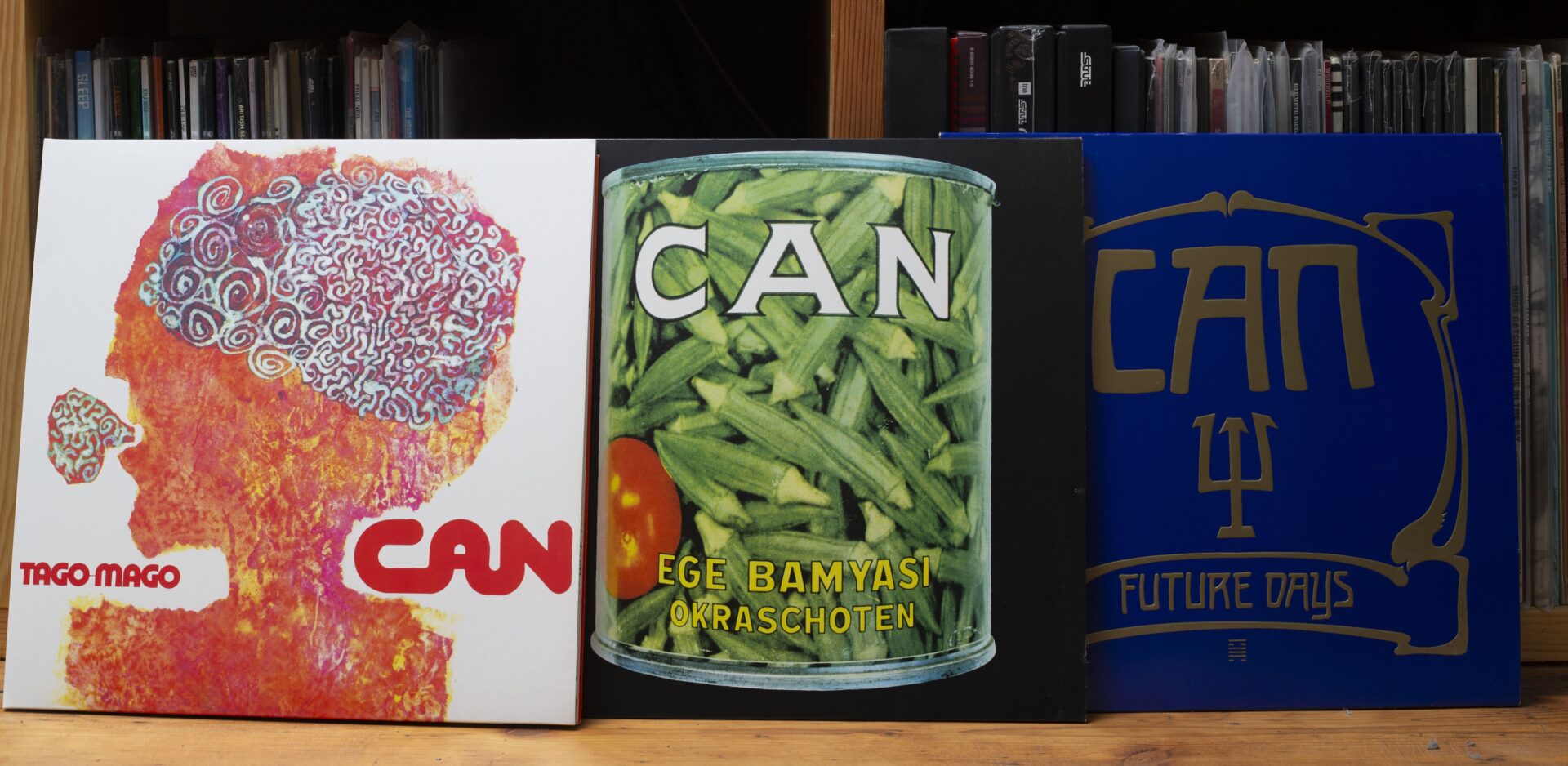

Three Album Run is a new series on tQ where we explore the best unbroken run of LPs in different genres. This month we open with krautrock but if you want to suggest a genre for a future essay please email John@theQuietus.com under the heading Three Album Run. The full rules are at the foot of this feature.

All cities are strange, in different ways and extents. Cologne is a place of time slippages. It’s not unique to find the strata of earlier epochs so visible in an urban landscape but it is with such intensity and oddities. Take the colossal Gothic spaceship-cathedral belonging to a distant grimdark future. Construction began in the 13th century, at the same time as the Seventh Crusade, while the Mongol Empire was in ascendency, and it was finished six centuries later in the days of electric streetlights, telephones and recorded sound. This is a city where teenage rebels named the Edelweiss Pirates, who seemed to augur a world yet to come, stood up to the Nazis and paid a terrible price. Cologne is a city where mosaic floors of Roman villas survive inside modernist buildings, where a bombed-out Madonna of the Ruins dwells in one sarcophagus inside another. This city where the cataclysms of history have impacted chronology itself, where you can see grafts, mutations, archaisms, cutaways in startling forms. In other words, it’s a place where it’s hard to avoid the utter weirdness of time.

It’s fitting then that Cologne is the birthplace of a band as mercurial and temporally subversive as Can. In some ways, Can could only have come about at that historical moment. Formed twenty-three years after the war, they were part of the cleansing and restoration of culture undertaken by young Germans sickened by what came before. Given the abyss of the Third Reich, in which so much and so many were irretrievably lost, there was no chance of returning to a Weimar-style cultural climate but elements of the spirit survived – a degree of transgression, radicalism, a sense of looking outwards, a receptivity to the ‘decadent’ (from the outer fringes of jazz to avant-garde art to polymorphic sexualities), a dismissal of ‘purity’, which had proved so ruinous, in favour of shapeshifting alchemistry and experimental openness. After the war, there had been movements of Trümmerliteratur (‘rubble literature’) and Trümmerfilm (‘rubble film’) in Germany, and though Can were retroactively assigned the loose category of krautrock (by journalists writing from a distance) or the constellation of kosmische musik, there was always an element of rubble music to their process, taking fragments of existing, disused or cast-off forms and combining them with technological innovations. Strange musical shapes began to form in the process that have been long since emulated but rarely surpassed.

Other German bands of the time (Kraftwerk, Neu! etc.) sounded like the future. Yet now the whooshing synths and strident motorik resemble the future as it used to be, with an unexpected comforting nostalgia. Can were different and remain so. They were anachronistic. The Antikythera Mechanism of bands. No matter how many listens, it’s still scarcely conceivable that these albums were made when they were (1971-73). They’ve never lost their beguiling WTF!? quality. Their influence has been colossal, and it seems simply that Can were way ahead of their time. Yet it’s weirder than that. Can’s influence is expanding with time, like the discovery the universe’s not just expanding but that the expansion itself is accelerating. If Can were simply ahead of their time, like Kraftwerk or Neu!, when exactly did we catch up? Why do they not yet feel similarly retrofuturistic? The truth is we haven’t caught up with Can, and there is less and less chance of us ever doing so, because they’re outside of time altogether. Or at least our conception of it. At their best, this is a band who show ideas of logical progression and musical evolution, obsessions with categorisation and genres, know-it-all expectations and explanations, to be limited, if not futile. If this is “kosmische musik”, as is claimed, it’s worth remembering that in space there is no absolute north. Everything is relative and earthbound compasses are of little value.

The trilogy began and ended with Damo Suzuki. It started with the band chancing upon the Kobe-born musician singing in idiosyncratic fashion on a Munich street (“praying to the sun” as Czukay would recall) and finished with the singer leaving to join the Jehovah’s Witnesses, providing a neat triptych to frame the (managed) chaos therein. The music is rarely formless, being sculpted judiciously down from lengthy improvisations. At times, it can be a challenging listen. There’s little of the locomotive paths of Neu! or Kraftwerk, the oceanic and celestial atmospheres of Harmonia or Tangerine Dream to submerge in, or the intercontinental mysticism of Popol Vuh to annihilate your ego to. Neither is there the sense of being lost in a hallucinatory commune of bad vibrations like Amon Düül II apparently were or the inevitably hit and miss exercises in collage and disintegration of Faust. It’s arguable Kraftwerk had a longer winning streak, from Autobahn (1974) to Computer World (1981), though with fewer turns and surprises, given their dedication to gesamtkunstwerk. If one band and one trilogy exemplified the ‘anything is possible’ side of krautrock, it’s Can during their peak.

Tago Mago, Ege Bamyasi and Future Days encourage a different way of listening to music; not in an affected, exclusionary way but an expansive one. As weird a departure as it is from the scaffolding of verse/ chorus/ verse pop music, it is nevertheless hook-laden. As wilfully undisciplined as it is compared to classical music, it borrows techniques of building and releasing tension. Instead of virtuosity for virtuosity’s sake, less is often more with Can. So raw is their approach, pushing against their training, they feel like the world’s greatest weirdest garage band. Yet the way band members fall in and out of the music, creating space and layering at different moments, is distantly reminiscent of jazz. Every component serves the whole, rather than showboating, making it more akin to the groove and texture-based compulsion of, for example, Miles Davis’ In A Silent Way than the time signature-obsessed onanism of prog. Yet it was their misfit category-defying quality that’s allowed Can’s work to remain so eccentric and vivid, revealing in the process how the categorisation of unpredictable art and artists is often an unnecessary attempt to herd cats, as restricting to the listener as the musician. While producing some of the greatest heights of krautrock, they not only transcended the label but revealed its innate paradox – if krautrock meant anything, it meant being uncontainable.

It seemed like anarchy at the beginning. Lionized now from a safe distance, Can’s debut performance with Suzuki, entirely improvised, resulted in audience unrest and a mass walk-out. One of those who remained to the end was, bizarrely, the dapper veteran actor David Niven who, when asked what he thought of the music, replied to the effect, ‘It was fascinating but I’d no idea it was music.’ Sounding like chaos, as Niven was canny enough to recognise, is no grounds for dismissal. Chaos theory is, after all, about noticing patterns where it might be assumed there are none. These are easier to see in the band members of that period than the music. The polyglot fragmentary lyrics of Damo Suzuki, the tech boffin Holger Czukay, the boy wonder guitarist Michael Karoli, the composer-experimentalist Irmin Schmidt and, at their core, a powerhouse drummer in Jaki Liebezeit. No matter where they roamed sonically, there was an immense gravity present where they could orbit, thanks to Liebezeit. It’s a contradiction to say he was their secret weapon, given it was a band of secret weapons. Instead, he was the reversal of the old idea of the soul in the machine. Though he aimed for metronomic precision, calling himself ‘half-man half-machine’, it came via breakbeats and shamanic pulses. Unlike much ponderous prog rock of the time, dancing was rarely far away.

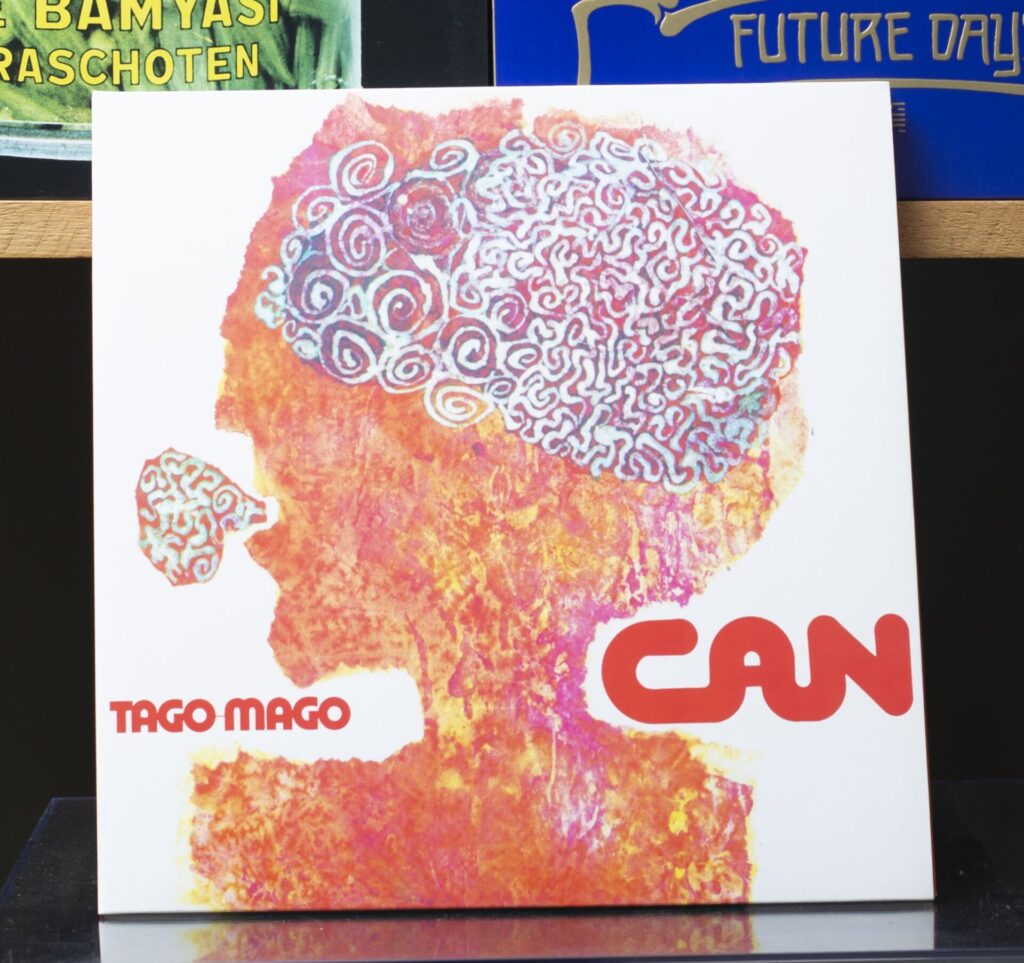

However convenient the triptych, the three albums are all divergent. Tago Mago was their magic album, according to the band, in chemistry and theme. It was named after an obscure Mediterranean island, Illa de Tagomago, where Liebezeit had once contemplated suicide during an ill-fated period drumming for a strung-out Chet Baker. The band explained the name in connection to Balearic magicians; the ‘Antichrist’ occultist Aleister Crowley (whose “Do what thou wilt shall be the whole of the Law” became a useful oblique strategy for the group); the mutable qualities of the sea; the conjuration of spells and encounters with witches during the recording sessions. Much of this was the result of mischief or misattribution but there’s a sense of remarkable synchronicity, indecipherability and flux to the recording. It’s a mysterious album from first notes to last. The best way to create art that lasts fifty years plus without losing its power is to create unanswerable enigmas.

Tago Mago was recorded in a castle, the Schloss Nörvenich, in a hall loaned to them by an art collecting industrialist, one of those rare meetings of different forms of freaks. They named it Inner Space. Suzuki would modestly call his cryptic lyrics and fractured way of singing ‘the language of the Stone Age’, which hid the meanings within them. You would have suspected listening to Suzuki’s introduction to the band (from the tranquil ‘Tango Whiskyman’ to the primeval ‘Mother Sky’ from their exceptional odds and sods collection Soundtracks) that this was new territory. With ‘Paperhouse’, it’s undeniable. At first, the title seems fantastical or childlike but the music and vocals becomes more frenzied, the glistening sway turning vicious, escalating into a delirium. It’s like a musical reproduction of the album’s expressionistic brain-frazzled xenoglossy cover art by Ulrich Eichberger, yet no mystery is meaningless. Suzuki was from a country where some houses are made from paper. Escape is key here, as the title of the album suggests, but escape can have many forms and destinations. A paper house could fly or burn, just as the Illa de Tagomago was both a pleasure island and a place that Liebezeit considered throwing himself permanently into the sea.

One astonishing song bleeds into another. When ‘Mushroom’ is discussed, it’s almost always because of Jaki’s bravura performance, an organic precursor to so much electronically sequenced dance music. Yet the song is vantablack in its darkness, a nightmare evocation of the atomic bombing of Japan, “When I saw mushroom head/ I was born and I was dead”. Its true heir is the post punk danse macabre of ‘Transmission’, ‘Death Disco’ and ‘Six Six Sixties’. All the members of Can were impacted by the war and its legacy, but luck and survival were common denominators. Due to last minute intuition by his grandmother, Czukay, along with the rest of his family, fled Gdansk in January 1945 by train instead of boat, despite already having tickets, narrowly avoided ending up at the bottom of the Baltic Sea like the 9,343 people who died when the MV Wilhelm Gustloff was sunk by a Soviet S-13 submarine. Czukay’s family then had to hide their Polish roots under a new identity. Liebezeit lost his father during the war, following persecution by the Nazis, and was displaced and poverty-stricken for years. Suzuki’s Kobe, like Liebezeit’s Dresden, was extensively firebombed (see Grave of the Fireflies). Change and movement were already so integral to the extent that these two qualities became the band’s reason to exist and guiding principle. Change is never more evident than in ‘Halleluwah’. Similarly held together by Liebezeit’s inventive infectious beat, ‘Halleluwah’ feels bathed in sunshine compared to the blasted moonscape of ‘Mushroom’. It’s not conventionally optimistic but there’s an ecstatic quality to the way it morphs, the way the drums recede and return, the way it feels so inorganic yet soulful. It’s as if they predicted electronic music fifteen years ahead and were sketching the vision on drumskins, bass notes and violin strings. A whole album side passes and it feels always just beginning.

Between the tracks is arguably Can’s finest moment, ‘Oh Yeah’. It’s essentially a trance, following Lennon’s invitation to, “Turn off your mind, relax, and float downstream”, but leaving out the relaxing and floating. Here we find another superlative example of the genius of Liebezeit’s self-declared dedication to monotony. It’s mesmeric, uneasy (the backwards voices are Lynchian) and gripping. It’s a post-psychedelia song of motion but where Kraftwerk and co feel like they’re going somewhere, the journey of ‘Oh Yeah’ is not outwards. Instead, its momentum pours inwards towards some kind of event horizon (the track begins with the explosion that ends the atomic apocalypse of ‘Mushroom’). At times throughout, it’s unclear what instrument is even being played. What sounds like nonsense lyrics in English and Japanese are anything but, with Suzuki channelling acid casualties and hungry ghosts. It takes real skill to sound this freeform. To this listener at least, ‘Oh Yeah’ is the highlight of their career and virtually anyone else’s.

Where it all leads is to the soundworld of the second half of the double album. Initially treated as tape experiments, Hildegard Schmidt persuaded the band to include them, and they remain the most out-there of their recordings. Clearly influenced by Stockhausen, under whom several members had studied, they are an extended coda, suggestive of but not as essential as the ambient sides of Bowie and Eno’s Berlin albums, featuring found sounds, Gregorian echoes, and ‘kids let loose in a music room’ tinkerings (you ‘play’ in a band after all). Stockhausen would come to their defence, writing in support of Suzuki who’d been arrested by immigration police, “Society dearly needs birds like these”. The tracks are more atmospheric musique concrète than the pseudo-Eastern mysticism they might be aiming for, though the band respawn for the pleasing closer ‘Bring Me Coffee Or Tea’. They are, however, the most overt example of the band’s move towards abstraction. Inspired by the likes of Miró, Kandinsky and co., there’s always an element to Suzuki-era Can, that was interested in shaking off the tyranny of meaning and moving towards sonic worlds existing in and of themselves. This would inspire later bands like Talk Talk and Radiohead to partially free themselves of the strictures of songwriting and the claustrophobia of ‘the message’, whether love or politics. And they would pre-empt non-representational electronic and ambient music, with its liberating emphasis of being over declaring a meaning to the listener. In this sense, Can were harbingers of magic, if its definition is the point where rationality is no longer a sufficient guide.

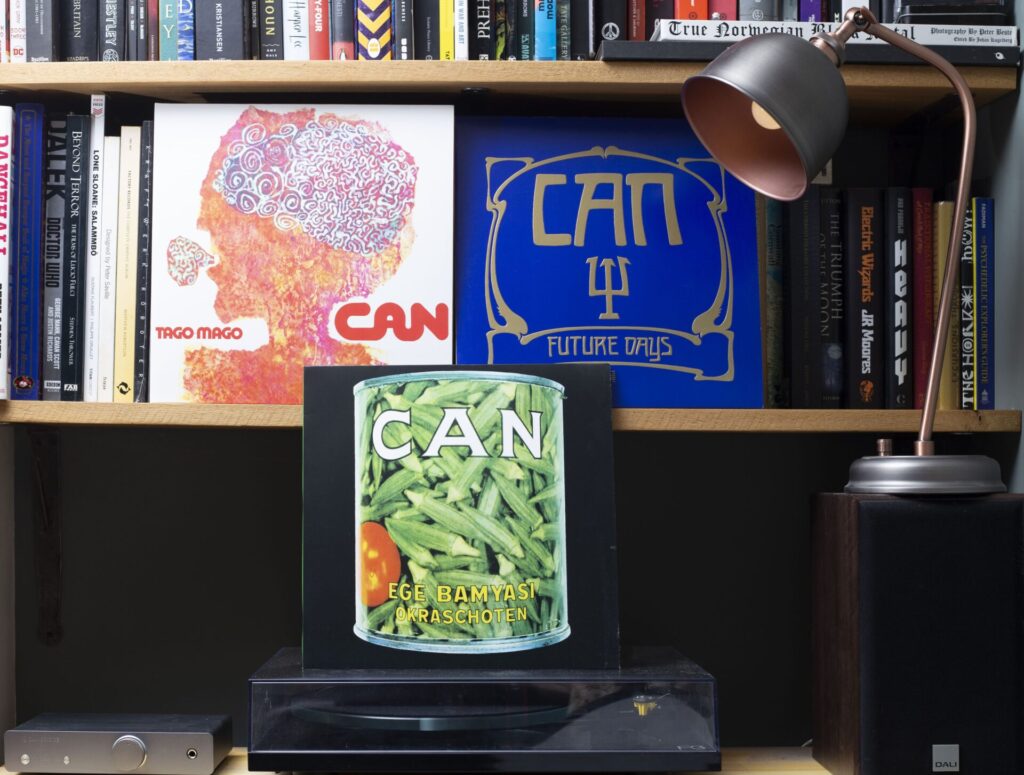

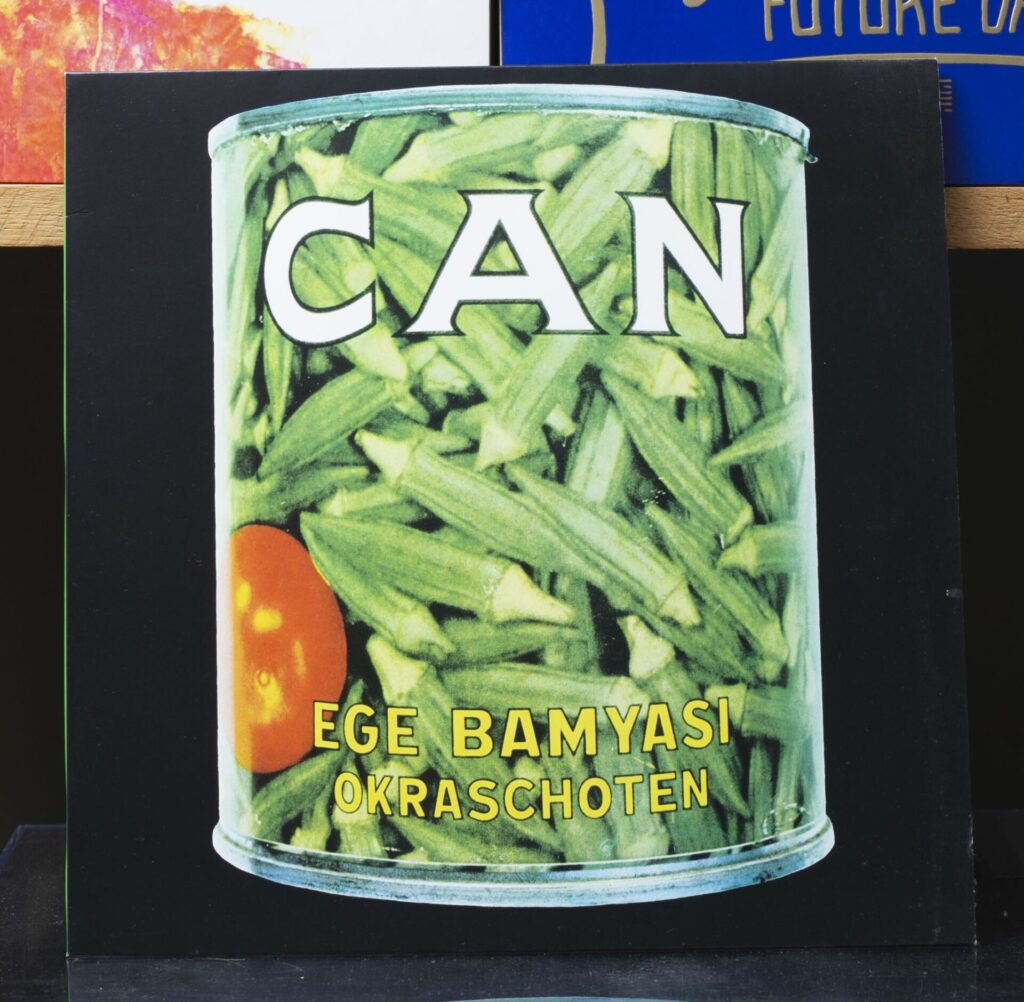

Moving their headquarters from castle to disused cinema, Can produced as close to a funk album as they ever got, Ege Bamyasi. By their admission, they’d been influenced by the likes of James Brown, Sly and Family Stone etc but, akin to Talking Head’s mimicry of Fela Kuti on Remain In Light, the German-Japanese interpretation of funk was unexpected. It’s certainly their tightest and most focused of the three. If Funkadelic looked like funk from another planet, Can sounded like it. It begins where Tago Mago left off. ‘Pinch’ feels nebulous, form-seeking, a continuation, erupting into feedback squalls and post-punk thrashing before there was punk, but it’s a false start. The album really emerges from the babbling brook that begins the riparian ‘Sing Swan Song’, which waltzes its way between romance and requiem. ‘One More Saturday Night’ is smooth future lounge music, tethered only to the time of its making by Karoli’s blues licks. Metronomic here, Liebezeit will later steal the show, alternating between street jazz shuffle and full-on Doctor Octopus drums. The eternally fresh ‘Vitamin C’ and the woozy ‘I’m So Green’ are concentrated examples of that astonishing, ‘Which decade produced this?’ quality. The former was my first encounter with the band, watching breakdancers spin to it, a quarter of a century after it was recorded. ‘Soup’ is an unhinged confrontational journey, capturing the more abrasive elements of their live show. The album finishes with one of the most unlikely hit singles, ‘Spoon’, written as the theme music for a popular TV thriller, made all the more unlikely by the fact that the band were not surprised by its success. Can, it turned out, had been trying all along to be commercial, raising the intriguing counterfactual of a world in which this band was mainstream.

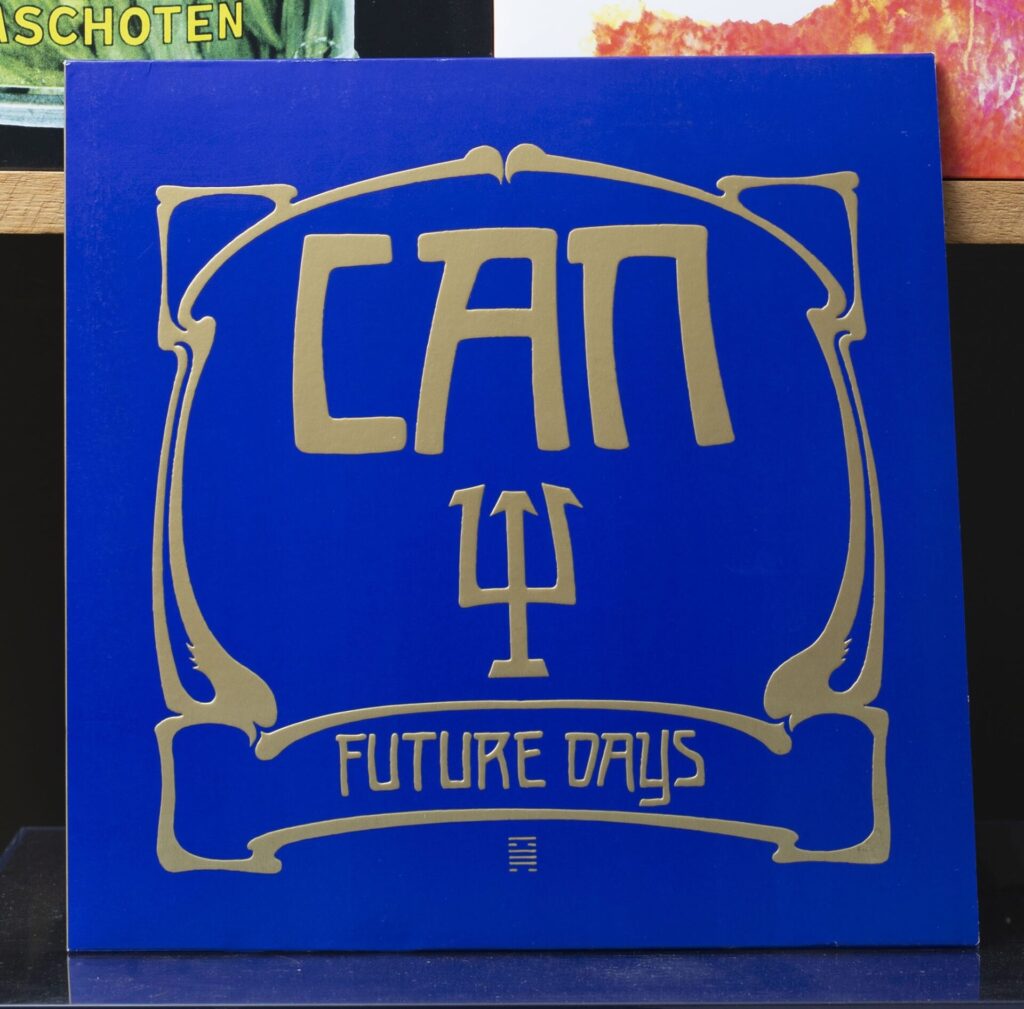

Future Days is the least well-known of the trilogy and the most cinematic. It is also their botanical album. It begins as if emerging from the sea at night onto a pacific jungle island, hearing a calypso groove through the tropical birdsong from a fire in a clearing. This is not exotica though so much as the vernacular music of an undiscovered planet, less Les Baxter and more Ursula K Le Guin. With typical surprise, the mood changes from blissed-out ambience to heightened tension, with Suzuki’s phrasing effectively birthing Mark E Smith, though it’s more Solomon Islands than Salford. ‘Spray’ continues the feeling of being lost on an alien forest moon, finding a path through the dense undergrowth two thirds in. The robotics return with ‘Moonshake’, possibly their catchiest song. As with the propulsive closer ‘Bel Air’, it’s still laden with effects that match the alien flora and fauna elsewhere on the album.

Suzuki would leave not just for religion but because Future Days had cured him of the impulse to make music (for the time being), “Nobody else arrived at such a space” he claimed to Terrascope, “It’s just a new dimension. With that album I was really free, it was no longer necessary to make music after.” He would return to shapeshift with assorted musicians for many years, in a succession of uniquely strange cities. Can would continue with the underrated Soon Over Babaluma but subsequent albums would feel relatively conventional, as if whatever was original and unusual had solidified. The band would later lament becoming more proficient instrumentally, recognising that brilliance lay in blissful ignorance. Any dissection of why this trilogy has proved so influential to so many artists, in wildly divergent genres, would be wasted. What matters is what the intoxication they capture, of setting off into terra incognita without any maps.

Sign up to tQ’s free weekly Digest Newsletter for future 3LP features and much more

Three Album Run: Rules

- No live albums, no comps, no covers LPs, no collab records, no anthologies etc.

- Albums listed by year they were released not recorded

- No name changes unless name changing is part of the aesthetic. I.e. including albums by Tubeway Army and Gary Numan in the same run is not OK, but any permutation of the Osees as a three album run would be OK

- Album run has to start after 1970

- Ignore the band or artist’s feelings on what genre they are. The Cure are either goth, post punk or alternative rock. Sorry, The Cure!

- Even if we find the genre slightly spurious we’ll rely on main/leading genres provided by Wiki, All Music and Discogs. I.e. if Wiki say Roxy Music are “Art Rock” or “Glam Rock” then one of those two genres is what we’ll stick with