I was months into trying to find out more – or anything – about a German cellist called Anja Thauer and my focus had changed to her mother. Ruth Thauer had been a professional musician too – a violinist who had cut her teeth in Leipzig’s vibrant music scene before the Second World War. She doesn’t bring up a single Google result, but dig into archived German newspapers and music magazines and there are plenty of listings for her concerts and tours. Those listings stop in 1939, when she was 32, and I wondered why. The war started, but an expert on music under The Third Reich, Professor Erik Levi, had told me in an interview that it was very much business as normal for working musicians, and for quite some time. Ruth had either chosen to quit or she was forced to. Which one? I’d begun to think that answering that question was the key to understanding the complex relationship she would go on to have with her only child Anja, who was born in 1945.

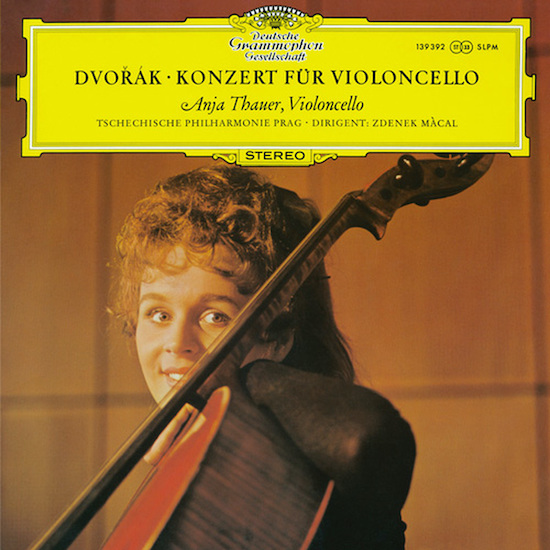

The story of Anja Thauer started for me how all of these Junk Shop Classical stories start – in a charity shop. In 2018, I found an old record of Thauer playing the Dvořák Cello Concerto with the Czech Philharmonic conducted by Zdeněk Mácal. It was from 1968. I’d never heard of him, or her, despite the album being released by the powerhouse German label Deutsche Grammophon, home of so many of classical music stars of that era and today. Intrigued, I bought it for a quid and was shocked to learn that Thauer had died so young. She has no Wikipedia page in English, just a tiny, seven-line page in German. “Im Alter von 28 Jahren nahm sie sich aus Liebeskummer das Leben,” it says, or, “At the age of 28, she took her own life out of lovesickness.” She’d been having an affair with a married doctor in Wiesbaden, where she lived, and he’d committed suicide too, five days after her.

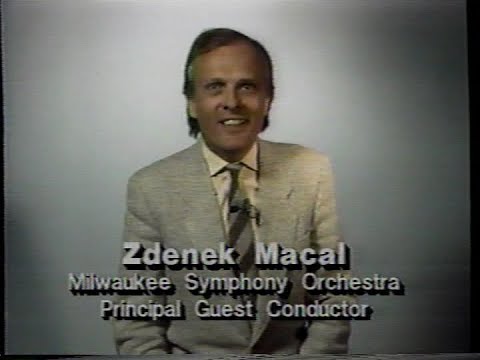

Thauer’s performance of the Dvořák Cello Concerto is of its time, and I don’t mean that it’s dated. It’s robust and full-blooded, constantly teetering on the edge of collapse. Only young musicians dare to play with that kind of near-reckless passion and Thauer was 23 when it was recorded – in Hamburg, in a studio that that The Beatles had used when they were in the city a few years previously. Most likely, the Czech Philharmonic were on tour in Germany and Deutsche Grammophon thought they’d make a good pairing with their young firebrand cellist. But exactly how the recording came about has been lost to time – not even Zdeněk Mácal remembers. Wonderful guy – 83 now, long retired – but his memories of the 1960s aren’t perfect. “Aaaaaaah, it’s quite a long time ago,” he told me. “Nah, she was a wonderful girl, excellent cellist. ’68…. I was young. He he!”

To my amateur ears, that album captures the spirit of the age as effectively as any pop or rock record from the era does. It was recorded in March 1968, just as the student movements across Europe were beginning to flare up. By the time it came out at the end of the year, the lives of every member of the Czech Philharmonic were changed forever. On the night of August 20, Soviet tanks rolled into their homeland, crushing the Prague Spring. Maestro Mácal ended up in exile in Europe first, and made it to America eventually, where he worked, among many other jobs, as the music director of the Milwaukee Symphony Orchestra.

Zdeněk Mácal had a great career; Anja Thauer did not. Although she lived for five more years, she never recorded another album, although she was contracted to release two more. We know that because Deutsche Grammophon dug up her original contract for the critic Tully Potter, who wrote the sleevenotes for a 2015 reissue of the two albums she released on the label (a third album exists – a debut from 1962 on a long-gone indie called Attacca – but it’s rare as hen’s teeth). She was taken on by Deutsche Grammophon, and then pushed aside as the already famous Russian cellist Mstislav Rostropovich came to the label in 1968, just as Thauer’s Dvořák recording was hitting the shops. Classical music is no less ruthless than pop.

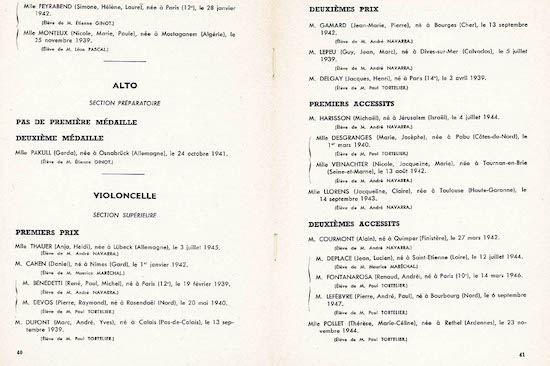

Tully Potter was my first port of call when trying to find out more about Anja Thauer. What started as cursory research for a possible tQ column became a BBC Radio 3 doc, The Myth And Mystery Of Anja Thauer. Potter was the first interviewee and his research tells us much, about how Thauer was born in Lubeck, moved around as a child, made her orchestral debut in Baden-Baden at 12, and then went to the Paris Conservatoire on a scholarship, aged 15. She won the top prize in her year for cello playing, the Grand Prix, before starting out immediately as a touring soloist, guesting with various orchestras across Europe and beyond, or playing recitals alone, or with pianists picked up locally in whatever city she was visiting. For Potter, this was a mistake. He believes Thauer should have played in a smaller, chamber music group first – a string quartet, perhaps – built strong friendships with the other members, and not have suffered the loneliness of the road at such a young age. But Thauer was ambitious, and that ambition had been thrust upon her by her mother after her own career had collapsed in 1939.

Potter said that Thauer had “a lonely childhood and a strict, domineering, even exploitative mother”. He’s not alone in forming such a brutal characterisation of Ruth. The producer of the documentary, Alexandra Quinn, contacted the pianist Claude Françaix, daughter of the composer Jean Françaix, whose music Anja recorded on her first and second albums. Claude toured with Thauer in the early-1960s and the two became close. She didn’t want to be interviewed, but she did send us a remembrance, saying: “Her mother projected onto her very talented daughter her own ambitions for an illustrious career. In certain respects, Anja remained a child dominated by her mother; l don’t believe she was ready to play the ‘diva’. She was essentially a very kind and simple young woman, obliged to project an image of herself that didn’t suit her very well.”

In 2008, a German cellist called Michael Schlechtriem posted about Thauer online and, afterwards, he was contacted by a friend of Thauer’s. He’s lost her contact details, but he remembers the conversation. “She told me that she was dominated by her mother and that she didn’t have any childhood and, at the end, she found the love of her life,” Michael said, adding: “And this woman, she didn’t know that Anja Thauer committed suicide, only that she was dead.”

That’s strange, isn’t it? How could you be a friend of a woman who died at 28 and not know that she had taken her own life? There were a few short notices and obituaries in German music magazines and local papers, but it wasn’t a big story. By 1973, Thauer was still touring, but not in major cities, and it had been five years since her last recording – the Dvořák concerto – had been released. Since then, not much interest either; Thauer remains a fringe figure in the history of classical music, despite the 2015 reissue of her Deutsche Grammophon albums and a small German label called Hastedt Musikedition releasing some previously unheard radio recordings from across her career, including Thauer playing the Chopin Cello Sonata with Claude Françaix.

The more I dug into the story of Anja Thauer, the more mysterious she became. There’s a school of thought that her chance of success was scuppered by the fame of the English cellist Jacqueline du Pré, an exact contemporary. They were both born in 1945, studied in Paris and the same time and, uncannily, both of their career ended in the same month – October 1973, with Thauer’s death and Du Pré’s multiple sclerosis diagnosis. Classical music was unquestionably dominated by male musicians in the 1960s, but du Pré’s biographer and friend Elizabeth Wilson told me that there were plenty of other women cellists on the scene at the time – Christine Walevska, Natalia Gutman, Karine Georgian – and geography was the most likely reason for Thauer not getting ahead. She was German and based in Germany at a time when London was “the music capital of the world”, and she also never played in America, which became central to raising du Pré’s profile to stratospheric heights.

Nonetheless, I wondered why Thauer remains so unknown. It’s unusual – unprecedented, even – for a Deutsche Grammophon-signed artist of that era to slip into such obscurity, especially one with such an extraordinary life story. The almost complete lack of information about Thauer out there became a source of interest in itself. My attention turned to her mother, and for that I needed help. I was locked down in the UK, so I asked Jeffrey Brown, a Berlin-based American journalist for the excellent online classical music mag Van, if he had time to help with some digging.

Ruth Thauer was a judge’s daughter – her father was the director of the State Court in Leipzig. And she wasn’t Jewish. Jeffrey got hold of the report card from the music school where she studied, the Leipzig Conservatory, and it clearly states that she was protestant. Her career was bigger than I’d first imagined. Before I interviewed Professor Erik Levi, he managed to unearth something that took us all by surprise – a glamorous, full-page portrait of Ruth (below) in a society fashion magazine called Der Silbenspiegel. It was from 1935, when Ruth was temporarily living in an affluent neighbourhood of Berlin and presumably playing concerts there. One newspaper report said she’d worked with two of the most significant conductors of the day – Wilhelm Furtwängler and Bruno Walter – but we couldn’t find specific listings, or anything concrete on her relationship with the Nazi regime. Was she a party member, for political or practical reasons, and might that explain why she quit music in 1939, other than playing a few post-war recitals with her daughter when she very young? We still don’t know, because the one document that would explain more about Ruth and her career under The Third Reich – her Reichsmusikkammer card, which all performing musicians had to hold under the regime – doesn’t appear to be in the public domain.

There’s nothing official about Anja Thauer in the public domain, either. Her musical papers – her nachless – are presumed to be in the possession of distant relatives, who might not wish to be associated with her memory, or the memory of her mother. That’s the belief of an amateur musicologist called Hans-Joachim Köthe – a 90-year-old former notary public who has been a member of the International Grand Lodge of Druidism since 1958 and has spent many years trying to find out more about Thauer. Jeffrey contacted him on the recommendation of a journalist in Lubeck, who had recently written a piece about Thauer in a local magazine, and then interviewed him at home in a village outside of Stuttgart. “With the help of the court, I was able to find these people,” Köthe said about the relatives. “The one person I reached became hostile. She said, ‘I see you’re trying to find out scandalous things.’ And I thought, ‘So that’s how it’s going to be.’ There was a rift in the family. Ruth Meister kept her distance from the others. She felt that she was superior to them.”

Köthe called Ruth “calculating and ambitious”. He believes that the affair Thauer had with the doctor, her GP, was an attempt to “get out of the iron grip of her mother” and that, after Anja’s suicide, Ruth attempted to keep her daughter’s career and the circumstances of her death out of the history books. Is that why Anja’s friend didn’t know that she had taken her own life? I’m not sure. Nor it is clear why Ruth would deprive her daughter of a childhood by driving her so hard in her career, and then effectively punish her to anonymity in death.

Ruth lost her only child and lived with the grief for her remaining 17 years. She suffered too, and she also lost her first husband – Anja’s father – during the war, before Anja was born. That’s another of Köthe’s revelations. Fritz Thauer, who was an engineer employed by Siemens, adopted Anja was she was about 10 years old. He seems to have been supportive, but he stayed in the background and died in 1980, 10 years before Ruth. The urns of the Thauers – a family line now extinguished – are buried in a graveyard in Travemünde, a borough of Lubeck. Last year, Köthe laid a memorial plaque there. Translated, the inscription reads. “A blessed cellist gave the world her gift. It shattered her. She became a myth in Japan.” It seems an odd thing to say at first, but during the almost-50 years since she died, her name has been kept alive by music fans in east Asia, who treasure Thauer’s recordings and will pay absurd sums for the original copies of the three LPs she released in her lifetime.