We’re only too aware of The Special Relationship in Britain, a Churchillian phrase in origin intimating close ties between the UK and the US which gets trotted out whenever Allied forces scramble for fossil fuels and bloodlet under ostensible acts of humanitarianism. It’s a delusional bond between two nations that nobody outside of the political classes takes much notice of in real life, and never in the USA, where they fail to reciprocate almost entirely. Americans have their own special relationship to think about, not with a country but with a city not a million miles away from London, a habitat just over the channel from us that they appear transfixed by and hopelessly devoted to. Or at least the idea of it anyway.

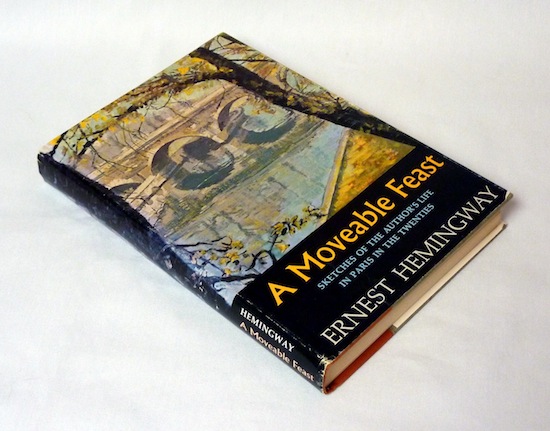

"J’ai deux amours," sang Josephine Baker, "mon pays et Paris" (I have two loves, my country and Paris), and the late, great Josephine is by no means alone in her infatuation; Americans in creative industries have been paying homage to the city since the roaring twenties in song, in movies, on television and in books… from Hemingway’s A Moveable Feast to Woody Allen’s Midnight In Paris, two of the more obvious examples. The latter is of course deliberately beholden to the former, though intriguingly one wonders whether the Paris that has been disseminated throughout the world by Hollywood ever since Les Années folles, is more a simulacrum of the city as it was then, than anything it truly represents in the present. Post Haussmann, Paris may well be better at preserving in aspic it’s art nouveau / art deco facade than other cities (who can only look on jealously and rue shortsighted cultural vandalism) but many of the freedoms it supposedly represents to America – and thenceforth the rest of the world – are no more or less free or utopian than any decent-sized metropolitan, occidental city in this age of globalised conformity.

As a regular gig attendee I see fair amounts of artists passing through my adopted city, and it’s the Americans who are always the most enthusiastic visitors (you could argue that Americans are more enthusiastic by their very nature than most – which might be true – but I think it runs much deeper than that). When Lana Del Rey played L’Olympia last year she was overwhelmed to be on "such an iconic stage in such an iconic city" with a history that had seen the likes of Edith Piaf appear there, and she performed Cole Porter’s ‘I Love Paris’ to further prove her devotion, should her between song gushing not serve as testament enough. Sparks’ excellent turn at the Alhambra saw Russell Mael express his passion for Paris without reserve (the band have recorded songs ‘The Louvre’ sung in French, and ‘Sextown USA’ – which name checks seedy Pigalle), and the extended bow at the conclusion that became painful in its protractedness felt very much like it was being proffered to this city alone, by unabashed Francophiles.

Paris is supposedly the most photographed city in the world, and it’s one of the most sung about too: Tom Waits, Louis Armstrong, John Denver, Dr Hook, Rufus Wainwright, Quincy Jones, Connie Francis, Elliott Smith, Debbie Harry, Sufjan Stevens, etc, etc, have all recorded songs about Paris, while this romantic hotbed of culture has captivated musicians from Miles Davis to Kanye West, who both had/have a special affinity with an urban dwelling that symbolises freedom and creativity, liberal values and acceptance, bohemianism and debauchery. Whether or not 21st century Paris offers any of those things in measures more abundant than any other creative hub you might care to mention is open to question. As for the nexus which binds these disparate progenies separated by three and a half thousand miles of water? Well, that goes back nearly two and a half centuries.

Some historians cite 1776 – when thousands of Frenchmen volunteered with the Marquis de Lafayette to fight in the American War of Independence against the British – as the moment the love affair began. The Statue of Liberty, a gift to New York from the people of France in 1886, was an affirmation of this love. It was (and still is) inscribed with the American Declaration of Independence and the date July 4th, 1776, should anyone be allowed to forget. For a nation as young as America, these historical ties are binding.

The real love-in began in earnest not long before the gift had been dispatched across the water, roughly lasting the duration of the Third Republic – from about 1870 to the outbreak of the Second World War, taking in la Belle Époque and most significantly the 1920s. Even after the Nazis invaded Poland in 1939, around five thousand US citizens ignored the advice of American Ambassador William Bullitt (according to Charles Glass in his book Americans in Paris: Life and Death under Nazi Occupation 1940-1944) and stayed in the city, though in truth, the numbers had dwindled significantly post-Wall Street Crash in 1929. Before then there were believed to be as many as forty-thousand Americans living in the city, many of them still hanging around after the Great War, and many writers, artists, musicians, diplomats, journalists, socialites, financiers, philosophers, drifters etc, escaping the Volstead Act and prohibition back home in favour of pursuits bohémien in their favourite European city. Gertrude Stein called them the génération perdue.

In Alistair Horne’s Seven Ages Of Paris: Portrait Of A City, he notes that 5.3% of the population was made up of foreigners in 1921 – many of these Americans – with that figure almost doubling a decade later. This was boomtime for the expats.

"Oscar Wilde’s Mrs Allonby observes that when good Americans die they go to Paris," wrote Horne, "but after 1919 even not-so-good Americans took off in droves for Paris. For $80 they could secure a ship berth; otherwise they could work their way ‘shovelling out’ in the holds of cattle boats; and the modest allowance in dollars would maintain an American in Paris for an indefinite period." And so they kept coming: Archibald MacLeish, Dorothy Parker, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Isabella Duncan – the dancer who was tragically strangled when her scarf became entangled in a car door – and Sylvia Beach, founder of the bookshop Shakespeare and Co., which still resides in what they liked to call Odèonesa on La Rive Gauche.

The left bank, like the Manhattan of the 70s, was a hive of creative activity and a wellspring for adventures in original thought, and we all know what happened next. When Hemingway borrowed a book from Sylvia Beach in A Moveable Feast, he wrote: "She did not know me and the address I had given her, 74 rue Cardinal Lemoine, could not have been a poorer one," whereas now, some 90 years later, you’d be lucky to get a room on the same street for less than €1,300 a month (exclusive of bills and council tax), and bear in mind rents are comparatively cheaper in Paris than they are in London. What was once a vibrant community of creativity has become what some insultingly refer to as ‘Postcard Paris’, an area corrupted by real estate, crepe shops, coffee conglomerates and Irish bars dotted amongst the writer’s plaques, St Etienne du Mont and le Jardin du Luxembourg. Inevitably stiffs with no talent move in, in the hope that some of the genius might rub off, only to kill the place stone dead with all the other stiffs who had the same idea. You’ll find plenty of Americans still, but not necessarily scribbling short stories and drinking rum St James in cafes off the Place Saint Michel or admiring Cezannes at the Musee du Luxembourg. Many of the Americans you’ll find will be living up to the stereotypes of latter day US citizens on holiday, invariably in bad shorts, chugging on Starbucks or ordering everything on the menu in stridently defiant, deafening English.

It’s not just the Rive Gauche. The creative types have mostly moved out of the artistic enclave of Montmartre where Picasso turned up in 1900 and gradually made a name for himself; now it’s all overpriced drinks, students with guitars hanging around the Sacre Coeur, street sketchbook artists and men trying to hawk you a flashing Eiffel Tower keyring. The memories of Toulouse-Lautrec, Van Gogh and the Impressionists are still maintained here, mostly in racks of postcards in the many gift shops from the Place du Tertre down to the Anvers’ Metro. So where do we find these young vagabond geniuses wafting around in laudanum hazes or banging back absinthe? Unlike in New York, the artists haven’t necessarily ventured out beyond the peripherique or found somewhere cheaper en masse. According to artist Martin Lord, who has a studio at Point Ephémère – a venue in the 10th arrondissement that hosts artistic events – the sense of community that once thrived here is still in evidence, but it’s more fractured, divided between your average Art Fair acolyte and the more vibrant underground.

"There is still a dynamic art scene here, but the world doesn’t look at Paris as an art epicentre anymore," he says. "What I see is that there are a lot of artists here, a lot of different kinds of artists and different markets for the art. Some come here with a sense of nostalgia, some people come here to buy art from that same sense of nostalgia, but it’s just postcard stuff. The schools are very highly considered, there is a very dynamic and really interesting art scene here, but it’s very France-oriented; what we have to be aware of is that some stars of the contemporary art scene are stars, but just in Paris. We have to be modest about that."

He adds that Paris itself is "overrated". But in what way?

"The rents are high, so not everybody can afford it, and so not everybody wants to come to Paris. There are others cities that can be proud of real art scenes now: Lyon, Lille, Nantes… to name but a few."

Axelle Remeaud, another contemporary artist who recently exhibited at Point Ephémère, has a studio in Belleville, which she describes as "central and very lively, not too expensive, where there are many small galleries and nice bars." Just like in London, a lot of artists have moved east to take advantage of cheaper rents, only for those rents to increase when the postcode becomes vibrant with youthfulness and creativity – a catch 22 – though Belleville has some way to go before it turns into bobo Oberkampf just down the hill. Only a few years ago it was Bastille that became gentrified, and now there seem to be fewer and fewer places within the periph where a fledgling artist can struggle for a while before hopefully getting on their feet.

Mark Thompson, proprietor of gigsinparis.com and culture correspondent at France 24 doesn’t see it as some kind of artistsic diaspora, though. "It’s a constant chase, just as it is London, Berlin, New York… anywhere which breeds creativity really. For the moment it looks like the 20eme and 11eme [arrondissements] are the places to be but soon they too will become gentrified and expensive, but the 19th is already waiting in the wings to pick up the pieces. Let’s face it, there’s not that much money in art at a base level; the people who do it as their day to day jobs who aren’t expecting their work to be hung up in the Palais de Tokyo, I mean. Because of that they’ll go wherever the rent is cheap."

Beyond the periph seems to be a no-no, though.

"It’s a strange thing about Paris," says Martin. "In New York the artists are always going away from the high rent or the growing value of an area, because they have to afford a studio or an apartment. Here it’s not that easy to imagine the art scene moving [outside]."

What about squats – or "squarts" (a franglais portmanteau of the English words "squat" and "art")? Like La Miroiterie for instance, a renowned artists’ community for nearly a decade and a half up the hill at Ménilmontant, an abandoned mirror factory that was eventually closed down by the authorities. Are these communities becoming a thing of the past?

"Yes, I think increasingly, places underground will have to disappear because the city needs space," says Axelle. "It is a real pity."

Mark Thompson agrees: "There are actually a growing number of artist squats in the French capital, but most are feeling the impact of the local government in one way or another. They either receive funding and therefore lose some of their appeal or they get closed down. The city council will tell you that over 17,000 square metres has been given to artists around the city since 2001, but they’re forced to fullfill the city council’s quota."

What about 59 rue de Rivoli, which has a vibrant facade – and located where it is between Hotel de Ville and The Louvre, is right in the catchment area for tourists?

"Squat 59 Rivoli is the perfect example, as it was actually bought by the city twelve years ago to stop the artists squatting there from being evicted, but last year when their contract came up for renewal, the city threatened their independence by increasing the rent and reducing the number of permanent artists who could showcase their work in the space."

Things may not be all they seem, but then as Jonathan Meades puts it in his documentary In Search Of Bohemia, "perhaps all places are ideas to people who don’t live in them." Paris represents an idea rather than a reality more than most, though, a city that the world sees through Hollywood’s filter based on a time period nearly a century ago – and a place that has its own syndrome named after it. Paris Syndrome is a transient psychological disorder suffered mainly by Japanese tourists which apparently manifests from the divergence of the person’s idealised impression of Paris and the disappointment of the reality. The worldview of Paris disseminated from Hollywood and often shot in studios in California or New York rather than on location (see Sex And The City or, say, The Last Time I Saw Paris starring Elizabeth Taylor), is mostly a fallacy, a bit like The Special Relationship we were talking about earlier.

"To be fair, films made in Paris by French studios are alway using the city’s postcard representation too," says Martin Lord. "Most of the movies from Paris are not real life. There is always a beautiful apartment, they always go out on the Champs-Élysées or in St-Germain, they never work and everybody is an artist, actor or whatever. There are a lot of difficulties here, lots of people, a massive disparity between rich and poor, that is life. You’d think Paris was just St-Germain des Près and nothing around it, but it’s multifaceted and complex."

"Obviously the Paris portrayed in the media and in Hollywood is not the real Paris," admits Thompson, a British expat. "It’s less Amelie and more La Haine, but that doesn’t make it any less beautiful, you just need to have the right expectations."

"Maybe Hollywood likes to play up the glamorous side of Paris," says Axelle Remeaud, "and actually we live in a city quite different from Les Années folles. Things move on, but unfortunately not stereotypes."