I remember quite clearly the moment I decided to become a vegetarian. I was in my late teens, on holiday with my family on the Isle of Skye. We’d spent the day driving around, occasionally catching a glimpse of deer through the raindrops: and when we got back to the guest house, we found that the menu for the evening was venison. I was never a particularly adventurous eater, but 35 years ago anything other than beef or pork seemed pretty exotic. And meat was always very well done – if it wasn’t black on the outside it hadn’t finished cooking as far as I knew. So to be confronted with flesh of a decidedly pink hue, swimming in what looked less like gravy than blood, was the last straw.

Thoughts of giving up meat had been buzzing around for a while, and even though I barely ate vegetables at all – potatoes and carrots were about as healthy as I got back then, and I’d still routinely turn my nose up at anything green – I was coming to the conclusion that I could no longer justify eating dead animals. If it was up to me to kill it, it would still be out there, roaming around in the field: and that’s been the rule of thumb I’ve stuck to since. I’ve never been a hunter or a fisherman, never felt I had the right to take another life; and until I get to the point where I’m so hungry or have undergone so complete a change of mindset and worldview, then I didn’t think – still don’t – that I can eat meat without being the worst kind of hypocrite. (I’ve no problem with others choosing their own positions here, and I’m not a zealot or an evangelist for the cause of vegetarianism: to each her or his own. But that’s where I drew – and still draw – my line.)

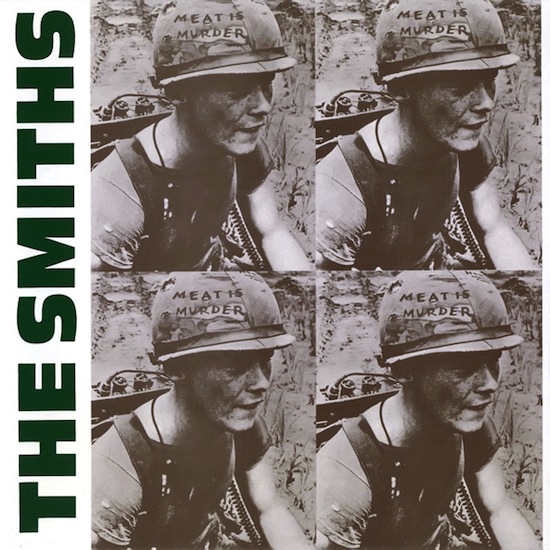

The Isle of Skye venison was the final decisive factor, but there were two other key elements in me making this change. The first was being in a relationship with a vegetarian who, while never quite going so far as to try to get me to stop eating meat, certainly got me thinking about whether it was something I really felt like I should still be doing. And the second, which worked in exactly the same way, was the second Smiths LP.

Just as Noel Gallagher pointed out when talking to Jude Rogers in these pages recently, Meat Is Murder was a deeply political album, even though it didn’t come across like one:

Noel: Billy Bragg never interested me in the slightest. … Morrissey interested me more, because when you were listening to his music, he wasn’t beating you over the head with his political views.

Jude: Apart from…

N: [interrupts] OK, apart from ‘Meat Is Murder’.

J: Which isn’t exactly their best song.

N: I think it’s their best album. But I’m not a vegetarian, if that’s what you mean. They’re not beating you over the head with their political views. You can make your own mind up, can’t you?

You could indeed. But you were left in no doubt that this was a decision you had to actively take. Until February of 1985, whether I should eat meat wasn’t really an issue I’d ever given a great deal of thought to: it was just something I did without thinking. And while I can’t say that Morrissey was the difference between me giving up meat and not, this record was a significant part of the process that led to a decision that made a huge difference to how I’ve lived my life for the three decades since. There have been other records that have opened my eyes to subjects I’d never properly thought about before, and other artists whose political and social views have helped form the background to decisions I’ve taken or attitudes I’ve chosen to adopt – but I don’t think any one record has had such a considerable, sustained and existential impact on my life.

That fact seems all the more bizarre when I consider that, of the nine songs on the record, the title track is by far my least favourite. By placing it at the end of side two, it’s also been the easiest one to skip, and as a result is probably the track on the album I’ve listened to the least. This may be because of a sense of guilt it helped inculcate right at the start, and if that’s the case then that’s testament to its power, and forms at least some sort of explanation of its impact. Bits of that come from the sound of the piece: the juxtaposition of the jarring, discordant, treated piano hits, the screaming of what one supposes is an industrial saw, the voice of the cattle and Johnny Marr’s plaintive, maudlin melody isn’t meant to uplift and captivate – it’s designed to be part elegy and part horror-film soundtrack.

It’s also far from Morrissey’s best work as a lyricist. It’s clear he cares deeply, but he isn’t at his best writing protest songs (acoustic guitar notwithstanding). You can take it apart and find fault with the logic ("It’s death for no reason, and death for no reason is murder," he sings: well, not entirely – if a double-decker bus killed the both of us, to die by your side would most likely be a tragic accident rather than murder) but to do so is to miss the point. You’re supposed to be repulsed, so if you’re not keen to listen repeatedly, that may simply be evidence of the job being done to perfection: and if the lyrics stick in your mind – for any reason at all – then the song has achieved what it presumably set out to do. So one of the band’s least appealing and ostensibly least successful songs actually stands as arguably their single most powerful moment.

Less difficult to explain, perhaps, is how come it was a record by The Smiths which could make such a significant – literally life-changing – difference. Plenty of artists made records which have prodded listeners into awareness of political issues that they’d go on to champion; musicians have proved to be a very effective means of getting people to register to vote or raising money for different social and political causes, from striking miners to debt relief for entire nations. Yet it’s still difficult to think of many bands who have succeeded in getting listeners to make lifestyle changes that lasted longer than a season. If there are any good examples – and please feel free to mention personal favourites below – chances are that most of them had built up more of a track record with listeners than Morrissey, Marr, Joyce and Rourke had done by early 1985. Six singles – the last of which was the reissued b-side of the fifth – and one-and-a-half albums was the sum total of their contribution to most listeners’ lives at this stage. There had of course been gigs, but relatively small ones by today’s standards: and to those of us who lived some distance from the major cities that independent bands could then tour, those were not a factor.

The things that gave The Smiths the capacity to change lives were the same set of factors that ensure their records remain arresting and remarkable all these years later. Morrissey’s lyrics spoke about real lives with an honesty and a clarity that rock and pop often shied away from: here was someone writing about heartbreak and isolation not as mythic subjects that somehow glorified the sufferer, but as the all-too-real consequences of the everyday. You didn’t get the sense, as one sometimes does from songwriters, that they were trying to make it sound like they were doing all this to provide escapist or aspirational entertainment – the characters Morrissey wrote about were you, or the folks around you, or the people you thought you might one day be. They looked like a band, they had that indefinable star quality, and there was the strangeness of Marr’s music and the ambiguity around Morrissey’s in-song personas that meant you were never thinking they were just the same as you – but they were a lot nearer to being people you might know than the rest of the pop world of the mid-1980s. So as great as the music was, and as unique and untouchable as parts of it undoubtedly were, these records felt like they could have sprung from you, your mates, your wider social circle. As Thom Yorke put it, introducing Radiohead’s cover version of the opening track from Meat Is Murder during a 2007 webcast, "this is about when we were younger – but we didn’t write it." And in Marr’s capable hands, each lyric was arrowed into your head and your heart with the most appropriate and individual accompaniment, music reinforcing the lyric’s emotions and making the songs impossible to not have some kind of personal reaction to and relationship with. These songs became your friends.

The decision the band had come to about production by the time they made Meat Is Murder was important, too. Their first album had had to be completely re-recorded and nobody seems to have been overjoyed with the results. They stuck with producer John Porter right up to the final track made before the Meat Is Murder sessions began, and given how tremendously that song turned out, you do wonder whether the relationship was ended just when it had started to find its feet. Porter’s input to ‘How Soon Is Now’ proved critical: he encouraged Marr to locate the arrangement that worked and the final mix, which he oversaw, still ranks as one of the finest moments of 1980s music – hell, it’ll probably be in many people’s all-time Top 20. Yet the band decided to go it alone, and produce their second album themselves, with help from an engineer (Stephen Street). It could’ve gone wrong in a number of different ways, but what Marr and Morrissey may have lacked in studio experience they more than made up for in musical knowledge, self-belief, and a certainty in what they were doing and how it ought to sound. A brief hand, here, for Joyce and Rourke: according to the credits on every Smiths record they weren’t involved in writing the music, and their part in the court case that dominated proceedings after the band broke up will have soured many fans to them and cost them sympathy and empathy. But even Morrissey, as he despairs of what he considers their treachery in his book, acknowledges their particular and singular excellence: and on Meat Is Murder they came into their own giving these songs power and poise, perfectly preparing and solidifying the bedrock on which the songs were to be built.

‘How Soon Is Now’ was, infamously, rejected as a single by Rough Trade; in his autobiography, Morrissey tells of being brought down from cloud nine to terra firma when label boss Geoff Travis conspicuously failed to be as knocked-out by the track as the band were. That initial decision to relegate the song to b-side status was soon reversed – the track, included on the ‘William, It Was Really Nothing’ 12" and on the brilliant Hatful Of Hollow singles/b-sides/outtakes collection in 1984, was voted Number One in that year’s Festive 50, compiled by John Peel from listeners’ lists of their favourite three songs of the preceding 12 months, and Rough Trade bowed to the inevitable by making it a January a-side ahead of February’s release of Meat Is Murder. That it became the de-facto lead-in single to an album it doesn’t appear on and wasn’t made during sessions for is intriguing. But the objection that has been reported as the label’s major one to releasing it at the time it was new – that its sound would have been a surprise to the band’s extant fan base – still holds water. Nothing in their discography matches it, and if you were just presented with the records and had no contextual data available, placing that song into a sequence that shows a logical progression – of writing, performance or production – would probably prove impossible: certainly, if you had no other information to go on, you would probably place it after Meat Is Murder rather than before in the band’s chronology. Nevertheless, some of its sonic elements are echoed in the album made shortly afterwards, most notably the use of harmonics and sustained tones in Marr’s guitar parts. To these ears, those bits of ‘How Soon Is Now’ have always sounded like or evoked birds – the slide-guitar parts as avian calls while the sonic imagery seems to suggest flight. But maybe that’s just me.

Perhaps oddly, considering the album title and the way it helped usher in an age where vegetarianism and animal rights moved from the fringes to the mainstream of western society (seriously: you couldn’t get a veggie burger or a meat-free lasagne in a British cafe in 1984, and if you asked for a meal without meat you’d often have been laughed at), there’s no other song on the record that broaches those subjects. If there is a predominant lyrical concern, it’s violence and abuse – of teachers against pupils in ‘The Headmaster Ritual’, of parents against children in ‘Barbarism Begins At Home’. Yet in a way these ideas are all of a piece, the words chosen with deliberation and precision: "barbarism", "murder" – these evils have become banal or mundane, and by using words to describe them which remind the listener of the horror the writer wishes to highlight, we’re forced to confront an atrocity we take for granted because of its ubiquity and reassess our responses to it. In truth, therefore, the album’s key unifying theme is not vegetarianism, or bullying, but social conditioning and double standards. It’s a record that reminds you that you have to draw your own lines, because the places where others have tended to draw them for us are built on a foundation of hypocrisies.

There are two songs that are, if not actual jokes, then pretty knowing sets of musical nods and winks – and a third song where a pastiche tumbles from being reverential to (presumably) intentionally amusing. The latter – ‘Rusholme Ruffians’, a tale of violence, danger and temptation in the temporary mini-Vegases that still descend for a few days on umpteen recreation grounds and car parks across the country – is as much in debt to the kitchen-sink dramas Morrissey mined for Smiths record-sleeve imagery as it is to the bequiffed rockabilly of Elvis Presley that the tune relies on. It’s clever and appealing, and you don’t ever feel quite sure about it – just like the people and the situations it describes and evokes.

Humour is never far away, even though this lot are supposed to be the masters of misery. In this one strange way (sorry), The Smiths are a bit like NWA: there’s quite a few laughs in the records, but significant parts of the audience seem predisposed not to find them. Morrissey is a hugely funny writer, as anyone who’s enjoyed his uproarious autobiography would have noticed without fail – yet too often his lyrics are taken at face value. This is nonsensical: we don’t presume him to be stumbling and inarticulate because the characters in his songs may be, yet many of us seem to assume that when he writes a couplet like "I want to drop my trousers to the world/I am a man of means – of slender means" that he’s bemoaning his lot rather than sending himself up for supposedly doing just that. There is also humour in the music. You can read Marr’s fascination with the "wrong" chords – such as how, in ‘The Headmaster Ritual’, he deliberately goes to a chord you’re not expecting next – or his apparent need to find new hoops for rock to jump through as devices intended not just to provoke and sustain attention but to raise a smile. What’s so consistently great about Meat Is Murder is that on more or less every track, it manages to do all of this, all at once.

‘Barbarism Begins At Home’, occasionally described as an attempt at funk, is fairly obviously not The Smiths putting in an application for a support tour with Level 42. Rather, between the lyric and Rourke’s bass line – a pastiche of the slap-and-pop style, more Kajagoogoo than Brothers Johnson – it is surely designed to evoke that atmosphere in an unhappy home where even the soundtrack is selected by others, where the individual and the different is crushed beneath the tyranny of supposed consensus. It’s difficult now to recall the era with quite the precision that may be required, and even harder to explain to anyone who’s come of age in our present epoch of digital superfluity – but music that the likes of The Smiths made was still very much considered to be the preserve of the outsider. They were among the most popular artists not connected to the major-label system, but their music was tolerated within the mainstream and never as big in commercial terms as their reputation today might make you think was the case. None of their singles got higher than Number 10 during the band’s lifetime: daytime radio play was limited, and even the evening-show plays they got became, eventually, a bit more begrudging, as they gained in popularity and DJs keen to champion new music perhaps felt the band were too big to need their help any more. Yet they were always more John Peel than Gary Davis, and so to hear this band – the heroes of the night – playing something that sounded like a slightly menacing, deeply unsettling take on the music daytime radio loved… well, you knew this couldn’t be an attempt at selling out – it was all about subverting.

The other clever musical joke comes in the form of ‘What She Said’, which Peel trailed on his show as The Smiths essaying heavy metal. It isn’t, quite, though you can sort of understand why he suggested it. Instead, what Marr did was to take the kind of double-time, triplet-based riff you’d occasionally find rock bands using for closing codas of songs, and constructed the entire piece out of it. The biggest wonder of all is that Morrissey managed to write and sing a song that could sit on top of it – it’s the lyrical equivalent of a winning ride on a bucking bronco. It’s ridiculous and brilliant at the same time – you’re laughing at how over-the-top it is while shaking your head in amazement at its daring. Marr even manages to finish the song in the "wrong" place – holding back the last crunching powerchord that would resolve the riff in a formally correct way (partially because the next chord in the sequence would send it all back to the top – for its duration, the riff seems to keep tumbling over itself, always ending back at the beginning in the musical equivalent of an Escher spiral staircase). It’s a short song and it’s showy, and it may be a bit too clever for its own good – but in its own way it’s a perfect encapsulation of what this band were about, and as fine if extreme an example of what they were capable of as can be imagined.

It’s also one of three songs on the album where Morrissey relies on ad libs apparently derived from folk song styles and traditions which take the place of hooks or choruses. It’s a curious habit and one he didn’t pursue for long. ‘Shakespeare’s Sister’, the non-LP single released just after Meat Is Murder and recorded around the same time, has a section in the middle where he gets close to it, but – unless a short blurt in ‘There Is A Light That Never Goes Out’ counts – the technique seems to be limited to this particular period. It happens in ‘The Headmaster Ritual’, where the hook is a wordless series of vocal sounds; in ‘Rusholme Ruffians’, as a kind of distant echoed response to the narrator’s rhetorical question about what would happen if "I jumped from the top of the parachutes"; and in ‘What She Said’, where it ends several of the stanzas. Why he chose to do this, and to do it such a lot but for such a brief period, isn’t clear, though it’s tempting to see it as both an attempt – possibly subconscious, though from someone so deeply committed to an ongoing investigation of what being British might mean, that seems unlikely – to imbue the Smiths’ material with something that tied it stylistically to a deep and ancient tradition of British songcraft, and at the same time as a nod to Pentangle, a key influence on Marr.

Another thing that strikes you ever more forcibly after 35 years is how describing Morrissey as a "vocalist" is woefully inaccurate. It was the preferred term of the era, particularly if audiences were weaned on punk and still in thrall, albeit at some remove, to the idea that technical proficiency was the enemy of musical creativity and a barrier to the communication of absolute artistic truth. But Morrissey was – and still is – a singer. More so than all but a handful of his contemporaries, the man knew (still knows) how to use that remarkable instrument to deliver a tune, inhabit a character and tell a story. In the years since, most of the focus of the considerable acclaim won by his songs (both with Marr and after the band split) has been on the writing, but his performances of them are just as important.

The curious approach to marketing the album reached a bewildering peak in the summer of ’85 when what one can consider the third single in the campaign was released. After ‘How Soon Is Now’ and ‘Shakespeare’s Sister’, the decision to release ‘That Joke Isn’t Funny Anymore’ bordered on the obtuse. Other bands had done OK without having singles taken from albums, some of them even on Rough Trade (The Fall spring most readily to mind), so it wasn’t as if releasing a string of non-LP singles would have been unprecedented. The song had to be edited for release as a single – the false ending on the album became the real ending of the 45, lest any radio DJ be taken unawares and start to talk in the gap – and, with the definite exception of the title track and the possible exception of the beautiful, rain-spattered ‘Well I Wonder’, it’s easily the least immediate song on the record. That said, it remains a quintessential Smiths song, a bruised and beautiful thing aching with melancholy and simmering with the sense of explosive power held in reserve. A better bet, surely, would have been the other track on the album which distilled the essence of the band into a single song – ‘I Want The One I Can’t Have’ teeters similarly close to self-parody but is far more immediate, its up-tempo brashness probably better suited to the demands of mid-’80s daytime radio and more likely to tempt the curious uncommitted into a purchase.

The lesson is clear. This wasn’t a record that improves by being broken down into singles, parcelled up into hit-worthy packages, taken apart to be put back together later. In truth, any of these songs could have been singles, but perhaps it would have been better if none of them ever were. Gallagher is right: it is the band’s best album. The Queen Is Dead tends to take the plaudits, and Morrissey reckons the fourth and final studio LP, Strangeways, Here We Come, found the group firing on every cylinder and is, to his mind, their finest achievement. But the life-changing Meat Is Murder is the one.