“Or suppose a woman has ten silver coins and loses one. Doesn’t she light a lamp, sweep the house and search carefully until she finds it? And when she finds it, she calls her friends and neighbours together and says, ‘Rejoice with me; I have found my lost coin.’” Luke 15:8-10

Sheila Davis was born in Manhattan in 1927. She would make songwriting history, but unusually for a songwriter it would not be through any of her verses, choruses, melodies or rhymes.

Davis began her career as a professional songwriter in the 1960s, securing her first bona fide hit with Ed Ames’ verbose and baroque ‘Who Will Answer’ in 1967. This was followed with a run of credits for adult contemporary solo singers like Al Martino, Laurindo Almeida and Carolyn Hester. As that run began to wane, Davis ascended the ranks of the Songwriters Guild of America.

The Songwriters Guild of America (SGA) was founded in 1931 to advance, promote and benefit the new profession of songwriting. Initially it was as a counterweight to the powerful Music Publishers Protective Association, and the SGA pioneered contracts that became industry standard. Its ranks were a reliable career route for songwriters whose commercial time was up but still had energy and experience to spare. Davis became Vice President in the late 1970s.

At the same time, she began teaching at New School University in New York, building pioneering classes in song forms and figurative language. In 1984, she published her first book The Craft Of Lyric Writing – which was followed by Successful Songwriting and The Songwriters Idea Book. Davis’ principles are as follows: songs should be about believable people in recognisable situations, express a clear attitude or emotion, be substantial enough to warrant being set to music, strike a common chord with the audience, show the singer in a favourable light, contain a built-in dilemma in need of resolution, and make millions of people want to hear them not just once but over and over.

What elevates these thick Reagan-era volumes is the practical exercises and touching focus on formal rigour. Not for Davis the vague nothings of self-help. Davis hoped that if her readers mastered the English language, the English language just might help them back. Therefore, it’s important to know that Hurt So Bad is an idiom, but Hurt So Good is a paragram.

Here’s one exercise: find a universally expressed emotion, and then peg it to an existing hit song. The start of new love? ‘We’ve Only Just Begun’. Self-assertion in hard times? ‘I Will Survive’. The end of the affair? ‘Dry Your Eyes’.

It’s very easy to see the flaws in the Davis method. In the decade leading up to the publication of her first book, the interplanetary glam of Ziggy Stardust, the heady Afro-futurism of Parliament/Funkadelic and the Olympic-standard braggadocio of the early hip hop all in different ways evidenced that escape, fantasy and play were often far more important to successful connection with audiences than hardscrabble realism. But that would be mistaking Davis for an ideologue. “Art dictates,” she stated in The Craft of Lyric Writing, “no absolutes.”

Typing “songwriting” into the Amazon search bar one night in 2002, Michael Geoffrey Skinner stumbled on the books of Sheila Davis. “She really knows what she’s talking about,” reflected Skinner in his 2012 memoir The Story Of The Streets, “to the point that what she’s telling you in a book like Songwriting Secrets almost verges on psychology.”

The English rapper and producer had heard a Reading Festival audience shouting his lyrics from his newly released debut album for the very first time. Where others might feel vindicated, Skinner was spooked. It was a warning to take his craft seriously.

On the strength of that debut, you would not think he needed assistance. What had connected with audiences on Original Pirate Material was precisely Skinner’s ‘day in the life of a geezer’ lexicon, which had imposed – as journalist Ben Thompson perceptively observed in a 2004 review – “a hilariously stringent suburban reality check on UK garage’s materialist fantasy world.”

In Skinner’s telling, Original Pirate Material had become a success by fusing the sonics of UKG – which had, by that point, ascended from South London pubs to a national British sound thanks to intoxicating crossover chart hits across 2000 and 2001 – with a punkish rejection of that genre’s lyrical preoccupations.

But some of this story is more complicated than that makes it sound.

Whilst Skinner was contending with the Mercury Prize and the Jools Holland studio, black British artists were facing the weight of Form 696 and the Metropolitan Police’s Trident operation. Both of which sought to prevent non-white crowds from gathering and non-white performers from performing. Similarly, the same type of rockist publications that had declared “UK Garage My Arse!” suddenly didn’t seem to mind when it was Skinner. Funny that. There would also be no Bo Selecta blackface caricature designed to humiliate him for a Channel 4 audience. Even funnier.

None of this is to fault Skinner, who consistently namechecked his roots whilst booking artists like Kano, Donae’o and Tinchy Stryder for features and remixes instead of the big white house names his label preferred. (Skinner has also remained heavily involved in the production, management and release of non-white British hip hop artists throughout his career.) But what it does underline is that who did and who did not get to go overground during the early 00s was sharply political.

It also helps us understand some of Skinner’s appeal. His manager, Tim Vigon, was a British guitar music guy who correctly sussed that a broad post-Britpop audience could be part of Skinner’s winning coalition.

It had partially worked: Original Pirate Material had brought glowing press and cushty appearances on telly. But it had stalled outside the UK top 10. What Mike Skinner needed was something to catapult his work to Middle England, into the suburbs and back bedrooms of a UK mainstream operating under a still-existing but fragmenting pop monoculture of Top Of The Pops and the Radio 1 A-list.

It helped that Skinner liked and understood that world. “Whatever was popular, you would pick and choose from whatever was big,” reflected Skinner of his cultural tastes growing up, in a 2014 edition of Distraction Pieces podcast, “I always held onto the belief that: with this music, I don’t expect people to be seeking me or anyone else out. I expect to try to grab people where they already are.”

Some time between the early 1960s and the middle 2000s, there was a kind of Faustian social contract in British culture: those who successfully reflected their working and lower-middle class backgrounds just might be rewarded with exiting them. This could be good and bad for those individuals’ ability to replicate that same success. With the money from his publishing deal, Skinner bought a flat in Stockwell and it would be this flat where he recorded his second album as autumn 2003 turned to winter.

For the would-be biographer, it’s the bedroom producer who causes the greatest challenge: no studio logs, no out-takes, no overeager engineers or leaky musicians ready to spill the studio tea at a few years’ remove. Early work on the record will likely never be heard, held on a laptop that was stolen during recording from Skinner’s girlfriend’s student halls. What we do know, though, is that Skinner began the project with the decision that would define the record: it would be a tightly plotted concept album.

“The story came first,” Skinner told a Reddit AMA in 2021, “every time I changed a bit of one song then I had [to] go back and change other songs. It takes more time than you think and is a massive headache.” Skinner began reading the bestselling Hollywood story consultant Robert McKee, even attending one of his seminars. The album became a fusion of two classical stories: the self-explanatory Boy Loses Girl archetype (think Romeo And Juliet) and the Biblical parable of the lost coin, which can be interpreted as the value in recovering what you already owned.

Opener ‘It Was Supposed To Be So Easy’ tees up the basic premise. Skinner plays the character Mike, an everyman figure. As per the advice of Sheila Davis, it’s the details that make us believe in this everyman: he’s in a rush to return a DVD, he’s got to call his Mum, he’s saved up £1,000 cash in a box above his telly. Suddenly, the £1,000 inexplicably disappears. Across the album, a new romance with Simone from JD Sports provides promise and temporary distraction from the missing funds. This romance collapses following a devastating betrayal. In turn, this fall precipitates the recovery of the lost £1,000 and the hard-won wisdom that Mike has regained something that once was lost.

In execution, it’s an album both epic and slight. Good pop practice is to treat the concept in concept albums lightly, but this isn’t the Mike Skinner way. A Grand Don’t Come For Free proves that rule. Pop is always easier at beginning stories than resolving them. Here, tracks like ‘Get Out Of My House’, ‘What Is He Thinking’ and the eight minute resolution ‘Empty Cans’ are heavy with exposition and plot at the expense of quality.

Of course, some of the album’s high points manage to fuse the storytelling demands of the wider project with what can realistically be achieved within a single song. “Blinded by the lights” is a phrase that Skinner first used during early single ‘Let’s Push Things Forward’, its recycling as a song name here suggesting some significance, a resonant memory perhaps, for its author. Here, a sluggish beat introduces an unusually murky synth line which stutters slowly like a malfunctioning strobe light. Only a lonely and angelic chorus vocal by longstanding session vocalist Jackie Rawe lets any light in. Though the song serves to seed the plot point of character Simone’s infidelity, its narrative is universal and compelling: the upper that becomes a downer, pingers that taste like hairspray and a night out (“rammo in the main room”) that collapses into MDMA paranoia.

There’s a breezier take on nightlife in ‘Fit But You Know It’. The track, which would be the lead single from the album, begins with a thrillingly yobbish Telecaster riff which cheekily cribbed from that year’s ongoing NME-endorsed indie revival (the same ‘Club A Go Go’-chug would reappear on Girls Aloud’s ‘Biology’ single the next year.) The track harmonised with the cheery and triumphant flavour of mainstream British misogyny in the early 00s. “You girls think you can just flirt and it comes to you,” says Skinner in a line that sums up the song’s sneery attitude to its female subject. Speaking to The Independent in 2020, Skinner pondered that, in “the context of FHM culture and Nuts magazine, it’s probably a bit more woke than that, but definitely less woke than now.” This comparison – to the publications behind High Street Honeys and breezy, celeb-led jokes about domestic violence – is a low bar to limbo under in the name of self-reflection.

The song where Skinner most utilised the ideas of Sheila Davis would also be his biggest hit, and one of the defining British number 1 singles of the decade. “The emotion that is at the heart of the story is never explicitly described,” writes Skinner in his memoir of ‘Dry Your Eyes’, “there’s not one mention of love, it’s only pointed to by physical actions.” Watch how in the song he’s almost always describing what the hands of both parties are doing. “People feel these emotions much more strongly than if you’d referred to them directly.”

‘Dry Your Eyes’ was sculpted around a string hook from a CD of royalty-free samples. With its strummed acoustic guitars, orchestral arrangement and plainspeaking chorus, it’s as middlebrow as a midweek crime drama and closer to the big sad lad ballads of ‘Wonderwall’ and ‘Why Does It Always Rain On Me?’ than anything on Original Pirate Material. There’s even a huge dollop of Take That’s ‘Back For Good’: heavier on the Gary Barlow than it is on the Gary’s or the garage. As Ben Thompson clocked in an Observer interview published just before the album’s release, the rapper is already referring to it privately as “the one which’ll get us on regional radio.”

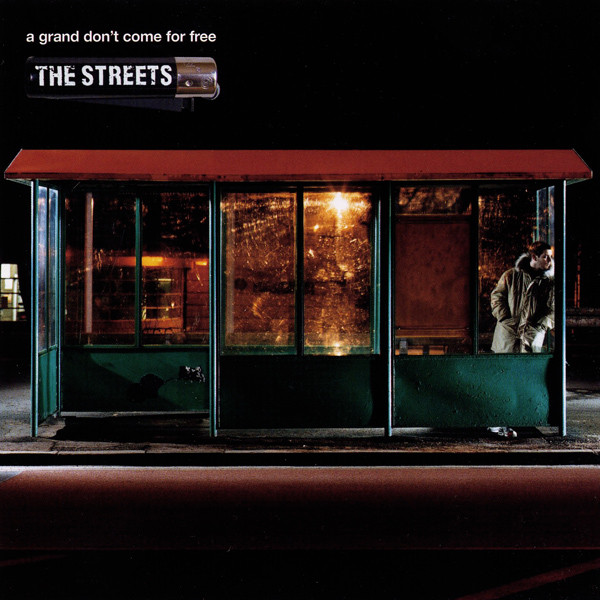

It did. When A Grand Don’t Come For Free was released on Monday 17 May 2004, it debuted at number 2. This was a healthy chart position against the imperial Hopes And Fears by Keane. Unusually for that kind of record, though, it held its own and just kept selling. On 3 July, it finally ascended to the number 1 slot.

Those who bought it wanted more: even Original Pirate Material suddenly began shifting serious units and entered the Top 10 for the first time on 10 July. Then, on 19 July, came the CD single release of ‘Dry Your Eyes’. This changed everything. The single surged past ‘Lola’s Theme’ by Shapeshifters and Rachel Stevens’ ‘Some Girls’ to the number one slot. Over at the album charts, A Grand Don’t Come For Free suddenly became number one once again.

“We were in France in the countryside, I think it was a day off on tour,” told Skinner to GQ in 2023, “and a big group of us walked into this village to buy an ice cream. And I just remember thinking: I’m number one in the charts. And it was amazing, because it’s what all musicians want, really – well, musicians of my generation anyway. Being on Top Of The Pops and having a number one.”

Mike Skinner might have been the last person to experience breaking through the British pop monoculture in the way that it had existed intact in 1964, 1974, 1984 and 1994 but then didn’t at all in 2014 or 2024. The Top Of The Pops that he broke through to was an institution in terminal decline, a niche pastime enjoyed by less than three million punters and only two years away from its eventual euthanasia.

So what happened? When Skinner beat Will Young, Lemar and Morrissey to the 2005 Brit Award for Best British Male, he’d already left the ceremony and was back at his Stockwell gaff. Some of what he was getting up to became evident the next year, when he released The Hardest Way To Make An Easy Living. A deliciously ungrateful album of reportage from the front line of mid 00s tabloid fame, it’s an album that bites the hand that feeds in the iconoclastic tradition of Dexys’ Don’t Stand Me Down. Inconveniently, it’s significantly less good than this album though. Mike Skinner’s audience had expected to be able to see themselves in Streets records, and instead were greeted with a rich man wondering aloud about cameraphones crushing his vibe when he tries to snort cocaine in public, and whether Warners were on top of counterfeit Streets merch.

2008’s Everything Is Borrowed holds a couple of the strongest and most committed moments of Skinner’s career – a curiously zen record written with a brief to eschew all references to modern life – but the culture had moved on decisively. “Such a self-whittling to near nothing of a Major Artist of the Decade has rarely been witnessed,” wrote Simon Reynolds at the end of that decade, arguing that Skinner had “this incredible self-erasing man effect.” This has summed up the critical consensus on Skinner’s trajectory to this day, and is implicit in 2022’s numerous Original Pirate Material anniversary pieces.

But what if we’ve been misunderstanding Skinner for twenty years?

There’s a YouTube clip that resurfaces on social media occasionally featuring Mike Skinner circa the release of Original Pirate Material. Ostensibly being interviewed in a backstage area, the unusually sweaty and chatty rapper is bending the TV presenter’s ear about how Peter Mandelson* went mad in the 1980s, and began hearing voices telling him to kill Tony Blair. “But he came back from it,” says Skinner, “he came back from it, man.” Then there’s the payoff: without missing a beat, Skinner walks immediately on stage after finishing the anecdote to launch into a gig as the crowd go wild. It’s an incredible piece of footage, but perhaps what attracted Skinner to this shaggy dog story was an implicit understanding early on that he himself would have a career that defied conventional logic in its trajectory.

Plenty of artists talk a good game about being the kind of people who like to try out new things and move on without looking back, it’s usually savvy marketing cover for art that clearly proves the opposite. Mike Skinner, though, is legitimately one of those individuals: his career shows a pattern created by a focused and ambitious obsessive who can only work to highly specific briefs. That’s all Original Pirate Material was, a man working out whether UK garage sounds could be fused with lyrics that reflected street-level British quotidian life. Those were not songs he had been plugging away at for years in small venues and clubs. The only way he could follow it up? Another project, another tight concept.

“It takes a lot of mental strength,” wrote Skinner in a Reddit AMA in 2021, “to keep making good decisions knowing your best work is long behind you.” That’s a hard pill to swallow, but once you do that?

In the 2010s, after wrapping up The Streets following a neat ten years and five albums, Skinner made a bassline club night, documentaries for VICE, a rap and news podcast called Peak Times, the Mike Skinner Ltd label producing and managing British hip hop acts, penned a memoir, dropped standalone tracks and collaborations throughout, even learning to write, direct, star in, edit and fund a film which was eventually released last year. Sure, he’ll tour as The Streets now, and give audiences that thing they want, but read the interviews and it’s almost always to finance some project or enterprise. It’s surely more interesting than the polite plateau of diminishing returns, back to basics projects and purported returns to form.

One of those little projects just happened to make him the most influential British musician of the 21st century, exerting an obvious and primary influence over artists including Arctic Monkeys, Kae Tempest, Sleaford Mods, The 1975, Lily Allen, Little Simz, Idles, Plan B, Self Esteem, Fred Again and more. His influence on UK hip hop is slight, but it’s weighty amongst the kind of artists that in 2004 would have been the kind of broad, post-Britpop, regional radio audience that A Grand Don’t Come For Free was courting.

A few months after A Grand Don’t Come For Free, the highly influential race and culture scholar Paul Gilroy – author of the landmark 1987 study There Ain’t No Black In The Union Jack – began to pioneer the term ‘convivial culture’ in his newly released book After Empire. Gilroy argued that in the face of the continuation of racism and imperialism through the political culture of New Labour and the ‘war on terror’, Britain did in fact have an unruly and ordinary multiculturalism thriving organically and unnoticed in its urban centres. In the chapter Has It Come To This?, Gilroy convincingly posited Skinner as a powerful example of that culture, framing The Streets as “poetic attempts to make the country more habitable by giving value to its ability to operate on a less-than-imperial scale.” In 2024, critic Skye Butchard has identified a defining UK sound and style in diverse and often non-white British artists applying the signs and signifiers of Britpop to modern takes on jungle, leftfield pop and club music. The early work of Mike Skinner popularised a striking prototype of this fusion.

This, for Mike Skinner, is no small legacy. And what’s more, he probably wouldn’t have done it without the work of Sheila Davis. He knows it. “Successful Lyric Writing is still under the sofa in my studio,” wrote Skinner in 2012, “I’ve got her The Craft of Lyric Writing on my iPad.”

[*There is nothing in Peter Mandelson’s biography or elsewhere to suggest that this happened, and it seems likely Skinner has the politician mixed up with someone else, although during the week that ‘Dry Your Eyes’ reached number 1, the New Labour government announced that the twice-resigned Mandelson would be returning as EU Trade Commissioner. He came back from it, man.]