We’re never going to get anywhere unless we have some common ground, and the common ground is this: The Beatles are the greatest, most important group in pop history. It doesn’t matter if you don’t like The Beatles. It doesn’t matter if you disdain any music made for the specific purpose of encouraging as many people as possible to enjoy it. It doesn’t matter if, say, Nurse With Wound are far more important to you than all other groups, The Beatles are still the greatest, most important group in pop history.

First, because more people have bought music by the Beatles than by anyone else ever (and, yes, it does matter. Popularity on that scale is different to Joe Dolce keeping Ultravox from reaching No 1. Popularity on that scale is proof that you are loved more than anyone else who ever made a record, and you have to be great to be loved that hard for that long).

Second, because if The Beatles didn’t do everything first and didn’t do everything best, they did some things first and they did some things best, and they did a lot of other things nearly first and and nearly best. Who else can say that? Prince, maybe? Miles Davis? (Probably, but he’s not a pop artist, so he doesn’t count.) Third, because uniquely among the major artists of the rock era, The Beatles’s meaning is mutable. They can mean everything to everybody.

You might think that the longer an artist works, the easier it is to ascribe different meanings to the periods of their work. I’m not at all sure that’s true. In fact, I suspect it’s the very concision of The Beatles’ career – and the insane productivity and development they crammed into it – that means their meaning can be altered.

They released 12 studio albums in a shade over seven years, a catalogue both so popular and so contained that almost everybody with a passing interest in pop is familiar with most of it. You might have been put off by Let It Be‘s poor reputation and given it a miss, but even so, you almost certainly know the title track, ‘The Long And Winding Road’ and ‘Get Back’. If you have no taste for vigorous rock & roll, you’ve perhaps not bothered with the first four albums, but you still know good chunks of them, because it’s almost impossible not to.

The Beatles career divides neatly into three periods – early Beatles (the four albums from Please Please Me to Beatles for Sale), middle Beatles (the four albums from Help! to Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band), and late Beatles (the final four albums, from The White Album to Let It Be) – almost as if they were making themselves into three different groups, each of whom could be considered differently. It’s not as though no one else has ever had careers in which they have transformed themselves across time – of course they have – but none of have them done so in such a short time, such a contained manner.

Take Bob Dylan. His career is so long, so ever-changing that it becomes incomprehensible to anyone bar the committed; no one in their right mind wants to be trapped in a pub with the person who has an opinion about every Bob Dylan album. [This is the first bit of this feature I’ve agreed with, Ed]

The Stones’ career has dragged on so long, generating so many terrible albums over such a long time – what was the most recent Stones album you listened to in its entirety purely through choice? For me it’s Tattoo You – that they have allowed themselves to be calcified instead as one single thing: The Greatest Rock & Roll Band In The World, which in practice has meant spending the last few decades selling themselves as a reanimated version of 1971 (is there anyone under 75 who, if asked to describe the Stones, would call them a blues band? Wouldn’t everyone refer to them in terms of that period from Beggars Banquet to Exile on Main Street? That’s surely what the Stones mean in the wider culture).

Even with my beloved Springsteen, I couldn’t argue against the idea he’s defined by his first seven albums, and in the wider public mind probably just by the five from Born To Run to Born In The USA, even if I think he’s made great music since then. By and large, I suspect, public interest in an artist as a creator of new work usually (but not always) lasts about a decade, which is a happy coincidence given that artists usually (but not always) have just one rock-solid, A-grade decade in them. The Beatles didn’t even manage that decade. Just 12 albums, split into three periods, in a little more than seven years. Everyone can know them, and everyone can have an informed opinion about them. And because of that, their legacy is unusually open to debate; their meaning is mutable. Which is why each era has its own greatest Beatles album.

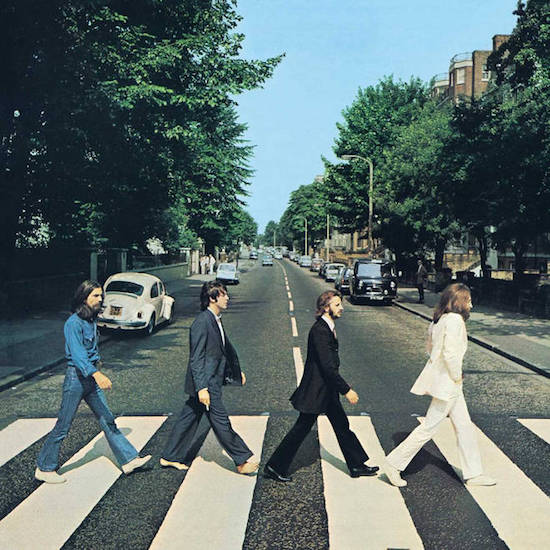

This week is the 50th anniversary of Abbey Road, and this week Abbey Road is the greatest Beatles album of all. On BestEverAlbums.com, which aggregates all the magazine lists and allows users to submit their own rankings, it is rated as the third best album of all time, and the best Beatles record of all. It’s not as though any era of the The Beatles is ever wholly ignored (though the early records are less venerated), but the relative status of particular LPs rises and falls with the times. At the moment, we’re living in a bull market for late Beatles, with Abbey Road and The White Album the beneficiaries. When Pitchfork compiled its 200 best albums of the 1960s two years ago, the highest ranked Beatles album was The White Album, at No 4. Abbey Road was No 16, and between them – at No 8 – was Revolver.

For many years, Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band was the undisputed champ. Not just the best Beatles album, but the best album of all time: No 1 in NME‘s 1974 all-time list (The White Album was No 39; Abbey Road didn’t make the list). Sgt. Pepper was the boomers’ Beatles album, the one that defined their moment of cultural apotheosis. You know the spiel: how the morning it was released, it was playing out of every single window on every single street; how literally no piece of music ever had been as daring, or contained such lyrical profundity, as ‘A Day In The Life’; how it defined a generation. As long as the boomers controlled the world, its status was more or less secure. And in 1987, when the Beatles’ catalogue was released on CD for the first time, only Sgt. Pepper got anything other than the standard jewel case (it duly went back into the UK album charts, reaching No 3). But there were signs of a challenge. When the 1985 crop of NME writers compiled their own greatest ever albums list, one shaped by punk and post punk, Sgt. Pepperwas banished entirely: the highest Beatles-related record was John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band at No 9; the highest actual Beatles record was Revolver at No 11.

Change came, in the UK at least, in the 1990s, thanks to the combination of a book and a new pop movement. Ian MacDonald’s Revolution In The Head – a collection of short historical essays and bold appraisals of every single Beatles song – displayed an enormous enthusiasm for Revolver-era Beatles, while taking a more sceptical approach to Sgt. Pepper and to much of the later Beatles. That coincided with Britpop, and suddenly 1966 Beatles was the only game in town. It’s not just down to Oasis (whose own musical fondness for later-era Beatles, with their terraces-meet-cult-gathering choruses was evident from early on), but to what Revolver represented: urban, youthful, experimental but accessible, artsy but still rocking, and filled to the gills with really good drugs – to the exent that the Chemical Brothers and Noel Gallager simply remade ‘Tomorrow Never Knows’ as ‘Setting Sun’. Revolver became the new orthodoxy, and when NME yet again catalogued history in 2003, it was the top Beatles album (No 5), as it was in Mojo‘s 1995 list (No 3) and Q‘s 2006 list (No 4). It was VH1’s greatest of all time in 2001; Virgin’s No 1 in 2000; The Guardian‘s second greatest in 1997. Five years ago, Revolver was the highest ranked Beatles record on BestEverAlbums.com. Only, it seemed, Rolling Stone – where publisher Jann Wenner perpetuated the boomer supremacy long after it seemed sensible – continued to fly the flag for Sgt. Pepper.

But now the age of late Beatles is upon us. Why? Late Beatles is music for our age. Melancholic but uplifiting anthems have an enduring power that a lot of people find irresistible: Coldplay, at heart, are a synthesis of late Beatles elements. But there’s more to it than that. If this is the age of musical atomisation, as we are often told, when streaming allows every person to pursue every taste, then late Beatles – in all its insane variety – allows people to pursue those tastes. That’s the charitable interpretation. The less charitable one might be that in an age of continual self-indulgence, in which everything is an Instagram opportunity, where no microtaste is too specialist to be indulged, in which artists are celebrated for wallowing in their own lack of discipline – go on, make your album longer: two hours! Three hours! Don’t bother with tunes! Slap down anything that comes into your head! – then late Beatles is the perfect exemplar of that.

The things that are celebrated about Abbey Road today are the things that most embody modern attitudes. The “long medley” on side two seems now to be regarded as an unparalleled masterpiece: “A song cycle bursting with light and optimism, and this glorious stretch of music seems to singlehandedly do away with the bad vibes that had accumulated over the previous two years,” said Pitchfork of the 2009 reissue. Alternatively: here’s a load of scraps The Beatles couldn’t be bothered to work into proper songs, but they still needed to fill up an album, so here you go. Abbey Road has not one but two novelty songs, one of which (‘Maxwell’s Silver Hammer’) none of the band even liked. It has the interminable ‘I Want You (She’s So Heavy)’. And it has 16 minutes of unfinished songs. And that’s the greatest?

But there’s another reason for its current status, which is that it’s actually the Beatles album that remains most current in circulation. On US radio, the older Beatles material is now too old; it doesn’t fit any formats. But Abbey Road does: ‘Come Together’ is still a staple on classic rock radio (as is Aerosmith’s cover); ‘Here Comes the Sun’ can still be rolled out every summer. And those are the two most popular Beatles songs on Spotify, with ‘Here Comes The Sun’ way out in front of anything else. There’s a generation to whom these songs are the most common manifestation of The Beatles. Never underestimate the effects of having something shoved down your throat repeatedly to make you like it best.

But I’m being harsh, because I like Abbey Road. Even if it is the only Beatles album on which George’s songs are clearly and unquestionably the best. Even if it demonstrates the ironclad rule that no group that started with short hair ever got better with long hair. Even if it has caused traffic chaos in north west London for decades. I like it. But the greatest ever? That says more about the world than it does about The Beatles.