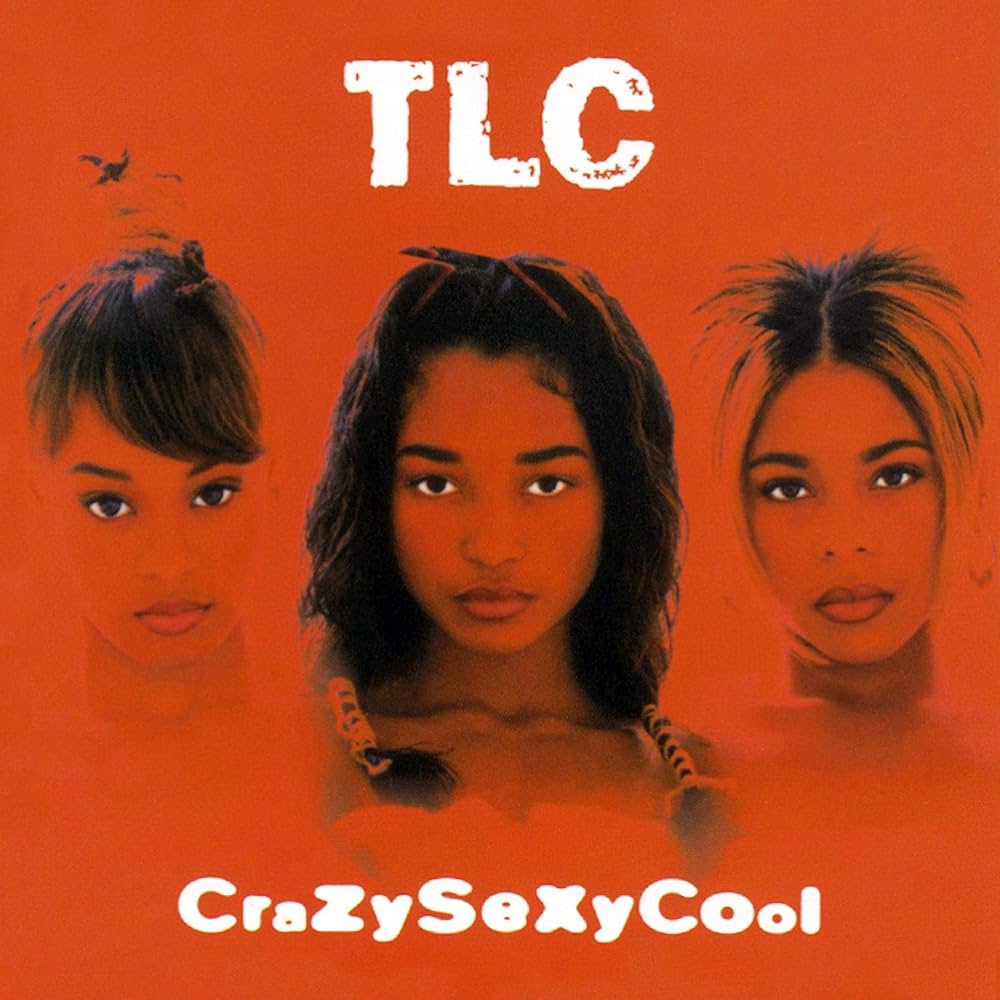

CrazySexyCool is the record that destroyed the Auteur Theory in pop.

The second album by TLC is a magnesium-bright, diamond-hard, battleship-durable masterpiece, as all civilised people agree… or, at least, they do now (we’ll come to that in due course). It’s straight-up one of the greatest albums of the 90s, and a landmark in Black American pop. But a masterpiece, ex vi termini, requires a master, does it not?

It’s an enduring received rockist assumption that great pop – especially great pop by women – must have a male genius lurking somewhere in the shadows (a Phil Spector or a Brian Higgins), or a duo thereof (Chinn & Chapman, Rodgers & Edwards, Jam & Lewis) or even a trio (Holland-Dozier-Holland, Stock Aitken Waterman).

To these maestros, svengalis and impresarios, most of the intentionality behind the final work is credited by critics (and even many fans), while the stars fronting the thing, usually female, are implicitly pieces of disposable and interchangeable window-dressing. There is a parallel in cinema, dating back to the 1960s. In 1962 Andrew Sarris, the New York Times film writer, developed the highly influential Auteur Theory of filmmaking, whose three central components were: 1) Technical Competence, 2) Distinguishable Personality, and 3) Interior Meaning. When transposed to pop, it’s a theory which favours said myth of male genius: the idea that a man, or two or three men, who know their way around the faders, are the ones whose mark is to be found on the finished product, and that any cohesive mood or message within that product should be ascribed to them, not the disposable canaries behind the microphone.

Of course, there are dozens of cases where the Auteur Theory stands up tall, monolithic and marble-confident. A close analysis of CrazySexyCool, however, is the lens through which the whole edifice begins to fracture and fall apart.

That isn’t to say that powerful male producers weren’t involved. If anything, too many of them were, which is where the Auteur idea comes a cropper. The credits on the record are as convoluted as your average modern Marvel Universe superhero movie. For a start, it has no fewer than three Executive Producers, ticking the ‘technical competence’ box.

Two of them were relative old-timers. Antonio ‘LA’ Reid, 38 when CrazySexyCool came out, and Kenneth ‘Babyface’ Edmonds, 35, were funk veterans who had founded the LaFace label in 1989, on which the album was released. Their back catalogue, as a production/songwriting team, included plenty of hits you’d recognise: ‘End Of The Road’ by Boyz II Men, ‘Every Little Step’ and ‘Humpin’ Around’ by Bobby Brown, ‘Superwoman’ by Karyn White, ‘I’m Your Baby Tonight’ and ‘Queen Of The Night’ by Whitney Houston. Decent enough, but nothing mindblowing, suggesting them to be something more than journeymen, but something less than geniuses. In the post-CrazySexyCool era they would increasingly slap their names across their artists’ albums as Exec Prods with little evident hands-on involvement beyond giving a project the green light. One thing for which LA & Babyface clearly had a talent, however, was spotting other talent. Which is where the third Executive Producer comes in.

Dallas Austin, a 23-year-old from TLC’s home town of Altanta, Georgia, was a keyboard whizzkid who benefited from being in the right place at the right time, for example the roller-skating rink where TLC’s T-Boz was a customer and where a studio had been built by production duo Organized Noize. On his rise through the ranks as a producer, Austin had scored a big hit with the aforementioned Boyz II Men’s debut Cooleyhighharmony when barely out of his teens. And, if we look at his post-CrazySexyCool CV, it’s packed with mega-selling smashes in, tellingly, a variety of genres: ‘Hit ‘Em Up Style (Oops!)’ by Blu Cantrell, ‘Don’t Let Me Get Me’ and ‘Just Like A Pill’ by P!nk, ‘Trick Me’ by Kelis, ‘The Boy Is Mine’ by Brandy & Monica and ‘Push The Button’ by Sugababes.

But Austin wasn’t the only youngster flexing his muscles. Beneath Executive Producer level we find Jermaine Dupri, just 22 when album came out. Something of a nepo baby (his father was a Columbia executive), Dupri made his name with the Jackson Five-sampling ‘Jump’ by fellow Atlantans Kris Kross in 1991, when he – like the backwards-clothes-wearing duo who sang it – was still a teenager. In the meantime, he discovered girl group Xscape (of whom more later), and produced the G-funk banger ‘Funkdafied’ by Da Brat. After working with TLC, Dupri went on to have a Platinum-selling Billboard top three album under his own name in 1998, and produced hits including ‘Always Be My Baby’ and ‘We Belong Together’ for Mariah Carey and ‘You Make Me Wanna’ by Usher (and pretty much any other Usher hit you care to mention), racking up a staggering total of 11 Billboard number ones.

Dallas Austin and Jermaine Dupri, then, would seem the likeliest candidates for the backroom geniuses behind CrazySexyCool. But the cold hard fact is that they only produced two tracks each out of eleven. The credits of CrazySexyCool are also shared between minor production and songwriting personnel such as Manuel Seal, Carl Thompson, Jon-John Robinson, Arnold Hennings and Debra Killings. The guest stars, too, were mostly low-profile ones. There’s Phife Dawg from A Tribe Called Quest, the nearest thing to an established name. There’s CeeLo Green, still a member of Goodie Mob and not yet a breakout star, providing BVs on a couple of tracks. There’s Busta Rhymes, who had made something of a name for himself with Leaders Of The New School but was yet to release his solo debut. And there’s André 3000, then just known as Dre, from TLC’s Atlanta buddies Outkast, who had just released their debut Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik.

And there’s also, one must acknowledge with a heavy heart, Sean Combs. But the future Puff Daddy/P. Diddy, currently the subject of over 100 lawsuits involving sexual assault and, as we speak, awaiting trial in a detention facility, didn’t have that much to do with the album (even though one member of TLC once said “he just has this way of making things happen”). That’s the thing: no one had that much to do with it. It’s all spread too thinly for any individual, or even any team, to emerge as the auteur from the ‘technical competence’ angle.

That just leaves the third element of Auteur Theory: ‘distinguishable personality’. And, oh boy, TLC had personality to burn. (Pun very much intended.) I know. I met them.

The first time I set eyes on Tionne ‘T-Boz’ Watkins, Lisa ‘Left Eye’ Lopes and Rozonda ‘Chilli’ Thomas, they were gallivanting around the Grosvenor House Hotel lobby in London, wearing matching pale grey sweatpants and tops, and no make-up. Devoid of their stage gear and camera-ready warpaint, they looked like kids. (They would, in fact, have been 23 and 24 at the time.) But they’d already been through more drama than most bands twice their age.

The group began in Atlanta, Georgia (yet to acquire the nickname Hotlanta) when producer Ian Burke and singer Crystal Jones – the original ‘C’ in TLC – put together a New Jill Swing trio around Jones, drafting in Lopes, an aspiring singer, dancer and pianist who had moved to Atlanta from Philadelphia, and Watkins, a former church choir soloist from Des Moines, Iowa. They were snapped up by Pebbitone, the management company of Perri Reid – wife of L.A. Reid and a singer herself whose hits under the name Pebbles included ‘Girlfriend’ – but Jones left when she wasn’t allowed to let an outside lawyer set eyes on Pebbitone’s contract before signing, and Rozonda Thomas, the only true Atlantan in the classic line-up, was drafted in. A former professional breakdancer, Thomas’ father was African American and Native American while her mother was of Bangladeshi and Arab descent, and had been racially abused at school with epithets like ‘Jap-girl’ and ‘wetback’. It’s a relief, then, that Pebbitone gave her the innocuous nickname ‘Chilli’ to maintain the TLC initialism.

In their early years, TLC came over as a scrappy, street-tough, garishly-clad post-Salt-N-Pepa hip hop-soul outfit, their brattish B-girl irreverence a contrast to the slickness and classiness to which most female R&B acts were expected to adhere. They also had a thing about condoms, whether advocating them or accessorising with them. In the opening seconds of ‘Ain’t 2 Proud 2 Beg’, the lead single from their 1991 debut album Ooooooohhh… On The TLC Tip, Left Eye literally has a rubber johnny over her right eye, and it’s not long before she’s craving any cock she can get: “2 inches or a yard rock hard or if it’s saggin’…”

TLC’s unabashedly sex-positive stance, like that of Salt-N-Pepa circa ‘Let’s Talk About Sex’ was a subtle shift from the messaging of 1980s Black American pop during the first years of the AIDS epidemic, when Janet Jackson told us to wait a while and Jermaine Stewart told us us we didn’t have to take our clothes off to have a good time. For TLC and Salt-N-Pepa, the message was: don’t wait, get your clothes off, but – in the words of Jeremy Kyle – put something on the end of it. (Left Eye once appeared on an ABC sex education show demonstrating how to make an improvised dental dam using wrapping paper.)

The UK was mostly unmoved by TLC Mk.1, but in the US they soon became medium-sized stars, with three top 10 hits and a 4x platinum album. Their celebrity status went into overdrive when Lopes began a tempestuous relationship with Andre Rison, a wide receiver for the Atlanta Falcons. In June 1994, the pair made headlines when Lopes burned down the mansion in which they lived. On a previous occasion, having found Rison in bed with another woman, she had filled the marble hot tub with teddy bears he’d given her, and cremated them. Rison replaced the tub with a cheaper fibreglass model, with catastrophic consequences. After another argument, Lopes filled the jacuzzi with Rison’s trainers and trophies, and started another fire. This time, the plastic melted, the wooden frame caught, and the whole house went up in flames. That same night, three of Rison’s cars were smashed up beyond repair. In the aftermath, Lopes was fined and ordered into alcoholic rehab.

This stuff, of course, was priceless ammo when it came to selling the idea of a TLC story to my bosses at Melody Maker. At the time, battle lines similar to the famous Hip Hop Wars at NME in the 80s had arisen at the Maker. On the one hand, a coterie of what would now be called Poptimists. On the other, unreconstructed dyed-in-the-wool Rockists. As a member of the former, I’d already managed to upset the latter by getting 2 Unlimited, and then Warren G & Snoop Doggy Dogg, on the magazine’s front cover for a Eurodisco and G-funk issue respectively. And now, here I was again, arguing that a predominantly indie rock magazine really needed to feature this R&B girl group who, to the untrained eye, might as well have been SWV or Jade or Nuttin’ NYCe, or whatever. Arson won me the argument, and off to the Grosvenor I went.

There was one catch. The press officer, who was sitting in on the interview (the first time I ever experienced such a thing), had told me I could ask them about anything other than the fire. But how was I going to go back to Maker towers and face editor Allan Jones and features editor Paul Lester without a quote on the single most scandalously newsworthy angle to the whole TLC tale?

I decided to formulate my question in a crafty way. Something along the lines of saying that I realise that there’s one subject they’d rather not talk ab…

Before I’d even finished the question, Left Eye interrupted me. “Hell, we’ll talk about it!” Inwardly, I was punching the air. (And I could feel red lasers from the press officer’s eyes burning into the side of my head.)

I asked Lopes whether she regretted what she did, and whether setting fire to her boyfriend’s stuff was an overreaction. “Hell, NO!”, she replied, fixing me with her big black-brown eyes (all iris and pupils, no white). “I think the media over-reacted a little! It’s been everywhere, I couldn’t turn on the TV or open a magazine without seeing my own face staring back at me. And next to it, there’s this story which they didn’t even get from me, because I haven’t spoken to anyone, so they’ve got it second hand — no, tenth, eleventh hand — from reading other articles, from the Atlanta Chronicle, whatever. There are only two people who really know what happened that night. All anyone else knows is, there was a fire, and some cars were smashed up. Also, every article is about how terrible it is for Andre, because he’s this male sports hero, but no one considers my feelings, or how it is for me! That was my home, too. They write all these lies, and there’s nothing I can do about it. And whatever I say wouldn’t stop them. They just want people to see me as this crazy, jealous bitch who burnt her husband’s house down.”

T-Boz chipped in at this point. “Like, she’d really wanted to do that?! There were people asleep upstairs! She’s not that crazy!” At which point Left Eye delivered the quote that I still laugh about whenever I remember that encounter. “But I will tell you this much. It wasn’t me who smashed those cars up. And I didn’t burn the house down. I set fire to something. I didn’t mean to set fire to the whole damn HOUSE!”

My Maker article also went into the darker side of the saga, including allegations of violent behaviour from Rison towards Lopes, and her childhood with a violent alcoholic father, to counterbalance the simplistic ‘what a nutter’ narrative. (But TLC themselves were not averse to having fun with the mansion fire story, famously posing on the front cover of Vibe in firefighter uniforms.)

Two years before Spice Girls existed, TLC were a girl group whose individual members were each assigned cartoonish roles. Loose cannon Left Eye, it barely needs stating, represented the ‘Crazy’ in CrazySexyCool. T-Boz, with what the album’s Phife Dawg/Andre 3000 intro calls “the ill haircut” (a steeply graduated blonde bob with a one inch tramline down the middle), was the ‘Cool’, which left Chilli with ‘Sexy’ by default. “I think of CrazySexyCool as an ‘I’m Every Woman’ for the 90s,” T-Boz told me. “Because all three characteristics exist in every woman. And every man! It just depends how you feel when you wake up in the morning…”

In person, I actually found T-Boz quiet and guarded (on that day, in any case), Chilli charmingly prim and proper (she’d carefully say ‘Oh my gosh’ instead of ‘Oh my god’, and “BS” instead of ‘bullshit’), and Left Eye every bit as hyper-sassy and sparky as you’d have expected. Like I say, ‘distinguishable personality’ to burn.

But what drew me to TLC, and inspired me to write about them, wasn’t the fire, or even the personalities. It was the record, a hip hop Soul opus which was – as I loudly proclaimed to anyone who would listen – a masterpiece. But, if that were the case, whither the third element of Auteur Theory, ‘Interior Meaning’? A record with so many contributors shouldn’t, by rights, have any kind of cohesive mood or theme. But CrazySexyCool has two main threads. Firstly, it is steeped, as much as any record by white guys with guitars from the same era, in a certain Gen-X malaise and Pre-Millennium dread. Secondly, it expresses a confident sex-positive feminism throughout.

The opening track, Dallas Austin’s incredible infidelity narrative ‘Creep’, is a stealthy Swingbeat classic (and the greatest song called ‘Creep’ of the 90s, don’t @ me). After a bit of “Yes, it’s me again…” scene-setting from T-Boz, its first words are “The 22nd of Loneliness…” Inventing a month called Loneliness, and addressing the listener from the 22nd day of it: that’s a baller move, lyrically. That’s a Prince move. Straight from the start, CrazySexyCool reminded me of Prince (at a time when the Minneapolitan’s music had fallen far from fashion and favour). Stick it on now, and listen to the way the syllables of the words “I keep giving loving till the day he pushes me away”, equally-weighted, pile up and pile up until they’ve strayed halfway into where the next line ought to be. It’s pure Prince. (Specifically, it’s like something out of ‘Love… Thy Will Be Done’, the track Prince wrote and produced for Martika.)

The album’s biggest hit, the mid-paced, Organized Noize-produced ‘Waterfalls’ felt epochal, surveying the damage done to the 90s generation by gang violence, addiction and unprotected sex, with a memorable rap by Left Eye: “I seen a rainbow yesterday/But too many storms have come and gone/Leaving a trace of not one God-given ray/Is it because my life is ten shades of grey…” The most obvious inspiration for the phrase “don’t go chasing waterfalls” was a Paul McCartney single from 1980, but ‘Waterfalls’ was, again, very Princely in its aural palette. Those weird clipped wah-wah guitar notes, and the synthetic horn sounds, were pure Paisley Park. Furthermore, the line “three letters took him to his final resting place” in the verse about HIV recalled the man in France who succumbed to “a big disease with a little name” in ‘Sign ‘O’ The Times’.

As a matter of fact, at the time I met them, word had reached me that TLC were actually going to work with Prince (which the trio themselves confirmed, albeit a little unsettled that I knew about it), though nothing ever came of the collab.

To make the album’s debt to Prince even clearer, there’s even a (Combs-produced) cover of ‘If I Was Your Girlfriend’. Prince’s 1986 original already pretzels your brain into an Escher staircase of twisting perspectives, as he pursues a level of intimacy that’s unsettling, almost sinister, taking the gender-swapping reverie of Kate Bush’s ‘Running Up That Hill’ to an extreme. Its suggestion of lesbianism, heightened by the lost-in-translation nuances of the word ‘girlfriend’ in British English (your GF) American English (your friend who is a girl), becomes even more literal when sung by three women without changing the pronouns, a bold move in 1994. “We only changed one ‘he’ to a ‘she’ or something,” T-Boz told me. “But in a way, we’re already girls, we’re making it more simple. If you look at it like that…”

Another bold move was the unambiguous reference to cunnilingus in straight-down-the-line sex ballad ‘Red Light Special”’ in which T-Boz promises “I’ll let you touch it, if you’d like to go down/I’ll let you go further if you take the Southern route…” Given that her audience was largely a hip hop culture in which a lot of men were still a bit Uncle Junior about such things – too macho to muffdive – this was a subtly provocative assertion of female power in the bedroom.

Other highlights include Dallas Austin’s O’Jays-interpolating ‘Case Of The Fake People’ (a late addition, not even listed on the LP sleeve) and Jermaine Dupri’s ‘Switch’ (which samples Jean Knight’s ‘Mr. Big Stuff’ to great effect), but even the more generic numbers, like ‘Kick Your Game’, ‘Let’s Do It Again’, ‘Diggin’ On You’ and ‘Take Our Time’ have a creamy gorgeousness to them which enhances the seamless flow.

Did I say ‘seamless’? Well, not quite. CrazySexyCool is punctuated by half a dozen comedy skits, as per the trend in 1990s hip hop (the “torture, motherfucker” dialogue on Wu-Tang Clan’s 36 Chambers being the ultimate). At the time, I compared these flaws to the deliberate imperfection woven into every Islamic rug, because only Allah is allowed to be perfect. The one which kills the vibe the most is ‘Sexy – Interlude’, midway through Side 2, on which Chilli prank-calls some hapless male employee (actually Combs) at a take-away restaurant, Jerky Boys-style, and snares him with some heavy-breathing sexy talk, before the final brutal switcheroo: “I want you to help me… I want you to… I want you to… I want you to pass me some tissue, SO I CAN WIPE MY ASS!!!”

The album ends, though, with perhaps its finest moment: the existential grandeur of ‘Sumthin’ Wicked This Way Comes’, Another Organized Noize jam built on a slow and steady progression of deliciously old school rock guitar chords, with a hyperactive Andre 3000 intro taking a sideswipe at Jacko and making the on-brand brag “I go through obstacles like a whole box of condoms”, an angst-ridded T-Boz chorus that confesses “Sometimes I feel like there’s nothing to live for” and a truly thrilling Left Eye rap towards the end.

Speaking of which, perhaps the most extraordinary thing of all about CrazySexyCool is that the record is dominated by someone who was barely there. Lopes was only able to visit the studio for a couple of days, on release from state-enforced rehab, but delivered rap bars which crackle with static. (According to an NME interview with T-Boz on the album’s 25th anniversary, Lopes wrote them all while sat sideways in a toilet cubicle, smoking weed.) For all the superbly sultry vocals of T-Boz and Chilli, it’s Left Eye’s album. She’s like the actor who makes a one-minute cameo but somehow steals the film.

It took five years for TLC to follow CrazySexyCool. During that time, T-Boz was laid low with sickle cell anaemia, Chilli had a baby with Dallas Austin, and they all fell out with each other, to the point that Left Eye, who was especially disenchanted with the strictures of TLC and their management, challenged the other two to a bizarre solo album contest to see whose would sell the most. (Neither singer accepted.)

1999’s FanMail saw TLC embrace futurism, with cyberpunk styling, and space-set Hype Williams videos. They were early adopters of the internet, marshalling their fandom online, although membership of the TLC fan club actually granted you little that was more modern than branded notepaper, pencils and rubbers (the erasing kind, not the prophylactic kind).

FanMail‘s lead single, ‘No Scrubs’, became TLC’s signature tune (even more so than ‘Waterfalls’). Any DJ will know that, to this day, there is almost no context in which dropping “No Scrubs” into your set won’t cause the crowd to absolutely lose their shit. Its lyrics, though, bear a closer look. In the song, Chilli addresses a ‘deadbeat’ who “sits on his broke ass” and lives at home with his momma, but who has the temerity to be “hanging out the passenger side of your best friend’s ride, trying to holler at me”. She lets him know in no uncertain terms that he has no chance: “Wanna get with me with no money? Oh no, I don’t want no scrubs…”

A brief history, then, of skint-shaming in black American pop. In 1986, New Jersey R&B singer Gwen Guthrie scored a worldwide hit with ‘Ain’t Nothin’ Goin’ On But The Rent’, with the repeated refrain “Got to have a J-O-B if you wanna be with me.” It dropped bang in the middle of the 80s, the decade in which Thatcherism and Reaganomics had consigned millions of young men to the dole queue, and added insult to injury every time it blared out over the airwaves (banger though it was). Skint-shaming didn’t originate there, of course – you could go right back to Carla Thomas playfully mocking the unsophisticated and penniless Otis Redding in their duet ‘Tramp’ (“You haven’t even got a fat bankroll in your pocket/You probably haven’t even got twenty-five cents…”) – but Gwen Guthrie’s hit is the pertinent place to start, and feels like the direct antecedent of ‘No Scrubs’.

By picking up Guthrie’s theme, TLC inspired others to do the same. Destiny’s Child, TLC’s direct successors as a world-conquering R&B girl group, literally used the word ‘scrub’ in ‘Bills, Bills, Bills’, released a few months later, during whose chorus they coldly demand of a potential suitor whether he’s able to pay their telephone bills, automo-bills etc, the irresistible response from the listener being “Pay them your fucking self!” (Admittedly, in the verses, it’s clear that the perpetrator has been genuinely taking the piss, going on shopping sprees and maxing out Beyonce’s credit card.) The lyric to ‘Bills, Bills, Bills’ was written by Kandi Burruss, Xscape member turned songwriter (and, latterly, Real Housewives star), about her former boyfriend, Jagged Edge member Brandon Casey (who by this point, ironically, was dating Destiny’s Child member LaTavia Roberson). Was the skint-shaming theme and the use of the word ‘scrubs’ just a coincidence? Absolutely not. Because guess who co-wrote ‘No Scrubs’ itself? Kandi Burruss.

These songs spurred a backlash of sorts. In 1995, on their debut album Operation Stackola, Oakland rap duo Luniz belatedly bit back at Guthrie, directly interpolating ‘Ain’t Nothin’ Goin’ On But The Rent’ on the self-explanatory ‘Broke Hos Is A No-No’. (Of course, Luniz were only skint-shaming from the other side, rather than critiquing the shaming itself.)

And ‘No Scrubs’ prompted an actual answer record in the form of ‘No Pigeons’ by Funkmaster Flex-endorsed crew Sporty Thievz, which was entirely built on the original’s instrumental track, and released in artwork which parodied the TLC sleeve, taunting the so-called ‘pigeon’ (it was originally going to be ‘vulture’) with couplets like “Your pussy ain’t worth the Ramada/Anyway, your friend looks hotter”, and listing her physical defects (dirty braids, flat ass, manky feet, moustache). It even took aim at Left Eye with the line “My left ear be worth double her get-up”. And, in case we missed the point, the B-side was called ‘Cheapskate (You Ain’t Gettin’ Nada)’.

This was, however, something of a phoney war: ‘No Pigeons’ was released on Ruffhouse/Columbia, ultimately part of Sony. ‘No Scrubs’ was on LaFace/Arista, ultimately part of Sony. And Kandi Burruss and co-writer Kevin ‘Shek’speare’ Briggs got the royalties, whichever one was played on the radio. Ker-chinggg!

Before this all gets too Incel/Fathers For Justice, make no mistake. The guy in the TLC song is a catcalling cunt, and catcalling cunts deserve what they get. It’s just that ‘No Scrubs’ left the listener with the impression that if the ride was his own, and his ass wasn’t broke, Chilli/Kandi wouldn’t have minded the catcalling so much.

However, the message of TLC’s next single ‘Unpretty’, dealing with societally-inflicted self-esteem issues and female body image, was unarguable. And it was self-penned, written by T-Boz from her hospital bed while watching an episode of Ricki Lake in which women were disparaged as “fat pigs”. The lyric chimed with an entire generation of girls, and followed ‘No Scrubs’ to the top of the Billboard charts for three weeks.

All of this was still in the future when CrazySexyCool conquered the world. Even further into the future was Left Eye’s re-emergence as a solo star, notably with her UK No.1 collaboration with Mel C, ‘Never Be The Same Again’ in 2000, and the awesome EW&F-sampling chant-along single ‘The Block Party’ (which unaccountably flopped in the US) in 2001. Tragically, Lopes died the following year aged 30 in a car accident, while on a spiritual retreat in Honduras which was being filmed for VH1. Of all the people I’ve interviewed who are no longer with us, Left Eye is one whose untimely death still seems utterly senseless and hard to process.

TLC’s fourth album 3D was released in October 2002, mostly completed after Left Eye’s death, patching together unfinished vocals that were intended for her solo career, and they called it a day.

In 2007 there was a ropey VH1 documentary, The Last Days Of Left Eye, which captured the moments inside the car leading up to her death – I watched that, but wished I hadn’t. In 2013 there was a poorly-received made-for-TV biopic, CrazySexyCool: The TLC Story – I didn’t watch that. In 2017 there was a fifth, self-titled album by the surviving duo – I didn’t hear it. And from 2017 on, there have been gigs and festival shows by the two-piece TLC – I didn’t go. (I’m sure they were great, and the Glastonbury set looked fun. I just had other stuff on.)

But it’s CrazySexyCool itself – the vinyl copy I was unembarrassed to get autographed by all three members in the Grosvenor that day – that I keep going back to. Despite being the best-selling album of all time by an American girl group, racking up 60 million sales, it felt underrated at the time. Due to hard lobbying from the office TLC clique, it crept in at number 40 in Melody Maker‘s Albums Of 1995 (reflecting its belated UK release date), and didn’t make NME‘s list at all. Its reputation has grown in recent years, however, coming it at 43 on Rolling Stone‘s Albums Of The 90s in 2019 and 42 on Pitchfork‘s equivalent list three years later. In a just universe it would be Top 10.

But why does it keep drawing me back in? Why aren’t I listening to, say, the equally banger-packed Funky Divas by En Vogue on such a regular basis? Maybe it’s because the mysteries of CrazySexyCool are so persistently hard to unravel. With so many fingerprints all over it, there’s no single suspect for the elusive Auteur which critical convention requires in order to explain a great record. Was it just a case of the stars aligning, and a dozen different people happening to hit their absolute A-game at the same time? Perhaps. You end up trapped within a loop of circular logic: it’s magnificent because it’s magnificent.

All I know is that the next time I drop the needle into the groove and hear Phife Dawg and Andre 3000 debating which member they fancy the most, knowing that the horn stabs of ‘Creep’ are about to kick in, I won’t care how it all happened. It simply is what it is.

Crazy. Sexy. Cool.