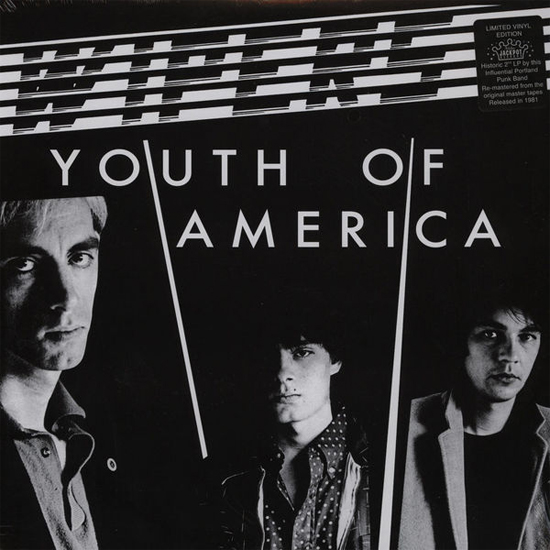

On Portland Punk Live At The Earth 10-29-79, a live-on-the-night document of local bands released warts’n’all by the Wipers’ Greg Sage on his own label, Trap, Sage can be heard introducing his band’s ‘Same Old Thing’. Overwrought with stage adrenaline and demonstrating the compassion and obsessive conviction that made him a hero to the bullshit-intolerant, the frontman blurts out: “This is about the far beyond and the non-existent and all that and in between, because I don’t really know about it but I’m gonna try to explain it…" In Sage’s outburst is contained everything that was the Portlandians’ Youth of America. 30 years old but young forever, there may be more essential punk albums out there but never again did the genre sound so searching. Eternally devoted to pushing independent music – by himself and others – from his base at Zeno Records, Sage has been trying to ‘explain’ ever since.

Naturally for an album aiming somewhere between the far beyond and the non-existent, Youth of America is a hard one to pin down. For starters, it’s a six track set of lowly garage rock which traverses the cosmos irrespective. Secondly, it’s a gothic downer but leavened by motion and momentum thanks to its Krautrock influences. And lastly it’s a grittily real punk record defined by an unerring air of unreality – as unromantic as it is fantastical. Not only that, for a largely bleak album it nevertheless owed as much to the Ramones’ cartoon colours as doubt-choked post-punk and its many shades of grey. And because Sage liked to be awkward, it’s a West Coast thrasher housing two tracks exceeding six and ten minutes in length respectively, two years before Black Flag grew their hair out and wrote the jam-tastic Side B of My War. Consequently, while tightly coiled it’s also splurging and sprawling. Add to this the fact that the trio produced the album themselves yet managed to make it improbably refined, then flatly refused to categorize it as a punk record despite many claims it was the genre’s highpoint of the decade. Then there’s Sage himself, who complicates matters further.

On Youth of America he is both defeated by impotent rage and consumed by a lust for unknown pleasures, self-discovery, and change. He’s also at once the consummate individualist and a fraternal altruist, taking very seriously his self-appointed role as a leader of teen armies. Most notable is Sage’s futureless vision, at odds with his impulse to predict revolution. (Remind you of anyone? Here’s a clue: he was one of the guys in Nirvana and the Wipers’ biggest fan.) In summary, had Magazine’s ‘Shot By Both Sides’ been fronted by Tom Verlaine, powered by Klaus Dinger and featured Joy Division-era Bernard Sumner on guitar, you’d have the Wipers’ cult classic. A neat synopsis which nevertheless offers no explanation as to why, at points, Y.O.A. sounds something like the meaning of life. Or at least Greg Sage’s quest for it.

If anywhere, the answer lies in the transcendent title track – Sage’s State of the Union address and roughly speaking the 80s’ most powerful ten and a half minutes. Rubbing shoulders with the likes of ‘Teen Age Riot’ and ‘Marquee Moon’ in the pantheon of punk’s finest long players, ‘Youth of America’ is a masterpiece of sustained intensity, and as chillingly portentous as West Coast punk got. Sage has spoken in the past of having always felt somehow clairvoyant, and on the evidence of ‘Youth of America’ he may well have fluked the right answer. AMG described it as a “nightmare locomotive”. With suicidal abandon it surges on steam-turbine workings towards some unspecified disaster. Or, to put a name to the devil…Reaganite America, which for a working class punk like Sage amounted to an insidious cultural revolution. One which in a very real sense ‘Youth of America’ anticipates. Working through an onslaught of ice-cold licks hatched over a relentless motorik glide, and not one but two utterly garrotting guitar solos, on every level Sage entreats his peers to act now or face the consequences.

At the midway point the track descends into psychedelic delirium. Sage whispers “Now there’s no place left to go…Got to get off this rot…Can’t wait much longer, hurry…” Both an S.O.S. to the audience and a paranoiac interior monologue, by the time the track reverts to its scything lead line and so reclaims its hungry sense of purpose, the listener more than shares in his youthful impatience and is ready to act: rock & roll fulfilling its first and most basic function.

As naïve as it seems by contemporary standards, Sage’s level of passion on ‘Youth of America’ is ageless. “It is time we rectify this now”, he screams. “Now, now, now, now." According to him “men in disguises” were coming for us, he claimed that the kids were up against the wall, and that he was the only one that gave a hoot. All of which might seem generic and cliched, if not for the fact that he delivers the lines as if wholly convinced he was the first and possibly last man to ever give it to ’em straight.

As it turned out, he almost was. Soon after, with their post modern knowingness Sonic Youth, The Jesus and Mary Chain, Pavement, Beck, and Weezer together killed Sage’s brand of uncoded righteousness. Indeed, if for nothing else Billy Corgan can be lauded for calling on his peers to “crucify the insincere”. Echoing through the ages, from an era which seems all but another dimension in pop cultural terms, there’s a dignity to Sage’s unselfconscious zealotry.

If Stephen Malkmus once said of his band’s music “Hey man, its not life and death”, then the Wipers are Pavement’s absolute antithesis in that for Sage it absolutely was, and everything in between. A cliché though it may be, ‘Youth of America’ is a love letter to the redemptive power of rock & roll, as fine as any in history. “Take the risk”, Sage purrs teasingly. “Let it expand your imagination…”

Which is not to say the trio blow their load all on one song. An auspicious opener, ‘No Fair’ begins with heralding, dramatic fretwork, as if urging the listeners to their seats so The Wipers can tell them a story about America. This continues for a while, until a heavily reverbed “It’s not fair!” rings out, igniting the metronomic rhythm which more or less persists for the entire duration of the album. In a superb example of album editing, ‘No Fair’ ends in a fade out, leaving the listener hanging precariously. Thusly, we are poised at the jumping off point that ‘Youth of America’ plunges from, serving to heighten the title track’s sense of occasion.

Of course, as far back as Portland’s The Kingsmen and Tacoma’s The Sonics, for reasons unknown the Pacific Northwest had been a bastion of dark, bold delinquency; conceivably because it’s such a gloomy setting. (Reportedly synaesthetic, Sage’s music was said to be the exact colour of Portland’s frequently moody skyline.) Art Chantry, who for years designed thousands of the posters that would help define the region’s unique aesthetic, said of the Wipers, “If there is a transitional band between The Sonics and grunge, it was them. They had that intensity down pat." Never ones to disappoint their grizzled Oregonian brethren, on ‘Can This Be’ The Wipers take a break from saving the world to fire off a Northwestern standard. A throwback to their debut’s concise punk and its themes of disorientation, ‘Can This Be’ can only be the work of a PNW band: more tuneful than most LA punks and sonorous next to the genre’s often tinny recordings. This was thanks in part to Sage, who for a punk musician had an abnormal commitment to the bass guitar (he started out on the instrument). Notwithstanding, it’s also piercingly sharp, as was everything the Wipers put out. Following on from ‘Can This Be’, ‘Taking Too Long’ on the other hand is a relatively sophisticated piece – delicate frills of guitar draped over a more relaxed tempo and a trilling piano part. It’s also the album’s least memorable track, solely for the fact that it’s the most unassuming.

The penultimate outing on Youth of America, ‘Pushing the Extreme’ succeeds in being camp, abrasive and ghoulish all at the same time; embodied in Sage’s perfectly positioned caterwaul of “So you think your soul is free?” This is essentially the punk equivalent of an evil laugh emanating from a lone turret at night. On the breakdown, delay is used on the cymbals so that they ricochet around the mix, both heightening the air of draughty gothica and needling those proto-Yuppies like a bad conscience, on the eve of their deal with the devil. “Through your mirror there is such vanity,” Sage narrates. “You know, child… we used to be in it for the same thing. But now it’s one against the other…”

Almost seven minutes long, the apocalyptic closer ‘When It’s Over’ is very nearly ‘Youth of America”s equal, albeit lacking in the latter’s iconic dimensions. Beginning with an extended instrumental, drummer Brad Naish and bassist Brad Davidson hold fast against the storm Sage summons with his guitar. Just when the histrionics reach an operatic level, an ascending four-note piano-line takes over, righting the song but also adding another section of track to the railroad through hell. All the while Sage murmurs from the abyss, things like: “In the land of dreams I find myself sober,” and “Do you think we’ll ever be saved?”.

Matters continue on course until suddenly… detonation. “ALL BE OVER!” Sage screams as the pregnant calm is blown to smithereens by sheer, eye-watering dissonance. The sound a Gibson makes as it’s dissected by a diamond wire-cutter. After that, all there’s left to do is repeat the first suite and let Sage have the last word, which he does so in the form of a question. As a great and worthy album expires, he asks “Will you be laughing… when it’s over?” The Wipers – they’d have been huge if only they hadn’t asked too many questions.