"What you need to understand", said Method Man, jabbing his finger towards me for emphasis, "is that the black man is GOD."

I glanced around. The dark interior of the Wu-Tang Clan tour bus, parked up next to the Kentish Town Forum, was illuminated only by a few flickering candles, and heavily scented with burning herbal matter. The faces of eight other Clan members, huddled in a tight circle around Meth at the table where I’d set up my dictaphone, solemnly nodded their assent.

At the gig I’d just seen, as a reviewer for Melody Maker, I’d been one of maybe twenty non-black faces in the whole building. The Wu-Tang Clan weren’t, yet, being touted to the white mainstream, and the band’s first UK show hadn’t been advertised in the Maker or the NME. It didn’t need to be. It sold out purely on the Wu’s existing rep among hardcore hip hop fans. Midway through, Method Man had taken the opportunity to preach some Five Per Cent Nation polemic. "Islam is the only true religion… this is the only true flag… the sun is man, the moon is woman, the star is the babies… we swam 9,000 miles to be free… you know what I’m sayin’?"

By the time my turn came, the Wu weren’t in the mood for meeting the press at all. Earlier in the day, Angus Batey of Hip Hop Connection magazine had witnessed tempestuous, door-slamming arguments caused because the band hadn’t been fed by the tour promoters, and believed they were owed payment from the record label for even giving interviews. And yet, here we were on the bus, nine pissed-off and peckish rappers and one outnumbered writer. In retrospect, I imagine they saw me as, in all kinds of respects, Part Of The Problem. Face like thunder, Method Man reiterated his statement. "THE BLACK MAN… IS GOD."

Swallowing something hard and jagged, I managed to squeak a conciliatory "OK…", and moved the conversation on. For me, it was one of the strangest and most uncomfortable moments of my journalistic career, one I’ll never forget. For the Wu-Tang, just another day. How did we all get here?

My journey to this fraught face-off in September 1994 involved more than just jumping on the 134 bus. At the time, I was deeply in the grip of a full-on hip hop phase. And when I say ‘phase’, don’t misunderstand me: I’d always loved hip hop (Public Enemy’s It Takes A Nation Of Millions To Hold Us Back was, and remains, my favourite album of all time), but for the previous seven years I’d been a massive goth, outwardly at least. Suddenly I’d decided to leave all that goth shit behind, cut off my hair and start wearing hip hop gear. (Not only the Grand Royal skatewear that any indie type could get away with, but imported Karl Kani stuff that you’d only recognise if you’d nerdishly studied Vibe or The Source.)

Understandably, many found this transformation hilarious. My nickname around the Melody Maker office became Price Cube. Pearl Lowe of Powder wrote to the letters page calling me "a K-Mart Beastie Boy". (I was mildly put out – those threads cost a bomb – but, as I’d been unkind about her in the previous issue, I was asking for it.) My friend and colleague Pete Paphides more diplomatically remarked "Wow, when you get into something… you really get into it, don’t you?"

He was right. I wanted my hit of hip hop to be unadulterated and unmoderated, not the pre-filtered version that usually made it through to white listeners. It wasn’t that the weekly music press, of which I was part, didn’t cover hip hop. But we always seemed to cover a particular type. Flicking through a pile of old papers from the era recently for the purposes of this piece, the names that jumped out were Gang Starr, Arrested Development, Disposable Heroes Of Hiphoprisy, New Kingdom, Ice-T/Body Count, The Goats, Credit To The Nation and Cypress Hill (who, a few weeks before the Wu-Tang gig, had headlined the Maker-sponsored Reading Festival). It usually tended towards the backpacker-friendly, characterised spiritually by post-Daisy Age liberalism and/or happy-go-lucky stoner vibes, and musically by tasteful jazz elements and/or familiar rock samples. Stuff that met you halfway. I didn’t want to be met halfway.

Not that my own listening habits were entirely hardcore, I admit. Thinking back to what I’d have been playing around that time, I was probably still hammering the shit out of It Takes A Nation Of Millions (and to a lesser extent Fear Of A Black Planet). I had Ice Cube’s Lethal Injection on heavy rotation. I was squeezing the last drops of joy from Cypress Hill’s Black Sunday. And I was deeply smitten with G-Funk, particularly that glorious trilogy of Doggystyle, Regulate and The Chronic.

Some time in early 1994 I was in Los Angeles, home of G-Funk, on an assignment to interview shoegaze survivors Ride. I have two abiding memories of the trip. The first is of an insane afternoon at the Beverly Hills mansion of Ride’s US promoter Ian Copeland (brother of Miles and Stewart), involving a pillow-sized bag of weed and a paintball battle in the undergrowth which Copeland, a Vietnam veteran, took with alarming seriousness, picking off his Limey foes with chilling brutality. (Those pellets can fucking HURT.) The second is of a moment late at night, kicking back in a room in the Mondrian Hotel that was bigger than anywhere I’d actually lived, flicking through the cable music channels for something that wasn’t the zillionth play of ‘Hip Hop Hooray’ by Naughty By Nature, ‘Nuttin’ But Love’ by Heavy D or ‘What’s My Name’ by Snoop. Suddenly, from nowhere, came something that blew my mind.

On a giant chess board, nine cowled, monastic, ninja-looking figures stood in position like human pawns, and took turns to step forward and state their case, intermittently brandishing martial arts weapons where other rappers might flash an Uzi. One of them claimed to hail from "the Shaolin slum", and contentious words like ‘nigga’ were obscured not with the bog-standard gunshot sound effect but the metallic schwing of a samurai sword. The track itself was like nothing I’d ever heard, a sparse arrangement consisting only of an uncompromisingly tough backbeat and a spindly, eerie, chromatic figure apparently played on the yangqin, a traditional Chinese hammered dulcimer. The act’s intriguing name was Wu-Tang Clan, and the single’s equally baffling title was ‘Da Mystery Of Chessboxin”. Here, at last, was something entirely new. And it had no intention of meeting anyone halfway.

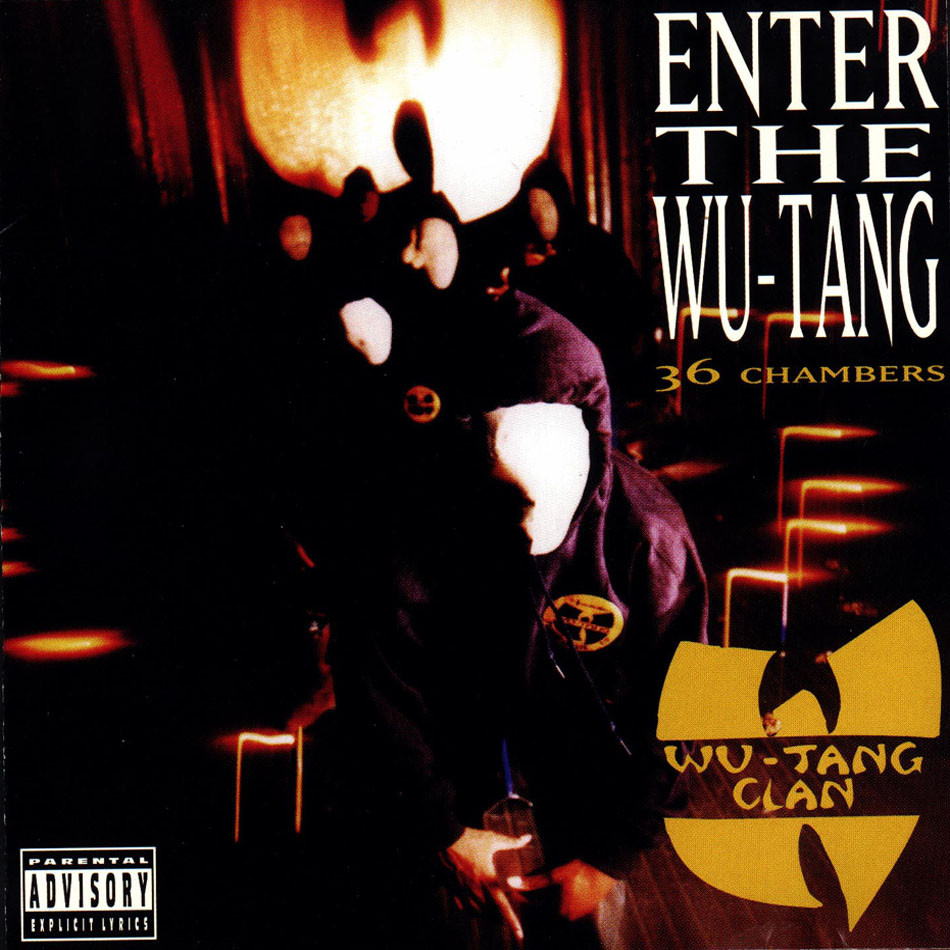

I found out everything I could about Wu-Tang Clan. ‘Shaolin’, it transpired, was a nickname for their home turf of Staten Island, the "forgotten borough" of NYC which housed the world’s largest landfill rubbish dump. They went by incredible handles like Ghostface Killah, Ol’ Dirty Bastard, Genius/GZA, Method Man, and Raekwon The Chef. The musical mastermind was Prince Rakeem aka The RZA, an early twentysomething who had, like most of the other members, been involved in petty crime, but turned his life around after being acquitted of attempted murder. ‘Chessboxin” was their third single, following the independently-released ‘Protect Ya Neck’ – on which The RZA had cannily charged each of the major players $100 for a solo spot – and ‘Method Man’. They’d been courted by legendary label Tommy Boy who, astonishingly in retrospect, opted to sign House Of Pain instead. Eventually they’d been picked up by Loud, and the band’s first album, Enter The Wu-Tang (36 Chambers), had come out in November ’93 but was yet to receive a proper UK release by RCA. It wasn’t on the schedule, wasn’t high-priority, and certainly wasn’t being serviced to the ‘white’ rock press. But it was way, way more exciting than anything that was.

Back in the UK, I banged on about Wu-Tang Clan to anyone who’d listen. Outside of the specialist hip hop press, I was the first British journalist to write about them. But I had allies: the Maker’s Neil Kulkarni, who knew hip hop better than anyone else at the paper, was another early adopter. When I declared 1994 to be the Greatest Year For Hip Hop – a claim which, with all respect to any other year you care to throw at me, may actually stand up – it was, to a considerable extent, due to the fact that The Wu were at large, and that album was on sale.

Enter The Wu-Tang (36 Chambers) remains one of the most astounding debuts from any artist in any genre. It’s an album which challenges you, from the very outset. Literally: the first voice you hear is a martial arts movie character saying things like "Do you think your Wu-Tang sword can defeat me?" and "En garde!" But aside from the belligerent insistence, backed up by kung-fu crunches and punches, that ‘Wu-Tang Clan Ain’t Nuthing Ta Fuck Wit’, it was an album which threw down a sonic gauntlet to the rest of hip hop. Just as Public Enemy had five years previously, the Wu-Tang Clan had made all other rap records sound instantly outdated. (Tellingly, when a 1986-vintage Beasties guitar chord is used to bleep out the F-word on ‘Protect Ya Neck’, it actually sounds older than any of the dusty snatches of Thelonious Monk on the album.)

As well as those brutal beats and Chinese dulcimers, The RZA made exquisite use of old jazz and soul samples (there can’t be many Wu-lovers who didn’t go out and track down, for example, Wendy Rene’s ‘After Laughter Comes Tears’). Admittedly, he was far from the first producer to do this. But whereas The Bomb Squad, on Public Enemy’s records, had crushed tiny fragments of songs into what amounted to musique concrete, The RZA allowed them to spiral outwards and unravel into skeletal shapes, more often than not involving a piano motif that was never intended to sound as chilling in its original context as it does on a Wu-Tang track. The effect was incredibly cinematic (a quality which would later find full expression in RZA’s work on soundtracks, most notably Ghost Dog and the two Kill Bill movies), and often unsettling, like icy fingers down the spine.

Even though the Wu’s obsession was with 1970s kung fu movies rather than horror or gangster flicks, the album’s sinister mood chimed with hip hop’s emerging Horrorcore genre: with the likes of Scarface, Bushwick Bill, (RZA’s own side-project) Gravediggaz and Snoop & Dre’s Murder Was The Case project, rap was taking a turn for the gothic with a lower-case ‘g’. (I actually played the Wu’s ‘7th Chamber’ in a DJ set at the Whitby Gothic Weekender, and perhaps predictably cleared the floor. The days when ‘Gravel Pit’ was packing the rock clubs all over Britain were still some years off.) But the patina of faux-Orientalism, which at first glance might have appeared a bolt-on gimmick, took the album beyond the noir and lent the Wu sound a precious otherness.

Against this backdrop, the personalities of the individual members jostled for prominence. Ghostface and Raekwon were the most technically gifted. Method Man oozed the charisma that would later land him the role of Cheese Wagstaff in The Wire. Ol’ Dirty Bastard, the roughneck loose cannon, was chaos incarnate, a clown in the Busta Rhymes/Flavor Flav mould.

Like Public Enemy before them, there was no attempt to disguise the Clan’s affiliation to Nation Of Islam politics: "I’m making devils cower to the Caucus Mountains", boasted U-God on ‘Da Mystery Of Chessboxin”. (To this day, bow-tied NOI emissaries continue to hawk The Final Call outside Wu-Tang concerts even though, in the two decades since that night in Kentish Town, the racial mix of the audience has pretty much inverted itself.)

But, as well as being confrontational and compromise-free, it was also funny as fuck, the perfect balance of the puerile and the profound. Take, for example, the bit where GZA, after some epic fronting, taunts an imaginary rival with "You become so pat as my style increases/What’s that in your pants? Aah, human faeces!/Throw your shitty drawers in the hamper/Next time come strapped with a fucking Pamper…" Or ODB’s gross-out couplet "I get into shit, I let it out like diarrhoea/Got burnt once, but that was only gonorrhea…" Or Ghostface bragging "I blow spots like Waco, Texas". Or RZA’s laugh-out-loud "Holding meth got me open like fallopian tubes".

Some laughs caused by the Wu weren’t even intentional: for years, I thought Ghostface was claiming to be "tough like an elephant’s arse" (it is, somewhat more logically, "elephant’s tusk"). Other times they were opportunistic responses to circumstance, like the genius radio edit of the storming, Stax-y ‘Shame On A Nigga’, renamed ‘Shame On The Nuh’, wherein the offending word was highlighted with an exaggerated grunt of "NUH!" to render the censorship both more obvious and more absurd.

And everyone knows the "torture, motherfucker" skit, as frequently-quoted by hip hop fans as is the bloody Parrot Sketch by Pythonists. Method Man and Raekwon take it in turns to devise ever more outlandish ways to bring the pain, from anal branding with a coathanger to testicular pummelling with a spiked bat to tongue-piercing with a rusty screwdriver to defenestration by the penis. Eventually, Meth trumps them all with a threat that "I’ll fuckin’… I’ll fuckin’… sew your asshole closed, and keep feedin’ you, and feedin’ you, and feedin’ you, and feedin’ you!"

For all the dicking about, much of it is unapologetically grim. The Gladys Knight-based ‘Can It Be All So Simple’ was a counterpoint to the prematurely rose-tinted nostalgia which, with tunes like ‘Back In The Day’ by Ahmad, was creeping into hip hop. Raekwon’s version of nostalgia, recounting his origin story, involves catching a bullet and a drug-addicted father, then Ghostface brings us screeching into the equally bleak present tense: "Brothers passing away, I gotta make wakes…"

There’s plenty of violence and a fair quantity of drugs to justify that Parental Advisory – Explicit Lyrics sticker, but Enter The Wu-Tang is, for a rap album of its era, peculiarly sexless. Sure, you’ve got Method Man talking of "making bitches squirm" and being a "P-A-N-T-Y-R-A-I-D-E-R", you’ve got Ghostface claiming to be "getting my dick rode all night" and you’ve got GZA suggesting we "bring out the girls and let’s have a mud fight". But there’s none of casual glee of Snoop’s "bitches in the living room gettin’ it on and they ain’t leavin’ till six in the morning" here. The most elongated reference to sex occurs on ‘Tearz’, but it involves someone having unprotected intercourse and contracting HIV. Like I said, grim.

Occasionally it manages, a la Tarantino, to be both fucked-up and funny at the same time. "Is he fucking dead?" repeats one member to another with disbelief. "What the fuck do you MEAN ‘Is he fucking dead’, guy? The n*gga layin’ there with his fuckin’… all types of fuckin’ blood comin’ out of him."

It’s endlessly quotable, and packed with hooks. Not in the traditional sense, but barbed micro-moments which snag your brain. Bits you look forward to every time, and that send physical shivers when they happen. Like the first proper line of ‘Bring Da Ruckus’, the opening track: "Ghostface, catch the blast of a hype verse!" Or that delicious moment on "C.R.E.A.M." when the Charmels sample kicks in.

When I think of 1994, as much as I think of The Holy Bible, The Downward Spiral and Dog Man Star, I think of Enter The Wu-Tang. No late night session with friends was complete without it, and it travelled with me so frequently that my copy is scuffed to fuck. Like all the great groups, the Wu-Tang Clan had created their own universe around them. They had an aura, a self-created mystique, a distinct aesthetic (laid out in the Wu-Tang Nation documentary, which incorporates lengthy clips from martial arts exploitation movies), a philosophy (albeit one largely borrowed from the aforementioned movies), their own slang vocabulary that made you feel like an insider once you’d cracked it, and that ineffable quality of FUCKINGHELLNESS where simply knowing that a certain group exists in the world can alter the way you see, think, talk, walk.

Their impact was significant in ways which went beyond the way they sounded (although second-rate Wu soundalikes did proliferate for a while). In hip hop terms, this was very much The East Coast Strikes Back. The Los Angeles had dictated the agenda for years, but the Wu – along with Mobb Deep and, slightly later, Nas – were at the forefront of a New York revival. And precisely because they rolled so ridiculously deep, they were able to establish a new kind of industry model. RZA licensed individual members out to sign solo deals, allowing him, with the managerial muscle of Oli ‘Power’ Grant (the Wu’s equivalent of Death Row’s Suge Knight) and Mitchell ‘Divine’ Diggs (RZA’s brother), to create a whole empire extending from music to clothing. (Yes, I did own a pair of those giant Wu Wear jeans. I know. I know.) You can’t tell me that Jay-Z and Sean Combs weren’t watching, and learning. And the whole Odd Future/OFWGKTA set-up is essentialy Wu-Tang redux.

This approach also fostered career longevity of a kind which rap acts still weren’t expected to possess, but which the Clan craved. As Method explains to an interviewer in a mid-album intermission, "We ain’t tryin’ to hop in and hop out…" And it was a thrill, with Enter The Wu-Tang still ringing out, to realise that there was more to come from the Killa Beez. In quick succession, all produced or part-produced by The RZA, a run of phenomenal spin-off albums started to drop. In rapid succession came Niggamortis by the aforementioned Gravediggaz, Method Man’s Tical, ODB’s Return To The 36 Chambers, Raekwon’s Only Built For Cuban Linx, GZA’s Liquid Swords and Ghostface Killah’s Ironman. The momentum couldn’t last, and the Wu’s own follow-up, 1997’s Wu Forever, was overdue, over-long and overcooked. But the good shit still kept coming in faltering fits and starts, with RZA’s alter-ego vehicle Bobby Digital In Stereo, Wu-Tang affiliate Killah Priest’s Heavy Mental, and the Wu’s own excellent 8 Diagrams being just three post-golden age highlights.

As a collective, the Wu never matched their debut. Listening to it now – getting a fix of what Raekwon, on ‘Can It Be All So Simple’, called "1993 exoticness" – it still sounds unfathomably tough, irreducible, unbreakable. It isn’t just that it hasn’t dated. It created its own fucking calendar, one that the rest of the world struggled even to decipher.

What you need to understand is that these black men were GODS