit of thinking of “punk” as an inherent good, if the punk designation – given to the band when they first hit the States and toured with the Dictators – was proven nonsensical by Powerage’s strange death-march blues, it started to make sense again with Back In Black, though by then the battle lines were drawn too deeply for any critic to make the mistake of calling something as it actually was. In retrospect it’s pretty easy to see that those carved off walls of noisified funk – as much proto-Page Hamiliiton as they were bastardized R&B – that Wilko Johnson excelled at (and passed on to Andy Gill) were never so far from the distorto brick laying of ‘Hell Ain’t A Bad Place To Be’ or ‘Girl Got Rhythm’, It’s not a reach to see ‘What Do You Do For Money Honey’ as the evil twin to any Gang Of Four song you care to mention. “We all have good intentions but all with strings attached,” just from a different moral angle. Sex as commodity, just rearrange the guitar bursts.

If the last couple paragraphs feel like denunciations, they are not. If the counterpoint of, “Ask a lady who loves AC/DC if any of that shit was remotely a dealbreaker”, seems anecdotal, bordering on hand waving, I would strongly suggest the reader consult with a female-identifying AC/DC fan, and see if you have a Geiger counter big enough to calculate the love that the band engenders. Or go listen to Nashville Pussy, or the first couple L7 albums. Or just go on Facebook and look up any of the girls you grew up with who were smoking at fourteen. The ones I knew saved my ass from getting kicked more times than I can count, so I’m loath to second guess their judgement. While no art is apolitical, there are albums that are soundtracks to simply shaking your shit which are… differently political.

And anyway, as stated up top, AC/DC are complicated. And simple. Primal I suppose, with the lizard brain mixed with a modernist individualism in such a paradoxically primitivist and highly refined manner that none of their contemporaries could touch. Maybe ZZ Top, but certainly not for three albums in a row. Maybe Van Halen, but only on 1984. Maybe Hot Chocolate, if they weren’t so patchy and/or people had better taste. Maybe the Sex Pistols, but for less than a full album. Maybe Led Zeppelin, on ‘Good Times Bad Times’, the first half of Zoso, and otherwise in their dreams. Maybe Thin Lizzy, but… ok, maybe Thin Lizzy too. All fine options, for heavy metal, or rock & roll, or blues rock, or whatever genre name one might apply to UFO, The Scorpions, etc. But for Rock? For RAWK? It’s AC/DC. It’s Powerage into Highway to Hell to Back in Black. They could’ve ended the century there. Everything that came after was sustain.

Three Album Run: Rules

- No live albums, no comps, no covers LPs, no collab records, no anthologies etc.

- Albums listed by year they were released not recorded

- No name changes unless name changing is part of the aesthetic. I.e. including albums by Tubeway Army and Gary Numan in the same run is not OK, but any permutation of the Osees as a three album run would be fine

- Album run has to start after 1970

- Ignore the band or artist’s feelings on what genre they are. The Cure are either goth, post punk, psychedelic rock or alternative rock. Sorry, The Cure!

- Even if we find the genre slightly spurious we’ll rely on main/leading genres provided by Wikipedia, All Music and Discogs. I.e. if Wikipedia say Roxy Music are “Art Rock” or “Glam Rock” then one of those two genres is what we’ll stick with; getting mired down in endless gatekeeping discussions over the authentic boundaries of genres ain’t for champs like us