Forewarning: The words ‘I’ and ‘my’ appear frequently in this article. You can either take that as being symptomatic of a period in which every listener’s musical future is apart and subjective, or you can bemoan the extreme arrogance of my assumption that everyone else thinks and operates as I do. I’ll leave it up to you.

When was the last time someone knocked on your front door and tried to sell you something? Not a new brand of electricity or charity, or a religious conversion, but a tactile, tangible, ruinable object; something claiming space and gravity from the universe you could see with your eyes and hold in your hands? I remember one such moment from my 90s childhood vividly – I answered the door to a man in a suit, and for the next half an hour that man tried valiantly to sell my mother and I a range of premium encyclopaedias; 26 in total, all bound in red leather, with a book handling all the problems each letter in the English alphabet had thus far managed to fling at the world.

It was a confusing, fantastic experience. For the totality of that half hour I was rapt by the man’s mania for these mysterious, red books and the arcane knowledge trapped within, the way that, through his patter, his persona swung violently between capitalist and librarian and by the mud on the tips and heels of his brogues (there was a hosepipe ban in place locally at the time). The man with the books in the suit and the brogues was an incredible apparition; his performance a lightning bolt in the glazed retina of a standardly tedious, suburban weekday.

We didn’t buy anything from him in the end, and he went next door, who I don’t imagine bought anything from him either. He was asking a fortune, and besides, the internet would arrive in our home five or six years later, financially vindicating our decision in the long-term. The idea that anyone would spend hundreds of pounds on a 26-volume encyclopaedia sold by a stranger on their doorstep seems absurd now – there’s all that and more to be found on the internet, obviously, but the death of the traveling salesman is nonetheless a sad one, and one that’s been ignored in the clamour to mourn the high street.

In that gap between the salesman and the home computer, I became conscious of music beyond that which was offered to me by my parents (Bowie, Idol, Dion) or the Sunday singles shelves of Wycombe Asda (PJ and Duncan, MN8, Sisqo) and bands started to appear in my life in much the same way that salesman had – violently and suddenly, like fleshy apparitions, with esoteric stories to tell and dirty shoes. New bands – and it almost invariably was bands, back then – would burst anew into my imagination from the covers and guts of magazines (At The Drive-In, The Icarus Line, The Distillers, Ikara Colt, The Strokes), the recesses of cable-fed music television (Sonic Youth, Outkast, Bloc Party), or the support bills for acts I already knew and liked enough to go to see live (ZSK, F-Minus, The Rakes). Then there were label compilations, (Epitaph’s ‘Punk-O-Rama’ series and, later, the Buddyhead samplers) as well as CD-Rs burnt by likeminded school friends (Rancid, …Trail of Dead) and the blessed ‘sales’ racks at my local MVC that I’d pore over post-Burger King shift (Joy Division, Fugazi, The Stooges, My Bloody Valentine, Roxy Music, Miles Davis, Lou Reed).

My taste in music was so typically pubescent at that point that really someone should have wrapped a condom around my tongue, but the point is there were surprises – bands would appear in my world without invitation, or, if I did invite them in (by buying their records or tickets to their shows), it was often before I’d heard a single note of their music.

This approach now seems as absurd as the idea of handing over £700 for those books. I chase most of the music I listen to now myself – when was the last time you fell in love with a new band after hearing about them in the music press (the internet doesn’t count: it’s always active, there are no breaks in play, no ‘apparitions’)? Or the last time you fell in love with a band after wandering a while and just dropping randomly from street-level into the rumbling dark of an underground bar? When was the last time you went to a show without knowing what the bands – main act AND support – sounded like in advance?

There are no more traveling salesmen in music. It’s not just the abrupt transpiration from nowhere that’s missing – it’s more literal than that, more specifically in terms of that word ‘traveling’. <a href=Whttp://thequietus.com/articles/01594-the-horrors-daub-their-name-in-british-pop-tradition-with-radiant-primary-colours" target="blank">I’ve talked for too long before on the disappearance of Michael Bracewell’s ‘suburban dandy’ – that breed of pop musician grown in small-town boredom, who flees with their ideas to the city in order to find the people and the means with which to transform that boredom, and those ideas, into excitement and renown. Pop musicians like The Cure, The Clash, The Pet Shop Boys, David Bowie. Less and less does London feel the physical presence of young, tribal, modish pop peacocks pounding its streets from one music industry outpost to the next – from rehearsal space to studio, studio to bar, bar to board room, board room to photo shoot, photo shoot to live stage, live stage to Top Of The Pops. The internet has destroyed that need to rap knuckles on the city’s front door in order to gain its attention.

It has destroyed the need to get out of bed, even; or at least to leave a bedroom hunkered in some tedious, local, provincial vicinity. The bedroom shrinks most of the music industry to the size of something you can fit under or on top of your desk. You can record, rehearse, produce and distribute your own music on a home computer with cheap software and an internet connection, you can talk all day to the people putting your record out on Gmail chat, you can find critical response and – most importantly, perhaps – an audience on ‘blogs, sites like the Quietus, forums and MySpace. If you trace your finger from one end of the decade to the other, the most vital musical mutation in the last ten years has taken place in the room where you spend six to eight hours a day unconscious.

People talk about the way the internet has ‘democratised’ music in the last ten years. That’s a load of shit, really – as John Tatlock’s excellent recent article on ‘Myths Of The Digital, Post-Napster Age’ demonstrated, industry-backed gigantors like U2 and The Spice Girls are still hogging the slop trough, financially at least. People talk a lot about what the internet’s done for music, but not so much has been said yet on what it’s done to it. Rather than talk about a commercial democracy, it’d be more apt – and more interesting, for me at least – to talk about a constellation of stylistic bedroom dictatorships. A recording artist working alone will not invariably become an auteur, but it certainly seems to have helped – as the internet continues to isolate people within their own, disparate physical realities, so lonely solo artists seem to respond with songs and tracks borne from a more personal, less gregarious place; closer to true visceral, gut feeling. Away from scene pressure, artists are free to indulge their imaginations – get lost in their own worlds – and ditch etiquette and ‘contemporaries’ for the development of subjective method and (a) signature sound. There may not be any more auteurs than there were in 1995. It could just be that the internet has made it easier for the bedroom-bound auteur and listener to find each other. One might argue, though, that when your bedroom project is just one among a huge, vast fucking many, logic and instinct will urge you to develop a sound that sets you apart from the din of the mob.

Nonetheless, the isolation and comfort intrinsic to bedroom production seems to have created a particular mood that aches through the pores of much of this year’s most affecting and cherished music, inconsiderate of notions of genre, influence and target audience – a mood that’s appropriately private, warm, tender and hypnagogic for sounds coaxed forth among your socks, sex, and rapidly evaporating night-dreams.

Toro Y Moi – ‘Sad Sams’

Washed Out – ‘Get Up’

Future Trends – ‘Moonraker’

Memory Tapes – ‘Bicycle’

Memory Tapes, Toro Y Moi, Washed Out and Future Trends all have signature styles, but all are responsible for some of that private, warm, hypnagogic music. They’re also four of the most notable actors in a scene no-one has a name for yet. The name I’m going with, for the sake of ease and this essay, is ‘glo-fi’ – for its connotations with warmth and radiance and its proximity to ‘lo-fi’, it seems a better fit than ‘chillwave’, an alternative name found hanging in the weed burps of rad ‘net dudes that won’t stink us out for too long. ‘Dream-pop’ has also been suggested, and is probably a more valid term than the latter, given the sound’s bedroom-genesis and the way those aforementioned acts all conjure a hazy, addled synthpop that, broadly speaking, trades an 80s future for an 80s past; mind’s eye projections of bold, sharp, questing angles exchanged for the soft-focus, slow-exposure Impressionism of reconstructed memory.

It’s probably important at this point to give shout-outs to those other vital, loose, invariably un- or semi-named bedroom-produced pockets pushing out artists using Impressionist memory to create new, signature sounds – to the flannel-shirted lo-fi punk of Blank Dogs, Cloud Nothings and Graffiti Island; the house-kraut head dances of Teengirl Fantasy and Blondes; the silver-veined, red-eyed ‘future garage’ of UK producers Joy Orbison and Sully and New Yorker FaltyDL. All offer favourable ratios of great, but they’ll be abandoned at this point in the essay because ‘glo-fi’ seems to engage with the internet’s potent combination of loneliness and new technology in a way that no other area has desired or managed to yet.

For one, the music just sounds better played through laptop speakers. I realise that this is intolerably subjective, but listen to Washed Out’s ‘Feel It All Around’ (below) with your external speaker system unplugged. It just makes sense. Whether that’s because Washed Out – and Toro Y Moi, Memory Tapes, Future Trends and countless ‘glo-fi’ others – grew up in the 80s and therefore need their technology to sound like it’s on the verge of dying, I don’t know. It could just be that all the pleasure tones are concentrated at the high-freq, trebley end of the mix (in those sighs that leak and spray over you like something between gas and liquid bliss). Certainly sub-bass doesn’t play too big a part – what bass there is tends to be of the sinewy, slapped kind beloved of whiteboy MOR radio funk. It’s as if Washed Out (U.K.A. Ernest Greene) and Toro Y Moi (U.K.A. Chaz Bundick) in particular have produced their music with the limits of bandwidth and laptop speakers (as well as the latter’s mobility) in mind. Following the disastrous (or at the very least uncomfortable) jump from MySpace to the live stage many blog-hype bands have endured in recent years (Wavves and Telepathe immediately spring to mind) it shouldn’t seem too ludicrous to think that Ernest and Chaz have recognised the fact that some music just sounds better on the internet.

Other signs that the ‘glo-fi’ cadre suit the internet better than most others can be found in the details of their CVs. Greene’s an avid photographer, while Bundick’s ‘blog shows off both his photography and his degree in graphic design. The man behind Future Trends, one Andrew G Clark, is currently in his senior year also studying graphic design, at the school of advertising art in Dayton, Ohio (his ‘blog’s here).

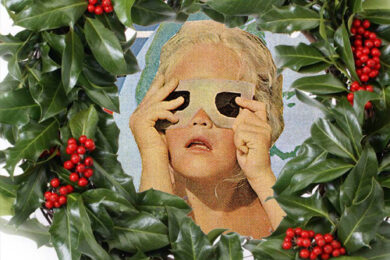

Memory Tapes, meanwhile, is a stay at home dad (Dayve Hawk) who can’t drive, suffers from social anxiety, doesn’t own a mobile phone and remained anonymous for about a year while all were a-froth with love for him and the music he was making as both ‘Memory Cassette’ and ‘Weird Tapes’. I guess he’s where the loneliness part comes in, hard ("If it were up to him," remarked a rather prescient scribe when writing about Hawk’s former band Hail Social for the Philadelphia City Paper, “he would ship his songs from his bedroom to the world.”) But while not trained or busy himself in the field of visual arts, he nonetheless acknowledges the debt he owes to his artist friends (“I have had good luck with generous artists”) and by removing his face, it was the two images below that people came to associate with Hawk’s music.

It’s difficult to overstate the importance of these visual factors. Most immediately, the photographs, collages and graphics Washed Out and co. surround themselves with are often as articulate of that yearned-for, wordless nostalgia their music luxuriates in as the music itself. They back each other up, the music and the photographs, accumulated evidence for the kind of hopeless wistfulness that prevents ‘glo-fi’ being a mere re-run of future-besotted 80s synthpop. The use of photography and graphic design in MySpace and on ‘blogs, in videos and virtual record ‘sleeves’ shows an understanding of the possibilities of endowing your music a visual, temporal and emotional context that would traditionally be imposed upon it later by a journalist. This way, you can provide hacks and ‘bloggers visual cues as well as audio ones, manipulate them softly into thinking of your music as something to soundtrack summer evenings spent warm and wet by lagoons, or cinematically epic house parties in young, suburban America or that moment when you’ve let go of the swinging, blue rope and your body hangs poised between the sky and its reflection on the surface of the water (images courtesy of Washed Out and Toro Y Moi).

When you consider that video above for Washed Out’s ‘Feel It All Around’ is fan-made, you can see that visual cues can be a great help if you’re an artist who spends too much time alone, trying to take something from your achey gut and put it straight into music undiluted by bandmate ignorance, scenester etiquette and the distractions of the outside world. Greene’s gut pangs have clearly transmitted: the fan-made video features water, summer, travel, youth, friendship; the key components of Washed Out’s nostalgic image – even if that travel often seems the subject of ‘glo-fi’ nostalgia, as if going outside into the world was something consigned to the past to be recalled now fondly; a nostalgia targeted expertly by over-lacquered, super-resolution travel brochures.

The way ‘glo-fi’ artists use visuals is also important in terms of the way I, and many others I know, now consume new music. When I talked earlier about chasing new music down myself rather than it finding me, I had in mind the process of ‘MySpace Wandering’ – the natural way in which, having found a new, favourite artist, you then check out the other artists listed in the ‘Top Friends’ section of their MySpace page. It was this method that led me to Washed Out, when I scrolled down and found him in Toro Y Moi’s ‘Top Friends’. He presented himself and his music well, with the need for nothing other than a hazy, weather-beaten polaroid to snare the attention of the nostalgic, bedroom-bound parts of my mind. In the right, knowing hands – in hands practiced in photography and graphic design, for example – that ability to represent an own, signature sound in visuals becomes advertising. No – it is advertising; a remote exchange, a trap laid and left, like the images people put on television in an attempt to make more money for themselves. You don’t see the salesman, he is not at your door. He has resigned himself to waiting in an undergrowth of technology for you and your attention span.

One curious trend in TV advertising that seemed to develop as the decade wore on was the keenness of advertisers to co-opt and exist within the ‘realm of the real’. Ten years on from the man with the books in the suit and the brogues, we’re back in yet another (the same?) standardly tedious, suburban weekday, except now it’s ‘real’ people on a screen trying to sell me stuff – the salesman, once an unpredicted, unpredictable bolt from the blue of a life on the road, has been trapped behind a glass screen and reduced to padding along in an endlessly repetitive existence of cruel, unparalleled drudgery; i.e. ‘reality’. He can’t be ‘real’, though, because advertisers have trapped him in an ossified, glass-cage version of ‘reality’ that’s pre-recorded and set to loop hundreds of times a day, victimising these salt-of-the-earth types who work at Tesco, B&Q or Kwik Fit, or are excited to extol the benefits of a new chocolate bar or paste for sensitive teeth. They are robotic representations of our retired traveling salesman, and, through the way they ruin and mock their own claims on authenticity and reality by parrot-patter repetition, they bear an eerie resemblance to those wannabe-authentic, ‘social commentary’ guitar bands foisted upon us by a hopelessly cumbersome and unresponsive major label machine.

It’s a machine that still believes the discovery of music is something that can be controlled or imposed upon a listener. Those days haven’t gone yet, but they are disappearing – there’s too much out there waiting to be found, but still, over the course of the decade, they paraded so many Views and Fratellis before us like snaggled-toothed, leather-clad saviours. As ‘social realism’ in music has itself ossified into a rhetorical template of spilt kebabs, the rhyming of the word ‘night’ with ‘fight’ and lascivious local lasses with conveniently alliterative or euphonious names (The Fratellis’ ‘Mistress Mabel’; The Kooks’ ‘Jackie Big Tits’; Kaiser Chiefs’ ‘Ruby Ruby Ruby Ruby’; The Wombats’ ‘Patricia The Stripper’) social commentary has become an advert for real life in itself – that the major labels, their bands and champions continue to market this parody as ‘authentic’ is a dual-crime of delusion and pretentiousness that jars with the escape so obviously offered by ‘glo-fi’’s immersive visual and sonic advertising.

Sat watching 24 hour news channels, the ‘real-life’ ads loop around again and again, endlessly, to the extent that you eventually move beyond irritation with their characters into feeling a kind of sympathy for them. You feel their pain as they reappear on screen only to relive the exact same moment over, as if they’re destined to live out their lives in Groundhog Day. There’s one particularly pathetic character in an advert for UK brokers Ocean Finance who seems to share not a single gene with the manically-animated, go-getting door-to-door salesman of my childhood. Every time I see him he’s out at the supermarket or the DIY warehouse worrying in monologues about his debts, only to be bump into and be patronised by smug friends already free of theirs, thanks, of course, to the good people at Ocean Finance. Reinvigorated and with a lightbulb symbolically aglow overhead, our would-be heroic, remasculated breadwinner returns home, only to find his overweight wife slumped on the couch, brew in hand, having festered there long enough to discover that Ocean Finance have their own TV channel. He needn’t have gone out at all.

Thunder stolen by this lazing hen, our man’s shoulders slump, his eyes roll despairingly and he retreats back into himself, a useless lump of meat and hide fated to repeat this heart-, ego- and libido-crushing scenario over, and over, and over, and over, and over, and over again, forever.

There is an incredible, inescapable sadness to advertising. It’s there in the way its characters are hopelessly trapped within its rigid narratives, and, with this spate of ‘reality’ adverts, denied even the luxury of ads of yore. Both being representations of fleeting, microcosmic worlds of their own, popular pop music – i.e. pop that makes money, and the charts – and advertising will go down together; as each repetition inevitably robs some iridescent lustre and novelty from the resonant image that makes you want to buy them (it can’t be coincidence that real, zeitgeist-snaring pop tunes are only able to exert their power for the length of time ads run on television before they’re pulled by execs).

Like advertising, pop music exists in a different dimension of time to the rest of us. It ages by the play or the view, rather than by the second in linear time. At the time of writing, Rihanna’s ‘Umbrella’ was approaching its 296th YouTube birthday (19,888,083 views), as ‘Feel It All Around’ crawled laxly towards its 1st (67,198 views). It’s miraculous that Rihanna’s song still vibrates with such a rare emotional energy. It’s that good.

TV ads will never enjoy complete obscurity – their commercial purpose precludes it; there is no desire to exist in an advertising underground. However, pop music made by lonely kids in their bedrooms thrives in obscurity. The heavily stylised, lost-FM veneer of ‘glo-fi’ and other post-generic pop music is ‘live fast, die young’ to advertising and mainstream pop’s ‘grow-up sensible’; as it manages to evade death by evading over-play. And, as advertising has claimed cold, hard reality as its stomping ground – and the music of wannabe-authentic, social commentary guitar groups increasingly rings false – the warm, soft music of Washed Out, Toro Y Moi, Memory Tapes, Future Trends and their ilk, travel-nostalgic adverts issued forth from a lonely provincial bedroom, could be seen as salvational escapism directed at these poor characters stuck in the unreal reality of their Ocean Finance ads. It has turned the tables on the advertisers, reversed the push and pull – the flair with which Ernest Greene has conjured the image of Washed Out at once empathises with, mocks and mourns the salesman who will travel no more, and the bands that, like minstrels turning up to find empty, rebelled courts, continue to pursue artistic careers in the same, lost fashion.

The man in the Ocean Finance advert stands for all the ‘things’ the internet has and will destroy – travel, milk floats, the suburban dandy, the high street, the salesman, the mud on your brogues, encyclopedias, the singles shelves at Wycombe Asda, the NME, MTV, pubescence, dark, rumbling underground bars, genre, flannel shirts, Dayve Hawk, swinging, blue ropes, Kwik Fit, toothpaste, ‘Jackie Big Tits’, Ocean Finance, libido.

Ernest Greene – standing for the photography and music of Washed Out – says to the man in the Ocean Finance advert:

“Look, I am lonely, I am advertising – like you, but better, warmer, more luxurious advertising; and people ‘get me’.

“Does it not sound like my music should be playing in the background of an advert for aftershave or perfume? Perhaps while a scantily clad man grapples with the silhouette of his water-dabbled beauty in sunset surf?

"They might be supping luxury drinks, or smoking fine cigarettes."

Ernest Greene offers Ocean Finance man a fine cigarette.

“Do I not sound like Miami Vice underwater, or an active youth recalled through a mind’s eye missing its contact lens?

“Surely that’s better than being trapped forever in a ceaselessly repeating limbo of debt?

“You are not real. You never will be again. Give up.

“I offer you an escape,” says Ernest Greene, like an ambassador from the internet’s dictatorial constellation, now, selling to the defeated salesman.

“We can honour the past – your past.

“But everyone has their own memories.

“Come and bathe in me, and ours.”

And with that Ocean Finance man wades out into clear as crystal, warm, blue Pacific waters and, sadness compounded, sadness relieved, winces as he stubs his big toe on the spine of a disintegrating travel brochure.