For those of us growing up in suburban towns, reared on pop radio and too young to have been effected by punk’s brief seismic flash, The Police were one of the key singles bands of the late 1970s and early 1980s. It didn’t matter to us that the trio had hitched its wagon to punk’s spiky aesthetic or that guitarist Andy Summers was actually older than some of our parents. Nor did it matter that Sting had worked as a primary school teacher whilst noodling away in various jazz combos in his spare time or that drummer Stewart Copeland’s father had been a CIA operative involved in covert foreign policy operations. What mattered to us, at that age were the possibilities at the dawn of teenage years, fueled by endless energy and the pursuit of fun. The grooves contained on those 7” singles possessed the power to make us dance, sing and form friendships that would last a lifetime.

I can still recall the balmy summer of 1979 when, as a boy scout, building an improvised bivouac shelter made from branches and fern leaves with friends in a forest in Wales, a small transistor radio kept us company with the sounds of the season. The Ruts’ ‘Babylon’s Burning’, Boomtown Rats’ ‘I Don’t Like Mondays’, The Darts’ cover of ‘Duke Of Earl’ and The Police’s ‘So Lonely’ – with the chorus that always prompted the chant of "Sue Lawley" – were the songs that we all agreed on and sang to as our makeshift home was being constructed under gloriously cloudless skies. Similarly, the memory of rushing to Harlequin Records in Slough’s Queensmere shopping centre to buy The Police’s ‘Message In A Bottle’ on green vinyl is indelibly etched on the brain as the record hurtled up to the top of the singles chart.

With the advent of post-punk, new pop, the nascent hip-hop scene and any number of bands bringing electronic music into the charts and mainstream consciousness, the first few years of the decade that came to be defined by strife, civil unrest and unfettered deregulation proved to be some of the most exciting times in music since the pop explosion of the 1960s. This wasn’t a time to look back; everything that we needed from music was rooted in the here and now. In retrospect this was also a time of teenage exuberance, that period of time where the world revolves around the idealism and anxieties of youth but what was true was that the best music of the day was intent on moving things forward.

By 1983, The Police were one of, if not the biggest band on the planet. With the exception of their debut, Outlandos d’Amour, all of their albums – Regatta De Blanc, Zenyatta Mondatta and Ghost In The Machine had reached pole position in the album charts on the back of singles that frequently ram-raided radio playlists, the top 20 and any of the teenage parties that were thrown when the parents went away for the weekend. But as music kept pushing onwards – this was the year that saw game-changing releases from New Order in the form of ‘Blue Monday’ and Frankie Goes To Hollywood’s ‘Relax’ – The Police, whilst keeping their eyes firmly fixed on the stadiums that would house them until their eventual demise, were more interested in creating a package that used production as an end itself rather than a means.

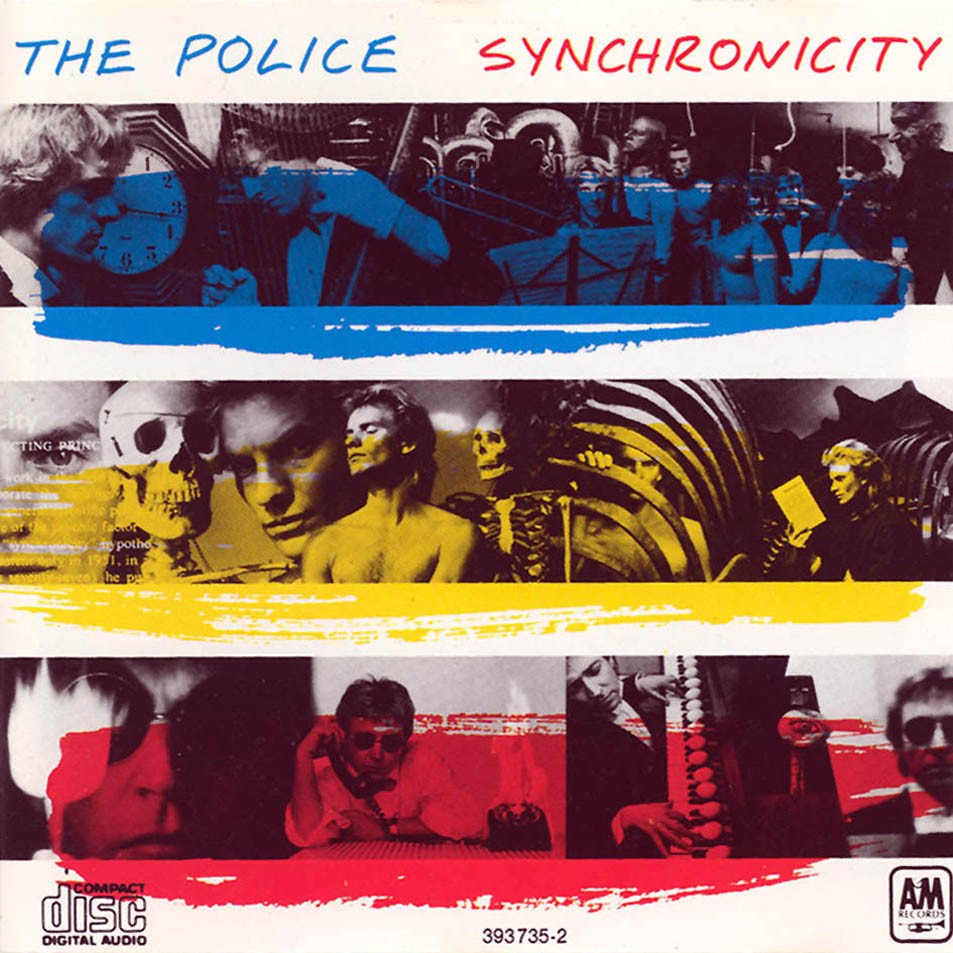

In common with many of the big names of the time and, as if anticipating the oncoming digital revolution on the form of the compact disc and setting its sights firmly on middle America, Synchroncity is an album that smooths away the rough edges and, in turn, the joy that beat at the heart of their earlier releases. Produced by Hugh Padgham, the man credited with creating the gated drum sound that would come to dominate and horribly date the sound of so many of the 1980s’ pop and rock releases, The Police’s fifth and final album was a triumph of style over substance that seemed to predict the horror of Yes’ 90125 that dropped like an unwelcome fart later in the year.

And yet, whilst employing all the technological advances that 1982/3 had to offer, Synchronicity is an album that harks back to the age of prog rock, where musical chops were often valued more highly than anything resembling passion or soul. Moreover, Synchronicity puffs itself up to deal with Big Themes. Not that this was new territory for The Police. Previous releases from the band had dealt with loneliness, surburban ennui, relationship breakdowns and Northern Ireland among others but here The Police were embracing Jungian concepts, the ecology, the Cold War and other global concerns. The problem is that, in the main, they fail to convince mainly because they don’t sound too convinced about these issues themselves.

Recorded in 1982 in the idyllic setting of Air Studios in Montserrat, Synchroncity was constructed under a great deal of strain as the personal and professional relationships between Sting, Stewart Copeland and Andy Summers began to unravel like so much bad stitching. These circumstances are stamped over the recording process and final product. With Copeland ensconced behind his drum kit in one studio, Summers in another and Sting marshalling proceedings in the control room, the separation sought by Padgham is clearly reflected by playing that is smooth, clinical and ultimately lacking soul. This is less a team effort and more a patchwork sown together and buffed to a gleaming and cold surface sheen that points the way to the muso wank of Sting’s first solo album, The Dream Of Blue Turtles.

Opening with ‘Synchronicity I’, the album’s stamp of virtuosity is evident with a sequenced riff that gives way to Sting’s steady bass and Copeland’s metronomic time keeping. Summers is barely in evidence throughout save for a number of punctuating chords. What was started on the preceding album, 1981’s Ghost In The Machine, is here brought to unholy fruition courtesy of a production aimed at hitting the widest possible audience with the minimum amount of dirt and grit. Factor in Sting’s simplistic view of Carl Jung’s concept of synchroncity – “A star fall, a phone call/ It joins all” and it becomes apparent that the broad brush strokes applied here are going to be a running theme.

And so it becomes with the eco-themed ‘Walking In Your Footsteps’ wherein Sting’s extra-curricular activities throughout the 80s begin to manifest themselves. Comparing the plight of the dinosaurs with that of the human race in the closing overs on the 20th Century, the song contains one of his most toe-curling couplets as he muses, "Hey mighty Brontosaurus/ Don’t you have a lesson for us?" To which the only answer can be, “Not really mate. The dinosaurs were wiped out by a bloody great asteroid smashing into the earth which doesn’t really compare to the human race hoisting itself by its own petard."

It’s difficult to shake the feeling that Andy Summers’ repellent and hateful ‘Mother’ appears on the album for no other reason than to grab some songwriting royalties in order to fund his next project with Robert Fripp. Over a horrendous dirge in 7/4 time, Summer’s supposed Freudien howl comes across less as anguish and more as out-and-out misogyny. "The telephone is ringing/ Is that my mother on the phone?" he shrieks be before imploring, "Won’t she leave me alone?" But the real kiss-off arrives when he decides that, "Every girl I go out with becomes my mother in the end", which makes him sound like someone only too happy to sit in his own shit rather than man up and face up to adult responsibilities.

Equally dire, though at least somewhat more tuneful is Stewart Copeland’s contribution of ‘Miss Gradenko’. Musically presaging Paul Simon’s Graceland or, like Malcolm McLaren’s ‘Soweto’, cocking an ear to what was happening in South Africa, this tale of cold war skulduggery feels like, a la Summer’s contribution, little more than an attempt to get a share of the publishing that had been serving Sting so well rather than any serious attempt to make sense of the fear of atomic war that constantly hung over that most paranoid of decades.

Synchronicity does of course contain one stone classic that appears in a four-song run that prevents the album sinking completely into a slough of disappointment. Though its ubiquity across weddings, mainstream radio and utter mangling at the hands of Puff Daddy (‘I’ll Be Missing You’ featuring Faith Evans) have served to dull its impact over the years, taken in the cold light of day ‘Every Breath You Take’ justified both the The Police’s position as the then biggest band in the world and Sting’s songwriting ability. Anchored by Andy Summer’s circular arpeggiated riff and Stewart Copeland’s measured and economic drumming, the sense of menace and dark obsession at its very heart is palpable throughout. Though born out of love, this is what happens when that strongest of human emotions turns on a coin to become its polar opposite. What once brought two people together has torn them apart and through the eyes of Sting’s protagonist – "Since you’ve gone I been lost without a trace/ I dream at night I can only see your face/ I look around but it’s you I can’t embrace" – we see the result of one half still clinging on to a past that can never be repeated again. Though any sympathy that we have for him is soon dissipated thanks to verses that articulate a stalker’s obsession that could very likely turn to revenge and an ever-decreasing spiral of more hurt and pain, this is a fine articulation of relationship’s breakdown and its painful aftermath.

The song was subsequently given a second, and arguably more powerful, lease of life when Sting re-wrote the lyrics and contributed a new version to the series finale of satirical comedy Spitting Image. Over a picture of a setting sun, a montage of Ronald Reagan, Margaret Thatcher, P.W.Botha, Ayatollah Khomenei and other political leaders whose contributions led to the unnecessary suffering of millions, Sting intones, “Every wall you build/ Every one you kill/ Every grave you fill/ all the blood you spill/ I’ll be watching you… on that judgment day/ there’ll be a price to pay/ And I’ll be watching you.” It’s almost enough to make up for the misery that his subsequent solo career has inflicted on lives ever since.

‘King Of Pain’ finds Sting once again returning to theme of global injustice and suffering. This isn’t a solipsistic moan at the emptiness of the millionaire rock star lifestyle but a resigned sigh in the face of a world seemingly unwilling or unable to change the course of a ship heading for the rocks. Similarly, ‘Wrapped Around Your Finger’, uses Homerian imagery to envisage a time when the tables turn and the roles of master and servant are finally reversed. Both tracks are characterised by Stewart Copeland’s uncharacteristically restrained playing and Summers’ declamatory guitar that weaves itself in an out of the verses to create a sense of light and shade without dominating the song.

Preceding ‘Every Breath You Take’, ‘King Of Pain’ and ‘Wrapped Around Your Finger’ is perhap’s the album’s highlight in the shape of ‘Synchronicity II’. Much like a Hollywood take on a Ken Loach film, this is a global, widescreen version of The Jam’s ‘Town Called Malice’. Once again, the grind of daily suburban existence, monotonous in its repetition as painful struggles are made to make ends meet whilst trying to make some sense of a life that seemingly has no other purpose than to reproduce whilst making others rich from your labours. Summers, for so long playing a largely muted role throughout the album, truly comes into his own here, his pushing and pulling adding drama to the sense of frustration and restrained seething that pumps in its heart of darkness.

The Police’s least satisfying work, Synchronicity went platinum eight times in the United States where it occupied the Number 1 slot in the Billboard Hot 100 for a staggering 17 weeks. Their colossal status in America found the band headlining Shea Stadium in an evocation of The Beatles but it wasn’t to last. Internecine squabbling which saw Copeland writing "Fuck off you cunt" across his drum heads to articulate his feelings to his singer, each beat being a metaphorical punch, and, despite an attempt to write a follow-up album, The Police quietly drew a veil over their career after one final concert in New Jersey’s Giant’s Stadium in 1986.

If anything, Synchronicity does prove one point conclusively and that’s that The Police were, first and foremost, a damn good singles band. With each album becoming more reliant on filler and sub-par material, the singles always remained the perfect sound to fill the airwaves among the shocking dross that were the staples of daytime radio in that bygone age. So good, in fact, that they still possess the charm and power to return me to an infinitely more innocent age and place. And that ain’t bad.