There is a theory – ascribed by Dave Simpson in his book The Fallen to former Guardian film and music editor and tQ contributor Michael Hann – that your favourite Fall album is the first one you heard/bought/admitted into your life. The thesis here is, to paraphrase the band’s biggest fan, the same, but different: this writer would argue less for your first Fall album as becoming the personal stand-out than the first Fall line-up you succumbed to. In part, this is because, much as I love the first Fall LP I bought, I really can’t pretend that Totale’s Turns is the best thing they ever did. But the version of the band that existed from the point that record was released – if not from the moment it was recorded – is certainly the one that feels like the defining iteration of this most confounding and beguiling of countercultural institutions.

Like the band throughout its uncommonly long and tortuous history, each of us is always a work in progress, so our feelings will change along with the subjective realities that shape them and the replacement of cells in our bodies; but whatever else is happening in and around the place he inhabits, it’s The Fall of 1980 that your correspondent keeps coming back to and finding new wrinkles and nuance to dive back amongst and delight in. For many listeners – and perhaps even in an objective analysis, were such a thing ever to be possible – it is the two-drummer line-up of Hex Enduction Hour that represents The Fall at their unbetterable zenith; for others, it’s the less fixed but sonically consistent iteration of the band that made that run of three brilliant LPs for Beggars Banquet between 1984 and 1988. For all that the mere mention of the name immediately calls to mind the constant churn of band members and the unending process of upheaval in their five-decade evolution, it’s hardly a surprise that many of the records that remain high on fans’ lists of favourites were made by relatively stable line-ups. The Fall of 1980 – at least, the version that made it to the studio – was one such.

Their year began with the last gasp from the group’s first act. ‘Fiery Jack’ had been recorded in the autumn of 1979 and became the band’s last single on Miles Copeland’s Step Forward label when it was released in the first month of the new decade. Pretty much as soon as it was out, so was former rockabilly band drummer Mike Leigh. His replacement would be bassist Steve Hanley’s kid brother Paul. Marc Riley, having joined as a bass player, was now ensconced on guitar and keyboards; he, the elder Hanley and guitarist Craig Scanlon (rendered "Scanlan" on the ‘Fiery Jack’ sleeve) had all been in place since the making of the previous single, ‘Rowche Rumble’, in the spring of 79. A colourful quote would, years later, famously be attributed to Mark E Smith, to the effect that whoever else might be involved, as long as he was there, then the band was The Fall: but to most of us who learned to love and live with this strange, demanding and compelling music in the moments it was being made, The Fall were never really The Fall unless Scanlon and Steve Hanley were involved. (This is as true for the first two singles and debut album as it is for anything released after 1998.) And, of all the line-ups to feature both of them, it is the one where they’re in train with Paul Hanley and Riley that feels somehow definitive.

And yet, and yet… May 1980 saw the release of Totale’s Turns (It’s Now Or Never), the first of what the mammoth online resource thefall.org lists as 42 officially sanctioned live Fall LPs. It was the first Fall product to appear on the Rough Trade label, run by Geoff Travis, who’d co-produced ‘Fiery Jack’, so is in many respects less part of the new-look group that were taking shape as the year drew on than a product of the version that Leigh’s departure had just closed the book on. Why, then, does it feel like the first salvo from the new band rather than the last testament of the old one?

To describe Totale’s Turns straightforwardly as a live LP isn’t quite accurate: it includes one studio recording – the slight and light yet punchy pastiche ‘That Man’, an outtake from the October 79 ‘Fiery Jack’ sessions – and one deliberately low-fi cassette-recorder home demo. (In a sense, the version of ‘New Puritan’ included here ends up by default being the definitive one: the track was never re-recorded for a Fall studio LP or single, only for a John Peel session; it was that version which was eventually released as a b-side during the band’s second stint on Rough Trade.) It is only on ‘That Man’ where the clicky, ticky drum shuffle Leigh obtained when in the studio as a member of The Fall is apparent: without diving into the murky waters of live bootlegs it’s impossible to say whether the sound he got on stage was more representative of his playing and of the band’s overall approach at the tail end of 79 when the Totale’s Turns material was recorded, but taken as a whole, the LP has more to connect it to the studio Fall to come than the studio Fall just gone.

Side one of the LP was recorded at a leisure centre in Doncaster and features the group (introduced by Smith at the outset as "The Mighty Fall" – which seems to be the first time that construction was coined) at arguably their most rock & roll. Given the invariable association of Smith and his band with whatever the opposite is of adherence to convention or following accepted music-business wisdom, the record opens with the band’s two most recent singles, though things thereafter skew swiftly and satisfyingly away from such sops to mainstream acceptance. ‘Muzorewi’s Daughter’ is as confounding as it had been on the previous year’s Dragnet studio album, its reading here strained as the band members push power ahead of precision. ‘In My Area’ – as good a song as ‘Rowche Rumble’, the single it appeared on the flip side of – is a moment of comparative quietude rendered unsettling by acerbic electric piano. The side closes with ‘Choc-Stock’, a song carried over from Scanlon’s previous band, and it may not just be needle flare on my ancient copy of the vinyl that renders it chaotically distorted by the end. Side two revisits two more Dragnet curiosities – a rattle through the second half of ‘Spectre Vs. Rector’ and a splenetic, doomy ‘Cary Grant’s Wedding’, recorded in Bradford in February of 1980 – lobs in the deliciously incongruous ‘That Man’ and the near-impenetrable curio reading of ‘New Puritan’, and ends with a frankly terrifying version of the first album’s ‘No Xmas For John Quays’, Smith breaking off mid-line to berate the sound engineer before turning on his own band. "Idiosyncratic" isn’t the half of it.

Paul Hanley was still at school, so after half a dozen gigs in the UK he had to briefly cede the drum stool for a fortnight in June when the band toured Holland. From the end of that run of gigs and up to a US tour in 1981, though, everything The Fall did – gigs, studio recordings, Peel sessions, the semi-official live album released at various points as Live In London 1980 and The Legendary Chaos Tape – was with the Smith/Riley/Hanley/Scanlon/Hanley line-up. The first fruits were two songs recorded on 8 May at Cargo Studios in Rochdale and which perhaps better typify the Fall of the time than anything else. ‘How I Wrote "Elastic Man"’ and ‘City Hobgoblins’ were released on either side of a 7" single by Rough Trade on 11 July and are perfect encapsulations of everything that was great about this particular incarnation of this perennially fascinating band.

Ramshackle yet metronomic, the parts individually simple but almost impossibly complex when combined, these songs – at once both brittle and sonically indestructible – offer a microcosm of the band’s collective genius. ‘Elastic Man’ opens with a high-tension ping of a guitar line clearly designed to echo Status Quo’s ‘Pictures Of Matchstick Men’ before quickly resolving into four minutes of punishing, brutal riff, industrial clanking given song form and played as if a hellhound was snapping at their heels, over and within which Smith spins a yarn about a lauded sci-fi author whose fans want to understand how he wrote his most acclaimed work but who can’t even render the title accurately. Today’s listener will likely think of an Alan Moore-type figure (seven years before Watchmen, of course), doomed to be chased by acolytes largely oblivious to the depth of his talent, whose interest is more about them than their supposed hero; back then, perhaps the template listeners inclined to dig deep would have had in mind was a Kilgore Trout kind of figure – between the "article in Leather Thighs" and muted acclaim from the Observer Magazine, the protagonist’s career trajectory seems similar to Kurt Vonnegut’s high-output, low-income fictional doppelgänger. Yet in a self-made interview recording from 1980 included on some versions of the Grotesque reissue CD, Smith first says the song is

"about how the public kill off their heroes’ creativity" then adds: "I was talking more about Jimmy Greaves, George Best: if you don’t believe me, just ask them. Biographical!"

Smith’s choice of subject matter, if not writing style, would gradually change as the 1980s drew on, but two of his predominant themes are illustrated in proud relief on this single. The A side can, albeit only if you squint a good bit and hold the thing at some distance, be viewed as not biographical, but autobiographical, similarly to how some readers perceive Trout to be a substitute in certain aspects for Vonnegut. Smith may well be hiding a version of himself – set upon from all sides, his most ardent admirers proving to be his worst nightmare – within a character study, much as he would do to career-defining effect mere months later on ‘Hip Priest’, and had perhaps started to essay on ‘Fiery Jack’ and in bits of ‘New Puritan’. (Indeed, ‘New Puritan’s obviously lowly place in his estimations – if we’re going by its lack of a definitively "finished" version – appears particularly striking, given its evident status as a staging post on the route to ‘Hip Priest’. Then again, maybe once Smith had minted the latter, he felt no need to have another stab at its precursor. Or maybe he felt that the Totale’s Turns version was both first and last word.) The difficulties inherent in the act of literary creation remained a preoccupation and often fuelled some of Smith’s finest work – see in particular ‘Garden’, from Perverted By Language, surely the point at which his explorations in this direction reached, if not a destination, then a point from which it would be almost impossible to press on any further.

‘City Hobgoblins’, meanwhile, only seemed a bit less remarkable at the time because it fitted very neatly into the Fall subset of paranoid psychodramas with supernatural overtones that accounted for getting on for a third of Dragnet‘s track listing (not just ‘Spectre Vs. Rector’ but ‘Flat Of Angles’ and ‘Psykik Dancehall’ clearly fit the mould, while there’s elements of something hiding just beyond the bounds of the tangible that haunts the album’s best tracks, ‘A Figure Walks’ and ‘Before The Moon Falls’) and bits of Live At The Witch Trials too. It’s notable that a good part of his best lyrics are found where he gives free rein to the fiction writer living inside: much as his status in later years as irascible national treasure relies on the moments in his music where he most conspicuously draws from the wellspring of his own lived-through experiences (‘My New House’ and ‘No Bulbs’; ‘Carry Bag Man’; the aforementioned and unavoidably pre-eminent ‘Hip Priest’) or issues terse and acerbic commentary on contemporary mores (from ‘British People In Hot Weather’ to ‘Hey! Student’), it’s those songs where his imagination is let off the leash that leave the more indelible imprint. And the fictions often fit a definable, unique pattern: Dickensian characters pitched in to almost-real-world horrors worthy of Edgar Allen Poe, M.R. James or H.P. Lovecraft. As such, ‘City Hobgoblins’, with its sprites and poltergeists meddling with the light switches in contemporary Manchester, are part of the thread that connects the paranoid protagonist of ‘A Figure Walks’ with the time-shifting hero of the blistering ‘Wings’, the mad kid of ‘Winter (Hostel-Maxi)’ and even some of the more possibly first-person-for-real stuff, like ‘Riddler’, where observable facts start to bleed into the murky background, where fears lurking in the shadows may be learning how to make themselves manifest. These two sides of his writing would go on to inform the group’s third studio album and give it a balance unique in the band’s sprawling discography.

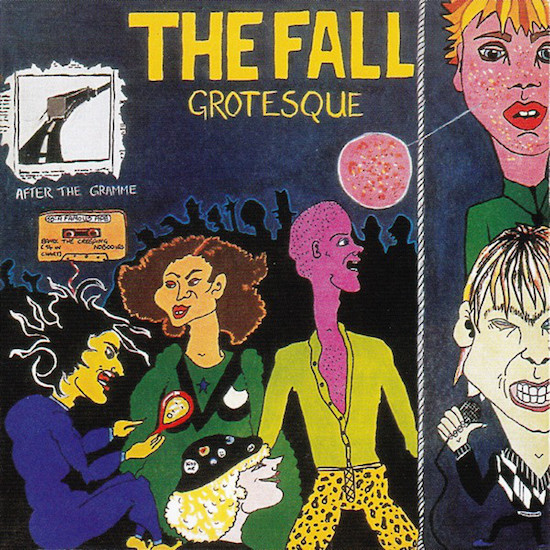

Grotesque (After The Gramme) arrived a month and a half before the end of the year, but only after another terrific single – ‘Totally Wired’, with its bricolage-around-a-song b-side ‘Putta Block’ – and what probably stands as the greatest of the band’s 24 Peel sessions. First broadcast towards the end of September, the third Fall Peel session featured four songs that would appear in other versions on three Fall LPs (‘Container Drivers’ and ‘New Face In Hell’ were already in the can for release on Grotesque; the version of ‘New Puritan’ is barely recognisable from the pause-tape edition that emerged on Totale’s Turns; and it would be another 18 months before ‘Jawbone And The Air Rifle’ got its definitive reading, as part of Hex Enduction Hour). It feels apt that ‘New Face’ and ‘Jawbone’ first saw the light of day at the same time: both belong to the sci-fi/horror section of Smith’s self-made library, and both feature enigmatic hunter characters. While researching this piece, I tried and failed to track down a passage I have a vivid memory of reading wherein someone with insight and/or imagination wonders whether ‘Jawbone’s "rabbit-killer" and the hunter that ‘New Face In Hell’s hero, "wireless enthusiast", discovers dead at his kitchen table may be one and the same person. The source eludes me; if it exists anywhere in the first place. Maybe one of Smith’s hobgoblins planted the seed in a dream.

The reason Grotesque works, and why it stands as a favourite album (if less often as the favourite) for many Fall fans, surely lies both in its blend of observation and imagination, and the sound of a line-up assured enough of its ongoing status to push themselves forward while still being new enough at playing (both individually and collectively) to not have had the rough edges knocked off their sound. Musically, it succeeds because its makers’ capabilities and limitations are in perfect equilibrium; lyrically, its principal author has a number of different styles and themes he wants to tackle and is similarly operating at that point right at the edge of experience where everything he tries is going to be just about doable but will require effort and a smidgeon of risk to pull it off.

Not everything works. ‘In The Park’, a rare foray for Smith into writing about the pleasures of the flesh, doesn’t convince and feels under-developed. For all that its flying-apart-at-the-seams performance keeps pace with its apparent intent to lampoon widescreen American road-travel hymning, ‘The Container Drivers’ leaves you with more of a sense of its fizz than its substance (and the Peel session version is better, in part because it’s a little bit cleaner and clearer). Opening track ‘Pay Your Rates’, too, may not be the greatest start, the performance a little lumpen in the uptempo passages, as wonderful and spacious as it is in the half-speed portions. But the rest of the record is an unalloyed triumph.

Even when the LP is at its least accessible and apparently its most inward-looking – the tape collage ‘WMC-Blob 59’, and the conventionally produced but deliberately strange tour diary ‘C "n" C-S Mithering’ – it’s properly captivating. It had already become a music-press cliche at the time that The Fall were an exercise in drawing attention to Smith’s inscrutable lyrics, with the punchline being that the more intrigued you found yourself when trying to decipher them, the harder the production and the sound would make that task; and, once such decoding was accomplished, the less likely one was to find whatever answers had been sought. Not for the last time, this conventional media narrative does little other than confirm that quite a few of those being paid to write about this stuff back then weren’t spending as much time or care on the listening-to-music part of the job as they were on the making-quips bit. It’s a trend that social media has surely only amplified since, but the result – readers and artists short-changed – remains the same.

On the other hand, who can blame them? There’s so much going on in Grotesque that it takes years of re-listening, and the collective efforts of the dedicated hive-mind components of the excellent Annotated Fall website, to even begin to identify some of the multitudes contained within the LP. Consider, for a moment, the closing epic, ‘The N.W.R.A.’, which begins with Smith relating a tale from a near-future where a heavily altered track from Grotesque is being played on a kids’ show on nationwide BBC radio, then sees him switch narrative perspective to inhabit the character of Joe Totale, "the yet unborn son" of a third character (Roman Totale XIII) who Smith had created to write press releases and sleeve notes for ‘Fiery Jack’ and Totale’s Turns ("I don’t particularly like the person singing on this L.P.. That said, I marvel at his guts") and in whose name he would occasionally sign letters he wrote in reply to fans. Or take a listen to ‘Impression Of J. Temperance’, where a song that appears to be about a dog-breeder turns out instead to be about his terrifying and (probably?) self-created simulacrum, discovered by a vet called Cameron who turns up to deliver the "new born thing hard to describe".

Where to begin? And at what point would you believe you’d finished figuring out what the hell was going on? Perhaps it’s better not to start, and just delight in how Smith uses his brilliant band like a stage conjuror uses the cape and top hat – as a diversion and a distraction, cloaking the deception. It’s little wonder contemporary critics baffled by Grotesque thought Smith was hiding something. In many ways they were right. The following year this line-up – with the brief addition of a clarinet player – made what is probably the best Fall LP (even though it’s not an LP; in fact, thinking about it, maybe because it’s not an LP), Slates, though it wouldn’t be until Brix’s arrival in 1984 that the group started to get widely talked about in the first rank of British music’s true greats, and their records began to achieve a level of commercial attainment that was commensurate with their artistic success. Anyone trying to critique and catalogue and contextualise this stuff as it came out was doomed to fail. It’s too deep, too densely packed, too rich in allusion and scope and too well-read and learned in its reference points, even in an era with so much more information so easily locatable as is the case in 21st-century internet-enabled present. Back in 1980, nobody really had a chance.

With a quick flap of some flabby wings, let’s fly to August 1984. The Fall have just released ‘c.r.e.e.p.’, their second single on Beggar’s Banquet, a poppy confection with recognisable and hummable hooks. Its initial 12" pressing is on green vinyl and is supposed to come with a print of the sleeve painting, the work of the artist Claus Castenskiold. Your correspondent’s copy is missing said print, and, following a suggestion published in one of the music weeklies (or possibly an announcement made by Peel – at 36 years’ distance one can hardly be sure, especially given I can’t even remember where I read about rabbit-killer and hunter this side of Christmas), a stamped-addressed envelope is fired off to an address in Manchester. Not wishing to waste the opportunity – and still at school (like Hanley had been in 1980, though it would be a long way down a different timeline before that fact slotted in to place) and some years from getting to interview musicians – I included a letter asking what must have felt at the time to be some pressing questions. One of those was clearly about what struck me at that point as the unfair irony that the same outlets that had given a fairly sniffy response not just to Grotesque but to ‘Elastic Man’ and ‘Totally Wired’ too were then – in 84 – busying themselves writing enthusiastic pieces about the new Fall releases, comparing them favourably with the 1980 vintage of the band, a supposed "return to form" after what had evidently – and entirely incorrectly – been considered the mis-step of Perverted By Language.

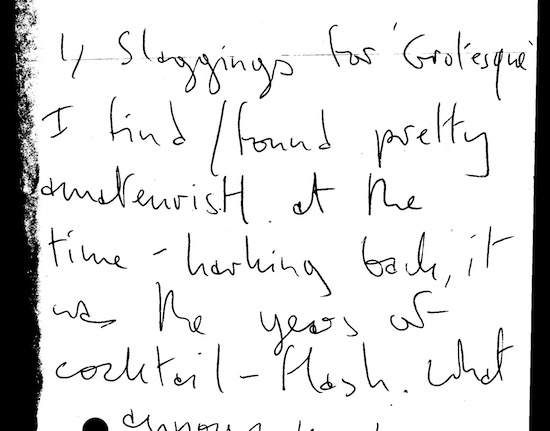

Just before Christmas the SAE turns up, containing a slightly torn and graffiti-ed print (down one side is scrawled "The Fall kiss your ass"), and a short note written in black biro on a torn half sheet of hole-punched A4. After explaining the condition of this last remaining copy of the print – "Karl abused it" – Smith turned to my questions. "Slaggings for Grotesque I find/found pretty amateurisH at the time," he wrote. "Harking back, it was the years of cocktail-flash. What annoys me more is the same jerks saying Perverted wasn’t as ‘excellent’ as Grotesque!" It was signed, "Happy Xmas etc! Mark + Brix." To say it remains a treasured possession is of course an inadequate understatement, but, as upset as I’d be to lose it to fire, flood or theft, the indomitable, unconquerable and entirely indestructible music is the true treasure here. Forty years on these records continue to give something more every time they’re played, their stature only growing as our distance from the moment of their creation increases. The Mighty Fall, indeed.