Robyn Hitchcock’s career, for want of a better term, shows a man as squarely out of time as it’s possible to be this side of a Bill & Ted movie. Had he arrived after the mid-Nineties, when pop music’s past began to telescope, everything went up for grabs, and the only truly unfashionable music was that of the immediate past, he might have done rather better for himself. But his band, The Soft Boys, made their first recordings in 1976. Setting out your stall as a psychedelic visionary at the exact onset of punk could be seen as an act of almost suicidal synchronicity. Never let it be said of Hitchcock that he blew with the breeze.

“We were all a bunch of very non-confrontational, uptight, middle-class kids,” Hitchcock would later say of The Soft Boys. “When everyone else was throwing beer glasses at the stage and putting safety pins through their noses, all we wanted to do was eat cucumber sandwiches.”

Not that Hitchcock’s music bore any but the most superficial of resemblances to the overstretched dawdles of the worst late-60s / early 70s drugs bores whose legacy punk supposedly aimed to overthrow. (This is an oversimplified hindsight narrative if ever there was one, but that’s another story.) John Lydon may have felt obliged to hate Pink Floyd (which he didn’t, despite what it said on his shirt). But Hitchcock, perhaps the only notable figure in pop to move from London to Cambdridge in pursuit of that vocation, rather than vice-versa, was always more Syd Barrett than 70s Floyd – indeed, more Syd Barrett than anything, albeit possessed of a lucidity that sadly escaped Barrett some time around 1968. His songs veered towards the taut, tart and tuneful, and rarely had the time to spin around and blink, let alone meander.

The Soft Boys weren’t that far adrift from the punks. They grew (as did many punk outfits) out of a pub-rocking covers band with the raw garage feel that usually had little to do with such hip forebears as The Stooges and The New York Dolls, and a lot to do with less-than-total instrumental proficiency – albeit The Soft Boys actually wanted to be proficient. Without Hitchcock, that’s probably all they ever would have been: another Cambridge pub band, too stuffy and fussed about musicianship to be punks, too uninspired to be anything else.

But Hitchcock was a highly gifted songwriter, whose songs prefigured and influenced the 60s-tinged revivals in both Britain and the US during the 80s – and surpassed much of them, at that. Peter Buck has gone on record as saying that R.E.M. were more influenced by The Soft Boys than by The Byrds. By the time R.E.M. released Radio Free Europe in 1981, The Soft Boys were defunct.

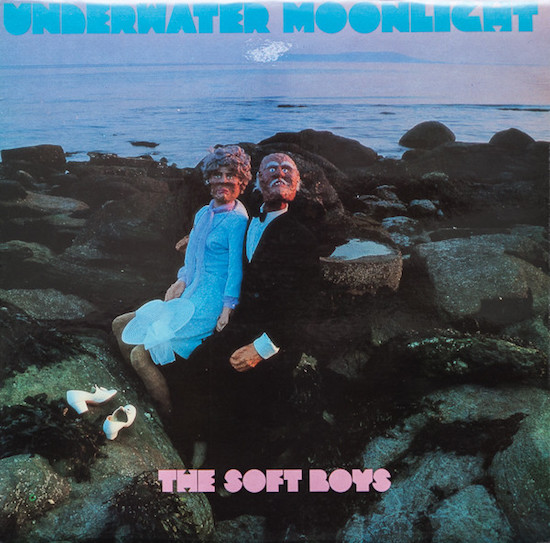

It’s one thing to be influential, another to stand the test of time. Often, “influential” is a word applied to bands too affectionately remembered to be described as, “Dated, and quickly superseded by those who improved upon their ideas.” Fortunately for The Soft Boys, they made Underwater Moonlight, an album which could hardly date as it wasn’t in the least bit of its time, or any other, and which is nigh-on un-improvable. The familiar assertion that a record, “Could have been made any time in the last [x] years” simply doesn’t apply. It’s not fey enough to have come from 1966’s school of tea-and-crumpets pysch. It’s too knowing to have originated in 1968, too concise to have trundled out of 1973. It sounds too little like a brain haemorrhage recorded on a dictaphone for 1977; it is nowhere near angsty, arty or overcoated enough for 1980 (when it was made); nor is it sufficiently winsome for the 1989-91 jangle epidemic. It’s very, very odd.

Of course, Hitchcock was fairly odd himself, in that reassuring, English, non-sequiturial way frequently and inaccurately labelled “surreal”. It was a family trait, it seems. Hitchcock recalled of his father, “He once wrote a book in which Stonehenge was stolen by the British version of the CIA. They removed it, and anyone who saw what they did was rounded up. And then Merlin the magician suddenly shows up as a stoned-out hippie.” The reporter of the quote, Bill Holdship, observed that Hitchcock père‘s ideas “sound as if they’d be at home in one of Hitchcock’s later songs”. Maybe. But not on Underwater Moonlight, wherein Hitchcock fils’ songwriting genuinely is surreal, delving into the erotic unconscious with wit, imagination, and something so close to genius you wouldn’t want to live on the difference.

Underwater Moonlight was the second of only two proper Soft Boys LPs from their original run, and was recorded for £600, every farthing of which was impressively stretched and exploited. It has a certain rough, blunt, rehearsal-studio feel, but it’s neither amateurish nor lo-fi. This is just one reason why it now sounds so good. Had it been slicker, it might have lost its essential eeriness. Again, Hitchcock’s timing was perfectly wrong. By then, punk’s blast-on-a-budget was fading and British music was entering an era of popular, experimental modernism and high style, neither of which was his forte, or even vaguely of interest to him.

Hitchcock has described his songwriting as “dreaming in public”, and indeed his songs often have the illogical quality of oblique dreams in which even the most devout Freudian would be pushed to find meaning. But Underwater Moonlight seems riddled with significance. The songs may try to escape it, but it hunts them out. Although everything is suggested rather than stated, you sense the residue of emotional and psychosexual nightmares which mean just a tad too much – the kind of dreams that waken you with a start and leave you wondering just what kind of sick individual you are to have that going through your mind. The same kind of sick individual as everybody else, of course. But try telling yourself that at 4:30 a.m. when this little scenario has just skipped into your reverie:

You’ve been laying eggs under my skin

Now they’re hatching out under my chin

Now there’s tiny insects showing through

And all them tiny insects look like you

The song is called ‘Kingdom Of Love’, which may or may not reveal something of Hitchcock’s then view of romance. Underwater Moonlight is full of fetid obsessions masquerading as love songs – perhaps “masquerading” is the wrong word, as love can be the most fetid of obsessions; still, you get the idea that young Robyn was not perfectly fulfilled in his interpersonal relationships. “All I want to do is be your creature,” he avows in the same song, which must be something only the best balanced of us have never wanted to say to a wished-for significant other.

The album opens with an uncharacteristic Hitchcock number, ‘I Wanna Destroy You’, which could be taken as a nod to punk, or at least a slight inclination of the head, but probably wasn’t. It’s more an exercise in harmonic screaming, a howl of hate augmented by howls of counterpoint. Plus it’s full of couplets that even the more astute punks would never have dreamt up. “A pox upon the media and everything you read,” Hitchcock snarls. “They tell you your opinions and they’re very good indeed.” Alone among the punks, Lydon might have understood, being the only one with a genuine flair for sarcasm. “And when I have destroyed you I’ll come picking at your bones/And you won’t have a single atom left to call your own.” Now that’s a pretty good threat, as threats go.

‘Positive Vibrations’ is as upbeat as its title, brisk and pretty, with some textbook raga guitar, but it feels as if things are dipping a little already. Don’t give up, because it’s around now that they really get interesting.

‘I Got The Hots’ is lustful. I mean lustful. It drips. It sweats. It reeks of secretions. And the fact that it is written in gobbledegook (a language in which Hitchcock is impressively eloquent) makes it no less filthy. It rides on the back of a slow, insistent, and lascivious guitar line, breaking off to survey the scene from above, circling and returning. It’s like being seduced by a vulture. It has the sordid, grubby quality of prime Stranglers, which it faintly resembles. It’s not nice. But what use is nice, anyway? And how they managed to get the guitars to sound like that on £600 is a continuing mystery. Those guitars are everywhere. No part of you goes unprobed.

The album’s centrepiece is the best thing Hitchcock ever did. ‘Insanely Jealous’ follows the wriggling path from resentment to psychosis with such grisly accuracy that even the humour in it serves only to tighten the cord. The track is nothing but a low, loping pulse across which pierced or scratched guitars break out like intermittent gunfire before the whole thing finally goes berserk. The menace in it is such that it’s impossible to guess whether it stems from an ardent lover or a deranged stalker – bearing in mind that in their own head, the latter sees themself as the former. It’s the sort of song that makes you feel uneasy to realise how well you understand it.

The same theme is repeated on ‘Tonight’, which follows an explicitly voyeuristic, insinuating presence: “I’m not just here for anyone’s sake… I’ll be with you wherever you are tonight.” Tonight is sinister, but clear-cut, a rival for The Police’s ‘Every Breath You Take’ as the most disquieting song on its theme. It’s almost as good as ‘Insanely Jealous’, but lacks that knife-edge ambiguity. The person who’s “insanely jealous of the people that you see/ Insanely jealous of the people that aren’t me” sounds too close for comfort, as does the song’s bleak view of love affairs: “I don’t know why the people want to meet when all they know that they’ll breed like rabbits in the end… All I hear when they embrace is just the kiss of skulls.”

Once the elliptical, early Floydish space-rock instrumental ‘You’ll Have To Go Sideways’ has whirled past (a fine Hitchcockian title, there), we find yet further abnormal goings-on in ‘Old Pervert’ – Underwater Moonlight being as direct in its titles as it is frequently abstruse in its lyrics. This off-kilter aural icepick, which wouldn’t sound altogether out of place on an album released three months later, David Bowie’s Scary Monsters (And Super Creeps), has the rare distinction of being a comic song that is actually funny, something that took Hitchcock a while to master. Of course, you might argue that there’s nothing inherently humorous about an old pervert enticing children home to inspect the contents of his fridge. And you’d be right. But a song about it can be blackly amusing, and this one is.

‘Queen Of Eyes’ is two minutes of bejewelled joy, easily the equal of any 60s West Coast snippet or Eighties Northern imitation. The closing title track may well be an ode to the tidal pull of lunar madness, or it may simply be a delightful pile of gibberish. It doesn’t pay to worry too much about these things. All you need to know is that it places the full stop on a severely under-regarded psychedelic – and at times psychotic – classic.

What became of The Soft Boys? Matthew Seligman, whose bass carries and defines ‘Insanely Jealous’ and would soon do the same for another sinister, trippy Hitchcock tour-de-force, ‘The Lizard’, was intrinsic to further great music and further great moments. He joined Thomas Dolby for the latter’s wonderful opening brace of albums, The Golden Age Of Wireless and The Flat Earth, featured on Stereo MCs’ Supernatural, and Little Earthquakes by Tori Amos, and played in David Bowie’s band at Live Aid. We lost him in April of this year, at 64, to the COVID-19 pandemic. Guitarist Kimberley Rew formed Katrina & The Waves, whose sprightly hit ‘Walking On Sunshine’ is a retro club favourite to this day. Drummer Morris Windsor teamed up with Seligman’s Soft Boys predecessor, Andy Metcalfe, in Hitchcock’s subsequent backing band, The Egyptians, with whom Hitchcock made some tremendous work in the 80s and 90s. Hitchcock went on to a solo career some moments of which rank with Underwater Moonlight for skewed brilliance: in particular, Black Snake Dîamond Röle, his first solo LP. These days he seems to be regarded, outside of his fanbase, as a cult musical comedian. This is harsh on a man who made at least two of the great British rock albums of their era and a host of other fascinating work, and whose live shows are seldom anything less than a delight. But then, he probably doesn’t mind in the least.

This article has been adapted by its author from a piece in the 1995 Melody Maker book Unknown Pleasures