“Under the brown fog of a winter dawn

TS Eliot, The Waste Land, 1922

A crowd flowed over London Bridge

I had not thought death had undone so many

Sighs, short and infrequent, were exhaled

And each man fixed his eyes before his feet”

“London is just grey echoes, Bad memories, and dreams, And someone far away….desperate people”

Patrik Fitzgerald, ‘Grey Echoes’

“They’re disturbing and that’s the best quality you can have as a songwriter.”

Liza Minnelli on Pet Shop Boys, 1991

“Don’t push me ‘coz I’m close to the edge

Grandmaster Flash and The Furious Five, ‘The Message’

I’m trying not to lose my head

It’s like a jungle sometimes

It makes me wonder

How I keep from going under”

In 1983 Neil Tennant was at his cousin Richard’s house in Nottingham. They’d stayed up late to watch a James Cagney movie on TV, one of those gangster flicks where the anti-hero crawls out of the gutter by criminal means only to slide back down during the final scenes. Afterwards, around 1AM, while trying to get to sleep in a single bed in a small room, words came to Tennant like shots fired from a pistol:

‘Sometimes you’re better off dead,

There’s a gun in your hand,

And its pointing to your head’

He scribbled the results of this flash of inspiration down onto a piece of paper; they were the opening lines to a rap he would complete on the floor of his King’s Road flat back in London. Cagney may have provided the trigger but Tennant’s spoken word saga, entitled ‘West End Girls’, was, he’d later say, “completely inspired” by Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five’s ‘The Message’. A top ten hit in the UK the previous autumn, ‘The Message’ was a hip hop game-changer, a shift from party rhymes to brutal street-level reportage, more ‘Living For The City’ via Gil Scott-Heron than ‘Rapper’s Delight’. Chronicling a hellscape of “broken glass everywhere”, piss-soaked stairs and rat and roach-infested apartments, ‘The Message’ was ferocious.

Real-life details (the 1980 NYC transit strike) were fed into the noir horror, grimly culminating in a prison cell with body swinging “back and forth”. But Bronx tough stuff collided with Downtown dancefloor fruitiness, mixing Zapp, Byrne/Eno and the Tom Tom Club. While Grandmaster Flash’s collective were initially reluctant to record ‘The Message’ (only rapper Melle Mel actually appears) it was a Tennant favourite during his first year at Smash Hits, where his love of hip hop earned him the nickname Chilli T.

Tennant conceived his own tale of inner-city pressure in an American accent rapping ‘West End Girls’’ to his musical partner Chris Lowe at Ray Roberts’ Camden 8 studio. Yet it came straight from the London he’d lived in since 1973, subtly referencing Gerrard Street’s Dive Bar, a gay basement drinking den Tennant and Lowe would frequent on strolls through Soho. Many would later think that ‘West End Girls’ was about sex workers, but for Tennant it was “about class, about rough boys getting a bit of posh” prompted by seeing skinheads roaming Leicester square. East meets west in a drama of opposites, reflecting city life’s endless extremes. It’s a dark, paranoid place of shadows and whispering voices, full of demands and desires, be they sex, money, drugs (“how much have you got?”) Faced with myriad pressures and distractions (“too many choices”), hearts harden like stone or shatter like glass. Relationships are fragmentary, rootless and disposable (“no future… no past”). Beneath the escapist lure of the metropolis lies only an inescapable cold reality, “a dead-end world”.

This bleak vision recalled T.S Eliot’s ‘The Waste Land’, another masterpiece of urban disenchantment, “a heap of broken images” flickering with lonely souls in an “unreal city”, a fractured response to WW1’s ravages. Tennant confessed that he “never really understood it” but ‘West End Girls’’ emulated the chattering collage of different voices, the mix of demotic and highbrow. Lines that sound snatched from overheard dialogue (“We wanted our records to reflect the world around us,” Tennant told the BBC) are juxtaposed with Russian history (Lenin’s journey from west to east in a sealed carriage, a detail lifted from Edmund Wilson’s To The Finland Station). The high glam in Tennant’s record collection already bore traces of ‘The Waste Land’ from Lou Reed’s Transformer (‘Goodnight Ladies’) to Bowie. Bowie hadn’t read the poem when Burroughs saw echoes in the singer’s lyrics when they met in 1973. ‘Sweet Thing/Candidate’ suggested by 1974 this state of affairs had changed.

The sharp eyes of pop past had seen the bruising reality beneath the romantic metropolitan promise. In1966, the capital’s swinging scene was eviscerated by The Kinks (‘Dead End Street’, ‘Big Black Smoke’) and Bowie (‘The London Boys’). During punk, it was a place of high-octane danger, full of “Hades ladies dressed to kill” and “dagger glares” on X-Ray Spex’s ‘Let’s Submerge’, posing a perpetual threat on The Jam’s ‘A Bomb In Wardour Street’ and ‘Down The Tube Station At Midnight’. Tennant and Lowe loved Soft Cell’s 1981 single ‘Bedsitter’ too, exposing the alienation away from nightlife’s razzle-dazzle.

A year later the synth anti-pop of Patrik Fitzgerald’s ‘Grey Echoes’ was even sadder, portraying a London of false hopes and bad memories. Like ‘Opportunities’, ‘West End Girls’ had been penned around the time of the Tory’s 1983 landslide, when the Thatcher-era truly arrived, when the city, specifically London, became the locus for the dog-eat-dog ethos.

Besides ‘The Message’, 1982 had been full of Tennant/Lowe signposts, ‘Planet Rock’, Sharon Redd’s ‘Never Give You Up’ and a 12-inch Lowe had bought, ‘Passion’ by the Flirts, from NYC producer Bobby Orlando. Tennant raved about its cold shower-inducing “hot disco ignition” in Smash Hits as he salvaged Orlando productions from the magazine’s dumper box. They strove to recreate their mutual hero’s pulsating post-disco electronics, which could be heard pumping out at Heaven. Tennant eventually used an NYC interview with Sting, while The Police were playing Shea Stadium, as an opportunity to meet Orlando, on 19 August 1983, exactly two years after first bumping into Lowe in a hi-fi shop on the King’s Road. Enthusiastic about recording the duo, then called West End, he went on to sign them to a production deal.

The music for ‘West End Girls’, Lowe’s squelchy synth bass, came together just days before the pair crossed the Atlantic to work with Orlando; the rap was initially committed to tape with a rhythm track of percussive clatter. As it evolved, a sung chorus emerged and Tennant ditched his ‘corny’ US accent for an avowedly English one. This distinguished it from previous white rap, which had veered from Blondie’s sublime US chart-topper ‘Rapture’ to Rodney Dangerfield’s comic ‘Rappin’ Rodney’. Where Wham! aped current American styles, ‘West End Girls’ seemed to reroute rap back to WH Auden reciting ‘Night Mail’, back to Edith Sitwell, as if they’d played an integral role in hip hop evolution.

An Orlando-produced version was cut at NYC’s Unique Studios. His Emulator synth was central, providing atmospheric Gregorian choirs and Marcato strings. Samples came thick and fast, from broken glass (a nod to ‘The Message’) to the drum sound from Bowie’s ‘Let’s Dance’ to James Brown. Familiar Orlando motifs such as cowbell and that synth-bass placed ‘West End Girls’ firmly on the dancefloor. It wasn’t alone. New Order’s ‘Blue Monday’, another UK single hot-housed in US clubland with an Emulator choir, was released earlier that March. Tennant and Lowe arrived that autumn in a city exploding with dance energy, from Madonna’s debut to Shannon’s September Freestyle innovation, ‘Let The Music Play’. They sampled NY nightlife from the Paradise Garage to Danceteria to Tennant’s favourite, Area, where he found himself standing next to Warhol at the bar. He multi-tasked, dividing his time between recording sessions and launching Smash Hits’ US analogue, Star Hits.

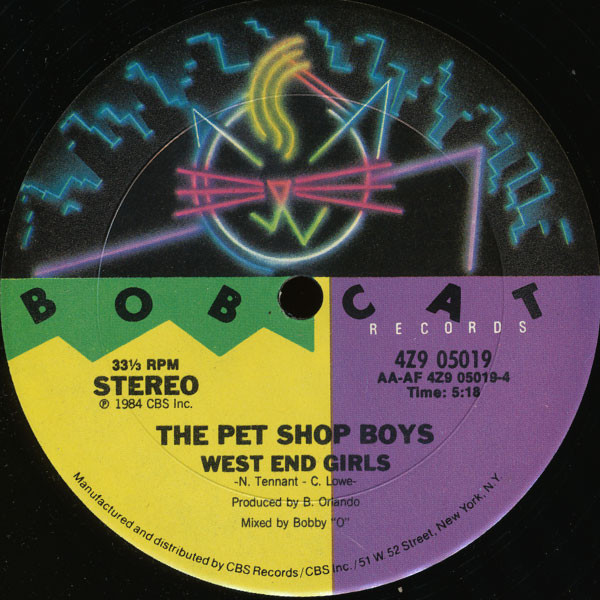

On 9 April 1984, ‘West End Girls’ was released bearing their new name Pet Shop Boys, an amalgam of US dance acts like B-Boys and Peech Boys and something “weird and English”, although, quite simply, Lowe’s Ealing flatmates worked in a pet shop. Issued on Orlando’s Bobcat label in the US, the UK 45 came out via Epic after A&R man, Gordon Charlton had overheard their music on a tape Eric Watson, Tennant’s friend and Smash Hits photographer had played during a shoot. A hit in US West Coast clubs, peaking at 7 in Belgium, reaching the French top 30, it made little impact back home. Bizarrely No.1 magazine preferred the flipside, a vocoder-heavy electro theme for the new moniker. As 1984’s premier league (Duran, Frankie, Wham!) held the top spot and Hi-NRG and Black America filled the charts, ‘West End Girls’ was lost, sandwiched between Soft Cell’s swansong This Last Night In Sodom in March and Bronski Beat’s ‘Smalltown Boy’ that May.

They were dropped from Epic but there was another Pet Shop Boys/Orlando single released outside of Britain called ‘One More Chance’. But the duo became increasingly frustrated with their slow progress working with the producer. “Nothing seemed to get finished,” Tennant would later say, telling No.1 Orlando had become distracted by litigation with another act. Extricated from their contract with him, the producer settled for royalties on subsequent albums.

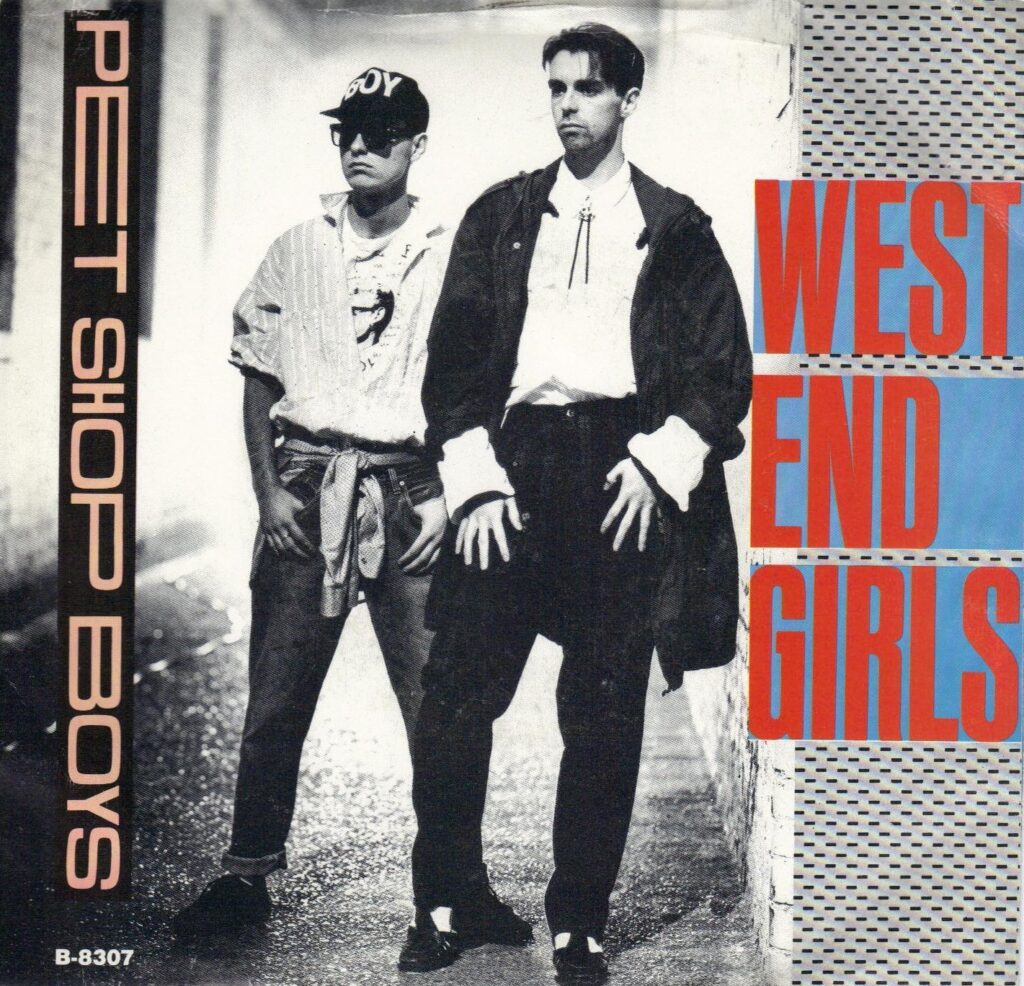

‘West End Girls’ striking sleeve had come from the team responsible for Frankie’s covers, XL Design run by Tom Watkins, a blast from Tennant’s past at Marvel Comics. Watkins had borrowed a Spiderman costume from him for his cartoon glam act Giggles.

In October 1984 they signed a deal with Watkins’ Massive management company, certain he could sign them to EMI. By March 1985, he’d done just that, though they opted for Parlophone, considering the main label “naff”. With the advance matching his Smash Hits wages, Tennant quit the magazine, declining the opportunity to fill departing editor Mark Ellen’s chair, also turning down another offer to be The Sun’s Bizarre pop columnist.

Released on 1 July 1985, Pet Shop Boy’s Parlophone debut single, ‘Opportunities (Let’s Make Lots Of Money)’, produced by Art of Noise’s JJ Jeczalik and Nicholas Froome cost £40,000 to make. The Fairlight-sculpted single, assembled over three weeks at various London studios, stalled at 116, its dark satire about hapless schemers and money making at odds with a summer basking in Live Aid glory. PSB then turned to producer Stephen Hague, whose name had appeared on records by World Famous Supreme Team and Rock Steady Crew (he’d received his first solo production credit that June with OMD’s ‘Crush’). “Nobody wanted us to work with him,” Tennant recalled years later. Despite EMI and Watkins’ lack of enthusiasm, he was a natural fit. With Malcolm McLaren on 1984’s ‘Madame Butterfly’ he’d blended grandiose opera with R&B modernity. As much a fan of Todd Rundgren and Beach Boys as he was Kraftwerk, he shared PSB’s tastes while imbuing them with fresh sonic nuances.

As an experiment, they remade ‘West End Girls’ with Hague; even though they didn’t own the original masters, they wanted UK audiences to hear it. The recording took place at London’s Advision studios on Gosfield Street, where both Bowie and Kate Bush had worked, and Soft Cell’s Tainted Love had been made. Orlando’s version had been completed in just four hours; Hague’s redo was finessed over five days. Slowed down to foreground lyrical storytelling, it was less dancefloor-focused; darker, more ‘filmic’. Moodier elements from the original remained (choral wash and Marcato strings), random novelty samples, which Hague deemed ‘camp’ and ‘cheesy’, were dialled down.

The Oberheim DMX supplied the beat, while a machine-generated conga part was played live in the studio. The Emulator still dominated, the sampling synth models I and II were both used, not just for those choral/string sounds but a trumpet solo, Hague playing ‘wrong’ notes like a jazz player. This expansive sound design meant the song now resembled Bowie’s ‘Big Brother’ more than ‘Blue Monday’. Another addition was Helena Spring’s vocal support, at turns stoic and soul-searching, like a glamorous gangster’s wife stuck in an unravelling crime caper. Even her voice was fed into the Emulator, her highlights sprinkled throughout. .

For the fat, sexy bass part, MIDI was deployed, the state-of-the-art digital interface syncing three synths together, a Yamaha DX7, Roland Jupiter 6 and that trusty Emulator II.

The final masterstroke came late in the sessions, Hague taking his Professional Walkman, using Dolby C, out onto the street to record city noise as the rain poured down; passing traffic, high heels on pavement. Opposite Advision was Wham! manager Simon Napier Bell’s offices, where fans would congregate outside, their indecipherable voices captured on the recording . From the pneumatic drills that interrupt Lovin’ Spoonful’s ‘Summer In The City’ to the speeding trains opening Eurythmics’ ‘This City Never Sleeps’, evoking urban life’s hustle and bustle had been central to metropolitan pop. Hague’s street sounds became the perfect intro for ‘West End Girls’, accompanying hi-hats, a bass drum and Emulator strings, luring the listener into the drama with vivid authenticity.

The ‘three dimensional’ rich sonic detail now mirrored the multi-layered urban panorama of Tennant’s words. Those were refined too, the former editor chiselling four verses into three, losing that clunky Stalin-stallin’ rhyme, transforming a great lyric into pristine pop poetry. The remake also reflected the dazzling, century-spanning scope of influences that had been poured into this slender pop vessel, from Cagney noir to ‘The Message’s street life to ‘The Waste Land’s stark modernism.

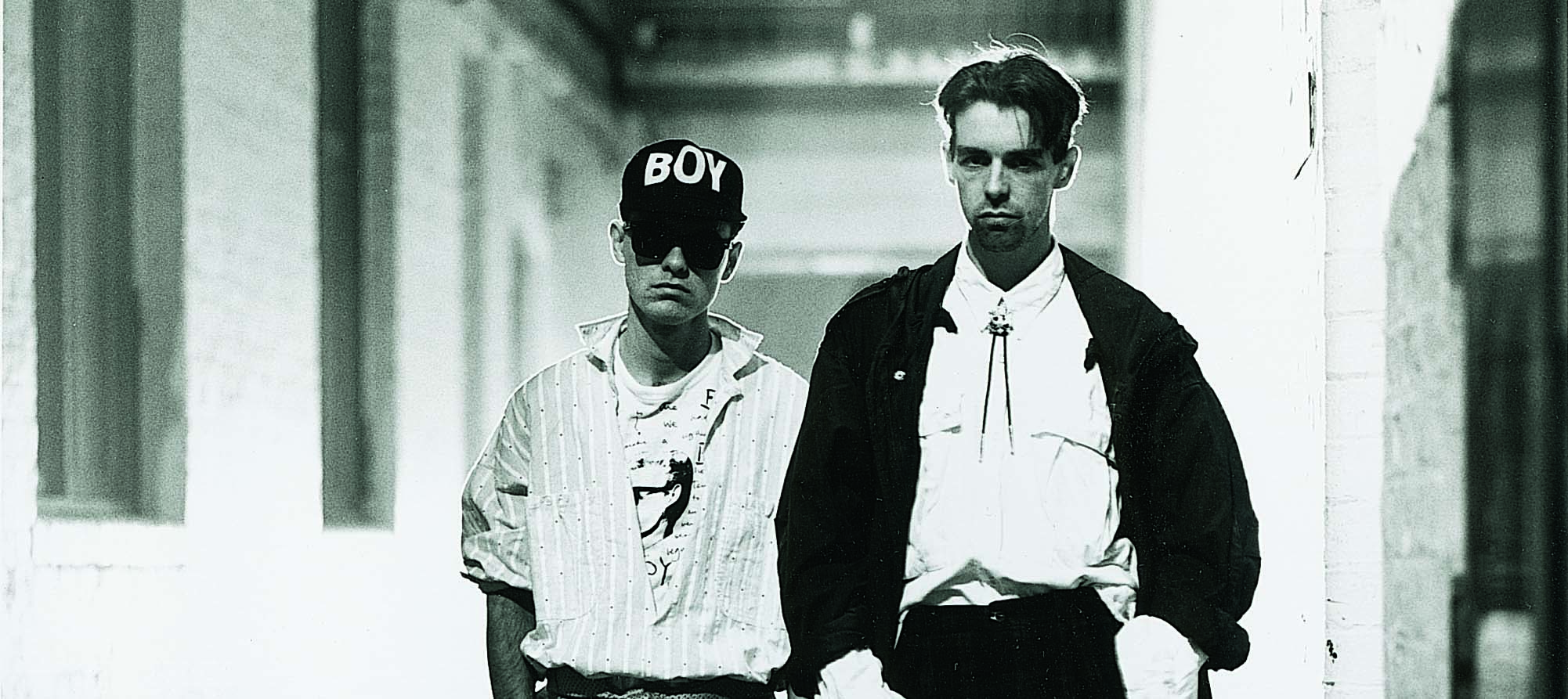

Pet Shop Boys insisted it was the next 45 regardless of doubts from Parlophone. For the video, Watkins instructed directors Eric Watson and Andy Morahan to shoot a London travelogue. Commencing at 6 AM they filmed areas like Aldgate, then followed Tennant and Lowe through markets, along the Thames to Waterloo Station’s concourse. These street scenes were interspersed with solarized aerial views of landmarks like Tower Bridge, redolent of Bowie’s David Mallet-directed ‘Ashes To Ashes’ clip. As much a snapshot of 80s London as films like The Long Good Friday and Mona Lisa, neat touches abounded, from creepy opening shots of shop-front child mannequins to a tramp walking beside them to Lowe semi-boogying as he catches his partner up. With Tennant in his £400 Stephen Linard overcoat and Lowe in casual clobber, PSB style had evolved.

They’d previously hinted at their image’s mild subversion talking to No.1 in the 10 August 1985 issue. “I’m supposed to be the older character, slightly business looking, shady and odd,” said Tennant, while laddish Lowe was “street and naïve, easily led”. Tennant added that while his partner looked like he was “waiting to be led astray by me… the reverse is true!”

To the untrained eye, this was just another odd couple synth duo, their smart/dressed down normality breaking with the garish excess and supersized mullets of the high 80s. But those more conversant in gay culture saw a visual dynamic fashioned from a demi-monde of hustlers and Johns, executive realness and rough trade, Noel Coward gent and Joe Orton tough.

Released 28 October 1985, ‘West End Girls’ entered the charts at 80, and slowly began to climb. Tom Hibbert’s s review in Smash Hits’ 6 November issue evocatively conjured the cine-pop mood.

“A tumble through Soho in the seedy, wee, wee small hours accompanied by the kind of jaundiced horns – more often found on soundtracks of films about Hollywood actresses hitting the bottle and cracking up with mascara running down their faces (Valley Of The Dolls springs to mind). Set against this, the electronic beats and demi-rap (The Message without the baseball bat) creates an atmosphere of danceteria sleaze that’s almost sinister. Brrr.”

On 5 December they made their TOTP debut, Steve Wright introducing “an unusual song by an unusual band”, Mike Smith describing them after as “ethereal”. During its ascent, multiple formats trickled into record shops, including a Mastermix in a stunning ‘Blue Monday’ meets Ettore Sottsass sleeve, its blocks of colour and dash dots being their first collaboration with designer Mark Farrow. It was nestled in the top ten as 1985 ended. By January 1986 it had dislodged festive chart-topper Shakin’ Stevens, becoming the year’s first new number one (“Don’t look triumphant”, Lowe urged Tennant as they performed on TOTP). Staying at the top for two weeks, ‘West End Girls’ would become a global sensation. By May it sat atop the US Billboard Hot 100, also hitting no.1 in Canada, Finland and New Zealand and the top ten in multiple territories, a London song for “every city and every nation”. It fitted snugly onto Please, recorded as it gathered momentum, back at Advision with Hague, with its tales of escape and desire.

‘West End Girls’ reflected a pop zeitgeist oscillating between sonic luxury (the same month saw the release of ‘Slave To The Rhythm’ and ‘Cloudbusting’) and hard-hitting realism. Simply Red addressed poverty on ‘Money’s Too Tight (To Mention)’, The Blow Monkeys tackled AIDS on ‘Digging Your Scene’. As the top-tier acts of the 80s first half fragmented and imploded, aspiration was tempered by a topicality that had been creeping back in since 1984. Soon zany, colourful pop mags like Smash Hits would feature Anti-heroin ads and warnings about AIDS.

Nobody would capture this tension of luxury and heartache in the second half of the 80s, and maintain it, better than Tennant and Lowe. They rerouted British pop back to the ideas-driven year of 1981 – the year they first met – when Human League and Soft Cell tilted electronic pop towards clubland, when ‘New Life’ rubbed shoulders with ‘Ghost Town’. But their multi-layered approach and sensitivity to cultural context placed them in the great British art-pop tradition of Bowie and The Beatles, giving mass appeal to the arcane and underground. ‘West End Girls’ envisioned the future of dance too. Fast forward to 1991’s Blue Lines by Massive Attack, a sample-heavy, ‘filmic’ UK twist on US hip hop and it is not such a stretch to see ‘West End Girls’ as a stepping stone towards the Bristol sound.

Pet Shop Boys would continue to chronicle London life with melancholy and moral fury on 1987’s ‘King’s Cross’ and 1993’s ‘The Theatre’. But these Tory-era narratives would be joined by songs hymning the pre-AIDs ‘Land Of Lost Content’ wistfully recalled in the magic autobiography ‘Being Boring’, and now ‘New London Boy’ on the lovely, stirring, elegant Nonetheless. But ‘West End Girls’ remains the ultimate ode to how thrilling and unforgiving life in the capital can be, “all the promise it held”, as Tennant said, as well as all its potential perils. It’s been covered by everyone from East 17 to Sleaford Mods, who donated proceeds from their version to a homeless charity, proof that living in the city during tough times is always, to quote The Message, living “close to the edge”.

![Pet Shop Boys - West End Girls (Official Video) [HD REMASTERED]](https://thequietus.com/app/cache/flying-press/24e1478685f37cf5e8abb302de4bb6f3.jpg)