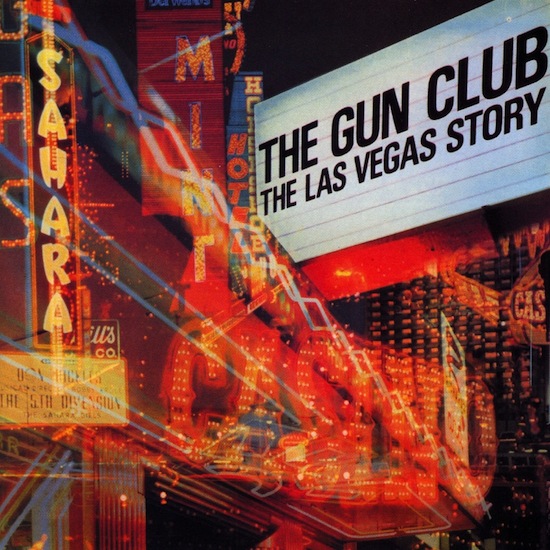

It’s been written that all farewells should be sudden but as is so often the case, a goodbye can be a long and drawn out process with many underlying factors painfully protracting the adieu. And so it went here. The Las Vegas Story, the third full-length album by The Gun Club, released 30 years ago this month, is, in a number of ways, a farewell of sorts. A farewell to the under-production of the band’s first two albums, The Fire Of Love and Miami; a farewell to an America that was rapidly changing under the auspices of Republican president Ronald Reagan and, though they didn’t know it at the time, a farewell to The Gun Club themselves who would disintegrate by the end of the year.

The origins of the album began with the departure of drummer Terry Graham on the eve of an Australian tour – though he would soon return – and the welcoming back to the fold of original guitarist Kid Congo Powers who’d been playing with The Cramps and making his presence keenly felt on the classic Psychedelic Jungle and Smell Of Female albums. With The Cramps mired in legal litigation with their label and wanting a change in direction – they would eventually swap the two-guitar line-up for the more conventional addition of bass guitar – and Powers eager to start playing again, the guitarist was asked to rejoin The Gun Club by the band’s leader, Jeffrey Lee Pierce. Augmenting the new-look line-up was the addition of bassist Patricia Morrison, formerly of LA punk band The Bags.

Though delving into the past for inspiration, The Gun Club were mindful that their new music should re-interpret what had gone before to create a new vernacular. With Pierce picking up the guitar, the band allowed for an introduction in interactivity between guitars that had previously been in little evidence. Powers, for his part, brought with him the lessons learned from The Cramps as well as a distortion pedal that, coupled with his open E tuning and increased musical skills, gave the band a wide screen sound and meatiness that had previously eluded them.

From the off it’s evident that this a very different incarnation of The Gun Club. The opening mini title track, itself characterised by bizarre sounds that were accidentally conjured up the studio, gives way to Terry Graham’s methodical and tribal drumming which in turn usher in a gale of feedback and Power’s coruscating guitar at the start of the menacing ‘Walking With The Beast’. At once there’s drama and menace and a clear line drawn in the sand from all that the band had done before. All the promises that had been previously made are here delivered and then some. A high watermark, this is a lean and muscular band and one making good on its intentions.

This reinterpretation of the past is apparent throughout The Las Vegas Story. Check the rockabilly rhythms of ‘My Dreams’ with its snapping snare and rollicking bass, the weeping slide guitar and Jeffrey Lee Pierce’s impassioned and imploring singing. The component parts may be recognisable but the whole is something new altogether. Similarly, the devastating ‘Stranger In Our Town’ is powered by one of the band’s – and, indeed, rock & roll’s – filthiest riffs before exploding into an anguished howl that continues to haunt well after the fact.

Elsewhere, The Gun Club look to The Pharaoh Sanders Quartet for their part cover of ‘The Creator Has A Master Plan’ which gives itself up to George Gershwin’s ‘My Man’s Gone Now’. Like The Stooges and The Velvet Underground before them, The Gun Club sought not to replicate jazz but to use it as a springboard within the rock idiom. The results are weirdly beguiling, as the former takes the opening section of the original piece to create something quite unsettling while the latter could easily be the afterhours soundtrack of Satan’s own cocktail bar, a watering hole for the damned and misbegotten souls forced to forever live their sorrows and sins with no hope of redemption. Pierce’s moaning and wailing convincingly convey the pain of loss and loneliness, a solitary howl set against a universe that refuses to heal his hurt.

Lyrically, The Las Vegas Story is tinged with sadness, loneliness and a farewell to a world that’s changing and not for the better. With the old consensus being set up for a brutal stripping and dismantling in favour of something uncaring and psychotic – the ramifications of which we’re truly feeling now, – The Gun Club subconsciously capture the mood of the times and none more so than on the climactic ‘Give Up The Sun’. Far from self-pitying anguish, this is a lament that sees "gulls pick at bones and glass" on a beach surrendering its inherent beauty as all around the familiar and comforting sights of times gone by are given little if no respect. The loneliness of ‘Bad America’ is palpable throughout as the vulnerable are discarded and ignored ("and there’s vein-like children on the waterfront/smack rotting faces on the waterfront"). Yet despite the lachrymose observations, the music is strong and strident and the effect is akin more to that of defiant rebellion than powerless surrender.

The Las Vegas Story stands out in The Gun Club’s sizeable body of work. Born against a background of adversity and fighting back, this is a re-birth that burned brightly and intently but one that wouldn’t – couldn’t – last. Leaving Los Angeles to take the album on the road for a tour that would see them delivering some of the most accomplished and devastating performances of their career, the band little realised that they wouldn’t be returning home or hold together much longer as a unit. A combination of personality clashes, financial mismanagement, theft and simple bad luck would conspire to decimate The Gun Club before the year was out. They returned several years later with another line-up and the brilliant Mother Juno album but at this point in time, The Las Vegas Story was an artistic pinnacle from a band that had already claimed and justified its uniqueness. This is an album that has weathered the years well and still stands the test of time thanks to its universal themes that, for good or ill, are as relevant now as they were then and a quality of playing that was driven by a bold and daring vision, and a desire to give rock and roll a new lease of life in an ever-increasingly mechanised world.

Perhaps all farewells should be sudden but the continued power and magnificence of The Las Vegas Story ensures that, even in the face of Jeffrey Lee Pierce’s mortality, this is going to be a long and drawn out goodbye.

What were the circumstances surrounding your departure from The Cramps and your return to The Gun Club?

Kid Congo Powers: A few different things happened. I started hanging out more with Jeffrey (Lee Pierce) and The Cramps were on a bit of hiatus. They were in a bunch of legal trouble wrangling with their record company and so not playing often and definitely not recording… and I just wanted to make music. The Cramps had recorded The Smell Of Female album but it still hadn’t come out.

I was getting antsy to do something else and I think they wanted to do something else; they started using bass guitar after I left whereas it had been just two guitars up until then. But there were other things. I was taking a lot of drugs and that’s not so great for creativity. But at the time Jeffrey was going to help make a solo record for me. The Cramps had said, "Well, we don’t know what we’re doing", and I said, "I’m thinking of making a solo record." So they said, "Perhaps you should do that." So that was the end of that but it was an amicable parting of the waves.

Jeffrey then went off on a tour of Australia with The Gun Club and a few days later he called to say, "My band quit at the airport and only Patricia is here and can you come to Australia tomorrow?" I said, "Well, I’m a free agent now so I’ll come." So ended up not making a solo record and coming back to The Gun Club. Jeffrey already had some songs for The Las Vegas Story at that point. I remember on that tour we were playing ‘Eternally Is Here’ and ‘Moonlight Motel’.

What did you bring from The Cramps to The Gun Club?

KCP: A distortion pedal! In The Gun Club before, we didn’t even use a distortion pedal or anything so it was all very raw and very basic. The Gun Club was very, very influenced by The Cramps, actually. Maybe I brought a certain heaviness with me? The Las Vegas Story was the time that Jeffrey started playing guitar again so there was a lot more weaving in and out of the guitars. In The Cramps I was either the rhythm guitar player or the bass player using a guitar so I learned to play more.

Compared to its predecessors, The Las Vegas Story sounds like a fresh start for The Gun Club. Was that the intention?

KCP: Yeah. Jeffrey was looking to do something different than he had done before. We discussed this often because the minute people tried to pigeon-hole us we wanted to do the opposite. We wanted to run away from what people might want us to do. It was a bit bratty but it was also a survival technique. And Jeffrey was exploring playing guitar a lot more and we were kind of iconoclastic in way with old music; we didn’t want to be a roots band or roots snobs. We were very much into finding new things via old music and interpreting it in a new way. The Cramps, James Chance and The Gun Club, we were all fans and record collectors of old music but the expression came out of the present. It definitely wasn’t to be nostalgic. Nostalgia was a no-no.

I understand that Tom Verlaine and John Cale were high on your producer wish list. What did you think they had to offer? Why didn’t they get the gig?

KCP: I think it’s very obvious that we had a huge Television influence on this record and a love of their music. John Cale had produced many great records from The Stooges to Patti Smith to Nico and you know, John Cale is John Cale! Who would not want John Cale? But I think these were sounds Jeffrey and I wanted to incorporate into the newest version of The Gun Club. I guess the word ‘darker’ keeps coming up and John Cale was certainly darker with a sense of exploration of sound and interpreting sound in a visual kind of way. Jeffrey’s lyrics were very visual and our thoughts about music were very visual and we referenced film a lot. And we wanted Tom Verlaine for similar reasons. The sound of Television had a certain absolute beauty that had a raw, wiry sound and The Gun Club was going for beauty. That was our goal – a certain liquidity that had a spectral, otherworldly sound and something more mind expanding.

How was it working with producer Jeff Eyrich?

KCP: Also on our list was David Lynch. We also had two other ideas that absolutely no one would let us do. One was David Lee Roth just because we thought that he would tell us really good jokes and the other one was that we should have Vanity 6 because we thought that way we’d have Prince producing us and then we could get lots of great photos of them in lingerie painting their toe nails at the mixing desk.

Is it true you used Ry Cooder’s equipment when he was out of the studio?

KCP: Oh yeah! When we couldn’t get John Cale or Tom Verlaine for logistical reasons and we listened to this T-Bone Burnett record that Jeff Eyrich had engineered and produced and it was really great. It was very beautiful and moody so we picked him based on that. This was at the time when we were still on Animal Records which was Chris Stein’s label and they got us into Ocean Way studios in Hollywood doing the graveyard shift between midnight and 6am and we had a lot of the material ready and pretty well done before we went in.

Jeff really helped us a lot and he got us into Ry Cooder’s studio and he had all this great vintage equipment and all these strange percussion instruments and we were like, "Oh! Very nice!" He asked if we could use the equipment and we used these whirling whirlies which were like these long serrated pipes and you’d swing them around your head and they make a wind sound. It was funny because one day we were there and Jeffrey picked up the whirling whirlies and started swinging it around and then a friend of ours, Fast Freddie, was there and he picked one up and then Terry’s wife went in and picked one up so I then got one and we started making this crazy wind sound which you can hear at the very beginning of the album. Luckily, Jeff Eyrich was in the control room and said, "What’s going on in there?" So he just got the tape rolling and recorded us. We didn’t even know it was being taped so that was a fortunate accident. And many good things happen in the studio that way!

The album feels like a musical reading of Charles Bukowski. Did his writings inform the album? Were there any other literary influences?

KCP: Oh, definitely so. That was the time that Jeffrey was pretty much living with me and that was a great time. We were very into the Beats; Jeffrey was a very big Burroughs fan – as we all were – and we were really revelling in Bukowski, Ginsberg, Gregory Corso, Brion Gysin, Malcolm Lowry; Under The Volcano was passed around a lot and we passed it on to Nick Cave as well reading a lot of Joseph Conrad and Heart Of Darkness. We were influenced by the way the Beats used language. We were reading tons of that and listening to a lot of jazz. Obviously we did a little homage to Pharaoh Sanders with ‘The Creator Has A Master Plan’. At that time, we were definitely be-bopping.

There are a surprising number of jazz influences on the album – Pharoah Sanders’ ‘The Master Plan’ and Gershwin’s ‘My Man’s Gone Now’. You also covered John Coltrane’s ‘A Love Supreme’ on the tour. What drew you to jazz?

KCP: That style of jazz has its own language and it speaks to you. You understand it and it has a definite feeling, disjointed as it seems, but it seemed very coherent to us. The lesson that we learned from it is to listen to music and create a language and that’s what those records did. Not only a language that you can understand but a language that people want to learn. That’s the way jazz is; it’s a whole education of sorts and it says things in a different way and in those jazz influences that I mentioned I understood that they were expressing something soulful and it hits you on that level; it hits you in the soul.

We didn’t try to transpose it to rock & roll but Jeffrey always used to say, "Hey, let’s think like jazz!" We weren’t jazz players and we can’t play jazz but we can make our own version of it and that’s what did; we made our own language so people of our language could understand that language. We more interested in the feel of it rather than a note-for-note execution. That was the goal.

What chemical influences informed the album?

KCP: At the time of work and making music and recording, we didn’t do anything in the studio. We wouldn’t have got anything done if we had. If we were keeping any habits then they were at the minimum. As crazy and wild as we were, we knew that when it was time to work then it was time to work. The work was the most important thing and it had to be great. Working in the studio was not a time to indulge. But the minute the record was done…

The album was recorded and released in 1984 – the year of the LA Olympics and the re-election of Ronald Reagan. Clearly change was in the air. Can The Las Vegas Story be viewed as a farewell to a time and place that’s now gone and is unlikely to happen again?

KCP: Yes. It wasn’t conscious but in retrospect, it definitely can be seen as a goodbye. We left America and moved to London after The Las Vegas Story tour. Me, Patricia and Jeffrey ended up staying in London for many years. There was an increasing amount of disgust with a certain kind of nationalism that seemed to be coming over the country and LA in particular. And the re-election of Reagan – you couldn’t believe it had happened because it had been such a horrible first term for many people.

Also, the whole AIDS epidemic had happened so we were losing friends left and right and the Regan administration wouldn’t even address the fact that it existed. In that, we were staring to see a certain nationalism and we could see it seeping down into music and bands; not just John Cougar Mellancamp but also into local bands who were then suddenly playing with an American flag behind them or getting very much into roots music which was something that we had been doing but our attitude was to change it all. There was a certain wave of nostalgia and nationalism coming into the underground and we felt a lot of disgust with that.

With the Olympics coming to LA came the tearing down of old buildings and that didn’t sit right with us at all. We were all in very big agreement that we would just leave the country and not come back until it was better. By the time I got back, Bush Snr was the president [laughs] so there goes my protest!

The Las Vegas Story was definitely about a time of change. It’s a very different sounding record from the others as is the mood. It was important not to become stale or a cliché of yourself.

What was the mood in the band when you took the album on tour? It was quite the extended excursion, wasn’t it?

KCP: Well, we started off disgusted with the country and ended up disgusted with each other! But, you know, Jeffrey had a difficult, difficult personality. And we used to drink so much all of the time. We used to take drugs but we decided not to take so many drugs and instead to drink until we blacked out every night. We thought we were really going for it but that self-destruct button was definitely being pushed 24/7.

But the mood of the band was really very good even though we were just crazy but the shows could be really incredible. We were doing a lot of improvisation and going of on all these musical excursions. I can remember once saying, ‘Wow! When did we become the Patti Smith Group?’ Y’know, ‘Preaching The Blues’ was like ‘Horses’! It was great, I felt great and the band was just great. Terry Graham’s drumming was amazing and so we managed to follow Jeffrey on whatever tangent he was going on.

Unfortunately, the personal side of things was less great. Jeffrey, quite often, could be pretty insufferable and very selfish. It made problems for the other band members. I was already friends with Jeffrey so our relationship was a little different but the other band members felt disrespected and not appreciated a lot of the time. Jeffrey wasn’t one to tell the band, "Oh, that was good!" He wasn’t a great communicator.

And then, later in the tour, Terry Graham just left. That really set us back and it became impossible to do what we’d been doing without him. We got another drummer and he worked out OK. He could play the songs but as for any improvisation and any kind of magic, well, we just couldn’t do it. When Terry left, that was the end of The Las Vegas Story tour, really. We carried on and continued in another form but that whole period was over.

When did the band start unravelling and what do you think contributed to its demise?

KCP: It all started unravelling the first time Terry quit the band when they were going to Australia! I was pretty shocked that Jeffrey took him back. He was an incredible drummer but he was a very big complainer – everything was horrible all of the time – and he had a very tempestuous relationship with Jeffrey – I don’t think he liked him very much.

Then, on tour, we played the Hacienda in Manchester and we’d left our suitcases in the tour van which then got robbed. Terry had been filming everything on Super 8 and all the tapes got stolen. I think that was his last straw and it was a personal freak-out after being on tour too long with Jeffrey Lee Pierce. A typical story!

With the benefit of 30 years hindsight, how do you view The Las Vegas Story now?

KCP: I’m extremely proud of it because it’s the most different of all of The Gun Club’s records. It stands out on its own and it hangs together really well. It was a very great production; I have production issues with the other records but not on this one. And I think it really captures the mood of the times of America in general and LA in particular. It has that feeling of doom and disgust but it’s also been made to be quite beautiful. It was a time of exploration for The Gun Club and it had a lot of jazz and literary influences on it. There was also a lot of likemindedness with other bands like The Birthday Party and other friends of ours.

But there was definitely a change in the times; the records before it and the records after it don’t have that mood. It’s very dense and intense. I get a lot people coming up to me on tour these days and they tell me how important The Gun Club and that record was to them at that time and I appreciate that greatly. It was a great time and one where The Gun Club matured but still hit a nerve. It was view of America but maybe that view was global because people from all over the world tell me how much that album means to them.