Getting over yourself is a lifelong job; you really have to keep at it, and most of us never manage. You might struggle, too, to work out what the difference is – practically speaking – between getting over yourself and just sitting down and being quiet. (You’d be in good company, and would perhaps make an excellent nun.) The fear, perhaps, is how do you get over yourself without making yourself disappear?

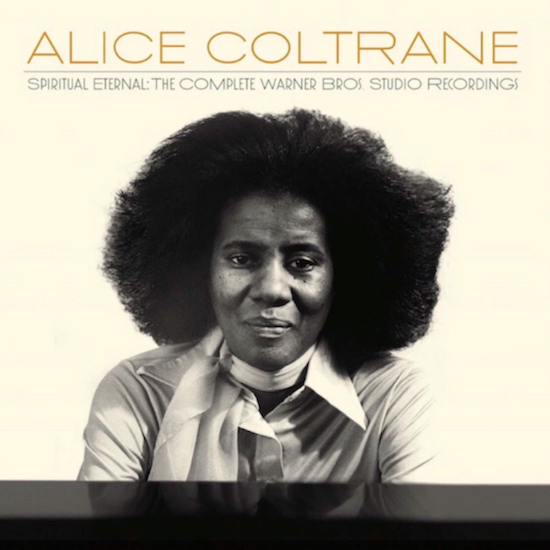

There’s no doubt that Alice Coltrane got over herself. She had help (though that might not be the right way to put it) when she was widowed aged 29 with four children to look after, her beloved husband killed by cancer. Grief can do amazing, terrible and bottomlessly strange things to you. In the period following John Coltrane’s death, the harp that he’d ordered a few months previously arrived and Alice began to play it. She also entered into what she described as her tapas – a period of spiritual cleansing – where she fasted, deprived herself of sleep, meditated, hallucinated, and was admitted to hospital after purposefully burning herself during "examinations" to see her body’s further reactions to extremity.

She also, like those modal chords, carried on going. Into the beyond, the unknown. Can you imagine? Four children, cataclysmic grief, and all the while continuing her lifetime of musical and religious exploration and making these records – those she made with Impulse in the years immediately after John’s death and the three collected here. There’s no point pretending – why would you pretend? – that this music is not a result of bone-deep spiritual richness and bravery.

Grief can have a powerful effect on time and memories, too – what once seemed linear can pile up perpendicular, like a city block in Inception, like Walter Benjamin’s Angel Of History ("Where we perceive a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe"). Alice Coltrane and John Coltrane had long been playing and working with time, and that playfulness took a new dimension after John’s death – and after Alice bought the Wurlitzer organ in 1971, with the built-in pitchbending synth, which for Alice offered the same meditative drone capabilities as the classical Indian shruti box. ("If you go to India or other parts of the East," she said in 1971, "they’ll use something like a harmonium, called a shruti box, to make a drone sound… that’s organ!")

Alice Coltrane’s approach to time reminds me of Kurt Vonnegut and his Tralfamadorians, in Sirens Of Titan and Slaughterhouse Five; they are, among other things, Vonnegut’s own generous, serious and playful response to grief. From Slaughterhouse Five: "The most important thing I learned on Tralfamadore was that when a person dies he only appears to die. He is still very much alive in the past, so it is very silly for people to cry at his funeral. All moments, past, present and future, always have existed, always will exist. The Tralfamadorians can look at all the different moments just the way we can look at a stretch of the Rocky Mountains, for instance. They can see how permanent all the moments are, and they can look at any moment that interests them. It is just an illusion we have here on Earth that one moment follows another one, like beads on a string, and that once a moment is gone it is gone forever."

Coltrane’s Wurlitzer organ

Coltrane’s musical path began as a gifted piano player and daughter of a Methodist family in Detroit; she moved to Paris for bebop, she developed new ideas about music and worship. But she never really moved on from things – she accrued, she gathered more collaborators, more ideas, more philosophies. On these three albums alone she plays with Charlie Haden, with Carlos Santana, with her 13-year-old son Arjuna John Jr on 19-minute duet ‘Om Namah Sivaya’ (and with John, really, on ‘Om Supreme’); she draws from her Methodist roots, from Hindu chants, Vedic bhajans and kirtans, from jazz, from rock, from Stravinsky, apart and all together. Music was universal for her, and as she got over herself she expanded and transcended to include it all. Spatially and logically, I suspect, you can’t expand and transcend – unless you have worked out how to expand and transcend space and logic, and probably time as well. That’s what she does. She rises above and she digs in – the deeper you go, the higher you go. Alice Coltrane is everywhere and nowhere in these recordings; she’s ego-less and grandiose at the same time and, rather than cancelling each other out, they work magic together.

Listen to ‘Spiritual Eternal’, the first track here. It “embraces the ancient soul of the immortal eternity”, Coltrane tells us in the original sleevenotes (reprinted on this new release). “It also peacefully rests upon the everlasting wings of the Eternal Endlessness.” That gives you some idea about her attitude towards time – which remains linear in this statement, kind of, but has a reassuring scale to it, don’t you think? It’s a grandiose statement and this is a grandiose song – it has brass (trumpets, french horns, trombones, tuba, flutes, saxophones, bassoons), it has strings (violins, violas, cellos), it has the great Charlie Haden on bass, and Ben Riley on drums. It begins with Coltrane on her Wurlitzer organ moving forever headlong into your hippocampus and the universe; the strings come in, at once a response to the cosmic Wurlitzer sounds and an all-encompassing encouragement of them. It is the most startling and natural combination, full of sass and swag. But whose swag am I hearing? Is it Alice Coltrane’s or is it mine? I don’t know. I know that on a meepy day you can self-medicate with this song; your chest will rise, your soul will hum and soar, you will smile all beatific. As a woman I met recently put it: “You listen to this song and you know you’re the bee’s knees.”

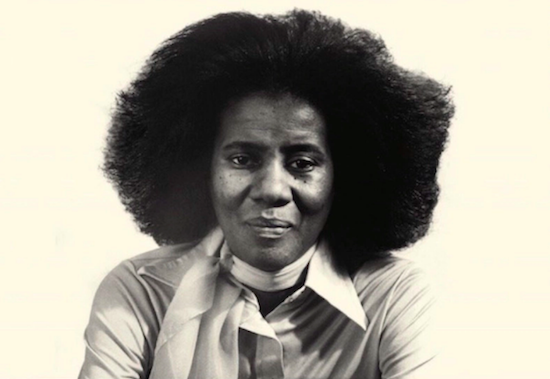

Photo from the Institute of Jazz Studies at Rutgers University

She is playing a 1971 Wurlitzer 805 Centura that included, above its two full-size keyboards, an Orbit III analogue synth. Which is perhaps interesting mainly because you can go and watch videos on youtube demonstrating this top-end domestic-market organ, $10k in its day apparently and a serious piece of home entertainment; you can boggle at the thought of middle-class groovesome Americans playing the behemoth in their front room, you can delight in the kitsch/muzak/Ed Wood vibes, so very distantly related to the sounds we hear in Alice Coltrane’s music. Here, the instrument (which she bought after seeing it in a vision during deep meditations) somehow holds on to all those 70s associations and then expands and transcends to make perfect sense when she plays it on Stravinsky’s ‘Spring Rounds’, on the Hare Krishna mantra; when she plays it alongside Charlie Haden’s upright bass, over and over again, and alongside Carlos Santana’s timbales on ‘Los Caballos’ – a song "dedicated to all people who like horses… and to all our horses, Chico, Bart, Loose, Joker, Peepers, Leo and Camelot Diamond Coltrane". (Is it crass to imagine what a planet-shaking relief it would be to have Alice here with us now? Perhaps we could do a swap – get one Alice back in exchange for a million of these dickheads.)

By the time she made the last of the songs included here, in 1976-77, Coltrane was moving further out of the music industry and deeper into her Sai Anantam Ashram. In a 2006 interview with Essence magazine, she said: "After fulfilling my Warner contract, I really wanted to go deeper into what the Lord had outlined for me to do. I felt that it was time for the next generation of musicians. And the music was changing, so I thought maybe my time is finished. Maybe this is sufficient."

And Alice was gone, from the industry at least. Luaka Bop brought us some of the recordings from the ashram on their The Ecstatic Music Of Alice Coltrane compilation last year, and she made one more studio album for Impulse, Translinear Light in 2004. But essentially I think she’d gotten over herself so hard that she disappeared: "…Maybe this is sufficient." She died in 2007 but, like the Trafalmadorians, I know she is very much alive in the past; I know that the moments and the music she made have always existed and always will exist. If that sounds ridiculous, so do these songs. They don’t though – they sound rock-solid real and they sound amazing, spiritual, eternal.