This article was originally published in 2017

“No-one really talks about them still, do they? Or writes about them?” It was about two years ago and I was in a bar in Berlin, talking to a German artist friend. Somehow the topic of conversation had steered round to the YBAs, those upstart conceptualists synonymous with the heady days of London’s 1990s art scene, and to Damien Hirst in particular.

“People in art magazines don’t really write about them, no,” I replied, “but newspapers do.”

At Frieze, London’s biggest art fair, last year, a whole new section of the fair was opened up in the main hall, specifically dedicated to ‘The Nineties’. But the likes of Hirst, Tracey Emin, and Sarah Lucas were conspicuous by their absence. Of the contributors to such once-seminal group shows as Freeze, Brilliant, Modern Medicine, and Sensation, only Richard Billingham, with his frank and sometimes lurid photographs of his own working class family, was here selected for inclusion. And despite their early championing of such artists, it is now some five years since work by the likes of Lucas, Emin, or Hirst has been reviewed in the magazine. A similar story is revealed by the archives of other well-known art magazines.

Between the covers of the national dailies, on the other hand, they are frequently to be found – and not always in the culture section. Hirst and Emin, in particular, have become characters as well-known for their personal lives and business dealings as for their work. For many observers they must seem like specimens of that peculiarly late twentieth/early twenty-first century phenomenon: famous for being famous.

Insofar as the whole meaning and mission, arguably, of the YBAs had always been to drag art out of the rarefied air of the trade papers and into the dailies, to launch one last assault on the already-crumbling border wall between art and life, they must be granted some degree of success, on these grounds if none else. The collective oeuvre of Hirst, Emin, Lucas – and of Gary Hume, Marc Quinn, Anya Gallaccio, Michael Landy, Gillian Wearing, Gavin Turk, Sam Taylor-Wood, Jake and Dinos Chapman, and so on – made clear distinctions between life and work, between what constituted proper materials and what just stuff, what made a site and what mere place, increasingly hazardous to determine. Everything that had been controversial about the art of the 60s and 70s, ideas once-scandalous drawn from pop, minimalism, arte povera, and conceptualism, they simply took for granted, applied as baseline assumptions, and weaponised gleefully, with a missionary zeal for self-promotion peculiar to a generation whose formative years were spent in 1980s London.

If finally, the YBAs added little that was genuinely new to the discourse around art, they nonetheless played the hand that they snaffled for themselves with enough chutzpah to ensure that they would at least be talked about – and be enjoyable to talk about. First feted by the popular press as thrusting Thatcherite entrepreneurs, then damned as abstruse out-of-touch elitists, it is worth remembering that Hirst was brought up in Leeds by a shorthand typist and a car mechanic, Lucas grew up in a council flat off the Holloway Road and left school at 16, Emin’s troubled childhood with single mum Pamela in a violent and abusive Margate is well known. How much of the mock outrage at their work and antics was little more than thinly-disguised horror at the sheer temerity of these upstarts who refused to know their place? A few decades earlier, art school graduates with their background might have been more likely to form bands. Instead, they made the business of being artists look and feel like being in a band. London, for better or worse (perhaps better and worse), would never be the same again.

It is twenty-five years since the announced arrival of the Young British Artists. And though at the time, the tag was more a matter-of-fact description than the marketing label we remember it as, it should surprise nobody that the name Charles Saatchi was close at hand. So closely associated with the group’s work has the former Conservative Party ad man been, buying early works by Hirst and Quinn, Emin, Turk, and others, that it has become almost impossible to speak of one without mention of the other, in spite of Hirst’s later claim that the pair were “never really drinking buddies.”

In March of 1992, the Saatchi Gallery, then still on the Boundary Road in St. John’s Wood, mounted the first in a succession of shows dedicated, as their collective title put it, to ‘Young British Artists’. The first in the series placed now-famous works by Damien Hirst and Rachel Whiteread alongside the slightly older Langlands & Bell and the less well-remembered John Greenwood and Alex Landrum.

What is perhaps most striking, looking back now, at the work exhibited there a quarter of a century ago, is how much of the aesthetic that would make stars of Hirst and Whiteread was already in place. Whiteread was already casting the emptinesses inside ordinary domestic environments. Her Ghost, moulded from the interior of an Archway Road flat that had been earmarked for demolition, was included in the show and plans for the similarly-realised House, which would win her the Turner Prize the following year, were already afoot.

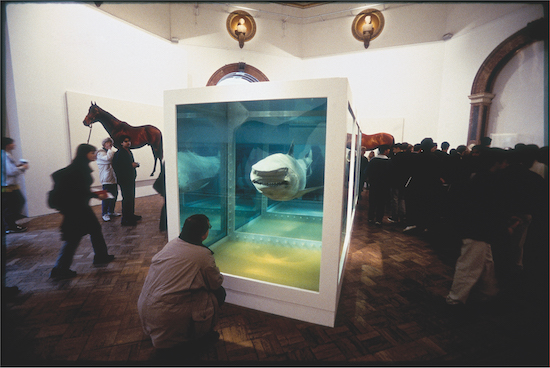

Hirst, on the other hand, though only 26 at the time, had already created so much of the work that he is now famous for that one is apt to ask what he’s been doing with himself since. The spot paintings, the medicine cabinets, were all even then underway and on display. His notorious eighteen-foot tiger shark, The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living bestrode the gallery like a colossus, in a vitrine built by the same company that made the aquaria for Brighton’s Sea Life Centre, prompting The Sun to mutter snarkily about “£50,000 for fish without chips”.

Two months later, the artist and critic Michael Corris, formerly associated with the Art&Language group, published a manifesto of sorts in ArtForum under the title “British? Young? Invisible? w/Attitude?” described, in a footnote, “the ‘new generation’ of ‘young British artists’” as a “cultural phenomenon formed out of specific needs expressed primarily in terms of a presumed national culture … brought to bear by historical responses to the collapse of British colonialism, its neocolonialist aftermath, and the prevailing consciousness of the subordination of early-20th-century English avant-garde in painting and sculpture to the Continental avant-gardes, and, domestically, to the practice of literature.” It ended, aping the manner of Vorticist magazines with a roll call to “Bless Critical Decor, bless Rachel Evans, bless Mariko Mori, bless Anya Gallaccio, and bless Hope.”

The specific abbreviation “YBA” would have to wait until 1996 to enter print, but according to Gregor Muir’s book Lucky Kunst it was already being employed as an “easy shorthand” in regular discussion, both within the group themselves and by their institutional backers, by the end of 1994. “During the mid-nineties,” Muir asserts, “young British art was packaged, branded, and shipped abroad.” Both the epithet and its snappier initialism played an essential role in this process of commodification.

Writing about Muir’s book in a column for The Independent at the time of its release in the beginning of 2009, Emin herself found herself, reading it, transported back “into an almost black and white art world of Britain, of fish and chip papers, roll-up cigarettes, carpeted galleries with hessian wallpaper and tiny little glasses of white, acidic wine; the art world, but not as we know it.” Muir describes arriving in a recession-burnt capital to discover a creative scene that was “fusty, parochial and dull” in which “snobbery was rife” and “experimentation occurring in corners of the art world that could no longer support it, and amateurish conservatism flourishing in parts that could.” The crash of 1990 would spell the end for one of London’s most innovative galleries, Nigel Greenwood, leaving few exhibition opportunities for the young graduates of Goldsmiths and elsewhere that were then just getting their act together. They responded with a series of more-or-less DIY efforts in East London warehouses and empty Soho shopfronts. London’s newfound prominence in the international art market owes at least something to their efforts.

Arguably, we might trace the origins – or at least the acceleration – of every violence committed by the contemporary cultural industries upon this city back to those early nineties years when Hirst and his colleagues were setting up Freeze, Building One, and The Shop: the gentrification of the East End, the growing inseparability of art and speculative finance, the commercial sponsorship of appropriation, and the many silences and exploitative practices stemming from and circulating around art as a business. When a group of artists has, by now, spent so long producing so little over any worth, it’s hard to feel sorry for their inevitable fall from grace, something that was already well underway long before the Momart warehouse fire in 2004 that destroyed significant works by Emin, Lucas, Hume, Turk, Whiteread, the Chapmans, and Hirst. By the winter of 2001, the Art Newspaper was already advising we “forget the Young British Artist phenomenon”. Meanwhile, the Telegraph was asking ‘Is the party over?’ quoting their former champion Matthew Collings, “The YBAs are not a triumph of art. Their popularity is misguided.”

So what more is there to rake over, a further fifteen years on? From this historical vantage point, the only people who look more ridiculous than the YBAs themselves are their critics. The spectacle of Norman Tebbit, the editors of the Daily Mail, and those idiots, the Stuckists, all jostling to stick the boot in, looks now rather like a parade of dull, grey men taking turns to cock their withered snooks at anything new and unfamiliar, crying “Con!”, “Barbarism!”, “This is not art!” like so many geriatric border guards over a frontier long since surpassed.

The other day I was in my local library and the old lady who served me, glancing at the copy of Muir’s Lucky Kunst that I was returning, said, “They are lucky though, aren’t they? I mean an unmade bed’s not art, is it? It’s just an unmade bed.” Leaving aside for a moment the possible layers of narrative embedded in the stains and detritus that spattered Emin’s cot, I’m tempted to suggest that any work that brings the whole question of what is and isn’t art into such public relief must be worth something. Like much of her work (and that of her contemporaries), there may be earlier, more original, more striking, more interesting, generally better works of conceptual art than Emin’s My Bed, but few of them have been so widely discussed, nor have they so widely disseminated amongst their spectators a sense of some entitlement to a part in that discussion.

If there is a lasting legacy to the group, it may lie in the possibility they revealed so brazenly a picture of a conceptual art that might just be good fun. They had, as Will Self noted not long ago, “the best parties”. And like Emma Goldman, I do not believe that a beautiful idea must demand the denial of life and joy.