If they were giving out awards, no-one would be able to accurately predict the winner of the category: but the Fugees would be in with a shout of being the most widely and comprehensively misunderstood band in the history of popular music. Their second LP, The Score, sold umpteen millions around the world, turning them into one of the biggest bands on the face of the planet for the final years of the last millennium, but sales did not reflect a critical consensus that lazily labelled them an unbalanced trio with one genuinely world-class talent sharing space with

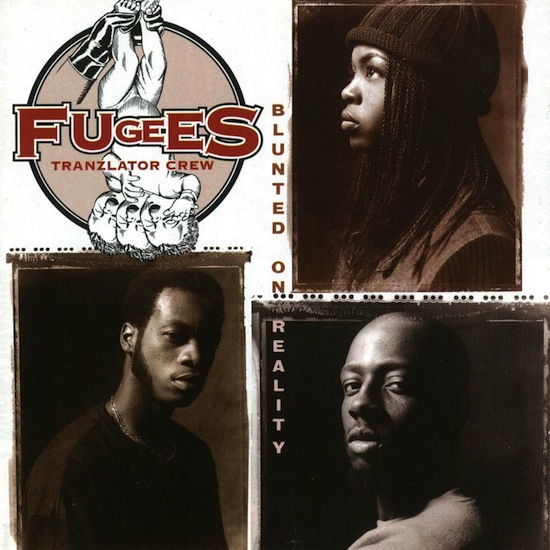

two shameless chancers. Perhaps it should come as no surprise, therefore, that their debut seems now to be largely maligned and roundly misinterpreted: after all, even the people who made it, on the few occasions they’ve discussed it in public in recent years, have talked about it solely in terms of its flaws and failings – of which, certainly, there are more than a couple. But Blunted On Reality – a commercial flop 25 years ago, which went on to sell around three million copies after The Score transformed the group into global superstars, and all but ignored entirely today – is a record that deserves a reappraisal; as does the mercurial career of the band that made it.

They were called the Tranzlator Crew to start with, a name that remains as a vestigial appendage in parentheses on Blunted…‘s sleeve (by 1996, and The Score, the subtitle in the band name had changed to Refugee Camp). It came from multilingual Wyclef’s habit of switching,

mid-song, between Creole, Spanish and English during the band’s early live shows. The Crew were formed by Clef and Praswell, children of Haitian emigrees relocated to New Jersey. Multiple reports describe them as cousins, but they’re not blood relatives ("When we beefin’ we’re not cousins!" Clef joked with me in a 2006 interview. "Since he was little we put him under our arm. He was much younger than us – he only looked older! We always was close as little kids"). Pras had a band he’d put together at school with two girls, one of whom was the much younger Lauryn Hill; over time, the two projects converged, and the membership settled down as the two Haitians and the Brooklyn teenager. The ethnicity became a defining factor, giving the band their new name (an abbreviation of "refugees") and supplying several tracks on their debut with a primary theme.

They did the rounds of New York labels without any luck, until an audition with Chris Schwartz, head of the Columbia-funded imprint Ruff House, led to a deal for an album. Accounts of that fateful private performance vary, but most seem to indicate that the trio rapped over Clef’s acoustic guitar (at the height of anti-Fugee mania in the late ’90s, it became a critical shibboleth to label Clef as someone with such an absence of talent that his "one time, two time" ad lib on the cover of ‘Killing Me Softly’ which was crucial in gaining the band a mass audience was the limit of his musical capabilities; if anyone had bothered to check, or even if they’d listened to his 1997 solo album, The Carnival, they’d have found abundant evidence of his capabilities – he plays at least 15 different instruments, and has written and/or produced hits for everyone from Destiny’s Child, Whitney Houston and Shakira to Sinead O’Connor, the Neville Brothers and Tom Jones).

Ruff House was just getting started, but had created a stir with their first big success, Cypress Hill, whose 1991 debut shook up gangsta rap, and whose follow-up, 1993’s Black Sunday, established the band with an alternative rock audience. The means by which this was achieved has relevance to the Fugees narrative: Cypress’ emcees delivered all the machismo and steely eyed cool that gave gangsta much of its allure, but refrained from indulging in the bulllshit attitudes towards women which inevitably put off plenty of people who might otherwise have dug the beats and the attitude (on the first track of their second album, the only appearance of the kind misogynist language rife on many of their contemporaries’ records was a sly little joke: "Catch a ho, and another ho – merry Christmas"). Coupled with an iconic logo design, some cool merchandise, a widespread interest in the legalisation and industrial-scale consumption of marijuana, and not just an energetic and entertaining live show but a willingness to play the rock festival circuit (Cypress weren’t on the first Lollapalooza bill, but were so much a part of what it came to mean that they were a shoo-in for inclusion when The Simpsons parodied it in the ‘Homerpalooza’ episode), the band became probably the only properly hardcore rap outfit of the period that indie kids felt OK about liking. How much of this was down to the band and how much to canny strategising by the label is open to some debate, but what is clear is that, by 1994, Ruff House was becoming the imprint to turn to if you had genuine hip hop in your blood, but could also put on a good live show and wanted to get your records heard by people who didn’t listen exclusively to rap.

Blunted…, therefore, didn’t come out of nowhere. Recent critiques have connected the record’s sound – very different from the Fugees of The Score, and therefore justifiably worthy of note and attempted explanation – with other New Jersey hip hop of the day, particularly

Naughty By Nature. It’s a fair point, but a much closer cousin, sonically, is Tricks Of The Shade, a magnificent and oft-overlooked debut by Fugees’ Ruff House labelmates, the Goats. Both records share a sprightly, bright-sounding production, with guitar lines (whether sampled or played) prominent against limber bass and snarling, snapping drums. In particular, compare and contrast Tricks of the Shade single ‘¿Do the Digs Dug?’ with Blunted…‘s de facto title track (it’s clearly intended to be ‘Blunted On Reality’ – the chorus is "Some thought we were blunted when we wrote this/ Because we were far from reality" – but it doesn’t appear on the track listing, oddly turning up hidden behind the 80-second skit ‘Blunted Interlude’).

The two records had different production teams – Tricks… is credited to Goats founder Oatie Kato and Joe "The Butcher" Nicolo, co-owner of Ruff House and remixer of Nas’s first single, ‘Half Time’, while Wyclef and Pras share production credits on Blunted… with a raft of others. Most prominent among them was Khalis Bayyan, born Ronald Bell, and a founder member, alongside his brother Robert, of Kool and the Gang. So, for all the differences, in each case Ruff House was prepared to allow new bands to give sonic direction to their debuts, and provide

experienced associates to help achieve an end result that was cohesive to listen to and professionally recorded.

Another similarity, and a quality of Blunted… that seems largely to have passed by most recent re-reviewers, is that both records explored lyrical themes of racial division and societal breakdown. Tricks Of The Shade was a much more focused piece of polemic – Kato, a

Chomsky-reading leftist, instigated the record’s concept (a tour around contemporary America rendered as a grotesque carnival freak show). But for all its diffuse takes on America’s problems, Blunted…, too, is an often strident political record, one that offers solutions amongst its

identification of problems, yet which encourages its views on the listener rather than demands they pay attention.

The other main aspect commentators, critics and the ever-growing number of cynics appear unable to hear in Blunted… is its adherence to hip hop’s foundational values. Those who insist the music is about rigid adherence to set styles, whether musical or lyrical, don’t really get it: the true test of the worth of a hip hop artist is their interest in, and aptitude for, experimenting within the form. Inevitably, this means that the most innovative and fearless hip hop artists will fail some of the time. What is important is not the number of times they succeed, but that they try to do something new. And Blunted on Reality shows a group, still finding its feet, who are more than up to the challenge the music’s history has set.

That Ruff House audition is recreated midway through side one. ‘Vocab’

might not sound too special today, in the post-Timbaland era, when sonic

source material routinely takes in all sorts of instrumentation and it is

no longer daring to leave mixes stark and with space between the elements

of the production: but 25 years ago, a band rapping over just an acoustic

guitar – for an entire song – was unheard of.

That the song itself is about communication, the very essence of the art of the emcee, is entirely

apt given that the newcomers who dreamed it up were all about finding new ways to speak out. (They didn’t limit themselves in any way whatsoever: the version released as a video is completely different – a new backing track with entirely new lyrics, the only similar element being the hook.)

If they were known at all back then, it was for the Tranzlator Crew shtick – for speaking in tongues. ‘Vocab’ was – is – a revelation. But the Fugees weren’t the first prophets to go without honour in their homeland.

Even when the record sticks closest to established hip hop forms, the vocal styles and modes of delivery the emcees bring to the mic frequently dazzle. The first verse on the record – Wyclef’s on the thwacking thump of ‘Nappy Heads’ – is a case in point. "Why am I trapped in a cage?" he screams at the outset, then thrashes about inside the space he’s metaphorically confined to, like one of those explosive moments in a Tom & Jerry cartoon where one minute the head’s massive, the eyes on stalks, the mouth framing a scream, then the next he’s standing there, all meek and

mild, like butter wouldn’t melt, before the next convulsion hits and another unexpected and instant transformation occurs. A handful of lines in and he’s whispering; seconds later doing a dead-on impersonation of a rapping Louis Armstrong. Later lines find him dancing between a series of

different polysyllabic flows – triplets here, double-time there, tongue-flipping everywhere. As if knowing it’s wisest not to compete directly, Praswell’s following stanza includes a short interlude for Lauryn to proclaim herself "a cool chief rocker" who "never drinks vodka".

We’re only three minutes into the album but they’ve already broken half a dozen rules and the boundaries of the art form have come unhitched from their moorings and are off, rolling uncontrollably ahead of them like a drift making way for a snowplough. (And, again, the version released as a single – a remix by Salaam Remi – is entirely different.)

Thematically inauspicious her first lines on an album may have been, but Hill quietly and quickly becomes the record’s ear-catching focus. That’s the one part of the consensus on Blunted… that feels like it’s right: she was exceptional from the start, and a storied solo career was

clearly hers for the taking. As the non-Caribbean member her contributions to tracks that blasted anti-Haitian racism were always going to carry a different kind of power, but her verse in ‘Refugees on the Mic’ ("I rip on the real tip/For the righteous situation/Interpretation of degradation/Your race relations and education/Segregation/Emancipation/Or capitalisation/Integration not separation/Yo, free the Haitians") goes above and beyond. What’s more than peculiar, though – it remains as bizarre an occlusion from the historical record as a clear and unambiguous sense of what on earth happened to Hill between MTV Unplugged 2.0 in 2002 and that amazing Trace magazine interview three years later – is why the wonderful ‘Some Seek Stardom’ was, a) never released as a single, and b) not singled out in every last thing ever written, said or thought about this album as its unambiguous standout moment.

That isn’t said lightly: by highlighting Hill’s one solo track, one risks being misinterpreted as toeing the conventional line that the two blokes have nothing of worth to contribute – which couldn’t be further from the truth. Pras was never going to make anyone’s Top Ten emcees list, but – notwithstanding his and Clef’s apparent lack of regard for this album – he’s at his best throughout, inventive and characterful as he gnaws and spits at the lines with a gurgling flow that anticipates some of the scenery-chewing antics to be found on the following year’s Ol’ Dirty Bastard album. And Clef, though he would later top his performances here, is still reliably and consistently great: the abundant versatility of his raps is allied to a restless sense of stylistic experimentation and innovation, and his lyrics mostly rise to the occasion. His line in the title track about "my brain keeps moving like a body on a horse" is a terrific image, striking and unusual yet expressed with clarity and simplicity. Both give often spectacular displays of the art of the emcee on this record, dropping verbal pyrotechnics across the beat, relishing the wordplay and coming up with innovative and ear-catching ways of putting words to music.

That neither of them can reach the heights Hill does on ‘…Stardom’ is less to do with their lack of ability or capability than it is the incredible heights the teenager reached on this album, and on that song in particular. It’s not just one of the best hip hop tracks of all time, it’s one of the best songs full stop. And the space in which she was able to make it – indeed, the creative environment that meant she felt ready, willing and able to essay something so precious and remarkable – was one that the three Fugees created together.

Over a beat fashioned from a cover of ‘Bridge Over Troubled Water’ by Aretha Franklin – talk about auspicious – Hill gives what is surely one of the greatest vocal performances of the 20th Century. Simply on a formal basis, the song is flabbergasting: she switches between rap, bluesy jazz scats and singing – only it’s the sung parts that often ring with the syllabic quality of rap, and the raps that carry melody, timbre and soul. If her vocal line was transcribed and played on a stringed instrument it would be baroque, bizarre, beguilingly complicated – not that melodic intricacy, in itself, is particularly interesting or valuable. There are flashes of this throughout the album – the brilliant verse on the title track where she constructs a freeform narrative out of piratical subject matter and nautical references, before ending it with a line ("and I took it upon myself to make the brother walk the plank") she delivers with the playful and innocent invention of a giggling girl playing a playground skipping game. But none of this would matter nearly so much as it does without something of substance being said, and in ‘Some Seek Stardom’, Hill ticks that box, too.

The song’s theme is people who leave their roots behind them when money and success beckon – people who "seek stardom" but "forget Harlem," who "keep their pockets full" while their "souls run empty." Listening today, you’re tempted to see where she is now, look back through where she’s been to get there from this starting point, and conclude that she’s fallen foul of the same temptations she warns against here. And it’s undeniable that the journey has been a curious one: from the apparently uncomplicated if undeniably precocious young woman on show here, who fuses jazz, hip hop and soul in vocals of unprecedented and frequently breathtaking invention,

filled with the sheer joy of uninhibited creativity – through the solo album and the record-breaking Grammy haul, and the marriage and motherhood and absorption into the Marley dynasty; then on beyond into that strange and aloof world where even her bandmates had to call her "Ms Hill" to her face, and up to today, where it’s like she’s out there on her own, buried deep beneath pop culture’s seabed, digging in the darkness, quarrying out the occasional musical jewel before dropping it into our perennially ungrateful hands, accompanied by a defensive Tumblr post about how the American tax laws shouldn’t apply to her because she’s an artist. But… Look: not only is Lauryn Hill among the greatest emcees ever to pick up a mic in anger (or in compassion and boundless understanding, come to that), she’s one of the last of the old school of bona fide musical treasures we have left. So what if she approaches things differently? That’s what we need artists to do.

And in a sense, it’s all laid out here, in the three dizzying verses of ‘Some Seek Stardom’, where Lauryn – riding that Aretha organ beat – takes us to church, walks us through the streets, shows us the hypocrisies and contradictions of today, and points out two possible tomorrows: one that

we can build on a foundation of lies and self-loathing, and the other where integrity and honesty ride a spiritual vibe onto a higher plane of understanding. "I flew away on a mountain, got tempted by Satan/Got bitten by a snake but the Lord took my venom," she tells us, matter-of-fact, like you would if you were talking about a trip to the shops the other day. "So whose side am I on? I’m on the righteous."

That’s verse one: verse two is the one where she really goes to town. "In my brief history I can’t neglect my past," she says by way of explanation and warning for what’s about to come – a hypnotic mist of mellifluous syllables, strung together with the quality of a Catholic priest’s

psalm-singing, going back to Bible school to explain where she comes from and what values she stands for and embodies. You intuit its meaning first from the sounds, long before you confirm it by studying the actual words (and, for what it’s worth, after 25 years and thousands of listens, there are four lines in the middle there where it still feels like an accurate transcription is impossible: yet arriving at one also seems entirely unnecessary. It’s like trying to understand van Gogh’s Starry Night by compiling an inventory of the brush strokes, or attempting to write a coherent paragraph about what a Coltrane solo means). It builds to a kind of a climax, albeit one both characterised and underscored by the effect of chasing truth through the fog that the delivery of the lyric conjures: the final lines find a woman wise beyond her years examining questions of social, familial and spiritual acceptance. It’s not Christ on the cross asking why God has abandoned him, but there’s an echo of that in those provocative closing lines: "At last I clearly see what’s wrong with me/See through your insecurity of me and my ability/So bredrin, won’t you let me be?/Or hast thou asked too much from God to tell the truth and not to lie?/Oh my…"

The final verse is straightforward – the message of the song, laid out clearly and unambigiously, and sung for extra emphasis. The link from the previous stanza’s recollections of childhood is bridged (over Aretha’s troubled waters) with a simple but clever bit of back and forth, forth and back: "As I grew, I knew, ‘cos the master told me/from a baby to a woman, from a woman to a baby" before Hill dives in to the final exposition of her argument. It wasn’t particularly new to note the tendency of some self-made people to leave where they came from the minute that success comes calling, rather than offering a hand to the folks they’d grown up with, but she expresses it with a rich and poetic eloquence. And then, in a final flourish – the artist signing the canvas after completing her masterpiece – she calls out to her producer, who’s waiting in the wings: "Oh Khalis man, you c…" She interrupts herself, stops, starts again: "Come on, you can blow now if you want to – we’re through." And for the first and, so far, the last time in hip hop history, the song ends with a clarinet solo.

There was more, of course – much more. The record stiffed, but Schwarz gave the band $130,000 and told them to go away and make a follow-up; they invested the money in a home studio, Pras and Clef took Salaam Remi’s advice (he had pointed out to them, during the ‘Vocab’ remix session, that the mics were going to record them whether they were shouting or

whispering, so they didn’t need to come off like Onyx), and The Score went on to conquer the globe. That the group fell apart, with Clef and Lauyrn’s affair turning them into a hip hop Fleetwood Mac, is one of pop’s great stories; and the three careers that followed, and the occasional attempts at reunification, remain fascinating case studies of what to do and what not to do in the music business. But Blunted On Reality is much more than a footnote to the pre-Score career: it’s part foundational and part inspirational, and wholly involving and

affirming if you open your mind and let it in.