"I don’t know how to write a big hit song", Andy Partridge sings on this album, and if there’s one way to sum up the frustration that XTC must have felt throughout their whole career, that’s got to be it. Frustration that neither their managers nor their producers seemed to understand what they were aiming for. Frustration that their record company went from being uninterested in them to really uninterested in them once Partridge’s stage fright got the best of him. Frustration as they watched other New Wavers such as Elvis Costello, Joe Jackson, The Jam, and U2 become household names while they languished in relative obscurity. The irony is that the song the line appears on, ‘Mayor Of Simpleton’, is about as pure a shot of Grade-A pop as you can find, a slam-dunk smash hit if there ever was one – it peaked at #46 in the UK.

Of course, they brought a lot of it on themselves. Obviously their refusal to tour was a big factor, as was their tendency to ignore any passing fads; while their first four records all fit in well with the post-punk movement, from English Settlement on they’ve felt like a band out of time. The band had previously been big on being able to reproduce their albums live, but now that they were no longer playing live, all sorts of crazy things were allowed to happen. In the years prior to Oranges & Lemons, the band found themselves trying hard to replicate the bands they grew up admiring – both under their assumed names as the Dukes of Stratosphear, and with the Todd Rundgren-produced Skylarking. All this ranks among the best work Moulding and Partridge ever did; maybe all they really needed was to be born 15 years earlier. It wound up breathing some life into the band financially, too – while Mummer and The Big Express tanked, Skylarking wound up being one of the most successful albums of the band’s career. Partially because it spawned their most well-known song (‘Dear God’, originally a B-side), and partially because it’s a really damn good album. But it was not really a great time for Partridge; he was going through turmoil both personally and professionally, as both his marriage and career seemed to be going down the tubes.

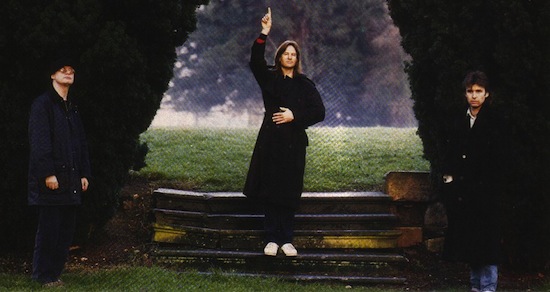

Oranges & Lemons is an attempt for the band to loosen themselves up; as the cover implies, they were going to be gaudish and colorful and nobody was going to stop them. After butting egos with the notoriously headstrong Todd Rundgren, the band hired Paul Fox to produce – a fan with no prior production experience. Where Skylarking was painstakingly edited and arranged, Oranges & Lemons lets everything hang out, and wound up as a double album that flies all over the map. The sort of outlandish tunes that previously wouldn’t have made it past the demo stage were showcased front and center here. Needless to say, many of the fans weren’t really into it; nowadays you generally hear it spoken of in terms of "Well, I like it, but…"

That’s a big "but". Indeed, Oranges & Lemons is the first XTC album that gives us a lot to complain about. If only it weren’t so long – sure, English Settlement is longer, but the songs there had a lot more substance. Here, they’re like candy bars; the first few are enjoyable, but fifteen in a row can make you sick to your stomach. If only the production was better – Paul Fox gives everything a shiny, in-your-face gloss that gives the album too much zip, the sort of thing Rundgren would’ve nipped out right away. Nearly every instrument is mixed to the forefront; it’s too well-arranged to be cacophonous, but there’s a degree of sensory overload, especially given the band’s newfound tendency to blast synthesizers in our faces. In only there weren’t so many instruments. And so on.

It didn’t have to be this way – there really is a great album buried somewhere in here, if you’re willing to find it. Hell, if you’re the kind of person who loves ‘Shake You Donkey Up’, this may be your favorite XTC album already. Partridge and Moulding come from a long history of overstepping their vocal boundaries, and writing lyrics to match ("I want to take you out and show you to the girls", Partridge sings on a song that is definitely about his penis) – and as ‘Wounded Horse’ on Wasp Star shows, they’d do this till the bitter end. But their songwriting instincts generally keep their heads above water. Indeed, the songs on Oranges & Lemons may press down hard on the irritating button, but there are good ideas lurking on most tracks. Some of this is hard to redeem – ‘Here Comes President Kill Again’ is a dull marching tune, Moulding sleepwalks through ‘Cynical Days’, and ‘Miniature Sun’ attempts to imitate jazz by overloading the listener with loud honking noises. But otherwise, ideas that should fail wind up working, through rich arrangements (‘Garden of Earthly Delights’) or undeniably hooky melodies (‘Poor Skeleton Steps Out’).

So ultimately whether or not this album holds up for you depends on how much you like the band’s boisterous side. While Partridge has matured a lot from the guy who barked all over ‘All Along the Watchtower’ on White Music, something seems to have brought those instincts back – perhaps having kids, which much of this album is a testament to lyrically. Only now he’s got a horn section to play with, and a producer who doesn’t seem able to tell him "no". But it’s not just Partridge – Moulding gets his goofball moment on the third song, with ‘King For A Day’, a chirpy single with more than a passing resemblance to ‘Everybody Wants To Rule the World’; exactly the sort of thing Rundgren might have a conniption about, but Fox lets it slide. As gimmicky as this album can be, there’s no denying that the fun factor is through the roof. Still, Oranges & Lemons is one of those albums that works better in pieces than as a whole. It does boast some of the band’s best songs; the aforementioned ‘Mayor Of Simpleton’ is about as good as pop music can get, and the closing ‘Chalkhills And Children’ realizes Partridge’s lifelong dream of writing a timeless ‘Good Vibrations’-type song of his own. Even if the rest of the album provokes an allergic reaction in you, it’s worth keeping for ‘Chalkhills’ alone. I’d also rank ‘One Of The Millions’ as one of Moulding’s best; it’s jangly, has great harmonies, and is instrumentally rich – basically everything he does well at once.

Alas, Oranges & Lemons signalled the beginning of the end for the band. Even though ‘Mayor Of Simpleton’ made a minor dent, the other two singles (‘King for a Day’ and ‘The Loving’) didn’t, and soon both Moulding and Dave Gregory found themselves working at a car rental spot to sustain themselves between royalty checks while recording their next album, 1992’s Nonsuch. Nonsuch was XTC in their full-blown adult phase; recorded with veteran producer Gus Dudgeon, it’s refreshingly more restrained than Oranges & Lemons was, and holds up a lot better today. Listening to it today, it feels like XTC realizing that it may be their last chance, and therefore putting everything they’ve got into making something timeless. But the result was business as usual for the band; heaps of critical acclaim, a few minor singles, and hardly a dent on the charts. From there they’d split with Virgin; we’d hear from them one last time with the double Apple Venus/Wasp Star which was released over a two year period, but as of now it seems doubtful that either member will want to get involved with writing new music again.

On one hand, this is a real shame; today, Apple Venus feels a hell of a lot more relevant and skillful than the sort of albums XTC’s contemporaries were making 20 years into their careers. On the other, their lack of success made it a lot easier for them to walk away once they ran out of ideas, and as it stands now, XTC’s discography is one towering, absolutely essential beast, from start to finish. For even when they massively stacked the deck against themselves on Oranges & Lemons, they still managed to create something that still endears in its own way 25 years later.