Busy Bee liquor store, El Paso. A young man walks in from the rainy evening and orders a bottle of whiskey. The proprietor, Delta Richard Pinney, goes to retrieve it from the shelf. When he turns back, there’s a .38 Special pointed at him. “Give me all the green money” the stick-up man orders, as he has a dozen times before, all over the country. But this evening his luck has run out. The man holding the revolver goes by the name of Alvin Krolik. He was once a judo instructor in the Marine Corps, with ambitions to be an artist, but he’s divorced and washed up now. After committing a spate of armed robberies, he’d turned himself in, determined to change his life. The judge gave him a second chance and he was packed off to paint murals in a monastery. He fell back into his old ways, so here he was.

Krolik doesn’t know the liquor store owner or the fact he’s a former police officer. Or that he’s already killed two would-be robbers and wounded eight others. Noone has ever robbed the place and walked out intact. There are eight Smith & Wesson pistols and a shotgun, strategically placed, always within arm’s reach. When Krolik reaches for the banknotes, he takes his gun and his focus off the shopkeeper just for a second, but it’s time enough for Pinney to draw and put four bullets into the artist. He leans over the counter with a second revolver and finishes him off with another five.

The story runs as a cautionary tale in local and national papers and comes to the attention of two songwriters, Tommy Durden and Mae Boren Axton, the latter of whom had introduced a teenage Elvis Presley to ‘Colonel’ Tom Parker. Axton was struck by one wrinkle in the tale, a single line from a memoir Krolik had been writing: “This is the story of a person who walked a lonely street.” She started to wonder what that street would look like, and where such a damned soul might reside. And there it was, ‘Heartbreak Hotel’, with its neon light blinking in the night rain.

It seems strange to frame John Cale as a figure, perhaps the figure in modern music, who walked a lonely street. For one thing, he’s the most prolific and influential of collaborators. He produced The Marble Index, The Stooges, Horses, The Modern Lovers, and numerous others. He appears on Bryter Layter, Chelsea Girl and Another Green World. At one stage, his backing band were members of Little Feat, at another time Roxy Music. There he is with John Cage at the 18-hour performance of Satie’s Vexations, at La Monte Young’s Theatre of Eternal Music, at Warhol’s Factory and Exploding Plastic Inevitable, at CBGBs and the Ocean Club alongside Patti Smith, Lou Reed and David Byrne. Yet he always seems a singular figure even in group photographs. The eye of the storm. Not aloof or stern but apart. Outside of the outside. Even in the Velvets, he looks different. His image belonging to an earlier age, beatnik or Baroque even. Less a denizen of New York’s underground and more an undercover Jesuit come to cleanse them.

There’s a sense with Cale of always moving, never settling or fitting. There he was with death-drones at the time of flower power. Playing chamber pop at the time of glam. He helps invent punk and then abandons it at birth. There are those who set out to be contrary, and the results are almost always cringeworthy, reactionary. And there are those who are just different. Cale was not a creature of NYC or even London. He came from a Welsh mining town in the valleys. The Celtic periphery has always been a rich source of weirdness, as Cale acknowledged in his book What’s Welsh for Zen: “This was a strange, remote, some said mystical land. It was rich in the Arthurian legends and had retained its identity through centuries. It was one of the few parts of Britain that neither the Romans nor the Normans conquered. Our part of Wales was cut off from the body of the country by natural defensive barriers of rivers and mountains. When the Romans came, we waited for them out in the hills. When the English came, we withdrew deeper into the caves. During the reign of Henry IV, Owen Glendower became a lifelong scourge from the stronghold of the mountains. Through these wars, one can chart the growth of the Welsh nation. Our language, our literature and our music gave us a cherished sense of nationhood.”

Even there, Cale’s path was relatively solitary. Brought up partly by his Welsh-speaking grandmother who forbade English, he couldn’t talk with his English-speaking father until he was seven. He was a sickly child, medicated with opiates, which would reverberate throughout his life. His was, in his own words, a ‘draconian’ religious upbringing with his one escape being his precocious talent for music, though even this was horrifically marred by sexual predators, at a time when speaking about sexual abuse was utterly taboo. Classically trained, Cale’s path changed dramatically due to a mistake. Due to perform a self-composed score on the radio, his notation was left behind, so he had to improvise, which was a revelation and led to him escaping the strictures and weight of the past. And escape them he did, bringing the rest of us with him. You can hear the results in the crazed bacchanalian viola that ignites ‘Venus In Furs’ and you can hear what the Velvets lost in the difference between White Light/White Heat and their sublime but sedate self-titled album, released after Cale’s departure from the group: they had lost their agent of chaos.

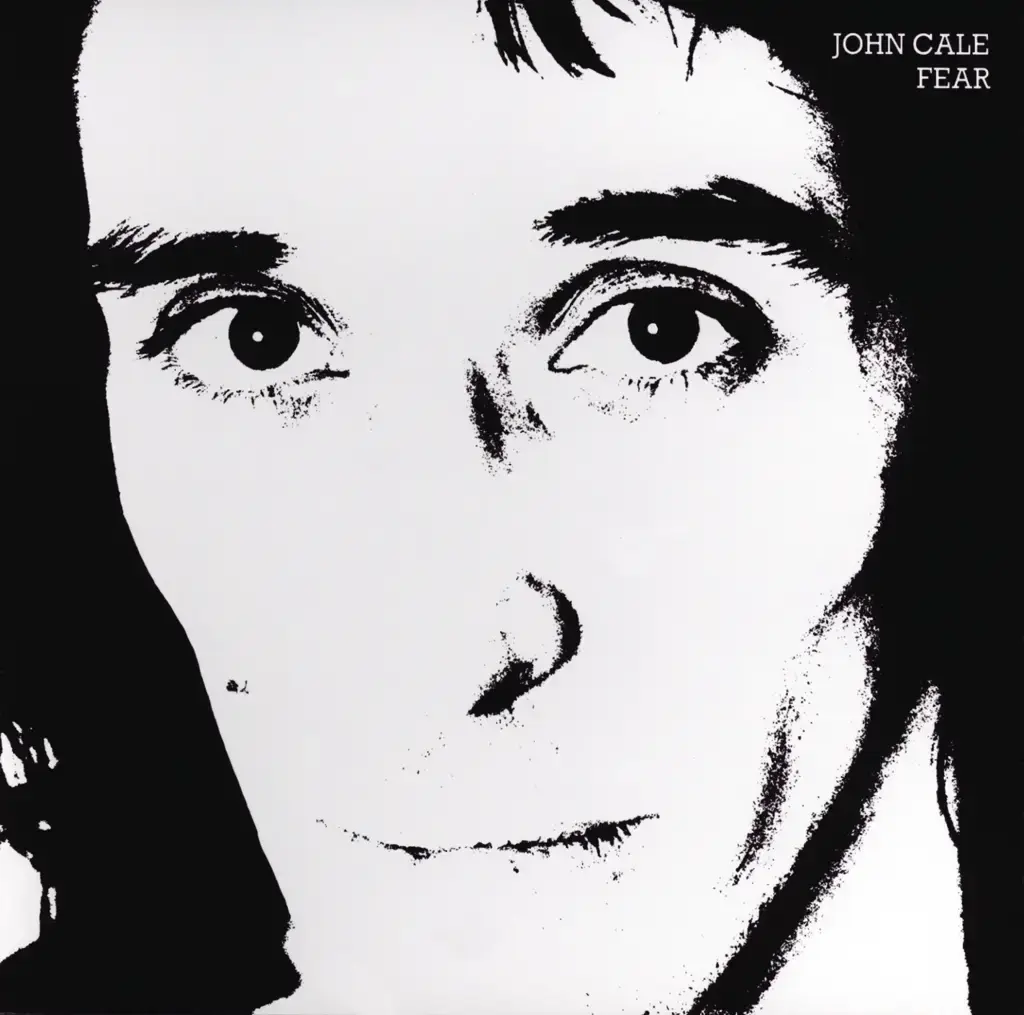

Few would have expected then the European elegance, barely of the same century, of his early batch of solo albums, culminating in Paris 1919. Yet the wild troubles of the past had never entirely dissipated, and they began to gather again. Paris 1919 had, after all, ended with the words, “The anaesthetic wearing off / Antarctica starts here”. And it was themed around the peace treaty that ended one world war and helped to start another twenty years later. Cale’s marriage had disintegrated, and with drink and drugs ever-present, he crash-landed back in Blighty. And so, begins his trilogy of records with Island, a unique chapter in his career, as the first album, Fear, sets out from the beginning with its stark exposed cover portrait. ‘Fear Is A Man’s Best Friend’ is a spirited opener. One of Cale’s calling cards is his combination of opposites. You can see this on the Velvet’s ‘Sunday Morning’ where Cale’s celesta opening is so delightful you might easily miss the deep paranoia of the lyrics (there’s a nod to the Velvets’ ‘I’m Waiting For Fhe Man’ in this album’s first line). Fear’s title track has a similar paradoxical approach. The regal prettiness of the verses and the bouncy chorus jar in a beautifully abrupt way with lyrics that are savagely fatalistic, “Life and death are just things you do when you’re bored […] Home is living like a man on the run / Trails leading nowhere, where to, my son? / We’re already dead, just not yet in the ground.” It vies between threat and self-ridicule, “When I’m on the prowl, you better run like hell”. As if to balance or undermine the catchiness of the song, or simply no longer stemming the tide of emotions in his life at that moment, the song collapses into screams and noise. Aside from his confrontational live shows at the time, you get a sense here why the punks-to-come looked up to Cale, even though there’s no punk cliches here musically. He’s genuinely idiosyncratic, mercurial, and enjoys fucking with expectations, with the listener and himself. Unlike most artists of the time (this era was prog rock’s plateau), he’s telling it like it is, in a raw sense and without dishonesty.

Another of Cale’s talents is the ability to compose an incredibly moving ballad, melodically, which he then proceeds to mess with via absurdism or sarcastic wit. His lyrics are wordy and puzzling one minute (it’s worth remembering English is his second language and one he frequently experiments with) and visceral the next. In ‘Emily’, a heartbreaking nautical lilt is coupled with the sounds of a sea of schmaltz washing bodies onto a beach, stepped over by the starry-eyed lovers, now departed. Unusually, by contrast, ‘Buffalo Ballet’ is played straight, a Midwest spiritual following the decline of a Kansas town when the cattle and gold gradually fade away. Significantly, the town’s name Abilene comes from the biblical ‘city of the plains’, a distant cousin of Sodom and Gomorrah. The shadow of the church is never far from Cale’s sorrowful hymnals (“the strongest influence on us was our preachers” he wrote “They were not dry, ascetic scholars, but bold men who dominated their flocks with the fear of the wrath of the Lord”), just as sin is never far from his livelier work.

There is laughter to be heard in the ruins, just as Cale’s tales of self-ruin are full of self-deprecation. ‘Barracuda’, for instance, is full of the playful/sadomasochistic mischief that can be found on Brian Eno’s warped pop albums of the period (Eno, and his Roxy cohort Phil Manzanera, appear throughout the record). Rather than a series of confessionals on a disintegrating life, Cale articulates the feelings through strange distant little vignettes, “Ten morons with their whistles blowing / Howling like a winter gale” that call to mind, in their austere oddness, his fellow countryman the poet R.S. Thomas. When Cale sings “the ocean will have us all”, he makes it sound like a relief. At one stage even the music seems to be cackling in the background. The twinkly ‘Ship Of Fools’ is like an atrocity in a snow globe, “The black book, a grappling hook / A hangman’s noose on a burnt-out tree”. The most poignant moment on the album is when you realise that he’s sailing the whole time back to the landscape of his childhood in Carmarthenshire.

One of the more surprising tracks is ‘Gun’, which has some of the feel of an early Velvets proto-punk stomp but also seems to anticipate grunge with its head-down Crazy Horse fuzz (there are some outstanding moments when you can hear the guitars getting the Eno sonic raygun treatment, turning it briefly into a space-age type of grunge). ‘You Know More Than I Know’ similarly has a bridge feel between solo John Lennon and the more melodic wonders of a band like say Fugazi (think ‘I’m So Tired’). By contrast, his duet with Judy Nylon ‘The Man Who Couldn’t Afford To Orgy’ harks back to the doo-wop/barbershop quartet age. Its lovingly kitsch and hilarious, again because he plays the straight guy to the deviancy of his music. And his pronunciation of ‘orgy’ will never be unfunny. For all his supposed pretension (there’s a scene in Neneh Cherry’s recent memoir A Thousand Threads where she overhears someone in CBGB claim that Cale, suddenly vanished from the stage, is “downstairs somewhere, probably OD-ing on his ego”) Cale’s solo work is among the most fascinating prolonged self-deflations of music celebrity mythology. So complete is it that it simply establishes him in another realm, a forefather of brilliant obstinate misfits (hence his collaborations on 2023’s Mercy with heirs like Laurel Halo, Dev Hynes, Fat White Family and so on). Aided by another uncategorisable artist, Richard Thompson, the album finishes with ‘Momamma Scuba’, a glimpse into Cale’s next more groove-based and abrasive album.

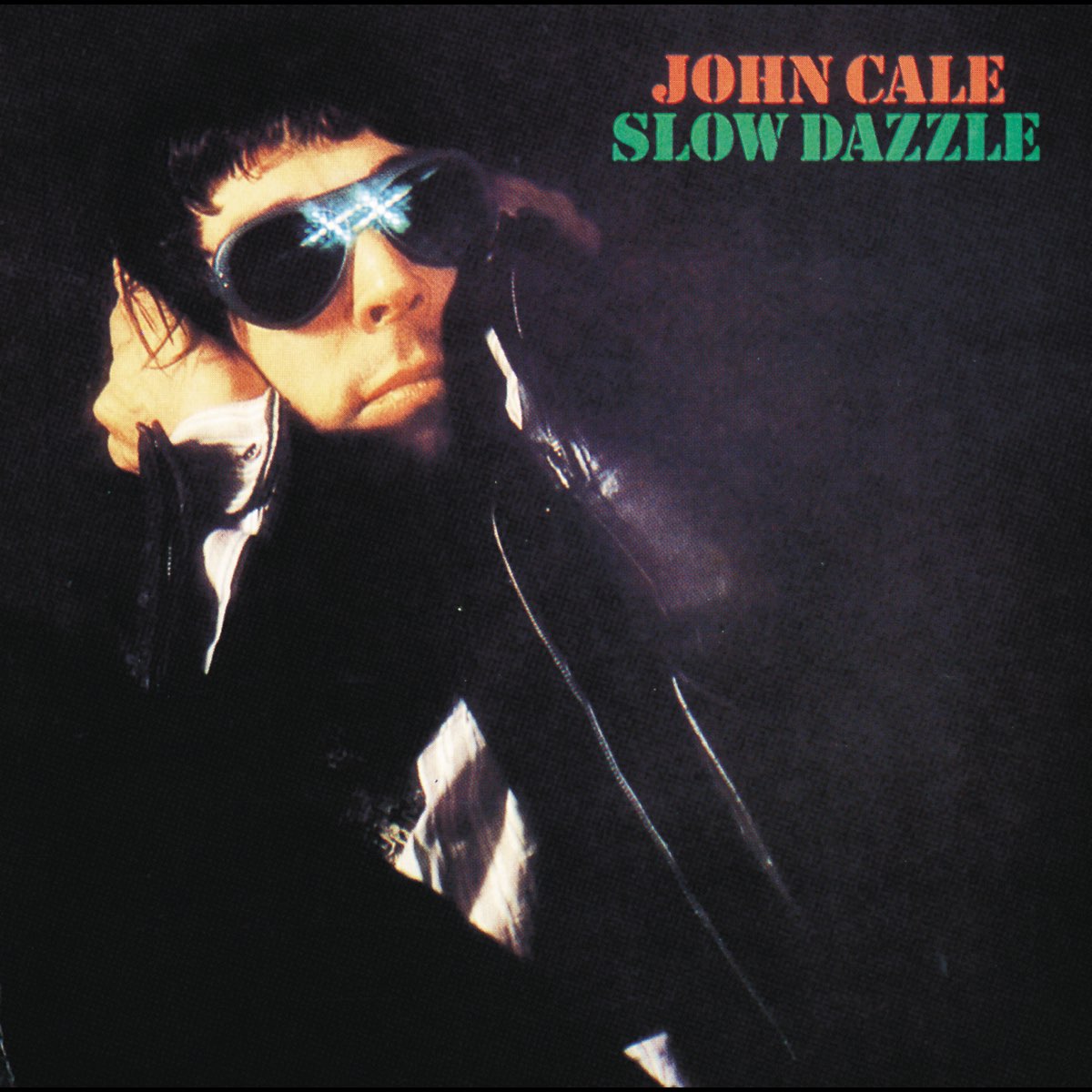

By the time of Slow Dazzle, Cale is so firmly established in Heartbreak Hotel that he has taken to refurbishing the place. His cover version of the song is an impressive centrepiece to the album and the trilogy itself. It’s a brilliant rewriting, so transformative that after a while, you forget it’s a cover at all. Occasionally, you’ll see the song listed as among the most disturbing ever and while it has something of Psycho or The Shining to it in its histrionics, next to a song like ‘Hamburger Lady’ or ‘22 Going On 23’, it’s Hammer Horror ghost train music. You half expect Vincent Price, or the ghost of Meatloaf, to pop up at any moment. More discomforting is how Cale ended up residing in Heartbreak Hotel, a condition this song was partly responsible for. It was played at the June 1, 1974 Rainbow Theatre concert where Cale performed with Nico, Eno and Kevin Ayers, the latter the handsome frazzled psychedelic guitarist, formerly of Soft Machine. A live album was released with a contender for the most uncomfortable record sleeve; a photograph taken by Mick Rock of the foursome. Ayers is coyly smirking while Cale looks close to murdering him. Given that Cale had interrupted Ayers and Cale’s wife of the time screwing the night before the concert, it’s likely murder may well have been on his mind. How they got through the show is unfathomable.

The experience led to ‘Guts’, the most emotionally raw song of Cale’s career. The tune is early new wave, with even a touch of cock rock, but the subject is brutal and remarkable. It begins with the line “The bugger in the short sleeves fucked my wife…” and ends in a cacophony of inarticulate screaming. At times, it is dripping with sarcasm (“Back home, fresh as a daisy to Maisy, oh Maisy”) and others it spits venom. It seethes with disgust and loathing, inner and outer, and there’s a disturbing overlapping of sex and violence throughout. Yet it’s funny in the unlikely way that your life collapsing might somehow be funny from a certain angle. If Cale seems to have rapidly passed through the five stages of grief or simply realised the futility of it all (“And then you’ll notice / How the waster and the wasted / Get to look like one another / In the end, in the end”), there is no reconciliation to be found and it ends in anguish. It sounds like someone about to explode or already tearing himself apart. If it were a final song, you’d worry there would be no further albums or no more artist (in fact, Cale later reconciled and played with Ayers; all’s fair in love and war).

Due to ‘Heartbreak Hotel’ and ‘Guts’, Slow Dazzle has a reputation for being a kind of Slough Of Despond sort of album but it’s much more multifaceted and surprising than that. ‘Taking It All Away’ shows Cale’s immaculate and warped pop sensibilities, as does ‘Mr Wilson’ even if he sabotages the mood with forlorn laments and sours his Pet Sounds-esque xylophone tribute by confessing to Brian Wilson that he has “a monkey on his back”. Mornings-after recur, from the honky tonk blues of ‘Darling I Need You’ to ‘Dirty Ass Rock ‘N’ Roll’ which sounds like a barroom Bob Dylan nursing a bastard hangover. ‘I’m Not the Loving Kind’ shows Cale’s skill in subverting pop formulas with unexpected turns and by writing heartless songs of heartache. The weirdest moment on the album is the finale, ‘The Jeweller’. Initially reminiscent of the Lou Reed-written Cale-recited sardonic short story ‘The Gift’ (from White Light/White Heat), it’s a very different beast, a crawling bodyhorror tale that grows in intrigue and unease with every drone and word. It’s a stunning, troubling end.

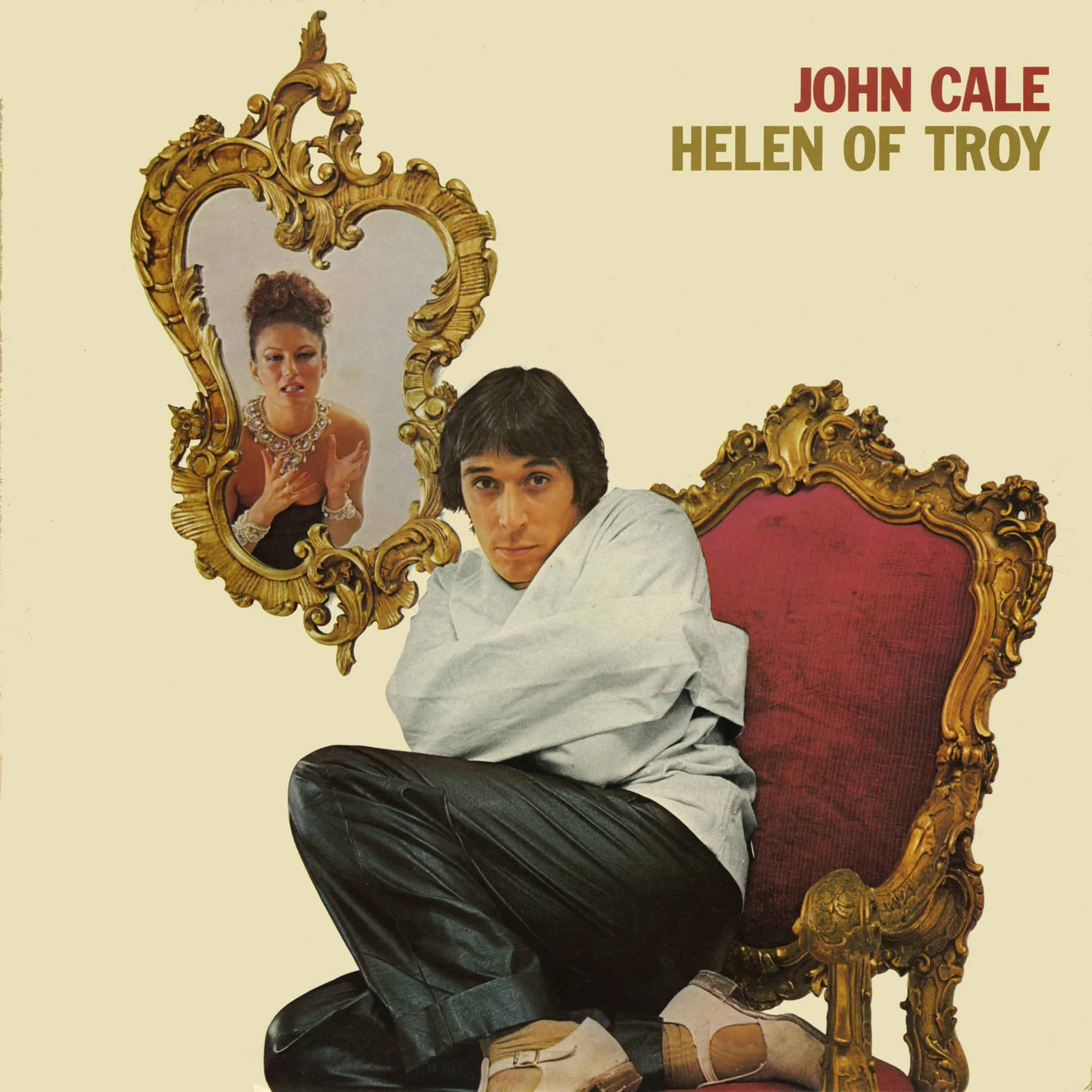

Still reeling from listening to ‘The Jeweller’, it’s not entirely a surprise to find that Cale is pictured wearing a straitjacket on the garish cover of Helen Of Troy. It was an ill-fated momentum-breaking album, cobbled together by the record company against Cale’s wishes, though he has been magnanimous about it since. For all its poor odds n’ sods reputation, however, it’s remarkably coherent. Most of the songs could have fitted on the previous two albums though Cale has expanded the sonic palette, adding choral touches to ‘My Maria’, triumphal brass to ‘Helen Of Troy’. The songs sound characteristically understated and overstated at the same time. The provocative title track hides a biting Dylanesque lament beneath the monologue of a lusty street-queen, a homoerotic version of ‘The Man Who Couldn’t Afford To Orgy’. There’s still a sense of Cale having first rate pop compositional skills and the same self-sabotage at play, the same sense that music and fame is vital and ludicrous. He’s still writing the most love-haunted songs while claiming his heart has turned to stone. Inspired by Johnny Cash’s ‘I Walk the Line’, ‘I Keep A Close Watch’ begins as romantic and lush as any Burt Bacharach song, echoing back to one of Cale’s career peaks ‘The Endless Plain Of Fortune’ from Paris 1919.

One of the most endearing and frustrating qualities Cale possesses is his restless impulsive nature. It’s striking how many sub-genres of music he casually predicts and how quickly he moves on to something else. On Helen Of Troy, he lingers a little longer than usual. There are several tracks (‘Save Us’, ‘Sudden Death’), that have a scuzzy damnation-gospel garage feel that strongly anticipates early Nick Cave And The Bad Seeds, while ‘Leaving It Up To You’ (one of the more deranged tracks, censored in later pressings) is so Talking Heads you could seamlessly slip it into Fear of Music several years later. Though he’d produced Jonathan Richman’s masterpiece The Modern Lovers in 1972, it had not yet been released, arriving perfectly in time for punk so Cale’s version of ‘Pablo Picasso’ was the first to be publicly heard on record. It’s a strong cover, turning the song into a sleazy slide blues with a Southern feel, but it loses some of the naive charm of the original (Richman was so far ahead of his time with his Gen X/Pavement-esque slacker style he even looks like a time traveller in photographs). The only signs of the album being thrown together by the record company is ‘Baby What You Want Me To Do’, a perfectly serviceable road blues, reminiscent of the latter stage of The Doors when Morrison had traded in his topless Adonis image to become a bearded barfly. Whether it would have made Cale’s final cut is debatable, and it’s tempting to imagine what the album would’ve looked and sounded like had he had the creative control he deserved.

Cale understandably left Island, after this remarkable year-long burst of creativity, or maybe they left him. Yet he didn’t exit Heartbreak Hotel. There was a long gap before his return with the post-punk Honi Soit and the exceptional Music For A New Society, which regardless of critical praise, Cale regards now as a miserable time. “People like watching suffering,” he concluded. Cale got out eventually and we should be glad of it, given he’s still making essential music in his 80s. Anyone can find themselves in Heartbreak Hotel, if they are not careful and even sometimes if they are. It’s a bad place to end up but, sadists as we are, what sweet, unhinged music can be heard coming out of its rooms and on the lonely streets that lead to it.

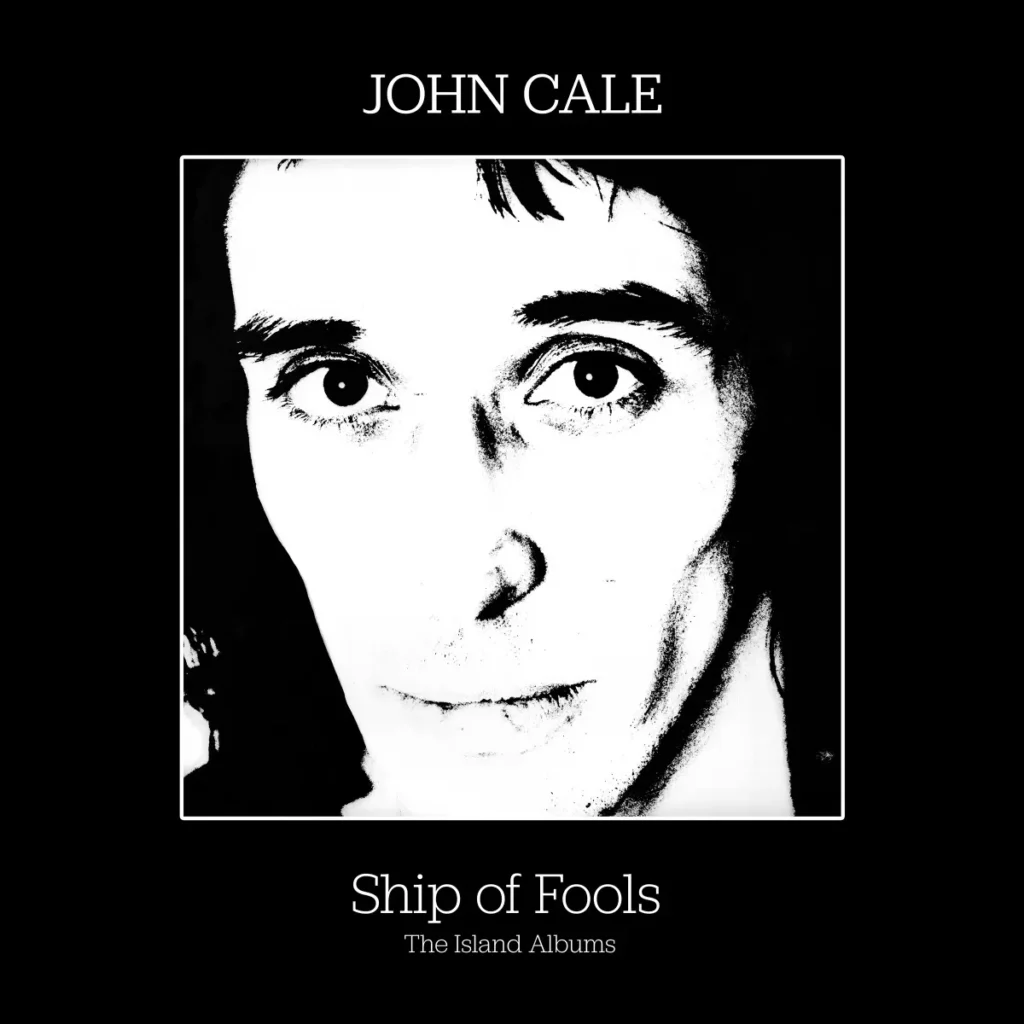

Ship Of Fools: The Island Albums, a new 3xCD boxset, is out now via Esoteric. 6 December will also see vinyl reissues of all three albums. You can pre-order Fear here, Slow Dazzle here, and Helen Of Troy here