For a long time, I didn’t listen to it. It was like a house you’d lived in, or your old school. Somewhere that for a while, an eventful and formative while, had seemed like the centre of the world. Then you move on, and other things happen. You lead a different life, become a different person. When you do go back, it’s uncanny. In the Freudian sense: altogether familiar, altogether strange. It all seems so much smaller now, a place a whole other life occurred.

It wasn’t just me. It’s hard to recall, in our atomised era, but 25 years ago it was possible for an entire segment of culture to not only like, or love, but to inhabit an act. If you were one kind of music fan, Oasis were where you lived. (At that point, it sometimes felt like Oasis were where the whole country lived, whether it wanted to or not.) If you were another, you were Tricky’s tenants. This may sound hyperbolic. It isn’t. That truly was how it felt. It didn’t mean you couldn’t enjoy both – I did; so much so, in the case of Oasis, that I never forgave them for plodding again and again along the same path they briefly lit up with fiery footprints, until it was hollowed into a rut.

You couldn’t accuse Tricky of that. The trouble was, others did the plodding for him. The pre-release tape of Maxinquaye with which, and within which, I spent the turn of the old year and the start of the next was so astonishingly new I had to keep replaying it just to check I hadn’t fooled myself into my state of stupefaction. It would have the same effect across the country when it was released. Within a year or so, every other winsome college girl and her bleeping boyfriend would have formed a duo, turning out by the yard records which were to Maxinquaye what crabsticks are to crab.

Two years later, after he had released the awkward, bristling Pre-Millennium Tension, I asked Tricky if that album was meant to be uncopiable. "It is. I’m forced away from what I would call my music. I can’t do another thing like Maxinquaye. I can’t even listen to it. I find it hard to do it live because, for me, Maxinquaye is a shit album, as in now it sounds just like hundreds of other shit albums out there. But if people didn’t go out and copy it, I might have done another three or four Maxinquayes. Which is terrible."

It may be that no great album represented so brief a phase in its creator’s career, because no great album was both so immediately acknowledged, and so eminently imitable with so few resources. That might be another reason why I didn’t listen to it for so long. Perhaps, like Tricky himself, all I could hear was the homeopathic coffee-table versions of it.

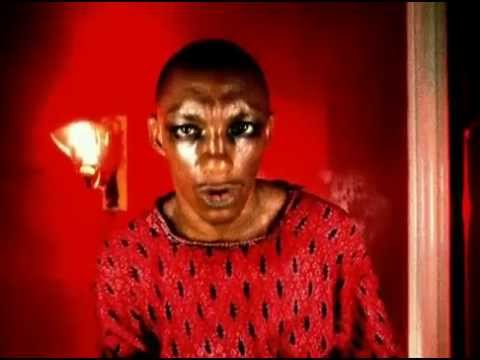

What did it sound like before that happened? I see I described it as, "Sibilant, tenacious," and – that word again – "uncanny." I predicted it would, "fuck with people’s ideas of what pop music is and what it can do." Which I suppose, given how widely it was mimicked, it must have done. Tricky, I claimed, "writes songs that aren’t songs, lyrics that trail at the edge of recognition, music that bypasses reason and heads straight for the senses, sounds that you can smell and taste and feel against your skin. He doesn’t sing, or even rap in any recognised way … [he is] so elusive that often his own performances seem disguised – mixed down, behind or to the side of Martina, furtive."

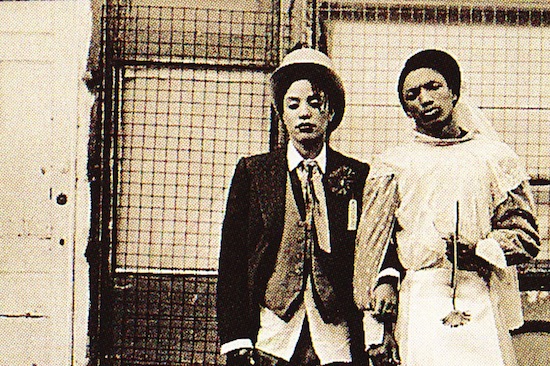

Martina Topley-Bird, then 19, was his girlfriend and accomplice, and while I gave her a fair bit of credit for her contribution, I don’t think I or anyone else gave her enough. I didn’t mistake her for a sock puppet, but listening back now, I hear how strongly her vocals defined the album. Again, her own horde of imitators diluted that sense after the fact, but I hadn’t heard them then. I think I assumed she was filling in for Tricky himself, and she was, but hindsight reveals what a vital task that was. There was such instinctive art in the way she performed it, such unpolished poise, that it would surely have been a very different and probably much lesser record had anyone else – and in particular anyone more experienced, professional and artful – taken that role.

What does it sound like today? It really does all seem so much smaller now. But that’s no disappointment. Stripped almost instantly by sincere flattery of its power to surprise with its sounds and ideas, it has acquired over the years the power to surprise by how tight, compact and catchy it is. Knocked sideways by its originality, I’m not sure I realised at the time it is also a blinding pop album.

Maxinquaye is around an hour long and the first three-quarters of that is left-field bubblegum gold. It opens with a cover version, of sorts: ‘Overcome’, in which Tricky remakes his own Massive Attack number, ‘Karmacoma’, as a thick, unquiet fever dream – and an almost cubist vision of a moment in time that encompasses within the same frame a couple walking through quiet suburbs as the Gulf War rages three thousand miles away. It’s one of two numbers not first heard on Maxinquaye, the other being ‘Black Steel’, the ingenious rock version of Public Enemy’s ‘Black Steel In The Hour Of Chaos’. I’ve met a fair few people who know the song only from here, and for whom the original, when they seek it out, is as startling as the Maxinquaye take was then. Between them comes ‘Ponderosa’, dragging its clanking chains like Marley’s ghost. (Jacob, not Bob. There was an awful lot of Bobness bobbing about just then, but Tricky had stranger fish to fry; retrieved via submersible from the depths where weird things swim.)

I notice only now how much ‘Ponderosa’ echoes Tom Waits. Returning to Maxinquaye with ears tempered by time, and with the shock of its newness having long since receded, its sources are easier to spot. Which makes it no less remarkable. Twenty-five years ago, it was possible to believe you’d never heard anything like it before; when of course, what you’d never heard before was this particular adaptation. Which is the beauty and joy of the new – not that it’s without precedent, but that it feels that way.

‘Hell Is Round The Corner’, for instance, didn’t just revolve upon an Isaac Hayes loop, but upon the same loop (from ‘Ike’s Rap II’) Portishead had already used on the exquisite ‘Glory Box’. It’s a measure of each act’s invention that each track seemed fresh and entire of itself. Everybody concerned may have tried to distance themselves from the notion of a Bristol scene – "I was supposed to have invented trip hop, and I will fucking deny having anything to do with it," said Tricky, with understandable venom – but there was certainly a Bristol sound, and we know now it constituted British indie-pop’s last grand sub-cultural flourish before Britpop’s dead hand fell upon it.

"If I was in a band," one usually electronics-averse colleague said of Maxinquaye, "and I heard this, I’d probably think, why am I even bothering?" ‘Pumpkin’ was likely the point at which all those soon-to-be trip-hoppers, who must have thus far listened with a combination of awe and despair, thought to themselves, "Hang on, we could have a go at this." Five tracks in, it’s the first thing on there that sounds straightforward enough to be attainable. A steady beat, a climbing tune, a torchy vocal… and Tricky growling allusive filth beneath it, but that’s the bit they usually decided they could do without. Inevitably, if you had to choose between it and the entire catalogue of things that resemble it, you wouldn’t need to blink, let alone think about it.

It probably didn’t happen that way, though, because the soon-to-be trip-hoppers had a head start with ‘Aftermath’, which thirteen months previously had been Tricky’s first release, causing a multitude of ears to prick up and jaws to drop. That shuffling beat, that slumberous, claustrophobic atmosphere, Martina’s voice flitting through it, deadpan and spectral. Only a year after Jacques Derrida proposed the idea of hauntology, Tricky and Martina created an exemplary musical manifestation of it. As debut singles go, it’s up there with the greatest of them – ‘Virginia Plain’, ‘Anarchy In The U.K.’, name your own favourite – as both a statement of intent and a gobsmacking thing. Something that one moment wasn’t there and the next moment was, and made life feel different because of it. "Just when I thought I could not be stopped," murmurs Tricky at the end of the longer album version, revealing another apt and, in hindsight, unsurprising source – ‘Ghosts’, by Japan.

‘Abbaon Fat Tracks is pure sleaze’; the sly, whirring ‘Brand New You’re Retro’, a semi-parodic and wholly brilliant rap throwdown. ‘Suffocated Love’, which lives up to its title, is yet another blueprint much consulted and never bettered. Because, how could it be? The only way you’d have the imagination to improve on it was to be the person who thought of it, and that person never tried. Then there’s ‘You Don’t’, which stands alongside ‘The Rhythm Divine’ and ‘History Repeating’ as a magnificent, melodramatic Shirley Bassey electro track, despite Shirley Bassey not appearing on it; Icelandic singer Ragga fills in neatly.

Again, I’m struck by how songs which then seemed to spill their contents over their brims now seem so spare and tidy. I’d say there’s not an ounce of fat on Maxinquaye, and it would be true but for the final two tracks, ‘Strugglin” and ‘Feed Me’, which aren’t bad by any measure. They’re the most avant-garde and overtly "difficult" things on the album, and in being so they emphasise just what corking pop tunes are the ten tracks which precede them.

Maxinquaye was an album of its time largely because it made its time what it was. For better or for worse. Out of its time, it belongs to a category beyond that of mere genre. It’s one of those albums whose radicalism is matched by its brilliant immediacy, an inescapable barrage of pleasure bombs whose revolutionary impact is succeeded by an undimmed afterlife. Revolver, Highway 61 Revisited, Supa Dupa Fly, Technique, Maxinquaye. Argue the toss about their relative greatness if you care to; still, you understand the type. You don’t get a lot of those lately, not because nobody is capable of producing them, but because our pop culture is seldom cohesive enough to recognise them. Sic transit gloria Tricky, and all his kind.

David Bennun’s original Melody Maker interviews with Tricky can be found here