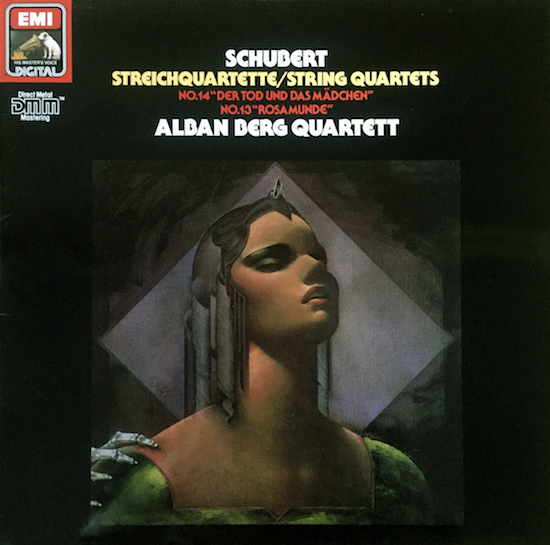

Put yourself in the offices of the German wing of EMI records in 1985. A leading group, the Alban Berg Quartett – named after the famous modernist composer from their home country of Austria – has just filed their startling new recordings of two disturbing Schubert string quartets and you’re on the hunt for a cover image to suit the album. You give an illustrator called William Beurge a call and suggest he depicts the better-known of the two pieces, Der Tod Und Das Mädchen (Death And The Maiden), written in 1824. He comes up with something that’s a bit Pre-Raphaelite, and also voguishly dystopian. The maiden looks upwards, eyes closed. Death is represented by the skeletal, metallic-looking fingers resting on her right shoulder. Creepy, isn’t it?

And now, very quickly, a boring story: a couple of years ago, a friend and newcomer to classical music, like me, came round to eat. Noticing a box of records, he said in mock pomposity: “Ah, Beethoven, shall we try the 7th or the 3rd?” He meant the symphonies, and I thought: “Why do we so often think of symphonies first when we think of classical music?”

We don’t always – for many, classical music means opera, or ballet, and some of the most popular pieces in the repertoire are piano and violin concertos. But they’re all large-scale, orchestral works, and if you’re coming to classical music from a rock/pop background, they may not be the best place to start. We know bands; we know what it’s like to hear a group of, say, four musicians play together and what’s possible when they do – great things. To jump from that to trying to wrap your ears around an orchestra isn’t exactly easy and that’s why this second Junk Shop Classical column is about two string quartets.

But don’t get me wrong here: just because string quartets are employed for decorative reasons in the wedding scenes of countless Hollywood movies, and at actual weddings, there’s nothing to say that music written for four instruments is lighter, or less probing, than an orchestral work. In fact, since Haydn developed the form in the 1750s, composers have often turned to the string quartet – nearly always two violins, a viola and cello – to make their most emotional and philosophical statements. It’s as critic Bernard Jacobson writes in the liner notes to a 1984 Alban Berg Quartett boxset of Beethoven’s late string quartets: “They’re most naturally suited to the activity of ‘logical disputation’ or ‘inquiry into truth’… Given four parts to play with, a composer working in anything like the classical key system has enough to fashion a full argument, but none spare for padding… The writer must concentrate on the bones of musical logic.”

Put another way, they can be very lean and very mean, and it’s no surprise that when Schubert realised in 1823 that he was ill with syphilis – not only a social stigma but a death sentence at the time that would indeed kill him five years later, aged just 31 – one form he turned to was the string quartet, writing the two chilling, minor-key pieces that we’ll get to in a second.

In the spirit of music journalists grossly over-simplifying enormous periods of very complex history, here’s where Schubert fits in the run, by birth date, of the Big Guns of Broadly Germanic Music: Bach > Haydn > Mozart > Beethoven > Schubert > Mendelssohn > Schumann > Liszt > Wagner > Bruckner > Brahms > Mahler > Strauss > Schoenberg > Weill > Kraftwerk. I’m not kidding about sticking Kraftwerk on the end there (they make a fun nod to music history with the song ‘Franz Schubert’ on Trans-Europe Express) and a similar run of the major players in Italian, French and Russian music would look just as impressive.

Schubert was born a parish schoolmaster’s son in Vienna in 1797 and grew up in humble circumstances to reach the inconsiderable height of 4’11”. He was chubby, too, wore thick glasses and was nicknamed ‘Schwammerl’ (‘Little Mushroom’) by his friends. In his lifetime, he was largely unknown outside of Vienna and constantly struggled to make a living. Unlike Mozart (who died young in Vienna before Schubert was born) and Beethoven (older than Schubert but living in Vienna at the same time), he had no rich patrons. And without an audience, swathes of his work were either written to make easy money – selling songs, not unlike a Tin Pan Alley songwriter in later decades – or to please his friends, a close-knit, sometimes-wild group of bohemians and intellectuals brave enough to think freely in a Vienna then ruled by an oppressive regime and secret police.

What makes Schubert exceptional is the sheer, absurd amount of music he wrote and its extraordinary quality – some thousand works in 17 years, comprised of over 600 Lieder (art songs, for which he’s best-known), nine symphonies (two uncompleted), masses, piano pieces, opera overtures and small-scale chamber works. To put that in perspective, if Beethoven had died when he was 31, he would have left a single symphony and a sprinkling of piano sonatas; Verdi just one opera of note, Nabucco.

Schubert was a torchbearer at Beethoven’s funeral in 1827 (only a year before his own death), but the sources on whether they actually met are shaky and that’s a constant issue with this most mysterious of composers; of all the greats listed above, he’s the one we can be least sure about (his illness is assumed, not proven) and that’s affected how we think about him today, and romanticise him. He’s a true cult figure in the history of classical music and, since he died, he’s been chucked around from pillar to post – dismissed by some for composing music that was considered “feminine” (after Schumann wrote about it as such, but only in comparison to Beethoven); claimed, when appropriate, by Austrian nationalists, but also by German ones, too; and he’s had his sexuality continually discussed, leading a music biographer, Maynard Solomon, to sensationally out him in 1989 (a claim subsequently questioned, and so it goes on).

Who was he? In a chapter in his book Listen To This, New Yorker critic Alex Ross has a go at defining his character: “He was friendly, up to a point; rude, when pressed; very shy or very arrogant, or probably both at once. He was colossally ambitious. He made a career and religion of music; he was a voracious reader who constantly tested the musical capabilities of texts. He could not grovel in front of potential patrons, yet he worked tolerably hard at self-promotion. His leisure hours were often drunkenly aimless. He formed intense friendships with men; he worshipped women but from afar. He theorised love more than he experienced it. He was prone both to euphoria and to paralysing melancholy, but he steadied himself with work. He was more a watcher of life than a participant in it: he had little time for anything unrelated to his art. There were no limits whatsoever to his musical imagination.”

It became fashionable in the 20th century to think of Schubert of having something of a split personality – a joyful and romantic sort with a brutally dark side – and that’s unquestionably backed up by the tunes, and one scrap of hard evidence in particular. Long after Schubert died, a childhood friend called Joseph Kenner made this remarkable statement: “His body, strong as it was, succumbed to the cleavage in his souls, as I would put it, of which one pressed heaven-wards and the other bathed in slime. Anyone who knew Schubert knows how he was made of two natures, foreign to each other; how powerful the craving for pleasure dragged his soul down to the slough of moral degradation.”

Did his bleaker side emerge after he contracted syphilis, most likely from a prostitute, or was it already there? That’s harder to define, but it’s after he got ill that he began to write his most crushing works. His Piano Sonata In A Minor from 1823 – a year in which he was hospitalised and flat broke – is almost unbearably tragic. (“It feels like your hands are turning to ice when you play it,” Radio 3’s Tom Service said in a recent broadcast about Schubert’s dark side. “It’s a musical gallows that this music traces in the air.”) Then, in 1824, just as Beethoven was signing off his epic ninth symphony for its May premiere, he wrote the Rosamunde quartet and Death And The Maiden – his 13th and 14th string quartets, and the two that are played so dramatically on this brilliant record by the Alban Berg Quartett.

We do have a significant clue to Schubert’s state of mind when he was composing these two pieces. In March 1824, he wrote to his friend, the artist Leopold Kupelwieser: “I feel myself the most unhappy and wretched creature in the world. Imagine a man whose health will never be right again and who, in sheer despair, just makes things worse and worse instead of better. Imagine a man, I say, whose most brilliant hopes have perished; to whom the happiness of love and friendship have nothing to offer but pain at best; whose enthusiasm, at least of the stimulating kind, for all things beautiful threatens to disappear and I ask you, ‘Is he not a miserable unhappy being?’”

Both Death And The Maiden and the Rosamunde are classic four-movement string quartets with the slow movement coming second. And, in both examples, the slow movements are built upon previous music Schubert had written – a 1817 song called ‘Death And The Maiden’ (itself based on a poem by Matthias Claudius of the same name) and incidental music he’d composed the year before for a play called Rosamunde, Princes Of Cyprus by Helmina von Chézy.

But they have different characters: Death And The Maiden is monumental, the Rosamunde more brooding; the former beginning with a slash of terror as all four bows slice across the strings in unison, the latter with a ghostly theme that was used to devastating effect in <a href="http://www.bbc.co.uk/iplayer/episode/b00920zh/storyville-dance-with-a-serial-killer"

target="out">Dance With A Serial Killer, a disturbing 2008 documentary about a French detective’s pursuit of the so-called ‘Criminal Backpacker’, multi-murderer Francis Heaulme. The film’s producers picked this exact recording of the Rosamunde, and that’s barely surprising – on this album, and many others (especially the Beethoven late string quartets mentioned earlier), the Alban Berg Quartett play with a sharpness that’s so lethal they occasionally sound vicious. But they couple their precision with a phenomenal clarity of purpose and deep empathy with the music.

The final movement of Death And The Maiden is a tarantella – a fast, Italian dance often interpreted to be Schubert’s dance of death, or an attempt to ward off madness. And it’s there, in that fury and chaos, that you truly sense his pain – his battle with illness, and the inevitability of his demise. But there was so much more incredible music that Schubert would go on to write before passing away four years later, especially his sublimely melancholy song cycle Winterreise (Winter Journey).

We’ll leave that to a future column and finish this one with a note for travellers: If you ever find yourself in Vienna, save half a day to get out to the Central Cemetery – Zentralfriedhof – on the outskirts of the city, a vast and beautiful place. There, in one small circle, around a cenotaph honouring Mozart, are the final resting places of Beethoven, Schubert, Johann ‘The Waltz King’ Strauss II and Brahms. Nearby, Schoenberg and the brilliant Hungarian composer György Ligeti are buried, complete with stunning, modernist gravestones. Find a bench and begin reading, as everyone should in Vienna, Graham Green’s The Third Man as. The action starts right there in the cemetery!