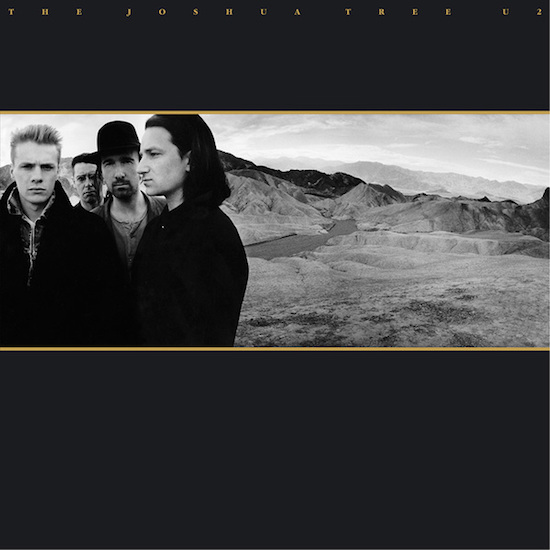

The decision U2 have taken to place The Joshua Tree at the heart of their 2017 world tour has intensified the focus on the 30th anniversary of that album’s release. This is an especially interesting point in history for such a look back to take place: and given U2’s particular and reliably contentious central position on the Venn diagram of pop and politics, the gigs are likely to be as noteworthy for the way the contemporary context is illuminated by the music of the last century as they will be for the opportunity they will offer fans to allow a personal reconnection with the past to lift some of worries of what feels like a far more complicated present.

Yet 2017 also marks a notable anniversary of another U2 album, one which may not merit a full-on world-tour of a celebration but which is certainly deserving of reappraisal and reassessment. It’s also another record that throws up some unavoidably apt parallels to the present, sufficient to make it even more deserving of another look and listen – not despite, but because of the reasons why it remains one of the group’s least regarded releases. Pop is never going to make it to the top of any fan’s list of U2’s best LPs, but that doesn’t mean its release 20 years ago this month should be ignored.

The story of The Joshua Tree is abundantly well documented, and the announcement of this year’s tour has provided an excuse to revisit the well-worn saga. It’s certainly a story well worth hearing again, from the ad-hoc non-studio recording sessions with Brian Eno and Daniel Lanois, the addition of Flood to the recording team and the uncertainty that led to second-guessing via remixes by Steve Lillywhite, to Eno coming close to wiping the tapes in a staged "accident" after umpteen days’ work on ‘Where The Streets Have No Name’ hadn’t succeeded in nailing the song. U2 have never left any stone unturned in building their legend: each LP comes wrapped in a compelling origin myth, a part of the job the group have always excelled at. They’re as aware of the power of an intriguing narrative around the music in creating a classic as they are at giving the songs an ability to beguile and involve. Yet the story of Pop‘s gestation is just as absorbing as that surrounding their more lauded releases.

Pop was clearly an attempt to fuse different past modes of working while adding something new, with Achtung Baby and Zooropa having charted a new course after The Joshua Tree led to Rattle and Hum and drove that particular style as far as it could go. To help consummate this arranged marriage of live-band rock and looped, beat-based, would-be futurism, the group reached out beyond their core team of the day. Trip hop pioneer Howie B, who had worked on the between-proper-U2-albums project Original Soundtracks 1, was in place alongside Flood. The crew that were added for Pop also numbered the diverse talents of Steve Osbourne (who had made his name producing the Happy Mondays’ Pills ‘n’ Thrills And Bellyaches), engineer Mark "Spike" Stent (who had worked on early ’90s albums by Depeche Mode, Madonna and Massive Attack as well as the Spice Girls’ debut) and Alan Moulder, best known for his mixing and engineering work on atmospherically noisy guitar records by the likes of The Jesus And Mary Chain, My Bloody Valentine and Ride. Nellee Hooper – a key figure in the early ’90s birth of what would morph later into trip hop via his work with Massive Attack and Soul II Soul (whose first album included two tracks Howie B had helped record) – was a key part in the 1995 and 1996 rehearsal-room sessions that formed the basis of Pop, though he was not involved in the recordings that were eventually released.

The album was a hit on its release in March 1997, quickly reaching Number One in over 20 countries, but it never quite seemed to capture a comparable place in fans’ hearts to previous LPs and remains among the group’s lowest-selling albums. The knives were pretty quick coming out, the group soon describing it as a flawed affair, compromised first by Larry Mullen Jr.’s absence from the earliest sessions while he was recovering from surgery on an injured shoulder, then by being rushed at the mixing stage to ensure it was on sale before the Popmart tour that began in the April. Yet there is similar disaffection within the band towards parts of The Joshua Tree, even if it’s a limited in scale and relatively muted. Adam Clayton, in his contribution to a short book included with the 20th anniversary box set, is both baffled by and derisive of the band’s failure to get ‘Where The Streets’ right: he correctly points out that the album mix, even after Edge had gone back to the tapes to remaster the LP for the box set reissue, is a frustratingly lacklustre affair. It’s a record that is destined to disappoint if used as a test when you invest in new speakers or amplifiers: it’s the sort of song where you feel sure that better equipment will finally allow the song to soar, where you’ll at last be able to sense the breathing-space between the instruments and where the rich, sonorous warmth that surely has to be there in the bass will stand revealed at last. But it never happens.

Yet Pop is the one LP in U2’s catalogue where the group’s dissatisfactions with the end product were so matched by their belief in the material that they eventually went back to the songs to try again. Half the LP has subsequently been revisited and reworked, to – in places – quite spectacular effect. The versions of ‘Discotheque’ and ‘Gone’ that appear on the 2002 The Best of 1990-2000 are superb: the former highlighting Edge’s pugilistic guitar work and foreshadowing the plainer, more exposed, raucously punk-rock sound that made ‘Vertigo’ such a dizzying high, the latter with a new vocal take from Bono that wrings every last drop of guilt and self-doubt out of one of the group’s most vulnerable songs (even as, particularly in the reworked version, it remains one of their steeliest and most indomitable sonic structures). This keeps it anchored very firmly in the same ideas that thread themselves through The Joshua Tree. It would have fit beautifully on that earlier record, a companion piece to ‘Where The Streets’ that again finds the band’s principal lyricist laying bare his discomfort with the compromises and conflicts that fame and success demand – a tricky subject to pull off without sounding like a whinging ingrate, never mind while turning those feelings into songs that soar despite it all.

Band dissatisfaction with the end product doesn’t fully explain why Pop never seemed to connect. At the time, some negativity surrounded what was interpreted as the group chasing after a new style they thought was adventurous yet was already well behind what many of their peers were trying to do. Certainly, the idea of building rock songs around breakbeats wasn’t all that revolutionary even when the initial writing sessions began in 1995, never mind when the record came out two years later. But it doesn’t seem correct to criticise the approach as the result of out-of-touch multi-millionaires desperately casting about in search of something to make them seem hip again, only to light upon a sound that only emphasised how far off the pace they’d fallen.

We can, though, excuse those who took it in that way: only a month earlier David Bowie had released Earthling, a record derided by some critics and largely ignored by fans, which found him experimenting with electronic music and drum & bass. You can understand why Pop might have felt like yet another 80s dinosaur effecting dad-dance moves on a global stage. Yet if looked at in only a very slightly different light, Pop is less U2’s embarrassing electronica album, and more their prescient big-beat record. Rather than making something that sounded dated and irrelevant by evoking the rap-rock blend Jesus Jones and EMF had hits with half a decade earlier, the record arrived on the crest of British music’s next influential wave. Pop came out a month before the Chemical Brothers’ Dig Your Own Hole, four months before The Prodigy’s The Fat Of The Land, and a year and a half before Fatboy Slim’s You’ve Come A Long Way, Baby. At its most abrasive and extreme it is as adventurous as any of those records. ‘Mofo’, for instance – one of the songs that haven’t been revisited or reworked, perhaps because the version that made it onto the album reportedly came from three different takes, each favoured by different members of the band and production team, that Flood stitched together at the last minute – is as aggressive and uncompromising in the way it sounds as it is shockingly bleak in what it has to say.

The Joshua Tree, by comparison, is a simpler record, more direct, more musically straightforward – thus easier for a wide audience to assimilate and understand. But it’s still an album rich in experimentation, its reference points ranging across the musical map from I Still Haven’t Found What I’m Looking For‘s channelling of gospel to Bullet The Blue Sky evoking Hendrix and hip hop. Crucially, it arrived at a point where a huge global audience needed something exactly like it: the band’s rise had begun in earnest with Live Aid, and they had invested plenty of time, sweat and tyre rubber in establishing themselves in the world’s biggest music marketplace. That the album ended up speaking extensively both to and about the United States undoubtedly contributed to its success both in that country and in the rest of the world (where American narratives and forms, from cinema and TV as well as music, have long been a staple). And even when it’s directly written from the band’s experiences on the road in the States – such as the rarely performed single ‘In God’s Country’, a consistently, perennially thrilling blend of euphoria and yearning – there’s a universality to the writing that means even those whose experience of the deserts of the American southwest is confined to what they might have seen on screens large or small aren’t left feeling as though this is a song that wasn’t written for (and perhaps even about) them.

Indeed, the songs on The Joshua Tree that most directly seem to deal with American landscapes or issues aren’t always as clear-cut as they seem. ‘Where The Streets’, particularly given its place as track one, side one of an album that came wrapped in Anton Corbijn’s iconic shots of the band in Death Valley, at first seems to be set beneath the same big skies of ‘In God’s Country’, but as Bono sings of a "a place, high on a desert plain, where the streets have no name," you’re inexorably drawn to the famine camps he and his wife Ali had visited in Ethiopia a couple of years earlier. Wrestling with the guilt of how an event staged to help Africa’s starving masses had enabled the band to sell more records and tickets, that visit – like the one the couple took to central America that led to them witnessing the attack described in ‘Bullet The Blue Sky’ – was undertaken not in the manner of today’s celebrity activists, who roll up with camera crews in tow to help draw attention to some catastrophe or calamity that would otherwise pass under the media’s radar, but quietly and anonymously, the couple taking their place alongside other volunteers and charity workers, the fact that it happened only coming out some time afterwards. ‘Running To Stand Still’ is famously set in the seven towers of the Ballymun flats in Dublin, but its story of addiction and desperation has a global resonance. ‘Red Hill Mining Town’ was written about the British miners’ strike of 1984/5, referencing a book by the journalist and historian Tony Parker, but it has applicability to any mining community. Rather than being an album about America, The Joshua Tree is a record that’s redolent of American music forms. Pop, by contrast, has probably as much direct focus on the US in its lyrics (‘Miami’; ‘The Playboy Mansion’), but its musical approach owes far less to blues, gospel and rock & roll (though it does, of course, rely extensively on a hip hop-derived mode of working, though that’s the one American music form that stadium-rock audiences, as a rule, tend to revile).

Yet it’s perhaps in tone and mood where we find the most abundant evidence to help explain the two albums’ differing places in the hearts of both band and fans. The Joshua Tree is a record that takes us to some dark, dark places – cowering underneath those air strikes, trapped by circumstance among the seven towers, or, in ‘Exit’, inside the mind of a murderer – but it always retains a sense of hope. The protagonists of ‘Running To Stand Still’ may not get there, but they’re trying to find a way out of their troubles; love (or faith; or both) may have been stretched to beyond breaking point in ‘With Or Without You’ but the singer is telling the subject of his adoration that as bad as things have got, trying to live apart won’t work either; even in ‘Mothers Of The Disappeared’ there is a sense that, while those stolen away will never return, the junta that took them will collapse and the dead will be avenged.

Pop is cut from very different cloth. It’s not that the U2 who made The Joshua Tree no longer existed, nor even that the scorched-earth approach they’d taken after that album’s success (Achtung Baby had famously been called, by Bono, "the sound of four men chopping down The Joshua Tree") had meant they were deliberately turning their back on every element of what had made it work. Rather, Pop is an album made by people who could never again entirely convince if they were to try to recapture that wide-eyed optimism with which they toured the States in the mid-80s and which was the fuel they burned during the writing and recording of their biggest-selling album. Despite the lightness, colour and frothy disposability implied by that title and some of the songs’ sonic packaging, Pop is a pretty dark, heavy record.

At the risk of fixating on the obvious, it’s also worth stressing that Pop comes from a very different time and place. It’s an album that arrived after Achtung Baby and Zooropa, records that no longer looked to America but had very deliberately been built in, and in some ways out of, the new Europe that had begun to take shape following the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989. More importantly, it came after the disintegration of Yugoslavia and with the return of death camps to Europe decades after the supposedly resurgent and renewed continent had promised itself: "never again". The album may not have directly referenced that conflict – the staggering Original Soundtracks 1 song ‘Miss Sarajevo’ surely saying everything that U2 felt they had that could be said – but these senses, both of long-held certainties upended and of hope remaining stubbornly beyond reach, are never too far away, even in the record’s most apparently uncomplicated and upbeat moments. Take ‘Discotheque’, and its ostensible subject of a music fan losing themselves in the sounds they love out on the dancefloor: at its heart, nothing is as it first seems. "You can reach, but you can’t grab it," the song begins; "You can’t hold it, control it, you can’t grab it". The person Bono is singing to "want[s] to be the song that you hear in your head," but it doesn’t work – so in the end, he or she has to "take what you can get/’cos it’s all that you can find." That would never have been the advice offered to any of the characters who inhabit The Joshua Tree‘s songs. Even before September 2001, this had become a bleaker, colder world: Pop has little room for the optimism The Joshua Tree so carefully and diligently mined.

Some of the discussion ahead of this year’s tour has centred on how the songs from The Joshua Tree will resonate in today’s divided America. When the record first came out, Bono hadn’t done enough glad-handing with politicians to have become the hate figure to so many that he is today; even Pop predates that, arriving weeks before Tony Blair won his first UK election and six years before the second Iraq war. (Let’s put to one side for now the fact that his decision – to use the access his unusual level of celebrity gave him, regardless of how much damage the compromises required caused to his own and his band’s public image – was uncommonly brave.) Attention is already starting to focus on to what degree – or even whether – he will speak against Donald Trump during the shows: yet even if the inveterate campaigner and instinctive bridge-builder feels he needs to keep himself on non-adversarial terms with the present occupant of the White House, it will be difficult to hear a song like ‘I Still Haven’t Found What I’m Looking For’ as anything other than critical of a regime that plans to build walls rather than tear them down. But it would be interesting, too, if the shows found some room on their set lists for the very different group of songs U2 released a decade later. The very things that make Pop a record that fans find difficult to love are precisely the elements that make these strange, complicated times far better ones in which to listen to them again and try to interpret them anew.