“Bono could have been a president or prime minister standing on his head. He had an absolutely natural gift for politicking, was great with people, very smart and an inspirational speaker. I spent a long time wondering what made him so good at what he did.”

Tony Blair, A Journey, 2010

“What I admire the most about Tony Blair is that despite all accusations of a slick PR machine, spin doctoring and the like, he has almost all of the time exposed himself to bad press and outcry for doing the things he believed in.“

Bono, The Sun, 2007

That Tony Blair and Bono should hold each other in such mutual high regard is perhaps not surprising: both rose through the ranks of their respective milieu with a resolute sense of self assurance, surrounded by a solid team of foot soldiers who believed in them, immersed in the history of those who had gone before them, learning from those around them. They reached the most elevated heights of their professions where, celebrated by those who had helped them achieve their goals, and buoyed by the certainty of others that they could improve our world, they were held in admiration by an audience who bathed in a joyful, communal sense of better times ahead. For a while they fulfilled such hopes, but the pure oxygen of their rarefied altitudes made them giddy: they lost touch with the qualities that had put them at the top, and stopped listening. Their growing delusions of grandeur gradually led them to make poor – or at least unpopular – decisions, and people lost faith in their pronouncements, feeling increasingly that they’d been cheated, before, slowly, peeling away from these one-time saviours. Some remained faithful to them – for honourable reasons, or through pure obstinacy, even thanks to sheer stupidity – but most stepped back, shaking their heads with incredulity. These former redeemers might still hold notional, ceremonial positions, but they were deluded if they felt many people cared about them.

Nowadays, for a lot of folk, to ridicule both Tony Blair and Bono is a kneejerk reaction. Both opine vainly upon the important topics of the day, ignoring the sentiments of those around them, overconfident in their convictions that they know more than others. They’re deaf to the criticisms heaped upon them because, they presumably reason, these are merely evidence that, as the Bible taught them, “A prophet is not without honour, but in his own country”. Just as Tony Blair, a Middle East ‘peace’ envoy, continues to insist loudly that ground troops are the only solution to problems that he, as much as anyone, provoked with similar actions, so U2, in an extraordinary act of hubris, recently inflicted their latest album – Songs Of Innocence, with …Experience due next year, and undoubtedly hard won – upon a world in which sales of their previous record are said to have been the lowest the band had achieved since 1991’s Achtung Baby.

If Blair’s words had tumbled from the mouth of someone more wiling to accept responsibility for their mistakes, they might have held some credence. Instead of dismissing his thoughts, we might have welcomed the expression of what we once valued enough to consider his wisdom. His were considerations born of experience – that word again – and worthy of debate, whether anyone likes to admit it or not. Similarly, had another band – less flush with whatever currency U2 use to pay their meagre taxes – heroically managed to persuade the world’s most valuable company to share their latest work with a little more humility, the action might have been greeted unquestioningly as innovative generosity. But the narcissistic assumption that we’d be grateful for the invasion of our private music collections was a miscalculation of vast proportions. The band was paid millions, we were ostensibly hacked, and Apple were soon forced to provide instructions as to how we might dismantle this particular atomic bomb to rid our computers of the record for ever. Rather than go viral, U2 had become a virus. Their mistake, like Blair’s, was not to stop wondering what other people might think of them. It was instead not to care.

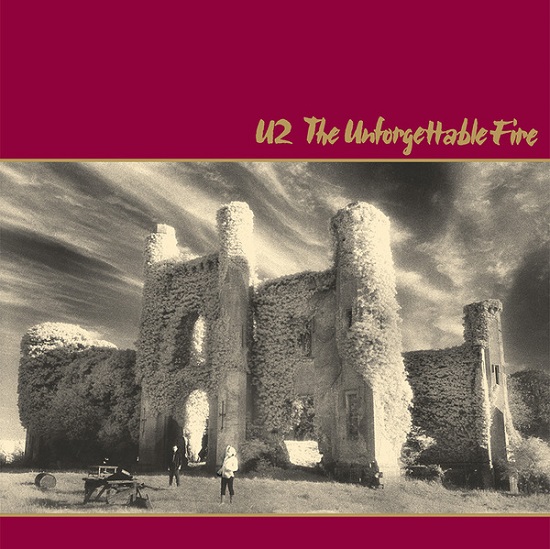

1984’s The Unforgettable Fire was U2’s equivalent of Blair’s 1997 landslide victory. There were, of course, those who doubted the Irish quartet’s embrace of a new, more ambitious approach, just as, some thirteen years after U2’s major international breakthrough, there were folk in the 241 of 659 seats that Labour hadn’t won whose hearts sank as the national results confirmed the new government. But the majority voice that greeted both was one of celebration. However much Blair’s and U2’s actions may have retrospectively diminished grounds for such sentiments, they seemed valid at the time: promises were not only being made, but apparently fulfilled. There was, at last, reason for hope. It was ill founded, perhaps, built upon optimism rather than evidence, but it felt good.

Thirty years on from its release, The Unforgettable Fire is ripe for re-evaluation. To increase sales of their back catalogue was, after all, allegedly one of the motivating forces behind their recent, ill-conceived partnership with Apple. So, as Tony Blair himself said in 2003, on the eve of the invasion of Iraq, “Let the day-to-day judgments come and go: be prepared to be judged by history.” Likewise, Bono, was it not you that once said, “History, like God, is watching what we do…”?

U2’s fourth album came less than 18 months after their platinum selling War, which had reached the top of the UK charts and peaked at number 12 in the US. A rough and ready collection that included ‘Sunday Bloody Sunday’, ‘New Year’s Day’ and ‘Two Hearts Beat As One’, it was an unlikely chart-topper – if only for one week – thanks to Steve Lillywhite’s peculiarly primitive production and its stripped back arrangements. Its rallying cries were simple and effective, however, and earned them stadium size audiences, as captured on the late 1983 mini-album, Under A Blood Red Sky, an audio companion to a concert film which had been recorded at the 9,450 capacity Red Rocks Amphitheatre in Colorado a few months earlier that year. (The album itself also drew on tapes of shows in Boston, USA and Sankt Goarshausen, Germany). This had revealed to those in the world who’d not yet seen U2 play that they were an often lively, communicative band fuelled by righteous, if not entirely imaginative, indignation: there was an apparent – certainly credible – spontaneity and rawness to their performances, a remnant, no doubt, of their punk roots. Bono, too, was charismatic and passionate, his energetic breathlessness believable, and the crowd’s hysteria unequivocal.

Listening back now – admittedly with the benefit of the purported sophistication that age brings, the hindsight acquired from a series of progressively more turgid releases, and the recognition that Bono might defend any cause that brought with it a spotlight, except that of suicidal Chinese factory workers – Under A Blood Red Sky seems sometimes clumsy, a harbinger of the glutinous stadium gestures that would follow further down the line. Bono is at times an overenthusiastic frontman, already a little too fond of the sound of his own voice, while his band is occasionally heavy-handed and oddly – almost endearingly – naïve. (Listen to Adam Clayton’s bass solo on ’11 O’Clock Tick Tock’ and try not to think of Spinal Tap’s ‘Jazz Odyssey’.) Nevertheless, you’d struggle to deny the fire in the belly of ‘The Electric Co.’ – The Edge has rarely sounded more exciting or more spirited – and if there was a more powerful, poignant way to end a show than their adaption of Psalm 40, I’d certainly not heard it at the age of 13. The sound of the audience singing those final words to ’40’ – “How long… to sing this song?” – gave me goose bumps. U2 were the band that made arenas seem like the greatest venues on the planet.

Their response to this growing global appeal was surprising. To their credit, it was fuelled by their fears for what they might become if they were to pursue the obvious route ahead of them. Seen for what it is, The Unforgettable Fire‘s critical and commercial success is a welcome reminder that – back then, at least – musicians could challenge not only themselves but also their audience, and still come out on top. They might have gone further, too: among the producers considered were Conny Plank, who’d worked with Can and Kraftwerk, and Jimmy Iovine. The latter had admittedly helmed Meatloaf’s Bat Out Of Hell, but he’d also been behind the desk for Patti Smith’s Easter and Bruce Springsteen’s Born To Run. In fact, he’d already worked with the band on Under A Blood Red Sky. Arguably, it showed.

In the end, they hooked up with Brian Eno and Daniel Lanois, who was promoted to co-producer from his position as Eno’s engineer because the former Roxy Music member initially felt that the opportunity was not right for his own CV. The Edge, it’s said, was Eno’s chief advocate, but it was no doubt the same persuasive qualities in Bono that Tony Blair would later praise which convinced the producer to come on board: the man has always talked a good talk, and U2 had, in many ways, never been a more compelling unit. Of course, the pioneer of ambient music and his budding sidekick were an unexpected choice, one that Island Records were initially unhappy to endorse, but it proved a sharp decision. Indeed, so successful was it that this would be the first of six studio albums upon which Eno and U2 would collaborate, while Lanois would be involved in five.

Together, they used The Unforgettable Fire to help reinvent the band’s sound, and, in so doing, consolidates U2’s position as one of the world’s biggest acts. They did it so conclusively that Bono would only have to pluck women out of the Live Aid crowd nine months later to confirm his role as new messiah. To be fair, while this gesture – made amid an interminable medley of songs shoehorned into ‘Bad’ – may have represented the moment Bono drank his own Kool-Aid, it was also a surprisingly touching moment of intimacy that stands out as one of Live Aid‘s most memorable moments. He was always “great with people”.

Though it’s true that even U2’s be-shaded singer has expressed his dissatisfaction with parts of The Unforgettable Fire, it’s rather sad that one feels almost duty bound to defend one’s belief in it purely because it helped spawn a monster. To some, this will be heresy, but the album is frequently tremendous, if – like everything U2 do – fallible. Its horizons are so broad, its drama so potent, its ambitions so vaulting – so much so that the band would eventually “o’erleap itself”, and there we go, making excuses again – that, at least for those who were around at the time, it’s hard to resist.

Inevitably, though, it’s impossible to shake off the sense that Eno’s and Lanois’ guiding hands are responsible for The Unforgettable Fire‘s greatest qualities. The more one examines it, the easier it is to dissect and belittle the band’s contributions and instead applaud the men behind the mixing console. Their identity is subtly stamped throughout the record, helping to ensure that – to paraphrase Bono in the album’s opening track – the earth moves beyond the dream landscape. Where before the band had played as a straightforward four piece, rarely adding embellishments, tied to the principle that their music must remain authentic – they’d always rejected the idea of performing songs that couldn’t be replicated live – now they embraced the technical possibilities of the studio. Arrangements were fleshed out with atmospheric enhancements, first in the grand surroundings of Slane Castle, and, later, at Dublin’s Windmill Studios, and it was this newfound depth to their sound that was so seductive. U2 now sounded like a band that could not only straddle the globe but also see beyond it.

This was ‘Big Music’, as Mike Scott would brand his own attempts at this epic style on a track taken from A Pagan Place, The Waterboys’ second album, released a few months before U2’s. It strove to encompass grand themes and encapsulate them in a matching sound. But where Scott’s ambitions would reach their zenith a year later on This Is The Sea with what he described in his autobiography as a “spiritual seeker vision” – his lyrics inspired by the likes of C.S. Lewis and William Blake – U2 would rely more heavily on musical smudging and verbal ambiguity, Bono’s texts lent most weight by their sumptuous backing and lofty titles like ‘Elvis Presley And America’. Sure, the urge driving the band was palpable, but Eno’s smoke and mirrors did much to mask the shortcomings of the songs themselves.

Still, there’s little point disputing that there’s plenty of excitement on offer, and that’s audible right from the start, with ‘A Sort Of Homecoming’ briefly teasing and stuttering like an engine firing before The Edge’s guitars begin to chime, whirr and ricochet. Larry Mullen Jr.’s drums rattle and shudder beneath Bono’s impassioned delivery, the closest to what we might have expected from the band that had made War. With ‘Pride (In The Name Of Love)’, they carved out something much more instantly distinctive, The Edge’s guitar now blurry, its delay pedal churn soon to become his trademark. Now considered one of the band’s most famous tracks – and, damned with faint praise, once named the 378th Greatest Song of All Time by Rolling Stone – its indisputable anthemic quality lies as much in the extravagant manner that Bono raises his voice for the chorus as the riff that lies at its heart, not to mention Mullen Jr.’s inventive use of cymbal crashes in the bridge. That its lyrics were focussed on the assassination of Martin Luther King – allowing like-minded liberals to feel that this was more than mere pop music, and helping propel it to number three in the UK charts – did no harm either, and Bono returned to the theme on the album’s closing track, ‘M.L.K.’, underlining his undeniable sincerity: “Sleep, sleep tonight/ And may your dreams be realised.”

There were plenty more thrills, too: ‘Wire’ set off at breakneck speed, The Edge now seemingly cut and pasted throughout the track, little flurries of chords – each sparkling with effects, as though a whole orchestra were present – layered on top of one another, lined up after one another, bursting forth out of the verses. Clayton, too, seemed interested in more than merely underpinning the song, and ‘Indian Summer Sky’ mirrored ‘Wire”s mood closely, Bono again reaching for the skies, added tension coming from the song’s briefly subdued bridge. Restraint was equally manifest in ‘Bad’, a lengthy version of which soundtracked Bono’s excursion into the Wembley crowd the following summer. Here they let the song breathe, building it so that it swelled at a cautious pace, Bono leading it like a pied piper towards a rousing climax. A similarly subtle approach distinguished the album’s title track, with peals of guitar resonating through the song’s verses. These were delivered in a sometimes whisper, sometimes snarl, before a series of dramatic tangents: a romantic, windswept, unexpected third act to an already almost immaculate concept.

There was even outright experimentation – by U2’s standards, anyway – in the form of the record’s two central tracks, ‘Promenade’ and ‘4th Of July’. Bono’s growing knack of letting his voice soar at the most appropriate, heart-tugging moments is especially prominent on the former, where he wails poetically of how “And I, like a firework, explode/ Roman candle, lightning, lights up the sky”, while the instrumental that followed boasted little more than two minutes of bass, guitar and the kind of ambient echoes found on Eno’s 1983 album, Apollo: Atmospheres And Soundtracks. In fact, such sonic tricks were concealed within most tracks, sometimes suggestive of an almost symphonic profundity to the arrangements, at others – such as on ‘Elvis Presley And America’, prototype shoegazing on which Bono sounds like he’s singing through a velvet curtain – merely displaying a willingness to try something new on for size. Without these details to oil the machinery and make its surfaces glisten, one suspects, the album might have felt comparatively rusty and lifeless, a fall-back to the mildly claustrophobic, shallower fare in which they’d formerly traded.

What these features also did was distract from Bono’s lyrics. They weren’t, it has to be said, always poor: indeed, at times he stumbled upon striking images – “See faces ploughed like fields that once gave no resistance” (‘A Sort Of Homecoming’) – and intriguing assonance: “Innocent, and in a sense I am/ Guilty of the crime that’s now in hand” (‘Wire’). Elsewhere, his phrases were at least impressionistic, deceptively suggestive, when grasped in isolation, of a more poetic whole: “Carnival, the wheels fly and the colours spin through alcohol/ Red wine that punctures the skin” (‘The Unforgettable Fire’); “True colours fly in blue and black/ Blue silken sky and burning flag” (‘Bad’); “If the thunder cloud passes rain/ So let it rain” (‘M.L.K.’).

At other times, however, his lyrics seemed unmoored from any genuine meaning, disembodied words searching for significance. If their essence was intended to be cryptic – as indeed it might have been, given the band’s concerns about their potential for sloganeering, especially in the wake of the controversial reception to ‘Sunday Bloody Sunday’ (which, Bono emphatically insisted on Under A Blood Red Sky, was “not a rebel song”) – then they fell foul of the man once nicknamed Steinhegvanhuysenolegbangbangbang’s oft-oozing sincerity. Just as it’s hard to believe that his Band Aid contribution, “Tonight thank God it’s them instead of you”, was meant to be ironic, so it’s difficult to imagine that he thought of any of his lines here as anything other than eloquently solemn. No matter that he’s singing “See say you’re sad and reach by/ So say you’re sad above beside” (‘Elvis Presley And America’): you can tell he means it, man. That’s despite a unique sense of tenses and grammar that gives rise to lines like, “One man come in the name of love/ One man come and go/ One man come he to justify/ One man to overthrow…” (‘Pride’). What, one wonders, would it have taken to tidy up that first verse a smidgeon so it sounded less pidgin? (Laurie Anderson was right: language, like U2, is a virus.) To be fair, Bono has since stated that he felt his words had been rushed, and some – like ‘Pride”s, he claimed – even remained unfinished. “As a lyric it’s daft,” he told Rolling Stone in 2005. “No, not daft. It’s just not deft. It’s a missed opportunity. I even get the time of Dr. King’s assassination wrong. I said, ‘Early morning, April 4.’ It was early evening.”

On ‘Promenade’, in addition, he sings bafflingly of “Earth, sky, scenery/ Is she coming back again?/ Men of straw, snooker hall/ Words that build or destroy” before he’s politely taken to one side by uniformed men, rambling like some Sunday morning drunk as he’s led away: “Slide show, seaside town, Coca-Cola, football, radio, radio, radio…” In fact, reading his doggerel – after thirty years of giving it the benefit of the doubt and not actually investigating it – is simultaneously enlightening and perplexing: though ‘Wire”s couplet, “In I come and out you go you get/ Here we are again now, place your bets” could almost be Burroughs, it’s not, and ‘Elvis Presley And America”s lyrics (reproduced here verbatim from U2’s own website) are similarly obtuse: “You know ‘S’ ‘O’ ‘N’ ‘G’, why/ You’re going go join to God/ You know ‘S’ ‘O’ ‘N’ ‘G’, why/ Give away some him no lie/ Give away some my de day no…” Bono has since admitted the vocals were recorded in five minutes. The song is six and a half minutes long.

Make no mistake, there’s no need to ridicule everything Bono sings, but it’s no wonder he swallows his words as often as he does. In fact, at one stage on ‘Wire’ – which he’s stated is a song about drug addiction – he grunts, groans, huffs and puffs as though he’s physically wrestling with himself to stop another mouth turd launching from between his lips with the grace and éclat of a SCUD missile. Since he’s just hissed “Kiss me!” like a punctured blow-up sex doll, this must be one of the least romantic moments in the history of rock & roll. Furthermore, this apparent – if subconscious – self-censorship makes it all the more strange that he chose to articulate the adolescent, unintentionally funny lingual fumblings of ‘Bad’ so clearly: “This desperation, dislocation/ Separation, condemnation/ Revelation, in temptation/ Isolation, desolation…” Where were ‘flatulation’, ‘flagellation’ and ‘pandiculation’ when you needed them? You’d nail him to a cross for lines like those if it weren’t something he’d so clearly enjoy.

But, for all this snarking and sneering, The Unforgettable Fire nonetheless holds up as one of the finer albums of its time. Such is its bravado and energy that its weaknesses are largely overcome. Bono’s legitimate moments of thunder are shared by The Edge’s crafty sleights of hand – his techniques were, at the time, as revolutionary to some as Kevin Shields’ would soon seem to others – as well as their producers’ instinctive nous. Many of those muddled lyrics remained excused, even disregarded, their content enigmatic enough to provide cover behind which the band could hide, while The Edge’s increasing status as a guitar hero provided further diversion from the record’s frailties. Eno and Lanois had also decorated it just enough to suggest that it was the band’s magic they were enabling: only later would the significance of their contributions become more recognisable through their repetition elsewhere. The record even helped Eno define himself, by proving that his techniques could be applied to the most unlikely of subjects: a sometimes ponderous band reaching beyond their abilities, but with the imagination to dream they could do it. That this led Coldplay to him almost two decades on was probably inevitable, but it shouldn’t be held against an album that ascends despite its earthly shackles.

Closer inspection may suggest that The Unforgettable Fire is merely “a tale told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, signifying nothing”, but such derision is partially inspired by the cruel pleasure many enjoy these days in mocking Bono. Perhaps he’s an idiot – few of us have ever met him, so we can’t really be sure, though the fact that he’s small enough to hold in the palm of your hand suggests some kind of Napoleon/Sarkozy complex might be at work. The record may be full of sound and fury, too: arguably, that’s one of its strengths. (A lack of sound, on the other hand, might benefit their more recent releases.) But it definitely adds up to more than nothing – much more than nothing.

Like Blair’s early 21st century actions, The Unforgettable Fire was almost entirely convincing at the time, and, unlike Blair’s efforts, it never killed anyone. In fact, it’s still possible even to enjoy it. There was, after all, something commendable in this bluster and bombast; in this desire to outreach oneself, in this faith that the landscape we knew – but perhaps quietly resented – could be changed. History might judge The Unforgettable Fire hollow, but that’s partially because, like Blair’s policies, it’s been drained of its values by subsequent events. At least back then, they – and many of us – believed in what they were doing. How our dreams can be crushed.

“Mine is the first generation able to contemplate the possibility that we may live our entire lives without going to war or sending our children to war.”

Tony Blair, NATO summit speech, 1997

“The right to be irresponsible and stupid is something I hold very dear. And luckily it is something I do well.”

Bono, Q, 2001