“Modernity is the transient, the fleeting, the contingent” the poet Charles Baudelaire wrote in The Painter Of Modern Life, at once captivated and repulsed by the metamorphosis of Paris around him. Many artists since have tried to convey the spirit or pathology of modernity in specifically modern terms, attempting to capture its sense of motion, simultaneity, alienation, fragmentation and multiplicity through various creative tricks – the cut-up, the montage, the dérive, the found text, stream of consciousness, perspective shifts, poems serenading pylons, Orpheus wandering the tunnels of the tube, and so on. While it’s arguable that the simple miraculous technology of the mirror remains undefeated in terms of reflecting life, modernist innovation did lead to many great works and all manner of pompous if still interesting dreck, as well as a century of spirited attacks from reactionaries and revolutionaries alike – the Bolshevik Karl Radek’s view of James Joyce’s work as “A heap of dung, crawling with worms, photographed by a cinema apparatus through a microscope” for instance.

In musical terms, modernism had an eventful adolescence – Futurists incorporating aeroplane propellers into orchestral arrangements, experimental symphonies provoking ‘riots’ etc. – before, it seemed, settling into supercilious middle-age in the academy, early retirement, and untimely ignominious death. Except, of course, the spirit (and pathology) of modernity never really died, not in music at least, partly because its central questions – What is it like and what does it mean to exist in the modern metropolis? And what does it do to us? – are still unanswered and fertile. Pick any movement in left of centre music in the past hundred years and you will find artists, to varying degrees and in varying forms of course, engaging with these questions, either through direct confrontation (whether it’s, say, The Fall or Wu-Tang Clan) or by fleeing from them into the countryside. Some artists, like Loscil for example, have managed both. Just as music soundtracks our experience of cities, so too cities shape their own soundtracks. And if it appeared that modernism was fading, at least from its epicentre of Paris, it was only because high-brow critics had failed to keep up with it, neglecting to notice other cities where it was continually being reborn – Chicago, Detroit, Düsseldorf, Manchester.

Given how fleeting and transient modern life can be, it’s easy to overlook the third and most important part of Baudelaire’s observation – contingency. By the late eighties, the various forerunners and Depeche Mode-esque incarnations of Underworld had run aground. The cult of youth promoted by the incubi music industry would allow them little room for a second or third chance. Karl Hyde and Rick Smith were now, and you’ll have to forgive my language, in their thirties. Their moment had seemingly passed, and obscurity awaited. The past, however, is not the present or the future, no matter what it contains. There are always other possibilities. As Baudelaire implied, one of the curses of modernity is that things will not remain the same. It can also be its redemption. Already orbiting, given their synth-pop beginnings, Hyde and Smith were soon absorbed in the emerging rave scene, though it took the fortuitous appearance of The Stone Roses’ ‘Fool’s Gold’ on MTV to persuade Karl Hyde to leave his role as a guitarist in Debbie Harry’s band in the US and return to the UK. The addition of DJ Darren Emerson added ideas and energy, while the model for their approach came not just from the minimalism of techno but also a beloved album of their youth – Bowie’s Low, particularly stripping back everything to its basic elements and reconfiguring from there, having the confidence to be minimalist and playful, letting the music breathe and move without restraint or meddling, and the courage to not know where it was all going but go there anyway.

This is immediately evident from the beginning of their rebirth. Initially, Dubnobasswithmyheadman does not feel like an urban album at all. ‘Dark And Long’ is brilliant and seductive but it is expansive, nocturnal, airy. It sounds like outland music. Its rhythm is that of the repeating white lines of a highway. Its space is that of the vast reaches between cities and seaboards. As new or rather renewed as it sounds, it is also subtly reminiscent of earlier music, yet only in the sense of using the same palette. Kraftwerk’s autobahn. Lanois and Cooder’s ambient-country landscapes. It is, as the band have underlined, as much the trance of Steve Reich as that of rave tapes. A drone floats above the pulse of the road like a Morricone harmonica, like hovering lakes of cloud in the colossal night skies of the American Mid-West. Which is where it originated, alongside the inspiration of reading Sam Shepard’s Motel Chronicles (“That night we crossed the Badlands. I rode in the shelf behind the back seat of the Plymouth and stared out at the stars. The glass of the window was freezing cold if you touched it”). Hyde’s time as a session musician was not wasted. His experiences of crossing the States to play in Prince’s Paisley Park studios in Minnesota inhabit the song. Inhabit being the operative word for Underworld. It is music that you are drawn inside of. This is what the best electronic dance music does. You lose track of your surroundings and maybe even yourself. This is an effect that is as simultaneously thrilling as it is soporific (in the best possible sense); one thousand listens and it remains as if the first time.

The album is headed for the city, and we arrive with the second track. ‘Mmm… Skyscraper I Love You’ begins atmospherically with the kind of shimmering surveying a new world ambient washes of synths familiar to Future Sound of London or The Orb around that time (there’s even a hint of Pink Floyd in the distorted bird calls and scene-setting). The layering tribal rhythm is enlivened, periodically, with a descending drum fill. When the vocals comes in, its character changes again. It’s more knowing, more mischievously kitsch (“And I see Elvis!”) than the opener. Where once their electronic forefather Gary Numan had painted a nightmarishly ambivalent dystopian urban scene, in ‘Down In The Park’, here there is a postmodern shrug towards “Porn dogs sniffing the wind for something violent they can do”. Hyde wrote the lyrics first flying high over New York and then walking its streets, jotting down scraps of sights and sounds on streets corners, fishing in those the fleeting transient rivers of which Baudelaire spoke. It consisted of “stuff which I’d collected wandering round the New York streets over the course of a week", as he told Melody Maker. “I got some of it out of The Village Voice and Screw magazine, other parts I wrote in an alleyway in Greenwich Village at four in the morning. When I got back, I cut the various lines up and then made a montage. It’s kind of a Cubist way of writing. What I’m trying to do is paint around subjects instead of focusing straight in on them.” So, we find waitresses, no smoking zones, crack heads, a beggar’s dog, midnight trains, phone sex, Christ on crutches…

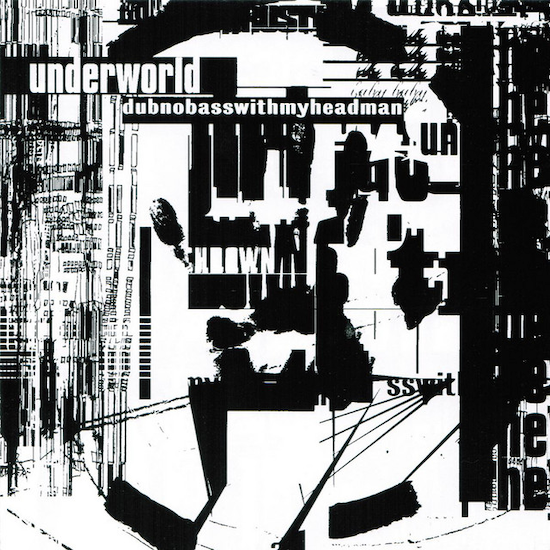

This modernist technique would serve Underworld well. It proved, if proof were necessary, that dance music could have its poets. And there is a book of the same name as the song which Karl Hyde brought out with John Warwicker, as part of their Tomato collective. Effectively a visual art/concrete poetry/explosion of typography and architecture project, its self-description encapsulates not just the essence of its song but something of Underworld themselves, being a “map of a journey through the streets of New York. Crosstalk & chaos: overheard, followed & abandoned, words/fragments from concrete. It is not only a reality but a memory of experience. Everything is in the present moment. It forms a cyclic series of impressions & expressions which occurred over the course of several months but which could just as easily occurred within a few seconds. ‘Read’ it as you would ‘read’ a film. Does a thing exist if the individual does not experience it directly? The city is always there, pulsing, alive, growing: rejoin the flow. Listen to your thoughts. Listen to your thoughts. Do you know what you want? How far do you want to go? No words necessary.”

The rest of the album plays with all the dynamism, pacing and unity of a live set. This is obviously a result of the immersive quality of the dance scene but it also calls to mind the instruction by Lou Reed on the sleeve notes of New York, a crucial influence according to Hyde, to treat the album “as though it were a book or a movie.” Whereas life in Reed’s city still moved slowly enough to be able to discern characters and narratives, for Underworld the experience is shattered and propulsive. It is a city of stolen glimpses, where even the dignity of a squalid denouement is denied to its citizens. They share with Reed, however, the benefits of being urban explorers who are from peripheral places (the places where rave really took off incidentally) and therefore can see even the jaded siren qualities of the metropolis, and the self-destruction therein, with keen voyeuristic eyes.

Musically, the album’s inventiveness is threaded through what feels like seamless material. All of them build, many of them are basically bangers, and there’s an ambient house quality throughout, as well as trust in the listener, that carries us along. ‘Surfboy’ is effervescent clattering space-age dance, with dub-inflected echoes of Adrian Sherwood and Zulu Nation electro, while ‘Spoonman’ is full-on head-fuck techno. ‘Tongue’, by contrast, is a languid island of peace amidst the rush, an ambient-shoegaze track that sounds like but predates the equally blissful ‘Rutti’ by Slowdive. ‘Dirty Epic’ continues the serenity, albeit with lyrics, sang with hints of New Order, fixated on the fallen glamour of a city on the plains. The album reaches a crescendo with ‘Cowgirl’ and its ambiguous robotic "an eraser of love" / "I’m a razor of love" refrain. It is not just a peak of Dubnobasswithmyheadman but, like non-album tracks ‘Rez’, ‘Dirty’, ‘Spikee’ and ‘Dark & Long – Dark Train’ (all collected in the deluxe edition reissue), one of the great peaks of dance music. The chillout tracks that follow, ‘River of Bass’ and ‘M.E.’, owe the most to the group’s past lives and, though not entirely successful diversions, demonstrate their dexterity. To all intents and purposes though, we took off into orbit with ‘Cowgirl’ and anything afterwards is being sent through a distant transmitter.

Modernity is transient and fleeting. Thirty years later, cities are not the same places, neither are albums, and neither are we. There are so many themes of change and repetition in Underworld’s lyrics and music, and you would expect a tinge of melancholy at this distance, yet joyously, there is little regret to be found, however grimy it gets. This is music that elevates being in the moment. What Underworld have achieved as a group is remarkable, not just with a tune as ubiquitous as ‘Born Slippy’ (an anthemic cry for help) or a spectacle as stunning as The Tempest-themed Olympics ceremony. Underworld remind us that moments and places that are disposable or debauched or transitory can be worthy of attention, or even be considered art, that these too are life, and in noticing them, you are honouring something deeper. This may sound worthy but the incidences themselves are not – the frantic dash for the last train, the drunken confessional moment staring at graffiti above a urinal, the glimpse of an illuminated room from a passing taxi, a shredded barely-legible poster or a neon sign above a backstreet door, a lucid moment in a ket-bumping pisshead’s lost night, a chant in a Romford street or a Manhattan canyon, a billboard on the A13 or Times Square, a whispered sentence from someone you will never see again.

Underworld have never forgotten the third part of Baudelaire’s quote. They have adapted to contingency, changing completely when they’d been written off, then aiming to renew themselves with each release. Sometimes it has worked. Their excellent psychogeographic Drift series was a continual touchstone for me during lockdown and its aftermath, crisscrossing London on the tube, when trains were still largely empty. It fitted, mainly because Underworld are a group of motion even at times of stasis, a group who find meaning in the recording of apparently meaningless things, a group who recognise that truth might be found more in fragments than in narrative, and such times abound. They are the music on headphones and the music of the streets beyond and the alchemy when the two seem to merge. Karl Hyde has referred to his songs as journeys and maps and – while they serve exceptionally well as soundtracks to any trek across any city, by any means and in any state of mind – where they come truly into their own is in showing us that no two journeys are ever the same. Everything can change depending on what we pay attention to. It’s not simply that the city can be different. The wonder, exemplified by Underworld, lies in noticing that it already is.