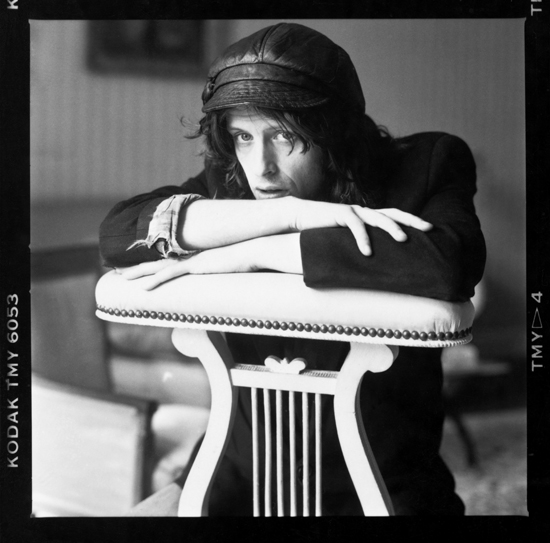

You only had to take one look at Mike Scott in the early 1980s to know that he was born to write. His carefully cultivated appearance – long dark overcoat with collar turned up to the wind, shoulder length hair only a shampoo away from Bob Geldof’s unkempt mop and tucked away beneath a Greek fisherman’s cap – gave him the look of a poet, conveying an earnest, literary image no doubt enhanced by his study of English literature in his native Edinburgh. Like Morrissey, who formed The Smiths around much the same time as The Waterboys were born, Scott was a bookish romantic and also a product of punk culture: while Morrissey was running the New York Dolls fan club, Scott was publishing a fanzine, Jungleland. But unlike Morrissey, Scott wasn’t immersed in the kitchen sink culture of 1950s England encapsulated by Alan Sillitoe, and neither did he write of gritty streets and the day-to-day minutiae of dreary disappointment. Instead he buried himself in the work of William Butler Yeats, Robbie Burns and William Blake, dreaming of "unicorns and cannonballs, palaces and piers / Trumpets, towers and tenements, wide oceans full of tears". Scott sought to give voice to a sense of the epic rather than the prosaic, almost guitar music’s polar opposite of The Smiths, and he wasn’t alone: U2 had made tentative steps towards grand themes on their early releases just as The Waterboys had on their first two impressive but nonetheless mildly technologically hamstrung albums. By 1985, however, the year that their third album, This Is The Sea, emerged, Scott had perfected a concept that The Unforgettable Fire, a year earlier, could only aspire to, a sound that rapidly became known as ‘The Big Music’.

It took its name from a Waterboys song, the first single to be released from their second album, A Pagan Place. Though metaphorical in intent, its lyrics applied perfectly to the scale and grandeur with which Scott was beginning to carve his style: "I have heard the big music," he sang, "and I’ll never be the same… I have climbed the big tree, touched the big sky / I just stuck my hand up in the air / and everything came into colour / Like jazz manna from sweet, sweet chariots". The album, however, was less successful at creating this sense of sweet euphoria: though its aim was ambitious – something to which opener ‘A Church Not Made With Hands’ and the mournful ‘The Thrill Is Gone’ testify, not to mention the eight minute waltz of ‘Red Army Blues’ – its reach sometimes fell somewhere short of Scott’s target, partially due to the claustrophobic sound, a result of the fact that some of its tracks were little more than glorified demos. But that was, as Scott would have it, the river, and now he was looking to further, wider horizons: to the sea. With its follow up, Scott wasn’t going to make the same mistake again.

From its opening brass fanfare to its closing multi-tracked 12 string guitars, This Is The Sea defined ‘The Big Music’. If the song itself had been, as Scott says, "about perceiving spirit in the world, about being touched by a sense of the sacred", then the new album was an epic collection that searched for spiritual meaning and, astonishingly, communicated it. Packed with handsomely poetic, almost archaic language and blessed with a rich diversity of instrumentation, it was also the beneficiary of improved studio technology, something that Scott is modest enough to admit.

"I think the recording technology of the day fostered the ‘big’ sound," he says now. "This was the era of big snare sounds, and newly developed reverbs and echoes that added depth and space to records. And after the primal return to Punk of several years earlier, people – record-makers and listeners alike – were ready to have a more sophisticated sonic experience again."

But there was more to it than that. Unlike the Eno & Lanois soundscapes that U2 had adopted the year before, or the ostentatious luxury of Trevor Horn’s contemporary production work, This Is The Sea‘s sound was honest and organic, true to – but not tied down by – his punk roots. It seemed authentic, the product of creative inspiration captured at the moment it struck, Scott’s voice the key, characterised by its irrepressible passion, the musicians carried along with him, united behind his cause. Scott credits this solidarity light-heartedly to "hunger", but the sense that they were all there in the studio, buzzing on the adrenalin provoked by the cosmic themes, "high on the wine of life", lent the album a profound sincerity. Over 25 years later, its potency still sounds almost unaffected by changes in stylistic tastes, with even prominent use of a saxophone forgivable thanks largely to Anthony Thistlethwaite’s ability to lift a melody like Clarence Clemons.

At its heart lay Scott’s preference for multi-tracking, a technique he confesses was discovered accidentally. "When I made the first Waterboys album – which began as demos – I would try playing two 12 string rhythm guitars," he recalls. "I found that when I played the second one immediately after the first, I could still remember every nuance of the playing on the first one, and so as I played the second I could exactly match those nuances or – and this was important – play subtly different to the first, with little rhythmic comments and echoes.

"When these two performances were then split into wide stereo – one in each speaker – it made a wonderful sound. It was like two musicians incredibly in tune with each other weaving a kind of aural tapestry. And with 24 strings it was huge. When I added a piano, played in my own self-taught idiosyncratic way with a kind of rolling duddle-uddle-uddle groove, I suddenly had a wall of sound."

It’s not a Spector-esque ‘wall of sound’, however. This Is The Sea is too in love with open spaces to allow for any sense of boundaries. Instead it brings walls tumbling down, sending light flooding across an often mythical landscape, conjuring spirits, calling out to a universal force. It’s fantastic: for its exuberance, its sentiments, its poetry and its ambition. It’s also fantastic in the truest sense of the word: "extravagantly fanciful". It comes as little surprise, therefore, to read Scott’s sleeve-notes for the newly released In A Special Place – a collection comprised of, mainly, the album’s very first demos – to discover that the record was conjured up out of the pages of a ‘Book Of Shadows’, a volume intended to allow witches to write down their spells and rituals. In a typically elaborate introduction, he evokes the appropriately mysterious tale of its discovery.

"One wild January day, when the wind charged like stampedes of wild horses down the mighty avenues, I walked down a narrow backstreet and discovered the most curious shop I’d ever seen. It was a witches’ store, its shelves filled with potions, grimoires, scraps of wood, bark and root and numberless weird things I had no words or names for. And as I squinted around this dark space my eye was attracted by a massive, enigmatic-looking black-bound book."

It’s a scene that seems to have been torn from the pages of a nineteenth century novel by Percy Bysshe Shelley, but Scott’s in fact referring to New York in the mid 1980s, and this ‘Book Of Shadows’ would soon contain, written in his self-confessed "tiny hieroglyphic writing", everything that would become, only a few months later, his musical masterpiece. Listening to the windswept, grandiose majesty of This Is The Sea, it seems an undeniably appropriate source of inspiration for its recording.

The release of In A Special Place sheds revealing light on the process in which Scott engaged to create This Is The Sea, throwing the care with which he worked into sharp relief. With his ‘Book Of Shadows’ propped open before him, the songs often only half complete, Scott tracked his way through its contents on just piano and vocals for co-producer John Brand "as a way of introducing him to the material and also of helping me to sift through it". So the triumphant opener, ‘Don’t Bang The Drum’, is performed as a tender ballad, ‘Be My Enemy”s bile is even more bitter for its lack of distractions, while ‘The Pan Within’ is full of tremulous pleading. He’d later tweak melodies and words, entire verses, sometimes themes, discarding what didn’t work, sometimes employing ideas elsewhere.

"For the song ‘This Is The Sea’, for instance, I had about twenty verses", he claims, and close examination of the lyrics employed on these demos shows the lengths to which Scott went to perfect them, ‘The Whole Of The Moon’ missing its "too high, too far, too soon" payoff and most obviously still in an early state of genesis. A slightly later recording of ‘Old England’, with Scott adding guitars and Karl Wallinger (later of World Party) on drums and bass synth, is also included, providing another intriguing glimpse at the way he built up arrangements, though Scott suggests that "even when I did the demos I was imagining all the other instrumentation on top".

Yet the performances, in all their rawness, are more than just a curio, and given that the album’s 2004 reissue offered an additional ten tracks that didn’t make the cut – some of them, like ‘Beverly Penn’, particularly strong, though inappropriate for the atmosphere Scott was seeking to capture – it’s remarkable to discover a further eight songs that were pencilled in for inclusion. It’s especially impressive since there are others that still aren’t available – Scott claims he had 30-40 songs prepared for the record – and only serves to emphasise the creative wave Scott was riding. But even though songs were, as he puts it, "coming out of my ears", it belies the difficulties that he was experiencing in attempting to mould his masterpiece. No longer could he simply "put his hand up in the air" to pluck "jazz manna" from the heavens.

"The songwriting was hard," he says today, "because, like many other artists before or since, when I had my first taste of public attention and success, I grew suddenly self-conscious about my songwriting and record-making processes. So when I made This Is The Sea I was dealing with that in addition to the usual process of creativity. This slowed me down and made the work more difficult than it had been on the first two albums, which were done very unselfconsciously. I managed to overcome these issues by a combination of excitement in what I was doing, willpower to be successful, and the good policy of ‘following instructions’, by which I mean doing what the music told me to. I still do this today.

"It’s become second nature, the way I live my musical life. If I’m working on something and have a decision to make, I listen to the track (if it’s a recording in progress) or play the song, and I keep alert for what the music is saying to me and it always, always, always tells me what to do. And I fucking do it!"

It was a policy that paid off, and the suggestion that a higher force was in some way involved suits the record well. This Is The Sea is packed with spiritual references – "This is sacred ground with the power running through" (‘Don’t Bang The Drum’), ‘Man is tied, bound, torn / Spirit is free / What spirit is, man can be" (‘Spirit’), "Your heart is like a church with wide open doors" (‘Trumpets’), "Turn your back on your soulless days" and ‘You’re trying to make sense of something that you just don’t see", (‘This Is The Sea’) – and there is a joyful sense throughout that, even when battling demons, the world offers an abundance of mysterious magic that offers more than enough to live for even if we don’t understand its source. But these allusions are inclusive: they don’t adhere to any particular religion, calling upon Greek mythology as often as Christianity, at one point invoking the legend of Brigadoon (though in truth this was a mere forty years old). Even the use of William Strutt’s painting ‘Peace, and a little child shall lead them’ on the inner sleeve of the album only came about because Scott took a liking to it – "The image says to me: gentleness has power in it" – after seeing it on his friend Mark Nevin’s (of Fairground Attraction) mantelpiece.

"I don’t believe in a ‘higher power’," Scott elaborates, "because I believe we are all God and the power of the sacred is within each of us (and accessible to us.) I believe that everything is connected, that we create the conditions of our own lives and consciousnesses by the attitudes we adopt, the decisions we make and the actions we do. I believe in the law of karma – that whatever we do is visited back on us in exact degree though not necessarily in the same form – and I believe love is the supreme force in the universe, and that we are at our most real when we are acting with love. I don’t belong to any religion and I personally find church Christianity, those kinds found in the British Isles and Ireland under their various names, to be grey, colourless, dead and with virtually nothing of God or spirituality left in them, whatever luminosity may have attended or informed their distant origins. If I had my way I’d close them down."

Consequently, This Is The Sea is far from a religious record – though it is one full of epiphanies – and is as much in love with the natural world as it is with the spiritual world, often making little distinction between the two, building metaphors from what Scott both sees and senses around him.

"One of my earliest memories," Scott remembers when asked whether he’s a city boy or a country boy, "is of standing in the back garden of a hotel in Norfolk, age of four probably, on holiday with my family, and noticing where the garden gave way to wild woodland. I walked up to the cusp of the woodland and felt a strong emotion and atmosphere – full of an almost tactile loving desire – that even today I can still conjure and feel again. I said to myself there and then, ‘This is my kingdom’."

But though This Is The Sea is a modern record born of wonder at what surrounds us, it employs a vocabulary that is at times antiquated – never twee, however – and calls upon writers that inspired Scott such as Yeats and Blake, Keats and C.S. Lewis, Burns and Joyce. It rejects rock’s more commonplace language without fear of alienating those unfamiliar with such a style, and in so doing lends the album a charming gravitas and a timeless quality that match its themes. Part of its appeal, however, lies in the fact that it is far from blind to the world’s problems, its optimism and love balanced by an acknowledgement of the evil prevalent around us. It is, in other words, a mature vision of the world, viewed through a far from rose-tinted lens.

It begins with a rousing salute, a call to arms courtesy of Roddy Lorimer’s trumpet, the instrumental prelude to the ferocious ‘Don’t Bang The Drum’ where Scott then welcomes us with a question – "Well here we are, in a special place: what are we going to do here?" – that he goes on to spend the next 42 minutes answering with relish. Blessed with top-notch production this time – his voice recorded with some of the same cavernous qualities that Brand had employed during the initial demos, the snare drum thumped with fury, guitars chugging but blurred, Thistlethwaite’s sax jubilant – it’s a thrilling start that only fades away to make room for ‘The Whole Of The Moon’, a song that, having charted twice, now rightfully claims a place amongst the classics. Its premise is that there are those who travel "too high, too far, too soon" in their pursuit of knowledge, but like the artists who inspired him and whom he’s here addressing, Scott himself holds nothing back in his own attempt to see more than "the crescent". The song builds continuously, adding layer upon layer of instrumentation, spectacular image after image reeled off as Scott compares himself humbly to his heroes – "I pictured a rainbow / You held it in your hands", "I spoke about wings / You just flew" – until finally it almost collapses under the weight of its own enthusiasm, the sound of a comet ‘"blazing" across the speakers over Lorimer’s celebratory brass and Scott’s invocation of "every precious dream and vision underneath the stars".

But Scott’s only just getting going, and This Is The Sea has another seven tracks of similar brilliance yet ahead. The short "poem-song" ‘Spirit’ drifts in and out within less than two minutes, half the length of the original version that Scott had wanted to include (and later squeezed onto the 2004 reissue) but still barely able to contain Scott’s passion. ‘The Pan Within’ calls upon listeners to "Close your eyes, breathe slow and we will begin / To look together for the Pan within", the entreaty accompanied by an especially impressive performance from Steve Wickham, whose violin swings wildly from elated to unsettling as Scott works himself up to the moment that "The stars are alive and nights like these were born to be sanctified by you and me". ‘Medicine Bow’ is even more breathless, music and text in perfect synchronicity: "There’s a black wind blowing, a typhoon on the rise / Pummelling rain, murderous skies" he sings as guitars churn beneath the surface and drums are hammered by Thor himself. It’s as though the song is being whipped by a storm as they race "through the driving snow" to their destination, Scott almost transmogrified by the experience: "I’m gonna change my colours, throw away all my things / Stop my squawking, grow some wings…"

In its wake, ‘Old England’ slows things right down, providing a welcome five and a half minutes of contemplation. It’s arguably Scott’s finest work, a state of the nation address built upon shuffling drums and a rolling piano line, a painstakingly crafted arrangement growing with it to match the lyrical content. It personifies an idyllic vision of Albion by pointing to the decay now rife through its bloated body – "Rumours of his health are lies" – and skewering the very worst of the country’s characteristics. Reflective of those Thatcherite years – "his clothes are a dirty shade of blue" – in the aftermath of the Falklands War – "Still he sings an empire song / Still he keeps his navy strong / And sticks his flag where it ill belongs" – the song is quite simply a masterpiece, with not a word or note out of place. It develops a picture of the land as seen through the eyes of Daily Mail readers, "where the well loved flag of England flies / Where homes are warm and mothers sigh / Where comedians laugh and babies cry" and then slowly allows Scott’s revulsion to darken it with caustic references to a place "where criminals are televised, politicians fraternise / Journalists are dignified and everyone is civilised". (He revised the verse a year later at Glastonbury to include the line, "where Kinnock fumbles and Thatcher lies".)

But the most powerful moment is where he pulls back the curtain to reveal "children star(ing) with heroin eyes, heroin eyes, heroin eyes", his voice rising as he repeats the words, the language particularly startling amidst the album’s otherwise extravagant phraseology. It’s a deliberate and hugely effective sore thumb that ensures the final verse, in which even the wind is "sighing", has lost any lustre that it might otherwise have offered. If "the swans are singing" – as they only do as they die, legend has it, hence the expression ‘swan song’ – then Old England is on its last legs.

For all its disgust though, ‘Old England’ is far from spiteful, and instead a poignant, articulate lament for a country that’s lost its way. "I wouldn’t have called myself an angry young man when This Is The Sea was made," Scott comments over a quarter of a century on, "but looking at the wreckage of Britain that Thatcher and her cronies wrought, it was easy to get angry." One might argue, however, that – given strong evidence that England is currently returning to Thatcherite values – the song has never been more relevant than it is today. Scott himself is circumspect.

"I’ve spent much of the last quarter century living elsewhere," he points out, "in Ireland, USA and Findhorn, which though it has its physical being in the UK might as well be another country. When I came back to London after 10 years in 1995 I thought how loveless the culture was. Now I see our culture – I mean our mainstream everyday culture, including politics, religion, entertainment, business, education, the whole shebang – as basically dysfunctional. But somehow it keeps rolling along. When I step back and take a bigger view – seeing this era in a historical context and then, wider, in a spiritual context, I know everything is OK, however crazy it appears, and that everything is outworking in the best way it can, given the current consciousness of our culture, and of the other national and international cultures with which it interacts. If I could wave a wand and change anything it would be this: that everyone, when they’re making decisions, makes them for the good of the whole and not for the good of the individual. That’s what I’m working on in myself."

Back in 1985, however, Scott had more to say on the subject of those he found abhorrent, and he unleashes further rage immediately afterwards on ‘Be My Enemy’. Fuelled by paranoia and fury, he describes "goons on my landing, thieves on my trail / Nazis on my telephone willing me to fail" and how, with "a gun at my back, a blade at my throat / I keep on finding hate mail in the pockets of my coat". The band are his equal, too, racing impatiently towards his final declaration that "I will put right this disgrace – I will rearrange you! / Because if you’ll be my enemy, I’ll be your enemy too". If all this anger and acrimony suggest that Scott has lost sight of the sentiments expressed elsewhere, then ‘Trumpets’ soon puts that right, acting as a welcome balm to such blood and guts. An ode to love, almost rapturous in its intensity, it sees Scott stripping things back, Thistlethwaite again given centre stage, hints of bells and possibly a celeste twinkling gently in the mix, as the words compare the sensation of love to the sound of trumpets. He unveils further metaphors – "your love feels like high summer", "your life is like an ocean / I want to dive in naked, lose myself in your depths" – and rather than stretching the song beyond credulity, they’re carried by Scott’s evident devotion to the concept and by his faith in his delivery, both of which could only fail to convince those whose cynicism prevents them from at least testing the waters of his philosophy.

The album concludes with the title track, another one of Scott’s extended metaphors that overflows with positivity amidst acceptance of the difficulties of life’s journey. It’s a perfect end to the record, one that looks back at trouble and pain and, by then looking forward, accepts them as temporary blemishes on what can otherwise be beautiful. "I would have a clear intention with each song," Scott states now, "but I recognised, then as now, that a song or line has different meanings depending on the consciousness of the listener, and that it’s good to allow sufficient ambiguity to foster that process between listener and song; to allow something I can’t even guess at to happen." So the track could be interpreted as encouragement to accept some form of God into one’s life as guidance – "You say you’ve got nothing to hold on to / Nothing to trust, nothing but chains", "I can see you wavering as you try to decide" – but there’s no suggestion at any stage that the object of its address will find companionship with anyone. Instead it leaves room for the listener to maneuver within its central conceit – that what has happened is merely preparation for what will come to pass – whilst bathing in the sound of "seven or eight acoustic guitars" that roll inexorably, dramatically, onwards towards Scott’s final, softly spoken pronouncement, ‘Behold: the sea". And, with that, The Big Music is over.

In many senses, This Is The Sea represented the completion of a trilogy of albums, and though the record enjoyed significant chart success – somewhat hampered by Scott’s refusal to appear on Top Of The Pops thanks to his aversion to lip-synching – and saw the band head out on tour with Simple Minds to reach an even greater audience, Scott soon veered away from This Is The Sea‘s template rather than pursue the temptations of the stadiums that were calling his name. He refers to the album as "the creative peak of my life thus far, and the song itself was the top of that particular mountain", but as so often happens when the truly talented achieve their goals, he realised he wasn’t satisfied. "When I got up there and looked at the landscape ahead I could see a new land beckoning, one in which, instead of me imagining the record and then making it according to my blueprint, the musicians would concoct their own parts and play spontaneously in a spirit of freedom, and a different kind of energy would be channelled. This is what led to [follow-up album] Fisherman’s Blues."

And so the poet began his transformation into raggle taggle gypsy, shifting his gaze from the horizon and the heavens and opening The Waterboys’ next album three years later by imagining himself as a fisherman, "tumbling on the sea, far away from dry land and its bitter memories". Scott was now immersed in the landscape that he had admired so fondly and articulately from afar. His love of tradition and history remained intact, naturally, as did his love of sea and water– "it’s not an obsession, please" he jokes, "just a useful store of metaphor" – but those who followed his path to Dublin and on to Galway struggled for a while to adapt to his subsequent embrace of Irish folk. It was typical of Scott’s singular vision, though, born of the same commitment that made This Is The Sea so remarkable and which, with a new album in the works, continues to drive him now. So it should have come as little surprise to those who recognised the restless nature of his muse, given the opening lines to This Is The Sea’s title track. "These things you keep," he’d sung, signalling his intent, "you’d better throw them away". So he had.

Because, inevitably, that was now the river…