For the many who buy into the narrow (and sadly pervasive) Britpop-centric account of recent music history, the Verve story begins in 1994 and their patronage by the Gallagher brothers, with Noel writing ‘Cast No Shadow’ about Ashcroft, and Ashcroft apparently returning the favour by naming The Verve’s second album, 1995’s A Northern Soul, in honour of the Oasis leader. But this version of events completely disregards their one true masterpiece – debut album A Storm In Heaven, released by Virgin subsidiary Hut Records in June 1993.

A sign of its lowly standing is that it just scraped the NME’s list of the 500 greatest albums of all time, in with a whimper at No 473, beaten by the good, yet inferior, A Northern Soul (390) and the bombastically formulaic Urban Hymns (128). Not that one should get too hung up about subjective lists on websites, but it is representative of how the album is seen in critical circles – it is barely mentioned in any of the dispatches referencing the period. There’s a great story on the YouTube link for the full album stream of A Storm in Heaven that sums up the prevailing attitude, as one poster recalls going to a Verve gig around this time and calling out for ‘Slide Away’ (the first American single release from A Storm In Heaven) and being told, “That’s an Oasis song, mate”, by the bloke standing next to him.

When they first emerged, Verve (before they were forced to add a “The” by the American jazz label of the same name), like many bands of the time, were lumped into the shoegaze scene pretty much by dint of the fact that their moniker was singular as per the vogue (Ride, Lush, Moose etc), and lead guitarist Nick McCabe’s desire to make his guitar sound like anything but what it was via a vast array of delay and effects pedals à la Kevin Shields. But Verve were from Wigan, not the Thames Valley, and at the outset Ashcroft didn’t even wear shoes – not since Zola Budd has one human being’s eschewing of footwear caused such consternation in the media – and “Mad Richard” (as Melody Maker unforgettably pegged the shoeless freak) was very much gazing at the stars.

In fact, on A Storm In Heaven’s opening track ‘Star Sail’, Ashcroft is ensconced in Heaven in an otherworldly rapture, peering through the clouds to the world below, enveloped in McCabe’s magisterial, reverb-soaked guitars. “Hello, it’s me, it’s me,” he beseeches. “It’s me throwing stones from the stars on your mixed up world.” Reined in from the epic Doors-meets-Can space-rock indulgences of their previous singles, ‘She’s A Superstar’ and ‘Gravity Grave’, ‘Star Sail’ clocked in one second shy of four minutes. Part of the reason for this sudden and much-needed focus was the presence of the producer John Leckie, as Nick Southall revealed on his excellent piece on the album for Stylus in 2003: “Verve went into the studio with half a dozen riffs, half a dozen half-baked lyrics and a thousand ideas of ways to reach the sky. Leckie managed to seize the controls and apply the necessary degree of restraint and maturity, guiding the band back down to earth when they threatened to fly too close to the sun.”

Ashcroft’s spaced-out hippy schtick was very much part of the debate at the time, with writers trying to ascertain whether he was genuinely “on one”, the elastic-limbed Jagger doing Yoga on shrooms of the 1992 Camden Town Hall performance, or just playing the role of tripped-out, mystical shaman. Prior to the band he was studying philosophy, religion and theatre studies, all areas covered by his “Mad Richard” persona. Like Brett Anderson of Suede, Ashcroft was adamant about the need to resurrect the notion of stardom during a period where these sort of aspirations were frowned upon. Given how quickly he reverted to conventional rock star tropes after being abducted by the Gallaghers, it’s no wonder his authenticity was called into question, but this doesn’t make A Storm In Heaven any less dazzling.

Not that all the music press were in agreement – Vox magazine gave it an underwhelming 6 out of 10, concluding that it was an album where “song structure and silly things like choruses are subservient to atmosphere and vibes”. This was partly true, but ignored the euphoric ‘Slide Away’, very much a “proper” song (it scraped into the Top 100 of the UK Singles Chart) with a verse and a chorus where Ashcroft sings, “I was thinking maybe we could go outside/ Let the night sky cool your foolish pride/ Don’t you feel alive?/ These are your times and our highs”, while McCabe lets loose hurricane-force flurries of distorted riffs.

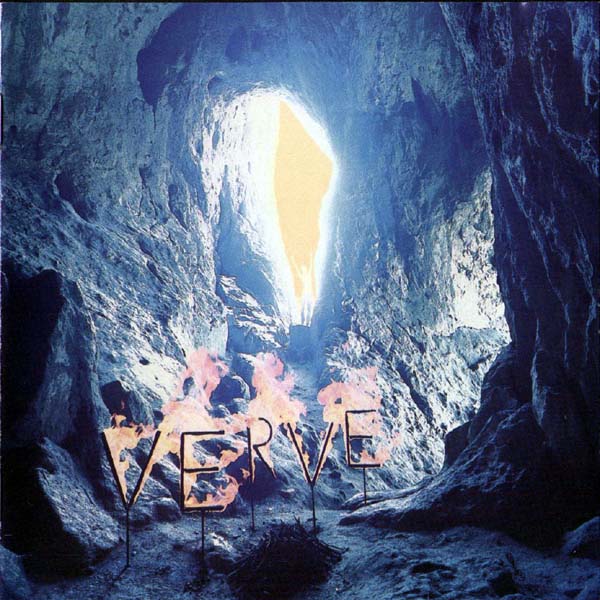

Vivid lead single ‘Blue’, the missing link between Murmur-era R.E.M. and Loop and driven by drummer Pete Salisbury’s relentless beat, was also a linear construct. In the video Ashcroft, with his sunken junkie cheekbones dug out of his face with a spoon, shakes maracas like a demented marionette and elbows his way through a crowd of moshers and female face-lickers in a subterranean club scene. The clip pre-dates the aggro Ashcroft barging his way down Hoxton Street in ‘Bittersweet Symphony’. At the end the band all emerge, wide-eyed, from Thor’s Cave in Staffordshire, the one from the album’s cover (designed by Brain Cannon, who would go on to do all the artwork for the first glut of Oasis releases), blinking into the light like astronauts returned from the (dark side of the) moon.

However, tracks such as ‘Already There’ really show this era Verve in all their glory, bringing Pink Floyd atmospherics into play (producer Leckie was the engineer on Dark Side Of The Moon) and McCabe revealed his versatility, starting by dripping delicate, trippy guitar fills over Salisbury’s subtle drums. “Seen it all, I’m already there,” sings a disembodied Ashcroft, having ingested enough psychedelics to make it to the other side without carking it. The song shifts effortlessly through the gears until Ashcroft is chuntering away in a messianic trance with McCabe’s glowing, incendiary riffs and the groove of Salisbury and bass player Si Jones who, like Mani, could inject a dose of lithe funk into even the whitest of male rock histrionics.

It wasn’t just the textured, ambient music that was the antithesis of what Britpop would come to stand for. Ashcroft, when he wasn’t howling into the void, could also write lyrics that reflected a gentle, thoughtful soul. On the soothing ‘Beautiful Mind’ he ponders, “A beautiful mind or a beautiful body”, before swiftly deciding, “I know which one I’m gonna end upon” – a million miles away from “She’s got one in the oven/ But it’s nothing to do with me” and all the horrible unreconstructed new-Laddism beloved of the Britpop massive. On the raging ‘The Sun, The Sea’ Ashcroft details an intense, head-fuck relationship between two people off their noggins on strong pharmaceuticals. “She calls me the sun, the sea”, he sings, which is a lot better than being scolded for forgetting to put the bins out. “Can I guide you?” he requests, before losing his shit to McCabe’s tidal waves of feedback and skronking free-jazz saxophones from the in-demand Kick Horns. Soon, parping brass would be a pre-requisite for all indie guitar bands, but here was a way of harnessing the sound without one iota of misty-eyed colliery band nostalgia.

More wild brass adorned the conclusion of the crazed and elemental ‘Butterfly’, memorably described in meteorological terms by the Graveyard Poet on Julian Cope’s Head Heritage site: “Gusts of wind and rain, flashes of thunder and lightning, rolling vapours. Guitars layered atop one another build and build until the clouds burst. The wanderer (and the listener) is caught out in the weather as maddening saxophones and trumpets freeze the downpour into hail, ice, and snow which plummet in a blizzard upon the lost soul as he struggles to find his way back home.” There are even flutes on the rambling ‘Virtual World’; the meandering, fluttering flutes beloved of prog rocks bands like Jethro Tull, but rather than this being unwelcome, it is another sign of the musicality of the record. It was practically unheard of for bands of this period to embrace sensitive woodwind instruments. Salisbury utilises soft hands on the percussion, while Ashcroft sings with an eerie falsetto over McCabe’s evocative acoustic strumming.

Ashcroft, the man who stated he was “Born to fly” on debut single ‘All In The Mind’ was brought crashing down to Earth by his association with the Gallaghers; the saucer-eyed loon of the band’s early days ironed flat by Liam and Noel’s boorish baloney, moving into egotistical rock star and dreary singer-songwriter territory with frightening ease. The band, with a crushing inevitability, fell with him. “It’s interesting to note that some of the bands brought to mind by Storm… have gone on to become flabby, globe-straddling dinosaurs. Verve have this in them,” noted Andrew Smith, presciently, in Melody Maker in May 1993.

“Maybe with the new LP, A Storm In Heaven, the doors are finally being broken down as far as expression on record, and expression as far as the band are concerned,” Ashcroft told Lime Lizard in an interview published around the album’s release. “The way I look at it is that it’s time for people who want to create to create, and people who want to be out there in mediocrity to sink.” Unfortunately, Britpop valued mediocrity over creativity, and the band’s inspiration diminished as a result. The Verve aren’t the only band in danger of being remembered for their worst songs, but there’s still time to set the record straight.