The United States – and its Anglo-European conspirators – has been striding headlong toward its reckoning for over four hundred years. Black people, and their allies everywhere, from Atlanta to Athens and Paris to Palestine, are joining together, once again, in the streets to overthrow this vicious white supremacist death march. The air is filled with chants, songs, demands, and incantations of the names of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, and countless other Black people murdered by the police and its white citizens. It is as if the dead are being called forth to guarantee this divine comeuppance.

Groups of people, many of them strangers the day before, reclaim public and private spaces – typically reserved to serve the demands of capitalist profit and police state power – and convert them into impromptu memorial sites and autonomous zones. Cop cars and fast-food restaurants burn. Monuments to slaveholding presidents, racist Prime Ministers, Confederate terrorists, British slave profiteers and genocidal conquistadors, are maimed, defaced or torn down with almost equal vengeance.

This "push back" should be no surprise to anyone, anywhere – even if the US has perfected, through every manipulation of the historical record, the conniving "art" of gaslighting huge swathes of the world into believing the opposite. After all, Black and other oppressed peoples have been struggling against the United States – European countries in tow – and its vicious pursuit of the twin killing engines of global colonial finance capitalism and white supremacist violence since the birth of this nation.

Shockingly, however, many mainstream white Americans, Europeans and the majority of their elected officials, remain in wilful, forceful denial. Utilising every recycled, racist turn of rhetoric, they seek to undermine legitimate forms of resistance by appealing to the preservation of public history or imposing false moral equivalences between state murder and destruction of private property. It is clear that the time for persuasion or pleas to morality is over.

As Atlanta’s Kimberly Jones has said: "The social contract is broken. You broke the contract when we built our wealth by our bootstraps in Tulsa and you dropped bombs on us, when we built it in Rosewood and you came in and slaughtered us. You broke the contract when you murdered us in the streets and didn’t give a fuck. And they are lucky that what Black people are looking for is equality and not revenge."

Algiers, as a band, were constituted in the Deep South where this all-so-American war on Black people has been vigorously and bloodthirstily pursued. It is this tandem operation of institutional violence and white silence – and our own personal experiences with it – that has influenced the political side of our art and interventions, along with artists such as Octavia Butler, John Akomfrah, Sun Ra and Frantz Fanon.

Juxtaposing geographic and architectural imagery with the poetics of Black and other oppressed people’s liberation enables us – taking the city once called the capital of global revolution as our name – to interrogate the ways capital and white supremacy encloses, colonises, erases, whitewashes and distorts every physical, institutional, psychological, artistic, and cultural space, even occupying our most cherished experiences of grief, history, leisure, art, and the future.

‘Blood’ explores the white-owned music and culture industry’s simultaneous appropriation of Black creativity and indifference to Black suffering, exemplified in the Cornell West quote: "The American mainstream is obsessed with Black music, walk, style, and at the same time puts a low priority on the Black social misery from which that creativity flows."

‘Irony. Utility. Pretext.’ simultaneously challenges Euro-American capitalist triumphalism and colonial conquest in post-Soviet Europe and Africa, physically repurposing socialist monuments in Bulgaria alongside quotations from revolutionaries to imagine a radical Fanon-inspired Afrofuturist space. 2017’s ‘Cleveland’ chronicles the age-old institutional murder of Black people, alongside images of Franklin in the Pink Houses and other New York memorial sites to Eric Garner, Keith Warren and others. ‘Dispossession’ initiates a search, without avail, of Paris’s banlieues and pristine streets, for memorials to the victims of France’s anti-Muslim colonial conquests, both at home and abroad.

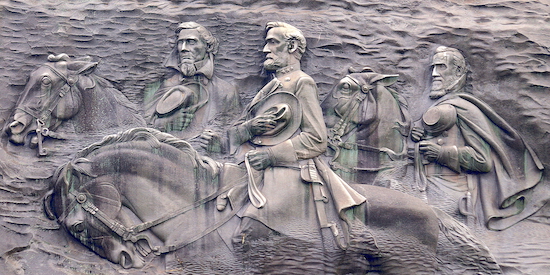

Where we grew up, white supremacist control of symbolic and institutional spaces has been asserted with particular daily persistence and visible force. We were born on the floor, so to speak, in the shadows of one of the world’s most grotesque monuments to white supremacy and most egregious acts of State-sanctioned vandalism: the Confederate Memorial Carving on Stone Mountain in Atlanta, Georgia.

In 1970 – in the midst of the Black Power movement, in a predominantly Black city and only two years after Atlanta’s Martin Luther King, Jr. was murdered – the state of Georgia unveiled a high relief sculpture, the largest in the world, of three of the highest-ranking slave-holding Confederates in the Civil War: Jefferson Davis, Robert E. Lee and "Stonewall" Jackson. It was here on Thanksgiving Eve 55 years earlier – ten months after the cinema debut of The Birth of a Nation – where William Joseph Simmons staged the first cross burning in the United States, thus inaugurating a revival of the Ku Klux Klan, which had been less active since its campaigns of terror to destroy Black life and undermine institutional measures to promote Black emancipation during Reconstruction in the 1870s. Only forty years before this, the United States under Tennessean Andrew Jackson, helped complete the ethnic cleansing of the Cherokee Indigenous people from Georgia in 1838.

Fast-forward to Atlanta, June 2020, just three days after Rayshard Brooks became the fifteenth Black man killed by Georgia police in 2020 – there have been 48 officer-involved shooting investigations this year alone – and three months after three white men murdered Ahmaud Arbery near Savannah, Georgia. The newly-elected Governor of Georgia, Brian Kemp – a Trump Conservative who once ran an ad, shotgun in hand, declaring his right to protect himself from undocumented workers, and who oversaw, as Secretary of State, his own election victory through widespread allegations of voter fraud – passed a law prohibiting Confederate markers from being moved anywhere but to a site of "similar prominence." This includes a 1907 statue of KKK criminal John Gordon Brown in front of the State Capitol in Atlanta and a 1908 "Lost Cause" monolith celebrating the Confederacy in Decatur, where I was born.

In the intervening years between 1870 and 2020, history has repeated itself in the South with such tragic, violent and farcical consistency it would make Marx shudder in disbelief. Vast economic and legal systems in the form of sharecropping and Jim Crow were constructed to impose a system of Black indentured servitude and mass incarceration. Voter suppression campaigns, poll taxes, voter Identification laws – all banned by the Civil Rights Act – limited Black political freedoms.

Segregation, the legal means to control, dominate and limit every aspect of Black life, remained in statute and enforced by police or lynch mobs long after it was outlawed in 1954. Meanwhile, the police and the KKK lynched over 3,446 Black citizens and activists alike in a reign of terror that spanned nearly one hundred years. The media did their part, helping create an image of Black criminality on the nightly news and pioneering the racist dog-whistle concepts of "looting," "riots" and "outside agitators" to undermine the Civil Rights Movement.

Throughout all this, white supremacist monuments, symbols, flags, and memorials have remained untouched or re-adorned as a direct response to Black struggles for emancipation. The Stone Mountain monstrosity, for example, was only completed in 1970. The purpose of this remains clear. "This monument and similar ones also were created to intimidate African-Americans and limit their full participation in the social and political life of their communities," reads a plaque near the Lost Cause monument. "It fostered a culture of segregation by implying that public spaces and public memory belonged to whites."

To say all this is not, however, simply to focus on the most visible, the most violent manifestations of white supremacy. As argued earlier, white supremacy – along with capitalism – is so insidious and entrenched because it is at once ideologically accepted as the norm and violently implemented at every level. All Americans, Britons and Europeans must think through how this manifests in their own history and contemporaneity.

American capitalism was built on slavery and the historical bloodlust persists today in the form of COVID-19 health inequalities, gentrification, mass incarceration, violent policing, colonial conquest, and worker impoverishment. There is, therefore, not an either/or choice between dismantling public symbols of control and pursuing the tangible demands to bring justice for victims; abolish the police; dismantle anti-black political, financial, health and education institutions; and end the miserable condition, in the words of Malcolm X, that exists for Black and other oppressed people on this Earth. It must all be undertaken at once.

As the great Southerner Angela Davis said recently, "These assaults on statues represent an attempt to begin to think through what we have to do to bring down institutions and re-envision them, reorganise them, and create new institutions that can attend to the needs of all people."